“Let us regain the right to vote” rally in Moscow, August 10, 2019 (credit).

► Maria Lipman discusses the political developments of the past two months and the Russian government’s general policy toward elections with Mikhail Vinogradov, a Russian political expert and one of the most-often cited political commentators.

On Russia’s annual Election Day, Sunday, September 8, regional and municipal elections were held in dozens of Russian regions. The Moscow city legislature campaign attracted, by far, the most attention, and its outcome was indeed unexpected: the candidates supported by the powerful mayor’s office lost 20 seats out of 45. Five years ago, they lost just seven seats and secured an overwhelming majority.

Throughout Vladimir Putin’s leadership, the Kremlin has made sure that national and regional elections have pre-ordained results. Last year, however, brought about a few unpleasant surprises when Kremlin-selected gubernatorial candidates failed to win. Apparently, the Kremlin learnt its lessons and improved its operations: this year all of the gubernatorial races were won by Kremlin-approved incumbents or acting governors.

“Disobedience” continued in Moscow, however, where several prominent oppositionist figures tried to campaign for seats in the city legislature. But their attempts to break through Kremlin controls failed in a most egregious manner: all of them were barred from running. This demonstration of utter contempt for the Muscovites who supported the oppositionists or worked for their campaigns provoked mass protests that were brutally suppressed by the police.

