The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine has intensified concerns about support for Russia among ethnic Russians and Russian-speaking populations in the former Soviet Union. In countries ranging from Kazakhstan to Lithuania, ethnic Russians and Russian-speakers have been framed as a potential fifth column. The Russian government and its propagandists have done much to encourage this framing, using false claims about protecting Russian-speakers as a casus belli for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, the resistance to Russia’s invasion in historically Russian-speaking regions of Ukraine—such as Odesa and Kharkiv—has complicated this story, demonstrating that speaking a common language does not predetermine support for Russian irredentism.

Analyses of data from a 2023 survey of the largely Russian-speaking Moldovan region of Gagauz Yeri (GY) further complicate the link between Russian-speaking populations and support for Russia. Even though this population evinces very high levels of support for some aspects of Russian politics, this support is not universal. For example, although GY’s population overwhelmingly supports Vladimir Putin, only a minority supports Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Moreover, while residents of GY prefer many aspects of the Russian political system to those of Moldova, they prefer their region’s status as an autonomous region of Moldova to integration with Russia. More broadly, being a fluent Russian-speaker in GY does not universally correlate with higher support for different aspects of Russian politics, though there is some evidence that frequent exposure to Russian-language media does so more consistently.

These data clearly show that even high levels of support for different aspects of Russia’s political system do not imply support for Russian irredentism. Scholars and policymakers working with Russian-speaking populations should thus avoid conflating support for some aspects of Russian politics with universal support for Russian policies.

The Linguistic and Political Situation in GY

GY is an autonomous region located in the south of the central European country of Moldova. According to the 2014 Moldovan Census, GY has 134,535 residents. Approximately 84 percent of these residents are ethnic Gagauz (the region’s titular group), with ethnic Bulgarians and Moldovans each making up an additional five percent of the region’s population. Ethnic Russians constitute approximately three percent of GY’s population.

In 1990, the GY regional government declared itself directly subordinate to the government of the Soviet Union, in effect seceding from what was then the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1994, however, the regional government signed an agreement to reintegrate into the now-independent Republic of Moldova. Since then, relations between the Moldovan central government and that of GY have often been tense, especially with regard to issues concerning European integration and relations with Russia. Indeed, in a 2014 referendum, the population of GY overwhelmingly voted in favor of joining a Russia-backed trade union and against greater integration with the European Union; residents also reiterated their right to secede from Moldova should Moldova lose its independence. More recently, the region elected a Russia-backed politician as its Başkan (Governor) in May 2023, over the strong concerns of the Moldovan central government.

These pro-Russian political leanings mirror the region’s linguistic situation. Although the Gagauz have traditionally spoken a Turkic language, the region’s Soviet history resulted in widespread use of the Russian language. Approximately 96 percent of respondents in the 2023 survey report speaking Russian fluently, compared to 74 percent for Gagauz and 12 percent for Romanian/Moldovan.[1] Ninety-eight percent of respondents indicated that Russian is used either frequently or almost all the time in GY; 93 percent stated that it is spoken either as frequently or more frequently than Gagauz, the second most frequently spoken language in GY.

This confluence of a Russian-speaking population and apparent pro-Russian sentiment makes GY an excellent case for analyzing the relationship between these two factors. Moreover, given the ongoing threat that Russia poses to Moldova’s territorial integrity, understanding the roots of support for Russia within Moldova is of clear policy importance.

Forms of Support for Russia

In this memo, I focus on three different forms of support for Russia that the 2023 survey measured: support for 1) Russian politicians and policies, 2) Russia’s political system more broadly, and 3) integration with Russia.[2]

Support for Russian Politicians and Policies

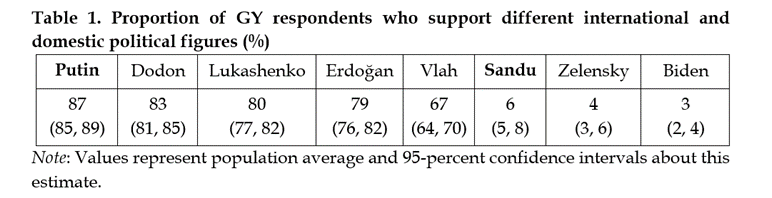

According to the survey data, 87 percent of GY residents support the political activities of Russian President Vladimir Putin. This support is high in both absolute and relative terms. Indeed, it exceeds estimated support for Putin in Russia itself, which ranged from 79 to 83 percent during the same period, according to data from the respected Russian Levada Center. As Table 1 illustrates, this level of support is also high relative to GY inhabitants’ support for other international and domestic political figures.[3] In addition to Putin being the most popular politician in the survey, he was dramatically more popular than pro-Western Moldovan President Maia Sandu: only six percent of GY respondents reported supporting Sandu’s political activities.

