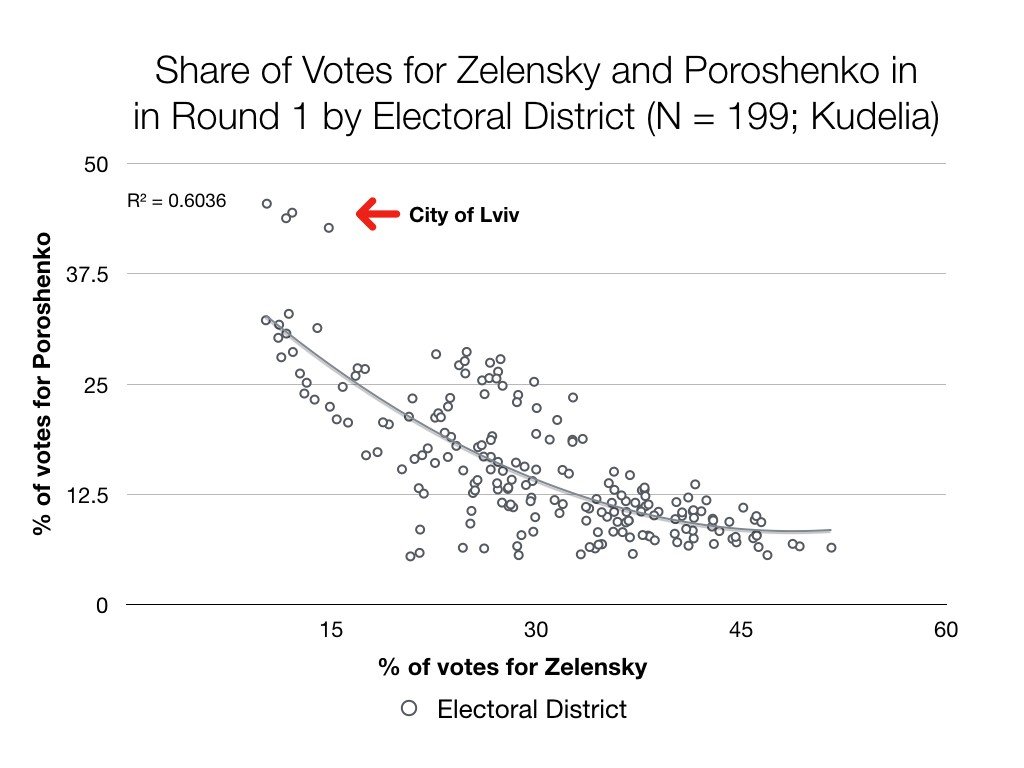

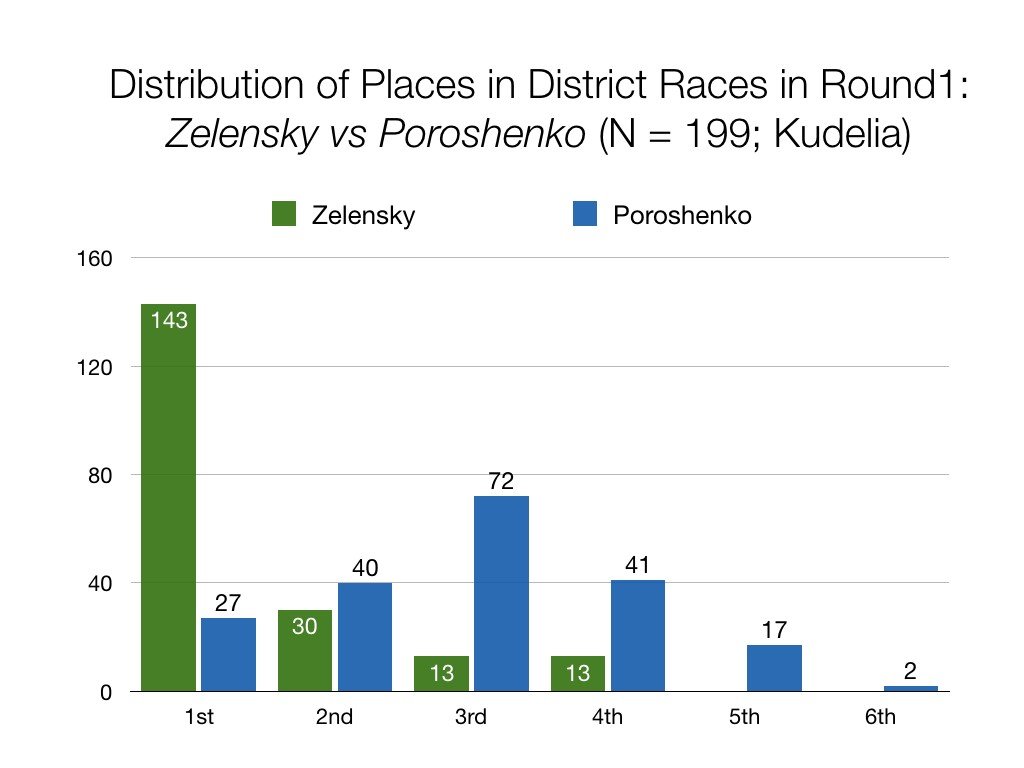

(PONARS Eurasia) The first round of the presidential election in Ukraine on March 31 produced two frontrunners who will face each other in the run-off on April 21: challenger Volodymyr Zelensky (30.24 percent) and incumbent Petro Poroshenko (15.95 percent). Only once, in 1994, did a candidate who lost in the first round of Ukraine’s presidential election go on to win the presidency. Then, however, the gap between the results of the first-placed and second-placed candidates was 7.2 percent, or half of what it is in the current election.

