Thomas Piketty, a French economist specializing in wealth and income disparity trends, stated his view quite clearly in his 2014 book, Capital in the 21st Century. Whether we like it or not, his claim is that rising inequality is going to be a long-term trend, and this poses a threat to the global democratic order.

The book is certainly a great piece of work by an academic economist. But is it, as The Barnes and Noble Review wrote, “Karl Marx’s true legacy?" I briefly look at Piketty’s argument on the income equality debate (see my previous posts on the topic here and here).

In Piketty's view, inequality is a long-term trend caused by an increase in the wealth-to-output ratio (capital-to-K/Y), leading to a rise in the share of capital in national income (“patrimonial capitalism”). One immediate critique, as raised by Milanovic (2014), is that it is not clear if an increase in capital versus labor would cause a decline in the rate of profit to counterbalance the growth of capital. (Economists believe that capital productivity declines if more and more capital is invested without a proportional increase in labor.)

Nonetheless, even with a stable capital to output ratio, an increase in inequality in a perfectly competitive market seems to be quite inevitable. Conventional wisdom still holds that competitive capitalism left to itself without any government regulation can ensure a fair and stable distribution of income and an "optimal degree of inequality." All agents, including the owners of labor, capital, land, and intellectual property, get remuneration equal to their marginal productivity, which thus leads to social harmony. This way of thinking also maintains that only market imperfections, such as credit constraints and lack of access to education, can result in “unreasonable inequalities.” In his book, Piketty questions such conventional thinking.

Many well-known economists, such as Stiglitz, have taken a similar position. But Piketty provides meticulous and extensive evidence that the reduction of inequality for the majority of the population in the 20th century leading up to the 1980s was only a temporary deviation from the overall trend and was caused by very special circumstances that are not likely to be repeated in the future.

Long-Term Inequality Trends

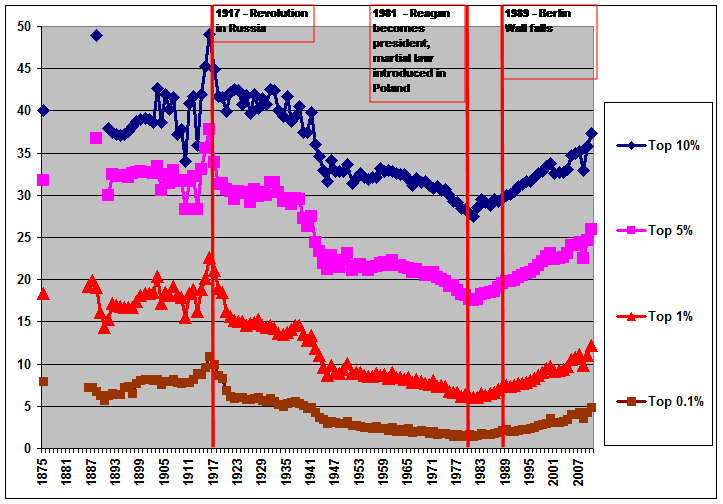

The long-term dynamics of inequality seem to be such that inequality increased between 1500 and 1900, probably reaching an all-time peak in the early 20th century (see Table 1 and Figures. 1, 2, 3) and only started to decline following the WWI and the 1917 Russian Revolution.

Table 1. Gini coefficients around particular years in Western countries, %

|

Years

|

14

|

1000

|

1290

|

1550

|

1700

|

1750

|

1800

|

2000

|

|

Rome

|

39

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Byzantine

|

|

41

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Holland

|

|

|

|

56

|

|

63

|

57

|

30.9

|

|

England

|

|

|

36.7

|

|

55.6

|

52.2

|

59.3

|

37.4

|

|

Old Castille/Spain

|

|

|

|

|

|

52.5

|

|

34.7

|

|

Kingdom of Naples/Italy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

28.1

|

35.9

|

|

France

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

55

|

33

|

Source: Milanovic, Lindert, Williamson, 2007; Modalsli, 2013; data for 2000 are sometimes from the World Development Indicators database.

An increase in income inequality accompanied the destruction of communal and collectivist institutions, something that was first carried out in Western countries between the 16th and 19th centuries.

