Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2014, an armed conflict over the Donbas region has resulted in nearly 8,000 people dead, more than 10,000 wounded, and over 1.1 million displaced, according to the United Nations. Aside from continuing loss of life, social research suggests that a sustained violent conflict could also radicalize Ukraine’s internal ethno-cultural and political divides. At stake are fundamental processes in Ukrainian society and politics in the coming years—will we see Ukraine move toward social inclusiveness and law-based political pluralism or toward ethnocentrism, social radicalism, and authoritarianism? Would a continuing armed conflict strengthen public enthusiasm for difficult reforms to bring Ukraine into the European Union and NATO, or would it breed disillusionment with the West and revive support for Ukraine’s integration with Russia?

To address these questions, I review publicly available data from methodologically rigorous mass opinion surveys in Ukraine before and after the onset of the armed conflict in the Donbas. On the whole, the Ukrainian society deserves commendation. A spike in national pride has by and large not been accompanied by an increase in social or political intolerance. Moreover, in some important respects the Ukrainian public may be turning more socially tolerant. Support for democracy as a form of government has also remained strong.

Yet the data also warns against complacency. Positive trends are still fragile and some regional differences have hardened. Within Donbas territories under control of the Russia-backed separatists, xenophobic views have increased markedly. On some indicators, support for integration with the European Union—associated with inclusive social and political values—has softened since mid-2014, including in western Ukraine.

War, Identity, and Values

Existing research is at best inconclusive when it comes to specific social and political effects of armed conflicts such as the one in Ukraine. We have studied much more how identities make war than how war makes identities. On the one hand, exposure to war appears to make national, ethnic, and religious identities more rigid and antagonistic. Wars over territory when these identities are at stake are typically longer and deadlier than average. In a recent statistical analysis of over one hundred opinion surveys in 69 countries from 1989 to 2008, political scientists Jaroslav Tir and Shane Singh found that in states that had experienced a territorial armed conflict with more than 1,000 casualties, public acceptance of other social groups as neighbors dropped on average by half within a year. Other survey-based studies found that exposure to violence increased a denial of civil liberties to groups cast as enemies and strengthened or amplified social support for authoritarianism. In a 2013 study of survey data from Bosnia, Kosovo, and Croatia, Karin Dyrstad also found that these negative effects could last over a decade after the armed conflict ended.

On the other hand, psychologists have found that victims of violence typically become more resilient and open-minded. Political scientist Christopher Blattman has shown that former civil war combatants in Uganda were systematically more likely than average to vote and work as community leaders—i.e., engage in fundamentally democratic political behavior. Moreover, findings of negative war effects mostly come from the analysis of civil wars, whereas the conflict over Donbas in military terms is predominantly an interstate war; most military capabilities accounting for death and destruction (multiple-rocket and missile systems and heavy artillery) are fielded by the governments of Ukraine and Russia (the latter’s official denials notwithstanding). Existing research indicates that interstate territorial wars could make national civic identities more inclusive and tolerant, while ethnic identities may be affected differently within and outside of conflict zones. War in defense of democratic values against an external threat could well strengthen adherence to those values.

With these conflicting arguments in mind, I examined the Ukrainian survey data for commonly used indicators of national and ethnocultural identities, political system preferences, and geopolitical orientation before and after February 2014.

National Pride

Across Ukraine, the most notable change in public opinion trends since the start of the armed conflict is a spike in civic national pride and sense of national belonging.

- An overwhelming majority of the public has come to support independent statehood for Ukraine. Support gradually built up since 1991, through fits and starts, but the war in the Donbas has turned it into a social given. According to multiyear surveys conducted by a well-established polling center of the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, support for independent statehood rose from the lowest point of 56 percent in 1993 to 83 percent in 2013 and reached 90 percent in mid-2014.