This is only one of several reasons why Ukraine may soon experience a fourth power turnover through an election in its democratic history.

While having a preponderance of financial and administrative resources and dominating television coverage, Poroshenko prevailed only in two oblasts of Western Ukraine (Lvivska and Ternopilska). His ideological platform stressing traditionalist values and ethnocentric policies resonated with a more conservative electorate, but could not gain a cross-regional appeal. Even in Halychyna, however, he gained, on average, merely a quarter of the total number of votes cast (26.6 percent).

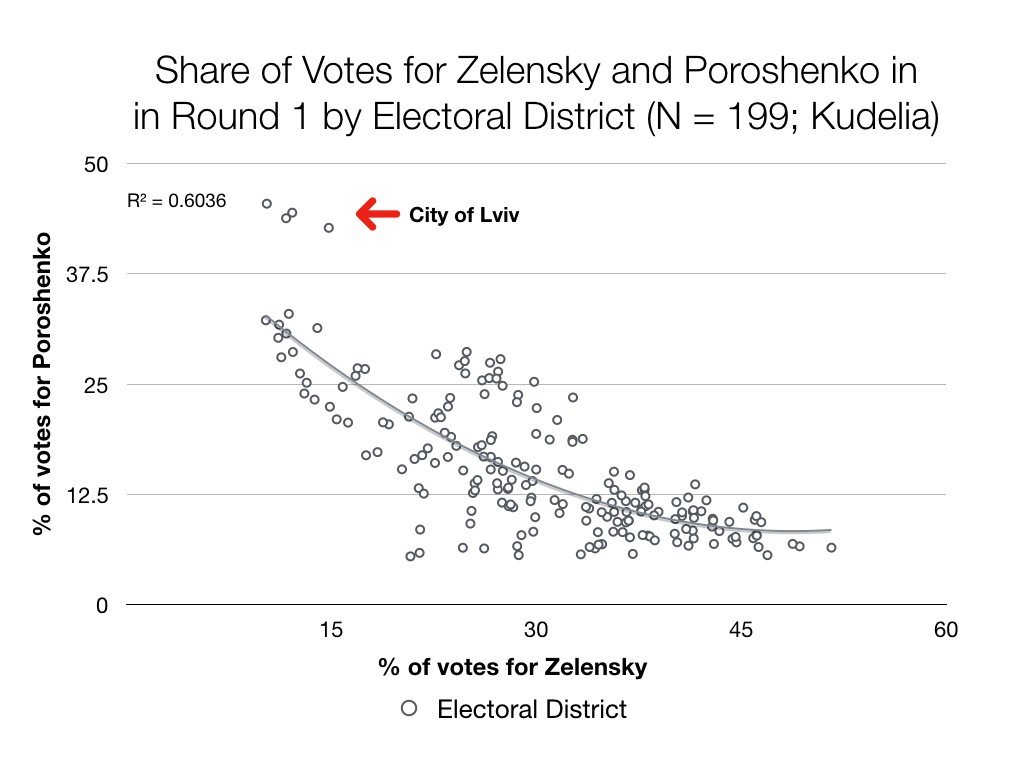

Poroshenko’s support exceeded 40 percent only in four electoral districts in the city of Lviv (see Figure 1). By contrast, Zelensky gained over 40 percent of the votes in three major Ukrainian provinces (Dnipropetrovsk, Odesa and Mykolaiv). He also benefitted from a substantial increase in turnout of younger voters, who constitute the most substantial of his electoral base. Every second voter in 18 to 29 age group according to Rating Group exit polls cast their ballots—an increase of 14 percent compared to 2014 election.

The incumbency became a major disadvantage for Poroshenko, just as it was for Viktor Yushchenko in the 2010 election, because of the record low level of trust in the authorities (9 percent) and record high number of people (over 2/3) disapproving of the general direction of the country after 2014 Euromaidan revolution. These conditions naturally privilege the opposition and lower entry costs for multiple challengers irrespective of their possible subpar quality or lack of prior experience. Higher than average turnout rates in some Eastern and Southern Ukrainian provinces also point to a greater mobilization of opposition voters in this election.

