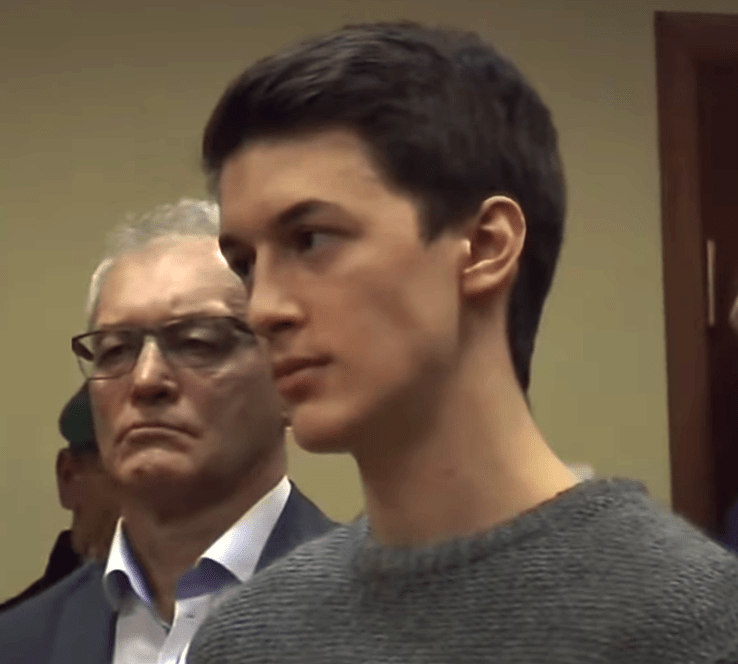

(PONARS Eurasia Commentary) On Sunday, August 30, Yegor Zhukov was beaten outside his home in Moscow. He is a 22-year-old recent bachelor’s degree graduate from Moscow’s Higher School of Economics (HSE) and is active in opposition politics.

His experience must have been difficult for his friends and supporters in the ill-omened context of the poisoning of Alexei Navalny, Russia’s most formidable opposition activist who is now in a coma. Russia watchers haven’t missed the attack on Zhukov as they watch Navalny’s condition.

No individual suspects were named in either attack. They likely won’t be as long as Russia’s officials signal that violence against the opposition is inconsequential. Additionally, the Zhukov case draws attention to the government’s politicization of Russia’s academic space, yet another sign of the power vertical’s reliance on repressive tools in 2020.

Free Thinkers

Zhukov is a Moscow native and symbol of “Generation P”—young Russians who do not remember a time before the rule of President Vladimir Putin. He became a rising star in Russia’s opposition community in July 2019 during the Moscow City Duma elections.

After election officials sidelined independent opposition candidates, Muscovites organized the largest peaceful protests since 2012. Zhukov attended, but was at the wrong place at the wrong time. While he was standing near a police barricade, officers pounced on him and later charged him with organizing unsanctioned demonstrations.

Jailed for a month and released on a suspended sentence, Zhukov developed a reputation as a possible “future president” of a free Russia. During his senior year as an undergraduate, he was featured in the media, on TV Rain and popular YouTube channel Redaktsia, and he became a radio host on Echo of Moscow coming face-to-face with leaders like Vladimir Zhirinovsky and Natalia Poklonskaya.

He had been attacked before, but this attack was more brutal. It reveals how the state (and its supporters on the street) considers intellectual dissent incompatible with the official brand of Russian patriotism. Violent repression against free thinkers is increasing as the state gives its silent approval for political violence as long as Navalny’s and Zhukov’s attackers remain free and invisible.

The attack adds insult-to-injury for Zhukov because the HSE, which is considered a prestigious and relatively liberal Russian university, tore up Zhukov’s letter of admission to his 2020 master’s degree program shortly after issuing it, apparently due to pressures “from above.”

HSE’s move is worrying. Besides coming four days before the start of the Russian school year, it could expose Zhukov to the military draft until he turns 27 or continues with his higher education. Such a tactic was already used in December 2019 to sideline Ruslan Shaveddinov, a project manager for Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, and send him to the Arctic. As the BBC wrote:

“Ruslan Shaveddinov was seized at his home in Moscow on Monday and flown 2,000 km (1,240 miles) to the remote Novaya Zemlya archipelago. Mr. Navalny accused the authorities of kidnapping the activist who, he said, was exempt from military service.”

This is only the latest instance of politicized higher education in Moscow. Meduza ran a story in January 2020 that HSE was “tightening the screws” and prohibiting “divisive” political activism. I heard that some HSE students’ school ID cards were deactivated because of social media posts that were critical of the government.

Choosing to Stay in Russia

Students of my age will be in their late thirties when Putin is supposed to leave office. The current politicization of academia is important for analysts who map scenarios of Russia’s political future and its educated elite. Zhukov’s “strategy” is an excellent case in point. Amid state repressions against him, the young activist could have transferred to a prestigious university in another country. He would have had good chances of being accepted at elite universities such as Yale or Stanford (where Navalny and his daughter studied, respectively).

However, Zhukov faced the Russian system head-on, in his hometown. When Alexey Pivovarov featured him on Redaktsia last year, Zhukov rejected any comparison to Alexander Solzhenitsyn or any other political prisoners who had to pay for their activism with their freedom. He wants to live in his home country and be active improving it.

Zhukov’s commitment to studying in Russia creates authenticity for him as a future political leader. It is a sign that winning respect from Russians is more important to him than winning it from the West, a departure from the “global citizen” archetype of a pro-Western opposition leader more comfortable in Washington than in Moscow. If he is unlucky and drafted into the army but lucky enough to complete his term of service in decent shape, his credibility will be even higher because a majority of Russians, similar to Americans, respect the armed forces as an institution.

Zhukov is serious about having a political future. In one of his video blogs in July 2019, he cleverly analyzes Mark Galeotti’s report on the Russian security forces. In another, he discusses Gene Sharp’s guide for creating peaceful transitions from dictatorship to democracy. In nearby Belarus, civil disobedience techniques are having some success undermining Alexander Lukashenko’s “brotherly” regime, suggesting that the methods advocated by those like Sharp and discussed by Zhukov could bring results to Russia, despite the strength of the siloviki.

The Kremlin sees how peaceful mass protests have put Lukashenko into a corner and may see harbingers of serious, sustained opposition in places like Khabarovsk and Kushtau. To Press Secretary Dmitry Peskov, however, Navalny is just a nameless patient who happens to be ill, amid popular uprisings, and before regional elections (where his Smart Vote initiative could very well threaten United Russia incumbents).

Peskov would likely say that the attack on Zhukov is just another coincidence. However, analysts of the Russian opposition should see it as an additional warning sign of potential violence against them, though not necessarily on Kremlin orders. The crimes against Navalny and Zhukov are, and will likely remain, anonymous, but they serve as evidence that the opposition poses a higher threat to the status quo now than it did before the constitutional plebiscite in late June 2020.

As of early September, there is no end in sight for community spread of COVID-19, unemployment, and social disruption. Yet as these pandemic conditions contribute to unrest, both Minsk and Moscow have neglected to provide economic aid and other “carrots” to quell the public’s discontent. Instead, increasingly desperate repressive measures are pulled from state toolboxes. Visit Okrestina jail in Minsk or Charite hospital in Berlin to learn more.

Alexander Naumov is a double B.A. candidate at George Mason University studying International Politics and Russian & Eurasian Studies. He lives in northern Virginia and is a native of Yoshkar-Ola, Russia.