Notably, however, GY support for Putin’s political activities does not extend to his most prominent recent political activity: only 30 percent (95-percent confidence interval [27 percent, 33 percent]) of respondents reported supporting Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.[4] In other words, even a very high level of support for the Russian president does not imply support for all of his policies.

Support for Russia’s Political System

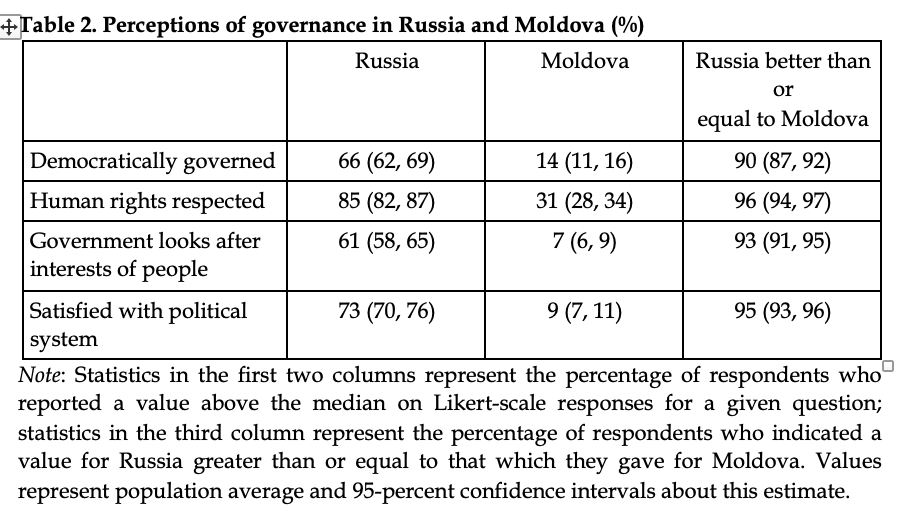

As Table 2 illustrates, residents of GY overwhelmingly perceive Russia’s political system as preferable to that of Moldova. Ninety percent of respondents expressed a belief that Russia is more or equally democratically governed than Moldova; 96 percent stated that there is greater or equal respect for human rights in Russia than in Moldova.[5] Moreover, 93 percent of respondents expressed a belief that the Russian government looks after the interests of people like them to a greater or equal extent to the Moldovan government. It is therefore unsurprising that 95 percent of respondents indicated that they would be more or equally satisfied with the functioning of the Russian political system—if they were a resident of Russia—than they are with the functioning of the Moldovan political system.

Support for Political Integration with Russia

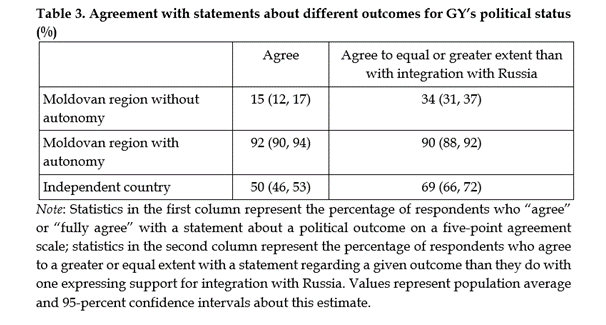

As with the disconnect between support for Putin and Russia’s military activities in Ukraine, GY residents’ support for the Russian political system does not translate into a desire to integrate with Russia. While 68 percent (95-percent confidence interval [65 percent, 71 percent]) of GY residents agreed or fully agreed with the statement that GY should be part of Russia, 90 percent of respondents agreed to an equal or greater extent with a statement in support of the status quo: GY should be part of Moldova with autonomy. Indeed, when asked to choose their preferred outcome for Moldovan-GY relations from a list of alternatives, a significant majority of GY respondents (72 percent) selected the status quo (autonomous status within Moldova), compared to six percent who selected a confederation with Moldova and 19 percent who selected independence (only four percent selected remaining within Moldova without autonomy).

The Link between Speaking Russian and Supporting Russia

In addition to these region-wide analyses, it is possible to disaggregate speakers and non-speakers of Russian to assess the relationship between speaking Russian and supporting Russia.[6] However, much as regional support for Russia varies depending on the form of support, different traits associated with Russian identity—including those associated with speaking Russian—likely have different political implications. I therefore analyze two traits associated with speaking Russian: self-reported 1) Russian-language fluency and 2) frequency of watching television in Russian. I examine the relationship between these traits and four previously discussed forms of support for Russia: 1) support for Russian President Putin; 2) support for Russian military activities in Ukraine; 3) perceived satisfaction with the Russian political system; and 4) agreement with the statement that GY should be part of Russia.