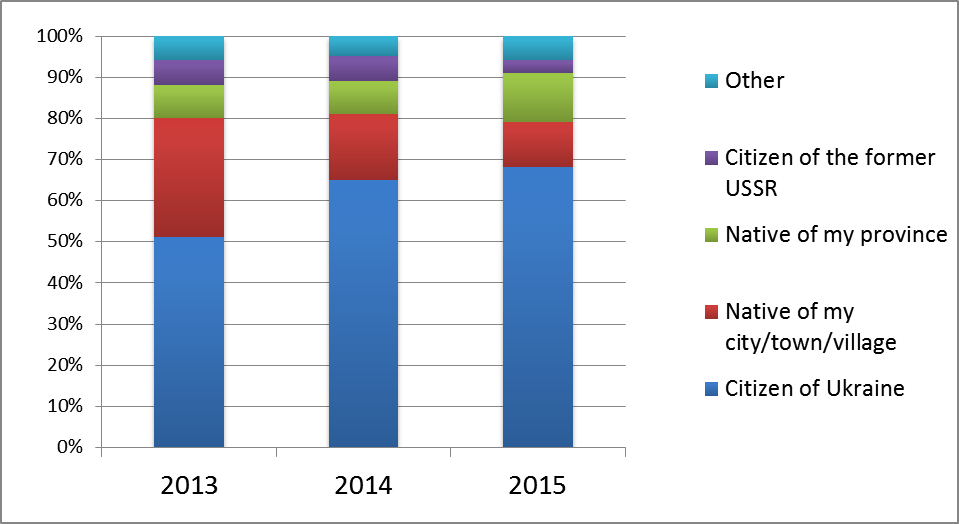

- National identity has strengthened, predominantly at the expense of local and Soviet identities. The number of people identifying themselves first and foremost as citizens of Ukraine has increased from 51 percent in 2013 to 68 percent in 2015, as the number of people saying they were primarily citizens of their native town, city, or province, or the former Soviet Union declined. Practically no one primarily identified with his or her own ethnicity (Figure 1).

- Support for Ukraine remaining a unitary state rose sharply and remained strong in the east of the country. The number of respondents in surveys by the reputable Razumkov Center who opposed granting autonomous status to their provinces went up from 56 percent in 2013 to 62 percent in 2014 and to 79 percent in 2015. In a regionally stratified study by the Institute of Sociology in 2015, nearly two thirds of respondents in Donetsk and Luhansk provinces under Ukrainian government control opposed autonomy and only 14 percent supported it. In Ukraine’s southern regions (Mykolayiv, Odessa, and Kherson), 72 percent of respondents opposed and 14 percent supported their regions’ autonomy.

Ethnocultural Sensibility

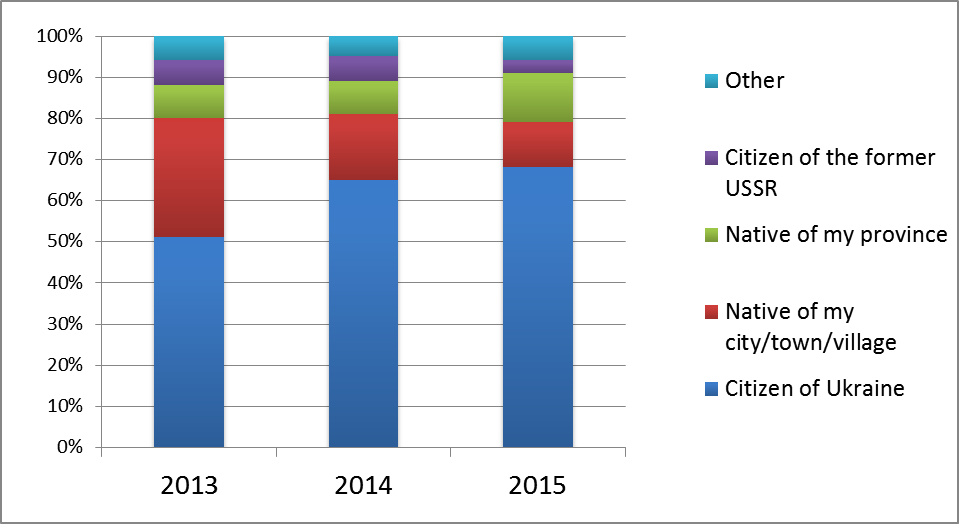

While ethnic and linguistic identifications changed little, in 2015 respondents reported that they speak slightly more often than before only Ukrainian at home or speak both Ukrainian and Russian, while preference for speaking only Russian somewhat dropped compared to previous years. These changes are still largely within the margin of sampling error, except for those regarding a difference in preference to speak Russian or Ukrainian, which widened. It may also be that these differences reflect longer-term social trends not necessarily related to conflict with Russia over Crimea or the Donbas (Figure 2).