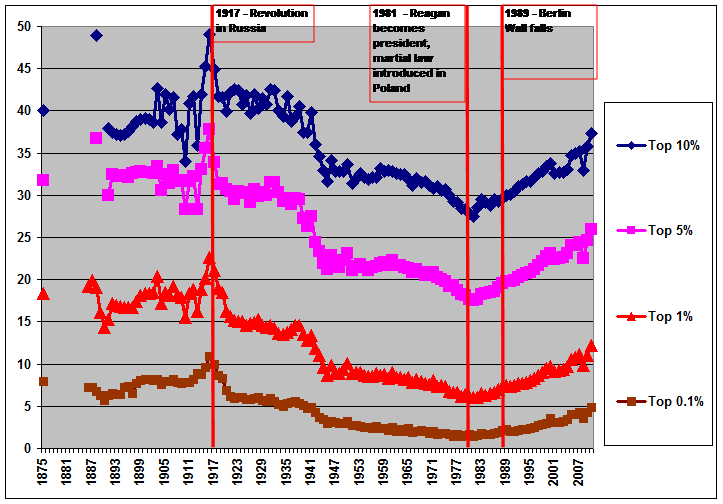

As seen in Table 1, for England, Holland, and Spain in the 18th century, the Gini coefficient of income distribution was at a level of 50 and even 60 percent—an extremely high level according to today’s standards and also according to the standards of the distant past. In England and Wales, the Gini coefficient increased from 46 percent in 1688 to 53 percent in the 1860s (Saito, 2009). In Denmark, a country with well-maintained records on individual incomes, the share of the top 10 percent in total income from 1870-1920 was always over 40 percent (reaching 54 percent in 1917), whereas the Gini coefficient for this period was always higher than 40 percent, exceeding an unprecedented 70 percent in 1917 (Atkinson, Søgaard 2013).

Figure 1. Income shares of top 0.1, 1, 5, and 10% in 17 developed countries (unweighted average)

Note: Chart contains unweighted averages for Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the United States. These are the data on pre-tax income derived from tax returns. There are some discrepancies between the two, but the data from household surveys for more recent periods show similar time trends, although inequalities in income after taxes are generally lower than before taxes. Source: Alvaredo, Facundo, Anthony B. Atkinson, Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, The World Top Incomes Database, April 25, 2012.

Data for the UK and the United States based on the reconstruction of the social tables for the pre-modern period provide a similar picture, mainly an increase in inequality before the 1860s and a decline in the middle of the 20th Century. (See Figure 2. Comparable data from 1867-1929 are missing.)

Figure 2. Inequality in the US and UK over the long run, Gini coefficient, %

Source: Ginis are computed by B. Milanovic from social tables before the 20th century and from household survey and tax returns afterwards (Milanovic 2013; Milanovic, Lindert, Williamson 2007; and personal correspondence with B. Milanovic).

In the United States, income and wealth inequality in the late 18th century was likely lower than in Europe due to the absence of large accumulated fortunes in the New World and the abundance of free land. In the late 18th century, the top 10 percent of wealth holders accounted for only 45 percent of total wealth in the U.S. as compared to 64 percent in Scotland and 46-80 percent in Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark (Soltow, 1989, 238). But it appears that inequality increased greatly in the 19th and early-20th centuries, reaching a peak in the interwar period (Soltow 1989, 251).