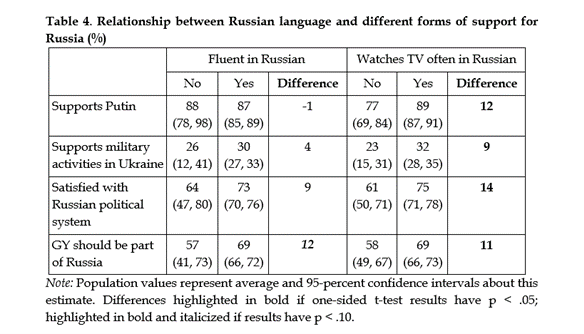

Table 4 reports the results of these analyses. As previous research has suggested, fluent speakers of Russian tended to be more supportive of integration with Russia than did non-speakers. However, there was no clear relationship between fluency in Russian and any other form of support for Russia.[7]

On the other hand, respondents who reported watching Russian TV either “often” or “very often”—the top two items on a five-point scale looking at frequency of Russian-language media consumption—tended to be more supportive of Russia across all four items. This set of results is in line with research finding that access to Russian-language propaganda increases support for pro-Russian policies.

Conclusion

The analyses in this memo lend themselves to two main conclusions. First, even high support for some aspects of Russian politics does not imply universal support for Russian political activities, including—and especially—the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Second, being a fluent Russian-speaker in a post-Soviet region does not necessarily correlate with higher support for any given Russian political activity, though there is some evidence that frequent exposure to Russian-language media does. The most important implication of these results—for policymakers and academics alike—is that it is necessary to be specific when discussing support for Russia. Not only is there no clear, consistent link between speaking Russian and support for Russia (in various forms), but support for Russia on one metric does not necessarily indicate support for Russia on any other.

In the specific context of GY, the data clearly demonstrate that support for the Russian President and the Russian political system do not translate into support for Russian irredentism toward either Ukraine or Moldova. Conflating these forms of support is thus highly misleading.

As a final note, I emphasize that it is a gross oversimplification to reduce GY identity to speaking Russian and support for Russia. As with other Russian-speaking populations in the former Soviet Union, GY’s idiosyncratic historical and institutional circumstances mean that a variety of aspects of identity are highly salient for GY political behavior. To wit, GY regional identity is clearly an important aspect of GY politics: 62 percent of respondents reported that they considered themselves “very much” or “completely” patriots of GY, compared to much smaller—and roughly equal—percentages who considered themselves patriots of Russia (41 percent) or Moldova (40 percent).

Funding

A University of Bergen Department of Comparative Politics Småforsk research grant funded this research project.

Kyle L. Marquardt is Associate Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen.

[1] In March 2023, the Moldovan Parliament voted to use “Romanian” to refer to the state language (previously known as “Moldovan”). This decision has been controversial, and a majority of residents of some Moldovan regions (including GY) prefer the continued use of “Moldovan.”

[2] The Moldovan research firm IMAS Inc conducted the regionally representative survey between November 2022 and April 2023; it includes 1,024 respondents.

[3] Aside from Putin and Sandu, Table 1 includes data for the following figures: Igor Dodon, the pro-Russian former president of Moldova (2016-2020); Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko; Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan; outgoing GY Başkan Irina Vlah; Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky; and U.S. President Joseph Biden. The survey did not include data on current GY Başkan Evgheniya Guțul, who was elected in a May 2023 run-off election after the survey was completed.

[4] The survey used the innocuous framing “Do you support Russia’s military activities in Ukraine?” While this framing was necessary to avoid framing effects, it likely inflates estimated support for these activities.

[5] Though both democracy and human rights are difficult concepts to measure, these opinions run counter to the scholarly consensus. For example, Moldova had a score of .90—compared to Russia’s .31—in the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Civil Liberties Index for 2022, where scores closer to 1 represent greater respect for human rights and scores closer to 0 represent lesser respect. Similarly, Moldova received a score of .75—compared to Russia’s .21—on the V-Dem electoral democracy index, a difference equivalent to roughly half the scale (.54 on a 0 to 1 scale).

[6] These analyses are purely correlational, not causal: a statistically significant relationship does not imply that a trait associated with speaking Russian causes any given form of support for Russia.

[7] This lack of a relationship may be due in part to the low sample size of non-fluent speakers of Russian.