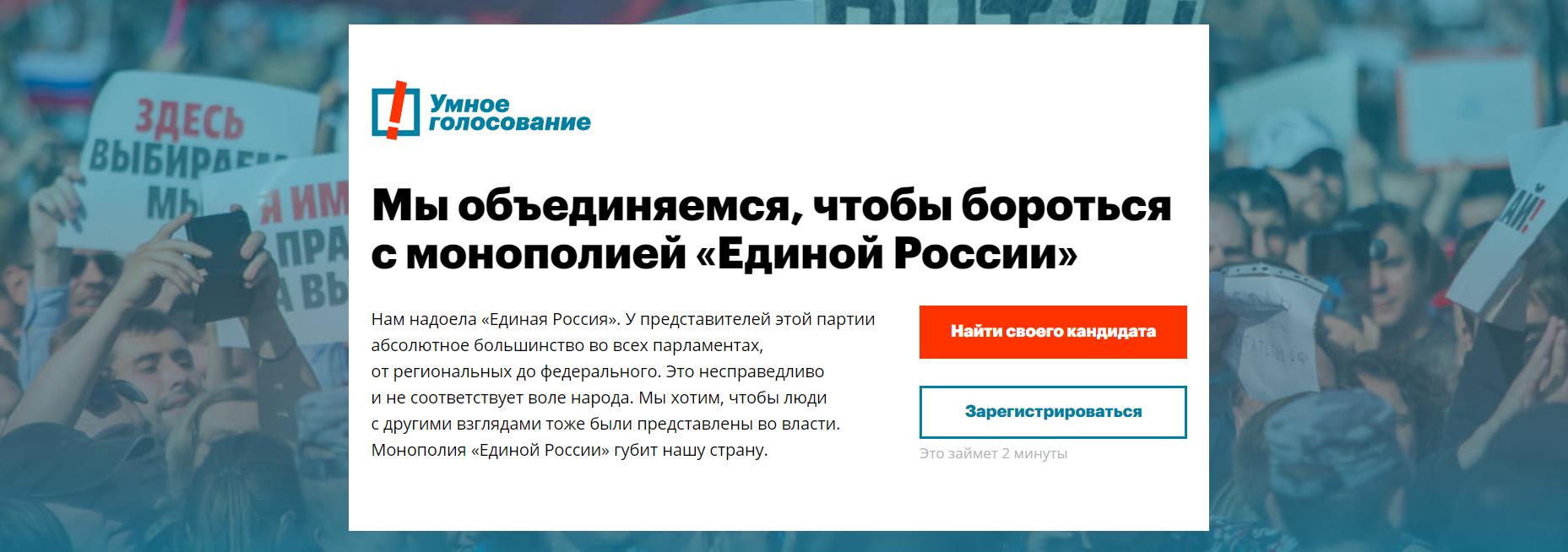

Stripped of the capacity to vote for the independent candidates of their choice, at least some of the opposition-minded Muscovites opted for “smart voting.” This tactic, suggested by the most prominent opposition figure, Aleksey Navalny, called Muscovites to vote for those on the ballots who, regardless of his or her political views or party affiliation, appeared to be the strongest opponent of the candidate supported by the mayor’s office. Most of the 20 winners who arguably owe their victory to this tactic are not likely choices for oppositionist-minded, liberal urbanites. They are members of “systemic” opposition parties (13 out of 20 are Communists) that are nominally opposed to the Kremlin, but in fact are generally tame. It remains to be seen just how their presence in the Moscow’s new city council, a body with a fairly limited discretion, will affect its operation. One thing is clear, however, the shameless barring of unwelcome candidates from the race and the brutal suppression of the ensuing street protests has worked to energize the opposition-minded Moscow constituency and undermine the effort of the powers-that-be to man the city council with their hand-picked candidates. –M. Lipman

Maria Lipman: What is your assessment of this year’s elections outcome? Are you surprised? What is the main reason for the defeat of the candidates supported by the Moscow mayor’s office—three times more seats in the city council were lost compared to the previous election?

Mikhail Vinogradov: I’d point out two things.

The first one is the unexpectedly high results of the pro-Kremlin gubernatorial candidates. The reasons are several. The government itself has not generated strong negative signals—unlike the announcement last year when a highly unpopular pension reform was announced just a few months before the annual election day. Gubernatorial challengers were thoroughly “filtered” and a strong effort aimed at increasing the turnout was taken on the election day. (When turnout grows as a result of administrative effort, this usually works to increase the incumbent vote.)

|

“Navalny’s suggestion, which was essentially to vote for the Communists on the ballot, was the most rational tactic, even though it was criticized by some within the opposition-minded constituency.”

|

The second thing is the effectiveness of “smart voting” in Moscow. Navalny’s suggestion, which was essentially to vote for the Communists on the ballot, was the most rational tactic, even though it was criticized by some within the opposition-minded constituency. Judging by the low turnout (a bit over 20 percent), not all the protest groups followed Navalny’s recommendations; some preferred not to come to the polls at all, but at least some effort was made to mobilize “smart voting.”

What was unexpected was that the administration’s traditional method of bringing to the precincts a sizable number of the government loyalists was not used to full efficiency. In many Moscow districts just a few hundred votes determined the election results, and in some they were in favor of the “smart voting” candidates. Also unexpected was the expansion of the “protest zone.” Traditional “protest zones” include central Moscow, its north-west and south-west, but this time a large eastern cluster, as well as individual districts in the north and south of the capital also joined the protest vote.

Today the question is whether the fairly tangible result achieved by the opposition will be followed by a demobilization of the protest movement (which appears more likely) or, the other way round, their electoral achievement will inspire a new wave of opposition activity. So far, the protest movement failed to develop a sense that their political self-fulfillment or even their electoral success is a strategic means, not an end in itself. Neither has this movement demonstrated a capacity to envision the government’s tactic: the oppositionists hardly make alternative plans for the case when, based on the current election results, the government may opt for a compromise, or take revenge on the opposition.

Screenshot of Navalny’s website page encouraging “smart voting.” The headline reads: “We are teaming up to fight the monopoly of United Russia.”

Lipman: How would you define the goals that the “власть” set for itself at the onset of the Moscow city council election campaign? (“Власть” means “the powers,” a term commonly used in Russia to refer to the government, political leadership or political establishment.)

Vinogradov: It is hard to talk about a generalized “власть,” even though experts like myself commonly use this term. It may probably be said that the main task was to prevent a merger of “power” and “politics.” Over the past years these two spaces have barely overlapped.

Lipman: What do you mean?

Vinogradov: In the 1990s and 2000s Russia had public politics, such as political talk shows or political parties. Today decision-making, such as allocation of budgetary funds, government appointments etc is virtually separate from the politics’ “public aspect.” Looking at this aspect one will not get the slightest idea of the government management operation or decision-making.

|

“The government’s goal was to conduct the campaign with minimal costs and to prevent any cleavages of the establishment… In other words, the goal was to carry out [the election] and forget about it.”

|

The government’s goal was to conduct the campaign with minimal costs and to prevent any cleavages of the establishment. The Moscow government sought to make sure that potential social turbulence would not be used to weaken the city authorities. In other words, the goal was to carry out [the election] and forget it. At last year’s Moscow mayoral election, [incumbent Sergey] Sobianin’s campaign had a more serious task: to let off steam, restyle the government management somewhat, and handle the “anti-rating” problem. But in 2019, such goals have not been set.