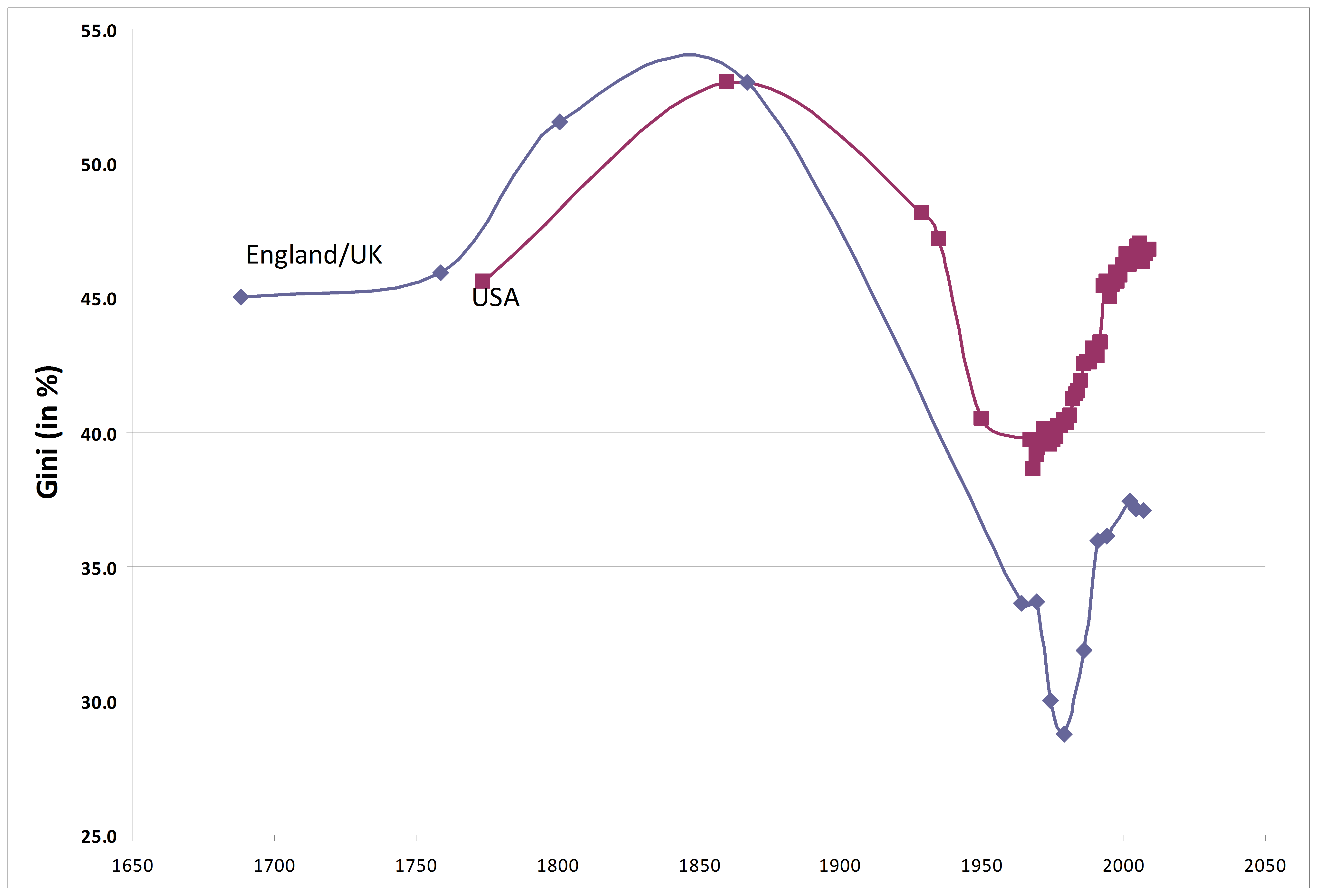

The data show some decrease in income inequality during the first half of the 19th century in the US and no noticeable increase in the wealth inequality in the same period, but the ratio of the largest fortunes to the median wealth of households (Phillips, 2002) tells a different story (See Figure 3). This ratio increased from 1000 in 1790 to 1,250,000 in 1912 (e.g., Elias Derby’s $1million compared to John D. Rockefellers’s $1billion). It then fell to 60,000 in 1982 (e.g., Daniel Ludwig "only" had $2billion) but then increased to 1,416, 000 in 1999 (think of the $85billion fortune of Bill Gates). Turchin (2013) regards these dynamics as “repeated back-and-forth swings” and thinks that the decline in inequality after 1917 was associated with the rise of the workers movement in the United States and “the lure of Bolshevism.”