As Figure 1 shows, an increase in support for the political newcomer Zelensky was associated with the lower level of backing for the incumbent across 199 electoral districts. This suggests that his political newcomer status and an anti-establishment campaign became particularly attractive for those who sought to impose “electoral punishment” on the authorities. While winning in 19 out of 24 oblasts of Ukraine, Zelensky received the smallest share of votes of any frontrunner in Ukraine’s two-round presidential elections (see Figure 2). By contrast, the next seven candidates following Zelensky and Poroshenko received almost half of all votes in the election (49.27 percent).

This points to a highly fractured electorate desiring change, but lacking a clear consensus on the incumbent’s replacement. The fracturing of voters creates a potential for several coalition-building scenarios. However, Poroshenko’s clear ideological positioning before the first round and incumbency status narrows his possible path to victory in the remaining weeks.

Zelensky defeated Poroshenko in Eastern and Southern Ukraine by far greater margins than elsewhere indicating Poroshenko’s faint prospects of winning in any of these regions. Hence, the president’s only viable electoral strategy is in reassembling the “orange” coalition of 2004 centered on Central and Western Ukraine, which could give him a winning edge with a higher turnout in these areas.

His plan may be to politicize the geopolitical cleavage portraying his opponent as a pro-Russian stooge, which he already signaled in his appeal to hold public debates. This would be particularly difficult with regard to Zelensky who attracts a broad cross-section of younger voters (under 45) irrespective of their native language or region of residence. He received twice as many votes as Poroshenko in Chernivtsi oblast and three times as many in Zakarpattia – both in Western Ukraine. His advisors include several former government officials and members of parliament with strong pro-European credentials.

Poroshenko may also try to amplify his national security experience and risks associated with the power transfer to a neophyte politician. However, recent corruption allegations against his close circle related to defense procurement weaken Poroshenko’s credibility both as a reformer and as a commander-in-chief.

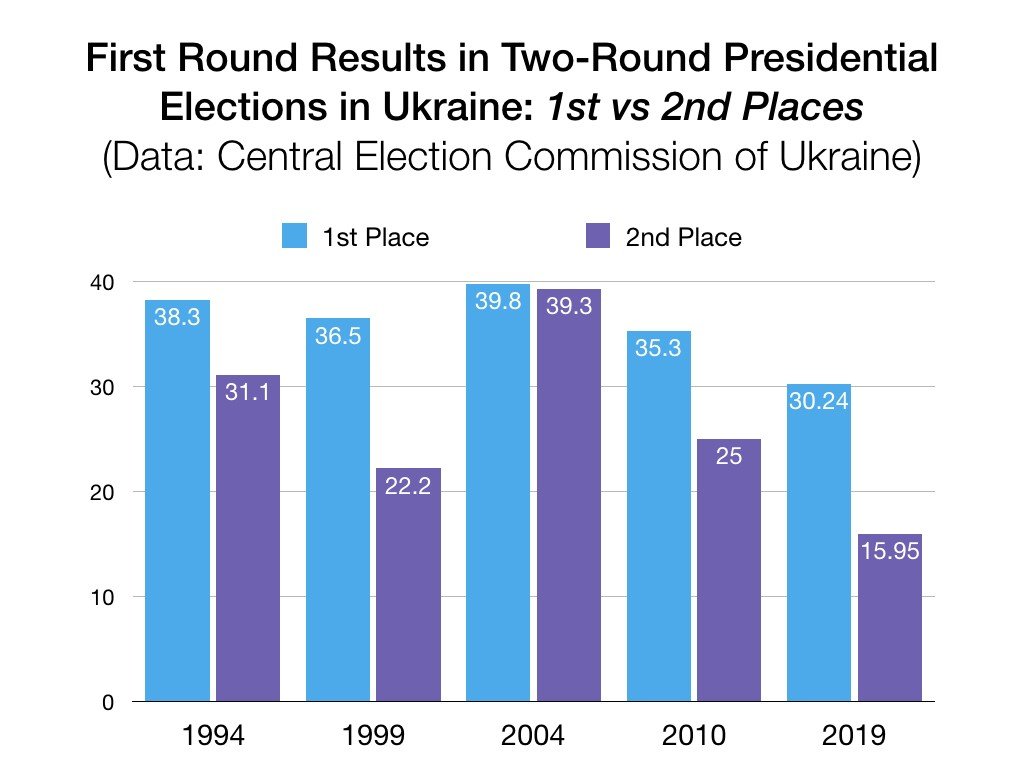

Poroshenko’s difficulty in catching up with Zelensky is also evident from his poor showing in many districts both in the East and the West of the country. Although he received the second place nationwide, he finished third or lower in 67 percent of electoral districts (see Figure 3).

This again points to a strong anti-incumbent preference among voters in this election. Other presidential candidates, like Yulia Tymoshenko, Yuriy Boiko, Anatoliy Hrytsenko and Ihor Smeshko, could play an important role in influencing voter choices in the second round. All of them already stated that they would refrain from aligning with any of the two candidates, but they dismissed the possibility of voting for Poroshenko.

This “negative” endorsement may essentially seal Poroshenko’s re-election prospects. It may produce a drop in turn-out in the regions crucial for his re-election and spontaneous coordination of more intensely opposition-minded voters around a new challenger.