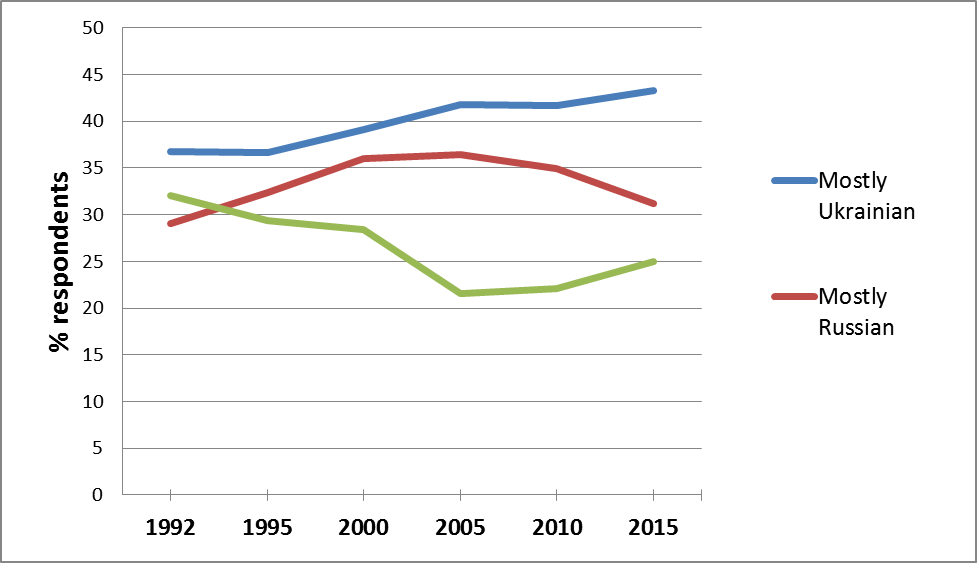

Overall, Ukrainian society has become somewhat less xenophobic—judging by detailed regionally stratified mass surveys of the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) that have tracked intergroup relations in Ukraine since 1994. Each year, approximately 2,000 respondents across Ukraine have been asked if they would accept members of 13 ethnic or national groups other than their own as family members, friends, neighbors, co-workers, other citizens, or tourists, if at all. On the resulting scale where “1” stands for full acceptance and “7” stands for zero acceptance, the highest score was 4.7 registered in 2009. From 2010 to 2014, the score remained just under 4.5.

The surveys in October 2014, however, revealed important caveats:

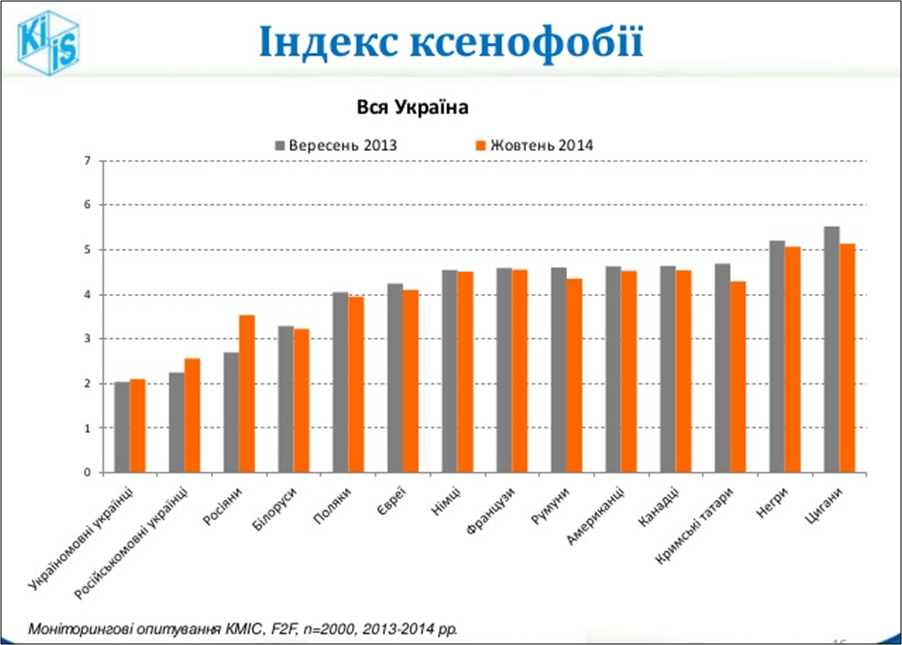

- Across Ukraine, acceptance of all groups somewhat increased—except for groups associated with Russia (Russians and Russian-speaking Ukrainians), which decreased (Figure 3).