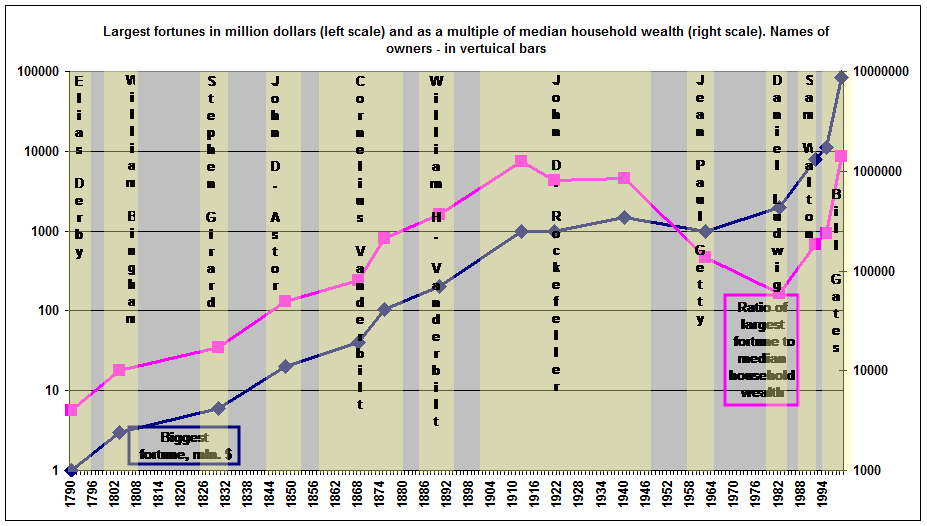

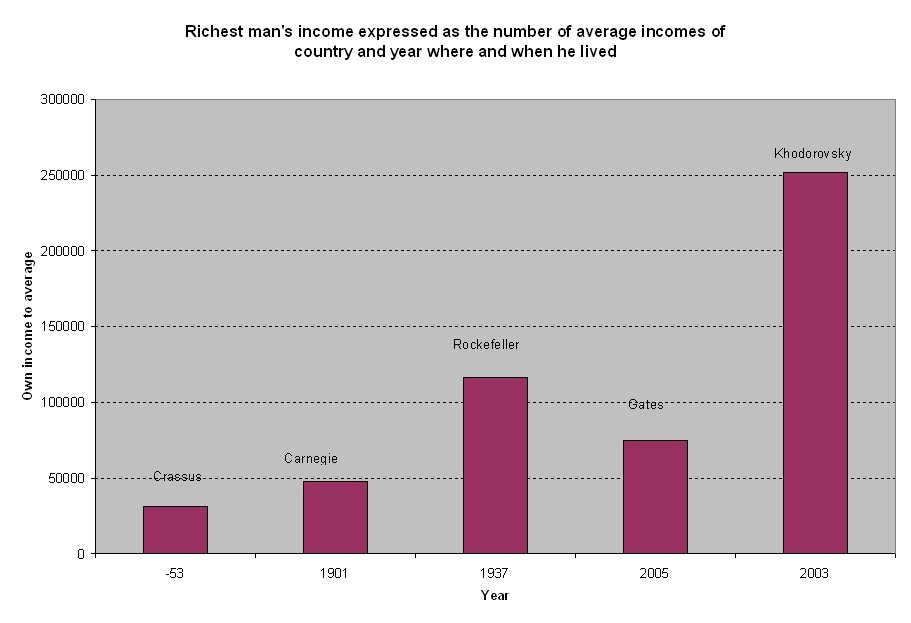

The wealth comparison of the richest tycoons (See Figure 4) gives different numbers, as it relates to average income and not to average household wealth, but basically draws the same conclusions. Bill Gates was relatively (as compared to the average income levels in the United States) poorer than Rockefeller, but richer than Carnegie and Crassus, whereas Russian tycoon Michail Khodorkovsky in 2003 was relatively (as compared to the average income in Russia) richer than all of them. The world may not have reached the highest point of inequality yet, but may be moving in that direction.

Figure 3. Largest fortunes in the United States in millions of dollars and as a multiple of the median wealth of households, log scale

Source: Phillips 2002, p. 38.

Figure 4.

Source: Milanovic 2011.

Whither Income Inequality?

As mentioned, only in the 20th century was the trend of an increase in income and wealth inequality temporarily interrupted, most likely, because of the checks and balances that socialist countries with low levels of inequality provided for the capitalist system (See Figure 1). A troubling trend since the 1980s has been the new rise in income and wealth inequality in the West and many developing countries (Jomo, Popov, 2013). According to Piketty, the period of 1914-73 was an exception in capitalist development due to two world wars and the Great Depression resulting in the destruction of capital and the institution of strong social policies during the New Deal in the United States and in Europe after WWII. This is certainly part of the story but not all of it. Strong social policies and the declining inequality of the post-war period are due not only to the threatening events which surrounded them, but also to the existence of a viable alternative to capitalism in the form of global socialism.