Lipman: Talking about minimal costs, is it fair to say that the government sought to ensure the vote for the desired or at least acceptable candidates and minimize the public resonance around the election?

Vinogradov: This may have been the ideal scenario: to keep the campaign quiet and reasonably unnoticed. This being said, the government did not get thoroughly prepared or examine the possibility of political maneuver.

The city authorities could have launched a campaign way ahead of the election aimed at smearing the oppositionists and municipal deputies. [Over 200 independent candidates were able to win in the Moscow municipal elections in 2017; the government did not interfere too much—apparently deeming those low-level and unpaid positions fairly unimportant. In the past two years, however, some of those municipal deputies were able to build loyal constituencies; they were among those who tried to run for the Moscow city council on September 8 and were barred from contesting the election. –M.L.]

After the 2017 local elections, the authorities could have spread the story that municipal deputies failed to achieve any success. Instead, they only remembered about those deputies at the time of the summer turbulence. [In June, prior to the city council campaign, an unlawful arrest of Ivan Golunov, an investigative journalist, caused mass protests in Moscow. Several dozen municipal deputies signed a letter to the Moscow law-enforcement demanding that Golunov be freed. –M.L.]

On the other hand, why bar some ten oppositionists from the race anyway? The Moscow city council is not a very influential body, not one that is often talked about. If elected they would indeed use their status to raise their public prominence, but this probably would have been an acceptable cost.

Opting for such tactic, however, would have implied an understanding that the societal divisions within Moscow are a political problem. Not a target of administrative manipulations and chaotic moves, but an essentially political issue—if politics is understood as a venue for settling the divisions existing between groups with different political preferences.

Lipman: Would you agree then that the costs turned out to be far from minimal? In fact, much more serious than the government wished…

|

“The administrators in Moscow, as well as in many other Russian regions, fail to understand that the government’s major ‘competitor’ is its own ‘anti-rating.’”

|

Vinogradov: The administrators in Moscow, as well as in many other Russian regions, fail to understand that the government’s major “competitor” is its own “anti-rating.” [In July, the rating of United Russia, the chief pro-Kremlin party dropped to about 32 percent, the lowest level in over a decade. –M.L.]

From a tactical perspective, the administrators of all levels have to work daily on preventing the anti-rating growth. But there’s also a more strategic, national aspect: the government should persuade the voter not to look at politics essentially as a venue of the battle between good and evil. As long as this vision persists and the government does not debunk it, a range of idealists gravitate toward the political realm. It would make more sense for the government to reformat the realm of political power so it would be service-oriented. At this point the government managers fail to realize that this is a vital need, but such as reformatting is not impossible. The government should get rid of the illusion that the public would perceive the powers that be as a force for good. In fact, the people increasingly tend not to associate the government, “власть” with good.

Lipman: So do you mean that the government should position itself as a service structure? But the situation with services in Moscow is not bad at all…

Vinogradov: Politically, this aspect of the government performance has been “undersold” as it were, both at the Moscow level and the national one. In Russia there is a common perception shared by both, the loyalists and the oppositions—a yearning to think of oneself as a force for good. This is an important element of the protest movement, as well as of many loyalists’ perception. But “власть” would benefit from abandoning this realm; this way it would avoid radical public disappointment. I have the impression that when people look at various improvements, such as beautification, etc., they think, “it’s fine, but this is your duty, what you owe us anyway.” This attitude does not convert into a rise in public support.