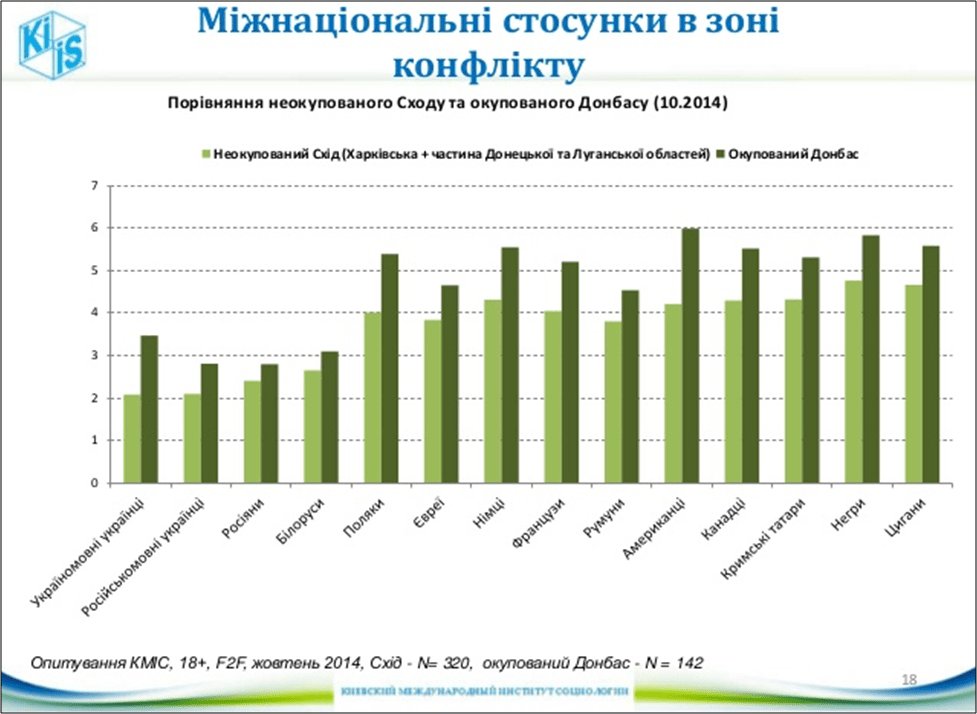

- Xenophobic views hardened substantially in the separatist-controlled part of the Donbas. In 2014, respondents there expressed more intolerant views vis-à-vis all groups compared to respondents in Kharkiv province and in the government-controlled part of the Donbas. This difference most likely reflects the impact of the war. The largest difference in hostility was toward Americans (4.0 in government-controlled areas vs. 6.0 in the Russia-backed separatist controlled areas). This is consistent with the Kremlin’s framing of the United States as the instigator of the Euromaidan and the ouster of former president Viktor Yanukovych and thus unlikely to have been present in mid-2013 (Figure 4).

As before the onset of the armed conflict, the overwhelming majority of Ukraine’s residents in early 2015 considered themselves Orthodox Christians—except in the west where most respondents identified with the Uniate (Greek Catholic) church. However, a major shift took place within the Orthodox community. A significantly number of respondents shifted their preference from the patriarchate based in Moscow to the patriarchate based in Kyiv between 2013 and 2015 (Table 1). However, mutual perception of religions associated with Ukraine’s regional—and recent geopolitical—divisions have been overwhelmingly tolerant.

- Across Ukraine, about 40 percent of respondents in a 2015 Democratic Initiatives Fund survey (with 4,413 respondents) said that both the Moscow-based Orthodox Church and the western Ukraine-centered Greek Catholic church are “just one of the churches that exist in Ukraine” and an additional 20 percent said they did not care what these churches may represent.

