Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has unsettled Central Asia. The governments of these republics have distanced themselves from the Kremlin’s military affairs and sought to diversify their diplomatic, security, and economic relations. The uncoupling of these republics’ economic and military ties with Moscow seemed to portend the gradual demise of Russia’s regional projects: the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Instead of disappearing into the abyss of irrelevance, however, the EEU framework has supported a flurry of economic activity and energy deals in the region. The security and political benefits of the CSTO, meanwhile, have so far remained compelling for the organization’s Central Asian members.

The tenacity of “integration” projects in Central Asia defies traditional institutionalist or realist explanations. These initiatives have failed to deepen regional economic integration and mutual collective defense, and Russia no longer wields the kind of decisive economic and political influence that would support them. I argue these institutions are best understood as risk and opportunity management projects that benefit ruling elites. If the Kremlin has been able to take short-term advantage of the EEU to circumvent Western sanctions and export control measures, other EEU governments have profited from taking in business ventures that have exited Russia and Belarus, the influx of revenue from parallel trade with Moscow, and their position as transit hubs. Meanwhile, membership in the CSTO offers weapons transfers and anti-terrorism training that help the regimes stay in power. So long as the Russian and Central Asian governments can repurpose the relationships, processes, and rules of these organizations for their own political and economic aims, these projects are likely to persist.

The Eurasian Economic Union: A Cog in Geoeconomic and Geopolitical Schemes

The EEU, comprised of Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan (with Moldova, Uzbekistan, and Cuba holding observer status), faced serious challenges from the start. Rolled out in 2015, the project of regional economic integration and cooperation soon saw a significant decline in trade turnover among its members. Russia’s economic crisis, precipitated by Western sanctions in the wake of Moscow’s illegal annexation of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine’s Donbas, coupled with plummeting crude oil prices, had detrimental downstream effects on EEU members’ economies. In the years that have followed, the various protectionist measures and artificial barriers to trade adopted by the EEU states, along with tariff rate quotas that disproportionately benefit Russia, have derailed the fulfillment of the free trade agreement. As a consequence, intra-EEU trade accounted for less than 15 percent of the total trade volume of the Union’s members in 2021, in contrast to intra-European Union trade, which accounted for more than 60 percent of its members’ total trade.