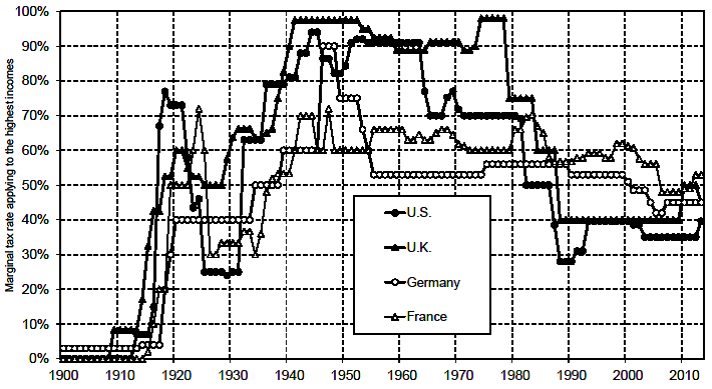

In a similar vein, today there is a more immediate reason for the possible continuation of an increase in inequality: the elimination of checks and balances that global socialism provided to capitalism. It became clear in the 1970s that socialism was not catching up to capitalism and that it was no longer an appealing alternative (see my previous posts here and here). The wave of neo-conservatism led by Margaret Thatcher in Great Britain and Ronald Reagan in the United States with its harsh policies toward workers’ movements was a capitalist response to the new social configuration. Government spending, including on social programs, stopped growing, many welfare programs were curtailed, unemployment rose to a fifty-year high, and trade unions' membership started to decline. Income tax rates for the wealthiest, which had always been higher than 50 percent in the United States, UK, Germany, and France between 1940-80 (and sometimes even as high as 90 percent) had dropped to below 50 percent by 2010 (See Figure 5). It should come as no surprise that income and wealth inequality began to rise in most countries during this time (See Figures 1-3).

There are other factors of course that influence inequality trends. For example, CEOs and top managers, as Piketty notes,a re not rewarded according to their marginal productivity, but rather by agreements between themselves and the owners.

Figure 5. Top income tax rates in the US, UK, Germany and France in 1900-2010, %

Source: Technical appendix of the book, Capital in the 21st Century, by Thomas Piketty, Harvard University Press, March 2014

Piketty's book reached number one on The New York Times bestseller nonfiction list, which does not happen frequently to works by economists. In its review, The Washington Post said, “In its magisterial sweep and ambition, Piketty’s latest work, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, is clearly modeled after Marx’s Das Kapital. But where Marx’s research was spotty, Piketty’s is prodigious.” It may not be magisterial, but certainly at the very least, a work like this can lead to new ideas from other economists, perhaps new ideas on how to stem income inequality trends and, as Piketty foresees, preventing the capitalist system from one day imploding due because of itself.

*****

References

Alvaredo, Facundo, Anthony B. Atkinson, Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez (2012). The World Top Incomes Database, April 25, 2012.

Atkinson, A.B., J. E. Søgaard, "The long-run history of income inequality in Denmark: Top incomes from 1870 to 2010," EPRU Working Paper Series 2013-01, Economic Policy Research Unit Department of Economics University of Copenhagen, 2013.

Jomo, K.S., V. Popov, "Whither Income Inequalities?" MPRA Paper No. 52154, December 2013.

Milanovic, B., The Haves and Have-Nots. A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality, Basic Books, New York, 2011.

Milanovic, B., "The return of “patrimonial capitalism”: review of Thomas Piketty's Capital in the 21st century," Journal of Economic Literature, June 2014.

Milanovic, Branko, Peter H. Lindert, Jeffrey G. Williamson, "Measuring Ancient Inequality," World Bank Policy Research working paper no. WPS 4412, 2007 (published as: Pre-Industrial Inequality,The Economic Journal, 2010).

Phillips, Kevin. Wealth and Democracy: A Political History of the American Rich, Broadway Books, NY, 2002.

Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belknap Press, 2014. (Many related links about the book can be found here at the Harvard University Press website.)

Saito, O., "Income Growth and Inequality Over the Very Long Run: England, India and Japan Compared," paper presented at The First International Symposium of Comparative Research on Major Regional Powers in Eurasia, July 10, 2009.

Soltow, Lee. Distribution of Wealth and Income in the United States in 1798. University of Pittsburg Press, Pittsburg, 1989.

Turchin, Peter., "Return of the oppressed," AEON, February 2013.