- Only in western Ukraine (Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv, and Ternopil provinces) one observes an exception from this relatively benign/neutral view, with about 42 percent of respondents naming the Moscow-based Orthodox Church in Ukraine “the church of an aggressor state that conducts harmful activities in Ukraine.” For Ukraine as a whole, this response option was picked by just about 19 percent of respondents. In government-controlled areas of the Donbas, however, one does not find significant negative views of the Greek Catholic Church—only 1.5 percent of respondents there (compared to 3.7 percent in Ukraine at large) said it was a “dried-out branch of Christianity, an artificial religious union.”

Democratic Resilience

Since the outbreak of the war in the Donbas, most residents of Ukraine have persisted in their support for democracy. This support appears to run deep. At the same time, support for extreme political views has remained marginal.

- Having risen sharply before the Maidan revolution, public support for democracy remained high despite the war. In nationwide surveys by the Razumkov Center and the Democratic Initiatives Fund (with about 2,000 respondents each), the number of respondents who said democracy was the best form of government for Ukraine rose from 37 percent in 2009 to 50 percent in 2012 and to 53 percent in December 2014. The number of respondents in the same surveys who said that under certain conditions an authoritarian system could be better dropped from 30 percent in 2009 to 20 percent in 2012 and to 19 percent in 2014.

- When asked if they would be willing to trade some of their rights and freedoms for stronger government authority in exchange for personal well-being, in December 2014 24.5 percent of respondents across Ukraine agreed. However, almost twice as many respondents (40.2 percent) said they would be willing to sustain material hardship in exchange for their personal freedoms and civil rights being observed as before.

- Only a very small percentage of respondents in various polls said they would vote for the parties typically placed on the extreme right or left of Ukraine’s political spectrum. If anything, such support most likely declined as the military conflict in Donbas flared (Table 2). The data is only broadly indicative of any trend, however, because levels of public support for these parties have been so small that all differences are within the sampling error margins.

Europe Pivotal

Since the onset of armed conflict in the Donbas in March 2014, public support in Ukraine for closer relations with Europe, including joining the EU and NATO, has increased as support for integrating or dealing with Russia in general has declined.

- In Razumkov Center surveys, the number of those who believed Ukraine’s foreign policy priority was relations with Europe increased from 42 percent in 2012 to 53 percent by the end of May 2014. At the same time, the number of respondents who believed Ukraine should pivot to Russia declined twofold, from 35 to 17 percent. The number of those supporting priority relations with other countries stayed about the same.

- If a referendum were held in Ukraine in May 2015, about 63 percent of likely voters would support Ukraine joining the EU, based on a KIIS survey. The rest would oppose it. This is based on an estimated turnout of 77 percent.