Lipman: So in Moscow the government turned out to be underprepared for the city council elections. Would you say they also made mistakes later, during the campaign, when it became clear that things were not evolving in the desired direction—I mean when mass protests erupted?

|

“The government critics currently lack the power or will to generate a new wave of protest pressure… Another problem faced by the opposition is the absence of their own agenda.”

|

Vinogradov: I would not treat the events of July-August as a series of mistakes. On the whole the government managed, if partially, to solve the main problem: to prevent mass rallies from converting into something of a larger scale. The protest movement did not escalate. The composition of the new city council is not such that the government would be unable to manage it. The government critics currently lack the power or will to generate a new wave of protest pressure. At this point, those who poured out their passions by joining the protest rallies in July and August seem to feel reasonably satisfied. Another problem faced by the opposition is the absence of their own agenda. I don’t mean it as criticism, but it can be seen that public mobilization occurs only around the agenda set by “власть.” The protest’s success depends on the temperature existing in the society, but while the protest contributes to this temperature, the temperature itself is not generated exclusively by the protest sentiments. I would point out the statement made by Chemezov—apparently he, too, could not stay silent. This is where key risks lie—this was the case in 2011, as well as today. [After the brutal suppression of protest rallies, Sergey Chemezov, CEO of a state-owned industrial conglomerate and powerful member of the establishment, unexpectedly spoke in support of “a sound opposition.” “It’s obvious, people are very upset,” he said, “and that’s not good for anyone.” –M.L.]

Lipman: According to proekt.media, secret polls commissioned by the government showed that about nine oppositionists had a good chance of winning and that was what drove the government to bar them from running. Do you really believe that the government could have afforded to let about a dozen opposition figures onto the Moscow city council?

Vinogradov: The establishment’s dominant perception is that political power cannot be divided. You either have it or you don’t. Political experts may look at it differently: in their view political power is an instrument of settling divisions of various intensity that emerge in society. As many as nine independent deputies in the city council could have been “integrated.” Three would probably have been corrupted and incorporated into the system, and the others would have fallen out with each other; as a result, they would not have formed a group, but would have operated as individuals—this was what happened earlier in the St. Petersburg legislature. The government has enough tools to mitigate any potential opposition activity in the Moscow city council. Of course, those in the administration who are in charge of managing elections may be concerned that if they let in opposition figures, their rivals in the establishment might regard this as their failure and take advantage of it. But such rivalry is a reality they deal with; whatever you do, somebody will always try to interpret it as a failure. The question is whose view is more accurate: the experts may have a correct understanding, but they are not immediately involved in decision-making. For the power-holders who regard political power as indivisible, there may be only one major goal: to retain that power.

Police detain a man in Moscow at a rally for fair elections, August 2019 (credit).

Lipman: During the protests that followed the disqualification of unwanted candidates police brutality alternated with spells of softer policy. This led some observers to suggest that there were two “parties” involved in decision-making: “the civilians” and “the uniformed,” the siloviki. Another theory had it that it was always the same hand that was simply pressing different buttons. How do you see it?

Vinogradov: I’d rather challenge the conventional thinking. I have a sense that in general the process evolves by itself, with “власть” interfering only sometimes. The government may be able to influence the process every once in a while, but this is an influence on a process that evolves by itself. This model has its strengths and weaknesses, its risks and hopes. In short, everything evolves by itself; the number of developments is virtually countless, and the government has only a limited capacity to respond.

Lipman: In your picture, is there a top manager who gives orders and decides which agency should interfere and respond to the developments?

|

“Pretending that nothing is going on is an important element of the Russian power rituals; political officials commonly resort to this ‘tool’ in response to the general process that evolves by itself.”

|

Vinogradov: In the political configuration that has evolved since 2014, everything converges to a single center, but that central authority interferes only occasionally and keeps a distance between the public agenda and his own moves. This pattern has been adopted by a broad range of managing figures. Here’s an example: when the Moscow State University rector made a statement regarding his school’s students’ behavior during protest rallies he sounded moderate and generally respectful. But when he was asked about Yegor Zhukov, he pretended that he knew nothing about it. [Zhukov, a student at the Higher School of Economics, was arrested at the height of the Moscow protests; many students stood up in his defense. –M.L.] Pretending that nothing is going on is an important element of the Russian power rituals; political officials commonly resort to this “tool” in response to the general process that evolves by itself.

Lipman: Some of your colleagues, as well as many among the media commentators and protesters themselves, offer the following interpretation of the developments of July and August: the protests against the removal of the unwelcome candidates from the race took the government by surprise. The “civilian” segment of the establishment, that is those who prefer manipulations to police brutalities, failed to cope with it. Then the other segment, the siloviki, who are in favor of beatings and detentions came to the supreme government authority and said: they have failed, let us try now. Is this picture incorrect?