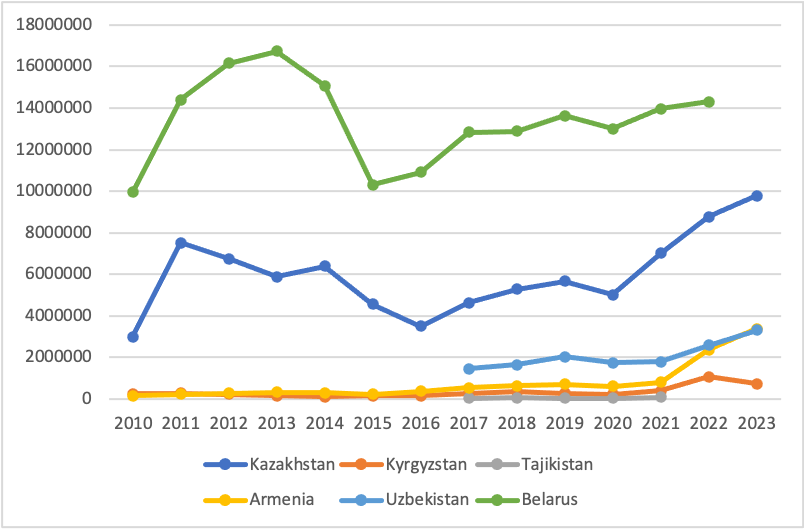

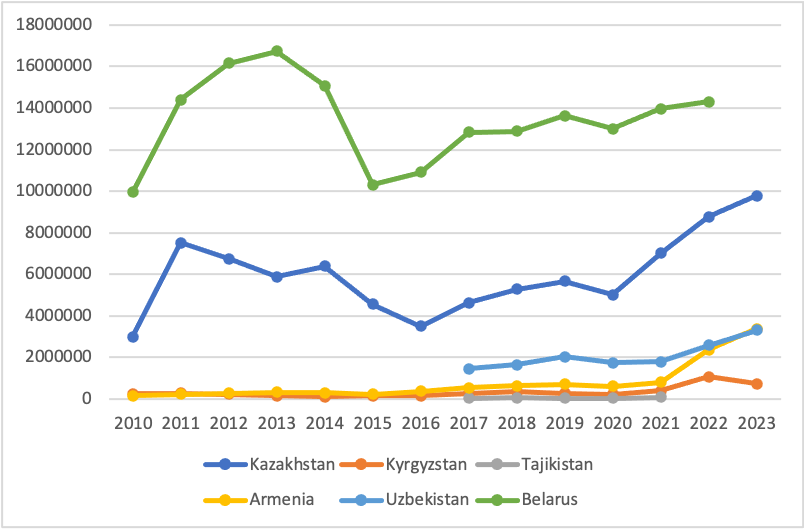

The unprecedented economic sanctions imposed on Russia in the wake of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine have further disrupted the EEU members’ trade and financial relations with Moscow. That being said, the war and sanctions have also created new commercial incentives and opportunities within the Union’s structures. With the exceptions of sanctioned Russia and Belarus, the economies of EEU member-states uniformly expanded in 2022, with growth rates ranging from 3.2 percent in Kazakhstan to 12.6 percent in Armenia. All EEU members, as well as Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, saw economic growth in 2023 (see Figure 1). Many factors were at play here, including China’s reopening after the pandemic and the relocation of Western and Russian businesses to Moscow’s neighbors. The EEU, which had previously been a clunky mode of facilitating trade among the Union’s members, also offered simplified cross-border rules and practices that proved to be highly adaptive to the threat of secondary sanctions, allowing its members to trade with Russia in sanctioned and restricted goods. The EEU countries’ exports to Russia grew in 2022 and 2023 (see Figure 2), with exports of certain articles—electronics, mobile phones, cars and luxury goods, nuclear reactors, and even drones—seeing massive increases despite the fact that no local industries produce them in the volumes exported to Russia. To support this, imports of these same articles from EU countries have risen during this time; imports from China likewise surged in 2022 compared to Beijing’s exports to other countries.

A new package of sanctions adopted by the EU in December 2023 that includes a “no re-export to Russia” requirement for all exporters to third countries, as well as the U.S. Commerce Department’s measures to curb the diversion of export-controlled items, may lower the volumes of official exports from EEU member-states to Russia in 2024. While the short-term benefits of reselling goods to Russia may decline and the risks of parallel trade may grow, certain socio-economic imperatives nevertheless look set to increase cooperation between the EEU member-states, plus Uzbekistan, and Russia.

Figure 1. Annual GDP Growth (%) in EEU Member-States, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan

Source: World Bank national accounts data and OECD National Accounts data. Belarus’ 2023 GDP growth is based on official reports by the Belarusian Statistical Agency.

Moscow’s search for new hydrocarbons markets aligned well with the high demand for energy in the Central Asian republics, which had been plagued by power outages and shortages of fuel. Flaunting its cheap energy prices and other incentives to the EEU member-states, Russia proposed the creation of common gas, oil, and electricity markets within the Union, with some projects including Uzbekistan. While both Tashkent and Astana have denied the establishment of a “tripartite gas union,” Russia’s Gazprom has signed contracts with Kazakhstan for gas transit to Uzbekistan and has been negotiating longer-term contracts for Russian gas transit through Central Asia to third countries. In addition to gas transit and supplies, the Central Asian governments and business elites reap benefits from the increased supply of Russia’s petroleum products, which are critical for social stability in the region, and Russian investments in the dilapidated electricity sector.

Figure 2. Exports of EEU Member-States, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan, to Russia (US$ Thousand)

Source: World Bank Enterprise Surveys through World Integrated Trade Solution, https://wits.worldbank.org/Default.aspx?lang=en

There are also longer-term prospects for turning EEU member-states into critical hubs for international logistics and transport. At the end of 2023, the EEU members announced a permanent pact with Iran designed to facilitate trade between Tehran and members of the EEU by removing certain tariff and customs barriers. In early 2024, the EEU members held discussions with India that inaugurated formal negotiations over a free trade agreement with New Delhi. The United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Indonesia have been negotiating similar measures. These initiatives are all part of a broader plan for an ambitious transport corridor that would connect Russia’s St. Petersburg to India’s Mumbai through a network of rail links, sea routes, and highways branching out into Asian and Middle Eastern trade markets.

First envisioned in 2000, the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) was dormant until the weight of Western sanctions forced a reorientation of Moscow’s trade. The INSTC consists of the three main routes. The Western route crosses Russia’s southern regions and runs via a railway network through Azerbaijan and Iran, going on to Mumbai via sea. The route passes by ports in the Persian Gulf, presenting an opportunity for branching out to markets in the Middle East. It is the most developed of the three routes both diplomatically and in terms of the quality of the transport infrastructure, and promises significant reductions in delivery time compared to the traditional route from St. Petersburg to Mumbai that runs around Europe from Russia’s Baltic sea port through the Suez Canal. The second, Trans-Caspian, route passes through the Caspian Sea by ship and proceeds through Turkmenistan and Iran to India. The third, Eastern, route links the Kazakh port of Aktau and the northern ports of Iran.

The INSTC has clear short- and long-term benefits for Russia. The alternative routes will enable Moscow to continue circumventing Western sanctions and complete its pivot to Indo-Pacific and Asian markets. In the long run, the INSTC will allow the Kremlin to build trade bridges to the Middle East and promote economic growth in Russia’s restive southern regions, where large segments of the Russian portion of the INSTC are located.