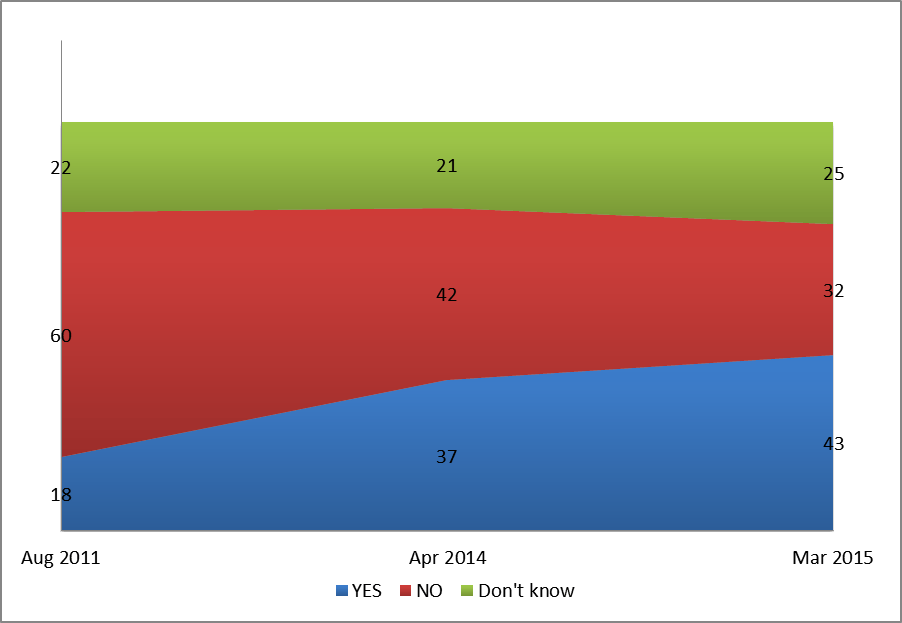

- Public support for Ukraine joining NATO rose rapidly from 2011 to 2014 and continued to increase through 2015, according to Razumkov Center polls (Figure 5). The data strongly suggests that the same trend also obtained in Ukraine’s eastern provinces—in April 2014 about 29 percent of respondents there supported and 53 percent opposed NATO membership. This level of public support is significantly higher than 18 percent across all Ukraine back in 2011.

- Support for Ukraine uniting with Russia in a single state—sizeable in mid-2013 before the conflict—has practically disappeared, including in Ukraine’s eastern regions under government control. According to the regular KIIS Omnibus surveys of Ukraine’s adult population, about 20 percent of residents in Ukraine’s south and 28 percent in the east supported unification with Russia in May 2013. But only 2 percent of respondents in the south and 6 percent in the east supported this idea in May 2015.

The same May 2015 KIIS poll also suggested that the pro-Europe orientation should not be taken for granted. Compared to the institute’s poll in December 2014, a willingness to join the EU somewhat declined across Ukraine—from 88 to 78 percent in the west; from 62 to 57 percent in central Ukraine; and from 38 to 33 percent in the south (without Crimea). In government-controlled parts of the east, support for joining the EU remained at about the same level at 21 percent.

While only in western Ukraine was the change greater than the margin of sampling error, declining enthusiasm about joining the EU could undercut socially and politically tolerant views. In an April 2014 KIIS survey, respondents said their support for integration with the EU was motivated primarily by pursuit of common political values—individual rights and freedoms (28 percent), democracy (27 percent), the rule of law (14 percent), and respect of the individual (14 percent). Only 12 percent said they were primarily motivated by greater economic prospects. In contrast, support for integration with Russia was predominantly motivated by a sense of common history (46 percent), culture (23 percent), ethnicity (18 percent), and religion (15 percent).

Implications

In the face of war, destruction, and economic hardship, Ukrainian society has persisted in its predominant aspirations for democracy at home and for joining Europe’s democratic union. Considerable room for improvement remains, but temptations for ethnocentrism, xenophobia, political radicalism, and authoritarianism have so far been kept at bay.

Yet having concentrated significant military capabilities around the Donbas and gained control over Ukraine’s land borders in the region, the Kremlin can turn on and off indefinitely the heat in the ongoing armed conflict. Authoritative research suggests that in doing so Moscow could seriously undermine Ukraine’s public support for democracy and social tolerance. The analysis of recent survey data from Ukraine undertaken here shows that Ukraine’s public resilience to these pressures should not be taken for granted.

Much depends on Europe. If Ukraine’s EU integration slows down and NATO membership prospects become murky—particularly if the United States and EU ease economic sanctions on Russia without any progress on Ukraine joining these organizations or regaining control over the Donbas and Crimea—those Ukrainians who aspire to join these institutions and who so far are in the plurality may turn either cynically apathetic or virulently radicalized and intolerant. That would erode public support for democracy and determination to improve government transparency and accountability in Ukraine—some key conditions of integration into the EU. However, this also means the reverse might be true: if the EU and NATO find a way to speed up Ukraine’s membership process (whether by responsibly and creatively changing the rules or designing a legitimate and credible workaround) Ukrainian society might well respond with increased commitment to democratic institutions and behavior. This is not to mention that such an approach might also bring peace back to the Donbas by signaling that if Moscow fuels the armed conflict there in the hope of making Ukraine unpalatable to Europe, it will achieve the opposite result.

Figure 1. “Who do you consider yourself to be first and foremost?” (% of respondents in opinion surveys in Ukraine)

NOTE: Based on the annual Ukrainian sociological monitoring surveys of the Institute of Sociology of Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences in 2013 and 2014 (mid-year) (N=1,800); and the national survey of the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Fund and the Ukrainian Sociology Service (N=4,413) (completed January 15, 2015). “Other” category includes identification as member of one’s ethnic group, Soviet citizen, citizen of Europe, citizen of the world, other, and don’t knows.