Vinogradov: It is an illusion that when siloviki are entrusted with a mission, they seek to grab all the authority and not return it to anybody. When they find themselves in charge vis-à-vis chaotic developments and not infrequently in the absence of explicit commands, they act as they see fit, and, by the way, not all the siloviki have the same ideas of how to act.

I think it is noteworthy that the head of Rosgvardia [Russian National Guard] Viktor Zolotov said in an interview that Putin “will never give an order to shoot at people.” It was clear that this line was psychologically important for him and he proceeded from the assumption that this could not happen.

|

“In dealing with protest rallies law-enforcers pursue two major goals: not to be held ultimately responsible and to prevent fraternization between the police and the protesters.”

|

I believe that in dealing with protest rallies law-enforcers pursue two major goals: not to be held ultimately responsible and to prevent fraternization between the police and the protesters.

In the case of the current protests I think it was the general inertia that helped mitigate the situation, not the succession of the government’s decisions whether good or bad.

Lipman: In one of your recent Facebook posts you wrote that “the opposition’s strength lies in the sometimes irrational moves of the establishment.” Does this mean that for all the weakness of the opposition that you discussed earlier, it also has a strength that enables it to have some impact on the political process?

Vinogradov: This strength has to do with the fact that the political space in post-Soviet Russia, and, to various extents, also in other periods of the Russian history, has never been conceived as a venue for settling differences among various social, public, ideological groups, various lobbying forces, etc. There is no sense here that this is what politics was invented for in the first place. As a result, the differences and contradictions remain under the surface and this is what endows the opposition with some strength. This strength derives from unarticulated tensions, from the gap between the Muscovites’ perception of their city as a leading European and global megalopolis with a population twice as large as Switzerland’s—and the Moscow’s outgoing city legislature whose composition by far does not reflect the rising complexity of the Moscow constituency.

In recent years the establishment has displayed a preference for simplification, so all the complex developments would be explained by just one factor. This scheme is tempting from the point of view of the political tactics, but it fails to manage the risks. And the establishment’s failure to understand that risk-management is an important instrument of the retention of power leads to a social turbulence. The protest movement benefits from the government’s reluctance to understand the complexity of the society. Although this movement is essentially weak and lacks a general strategy, it is fueled by this energy of unresolved and unarticulated contradictions.

Lipman: One last question. In one of your Facebook posts you wrote that the government is losing the monopoly on patriotism. What did you mean by that?

|

“Young Russians do not share the assumption common among older generations that Russia is inferior to the West because its realities do not match Western or American ones.”

|

Vinogradov: This was just a hypothesis. Thanks to improved living conditions in beautified urban centers with their shopping malls, bike lanes, cafes, etc. young people—unlike the generations of those in their 40s and 50s—no longer regard Russia as a catching-up country or one that is going through economic and political transition. For them Russia is not a world’s periphery or province, it is its integral part, even if they do not specially reflect on that. They do not share the assumption common among older generations that Russia is inferior to the West because its realities do not match Western or American ones.

The reason for that may be that when they were growing up the West was no longer the reference point it had been for the 1980s generation—a political and consumption paradise, as it were. In many aspects that gap has narrowed, and, as a result, the political leadership may be losing the monopoly on patriotism. This is one of the reasons why it seems important that the government should abandon the realm of Good and Evil.

Lipman: The often heard observation that “Russians under 25 know nothing but Putin” sounds a bit paradoxical: it implies that their political experience is limited to an authoritarian order, yet they have not become suppressed or submissive.

Vinogradov: In a sense, they have not seen Putin either! They have only seen him as a symbol, rather than a political actor.

Lipman: Today’s young Russians enjoy considerable freedom in those spheres that are most important to them. In Russia, as elsewhere, this is a generation that lives in large part “in their phones,” and phones are fully accessible. They can watch and listen to whatever they like; they are free to pursue lifestyles of their choice. They have virtually unlimited access to these things and they can generally afford their desired lifestyle.

Vinogradov: This is why an interest in politics is by far not a given for this group, but politicization may occur as a reaction to a sense of want of historical dynamics.

Mikhail Vinogradov is the president of the “St. Petersburg Politics” foundation, one of Russia’s top think tanks.