INSTC routes have also been important to Central Asia. The first cargo shipment from Russia to India via the Eastern route took place in July 2022, and in 2023 the railway companies of Russia, Iran, and Kazakhstan created a new venture to streamline transport logistics along the route. Turkmenistan has become increasingly interested in connecting to the INSTC, while Kazakhstan aims to become a transit hub that hosts the intersection of the INSTC and its competitor, the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (known as the Middle Corridor), backed by the US and the European Union. While both projects face considerable logistical and political hurdles, the Central Asian countries stand to benefit from the political attention, infrastructure investments, and access to new markets that they bring.

The Future of the Collective Security Treaty Organization

Like the EEU, the CSTO—a security alliance comprised of Russia, Armenia, Belarus Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan—has been dubbed a “lifeless, shambling ‘alliance,’” its decline precipitated by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Kyrgyzstan’s cancellation of the 2022 CSTO exercises on its territory in the wake of violent Kyrgyz-Tajik clashes and Armenia’s suspension of its membership in the organization, which Yerevan blasted as “ineffective” in resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict with Azerbaijan, have magnified internal rifts in the military alliance.

Indeed, the CSTO has never conformed to the ideas of collective security exemplified by NATO. Instead, it has become a vehicle for achieving the diverse interests of the political and military elites of its member-states, and these interests have often prevailed over the common objectives of the military alliance. So long as the CSTO can benefit the leadership of its member-states and these benefits exceed the risks associated with the membership in the organization, the CSTO will persist—for three main reasons.

First, the CSTO has played an important legitimizing and stabilizing role for its authoritarian members, throwing its support behind autocratic leaders in crisis, as it did in Kazakhstan during the “Bloody January” events of 2022. As all CSTO members have seen authoritarian regeneration, the CSTO is bound to be used as a platform of authoritarian solidarity for regimes that eschew meaningful democratization.

Second, following the fall of the first Taliban regime, the home-grown terrorist groups who had found safe haven in Afghanistan were a major concern for the Central Asian governments. Russia promptly capitalized on these anxieties to spearhead counterterrorism exercises under the auspices of the CSTO and the Anti-Terrorism Center (ATC) of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan continue to express concerns about the situation in Afghanistan, while Tajikistan, which supports the anti-Taliban National Resistance front, has acrimonious relations with its southern neighbor. The Central Asian governments have a shared interest in anti-terrorism drills, which remain on the CSTO agenda. The Tajik authorities have called on the CSTO to assist with security challenges emanating from Afghanistan, and a tentative plan for the CSTO to play a role in defending the Tajik-Afghan border has been under review by its members in 2024.

Third, military cooperation and security assistance under the auspices of the CSTO remain a decisive factor in its continuation. All CSTO members receive military equipment from Russia at highly discounted rates and their officers are trained at Russia’s military institutions. Moscow is the leading supplier of weapons and weapons systems to the CSTO countries. Given the makeup of CSTO countries’ weapons inventories, Moscow will remain their major provider of parts and ammunitions for years to come. While all CSTO countries have sought to diversity their security ties through the Partnership for Peace program with NATO, as well as bilateral and multilateral security cooperation initiatives with other countries, their membership in the CSTO has limited their aperture for security cooperation outside the organization.

This combination of material and political gains, limitations on security cooperation outside the CSTO, and a lack of external actors capable of meeting the needs of CSTO-member governments on terms amenable to the ruling elites contributes to the CSTO’s persistence.

Conclusion

The failure of Russia’s institutionalism in Eurasia has not meant the demise of the projects that were ostensibly created to facilitate the political, economic, and military integration of the region. Even “bad” institutions can be sticky. This stickiness lies in the ability of the EEU and CSTO to offer mechanisms to harness opportunities and hedge against risks to their member-states’ ruling elites. The traditional institutional deficiencies of these organizations are simultaneously the sources of their persistence, as they allow their members to adapt and repurpose the rules, relationships, and processes developed within the frameworks of the EEU and CSTO to suit the particularistic interests of individual regimes.

To do away with these organizations or fundamentally alter their purpose would require meaningful changes to governance among the members or the emergence of alternatives that would function as opportunity and risk management tools. The US and its Western allies face a major challenge in Eurasia, namely the need to balance their priority of countering Russia’s and China’s influence with the specific development and integration needs of the Central Asian states and beyond. Subordinating regional goals to U.S. priorities has historically resulted in downplaying good governance, with the result that short-term incentives and disincentives have derailed these countries’ longer-term transformation. Regional integration initiatives have suffered from a lack of sustained attention from Western donors and a mismatch between lofty ambitions and the limited financial and political resources put forth to support them. Consequently, the Central Asian governments have been left to navigate complex geopolitical and geoeconomic waters on their own using tried-and-tested “multivector” foreign policies, of which the EEU and CSTO can be expected to remain a part.

Dr. Mariya Y. Omelicheva is a Professor of Strategy at National Defense University with

expertise in international and Eurasian security, counterterrorism and human rights,

democracy promotion, gender and security, and crime-terror nexus in Eurasia.