Figure 2. Which languages do you speak at home?

NOTE: 2015 data is based on a survey of the Institute of Sociology of Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences (N=1,800, excluding separatist controlled territories in Donbas)and prior years reported in Evhen Golovakha, Natalya Panina, and Olena Parakhonska, “Ukrainian Society 1992-2010: Sociological Monitoring,” National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Institute of Sociology (Kyiv, 2011).

Figure 3. Levels of declining xenophobia (except for ethnic Russians), 2013-2014.

NOTE: Kyiv International Institute of Sociology surveys, Ukraine national sample (N=2,000) conducted in September 2013 (left column in each cluster) and October 2014 (right column in each cluster). Groups, listed under the X-axis, from left to right: Ukrainian-speaking Ukrainians, Russian-speaking Ukrainians, Russians, Belarusians, Poles, Jews, Germans, French, Romanians, Americans, Canadians, Crimean Tatars, ”Blacks,” Gypsies.

Figure 4. Hardening of xenophobic views in the separatist-held territories of the Donbas, compared to the government-controlled areas, 2014.

NOTE: Based on the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology national opinion survey of October 2014, comparing the subsamples for eastern Ukraine (Kharkiv province, plus government controlled parts of Donetsk and Luhansk provinces) (N=320) (left columns) and separatist-controlled parts of Donetsk and Luhansk provinces (N=142) (right columns). Groups, listed under the X-axis, from left to right: Ukrainian-speaking Ukrainians, Russian-speaking Ukrainians, Russians, Belarusians, Poles, Jews, Germans, French, Romanians, Americans, Canadians, Crimean Tatars, “Blacks,“ Gypsies.

Figure 5. Do you support Ukraine joining NATO?

SOURCE: Razumkov Center

Table 1. To which Orthodox Church do you belong?

|

2013

|

2015

|

|

|

Ukrainian Orthodox – Kyiv Patriarchate

|

26

|

38

|

|

Ukrainian Orthodox – Moscow Patriarchate

|

28

|

20

|

|

Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox

|

1

|

1

|

|

Orthodox (no denomination)

|

41

|

39

|

|

Don't know

|

4

|

2

|

SOURCES: The 2013 data is based on a Razumkov Center nationwide sample of 2,010 adult respondents across Ukraine conducted March 1-6 (sampling error estimated not to exceed 2.3 percent with 95 percent confidence). The 2015 data is based on a SOCIS, Reiting Group, and Razumkov Center nationwide sample of 25,000 respondents (approximately 1,000 in every province) conducted February 1-17 (sampling error estimated not to exceed 0.9 percent with 95 confidence). All surveys are beased on multistage random sampling of Ukraine’s adult population. The 2015 survey excluded Crimea and the Russia-backed separatist controlled areas in the Donbas.

Table 2. For which party would you vote if elections were held now?

|

|

Nov 2014

|

May 2015

|

July 2015

|

|

Svoboda

|

4.4

|

3.7

|

2.2

|

|

Right Sector

|

2.1

|

4.4

|

3

|

|

Communist Party

|

3.3

|

1.4

|

1.1

|

NOTE: Respondents were asked about hypothetical voting in national (2014, July 2015) or province-level (May 2015) elections. SOURCES: November 2014: Reiting Group (N=2,000), May 2015: Sofia Center for Sociological Research (N=3,609), July 2015: Sofia Center for Sociological Research (N=2,044). All surveys are based on multistage random sampling of Ukraine’s adult population, conducted in all provinces of Ukraine excluding Crimea and the Russia-backed separatist controlled areas in the Donbas.

Mikhail Alexseev is Professor of Political Science at San Diego State University.

[PDF]

For further reading:

Volodymyr Kulyk, “One Nation, Two Languages? National Identity and Language Policy in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 389, September, 2015

Henry E. Hale, Nadiya Kravets, and Olga Onuch, “Can Federalism Unite Ukraine in a Peace Deal?,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 379, August, 2015

Scott Radnitz, “The Psychological Logic of Protracted Conflict in Ukraine,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 343, September, 2014