(PONARS Policy Memo) Ethnic Uzbeks conducted four terrorist attacks in the past two years. Sayfullo Saipov, a 29-year-old Uzbek, killed eight people with a Home Depot truck in New York City on October 31, 2017. Thirty-nine-year-old Rakhmat Akilov carried out a similar truck attack that killed four in Stockholm in April 2017. Thirty-four-year-old Abdulkadir Masharipov is currently on trial for killing 39 at a Turkish nightclub on New Year’s Day, 2017. And an Uzbek was one of the three terrorists who killed 44 people in an attack on the Istanbul airport in June 2016.

Analysts have offered two hypotheses for these recent terror attacks. First, several scholars note that these men radicalized abroad and, as such, it is the migrant experience, not the Uzbek experience in Central Asia, which holds the clues to radicalization. Other analysts believe that there is something about Uzbek culture, a posited greater religiosity and acceptance of radical Islamist ideology, that moves some Uzbeks to terror. Drawing on a recent survey of ethnic Uzbeks and Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan, I offer a third possibility: past exposure to violent conflict makes individuals more accepting of violence in defense of religion and it is this altered perception of violence that, in turn, inclines some individuals toward radicalization once they are abroad. This precursor of radicalization is notably different than the religious- and identity-based precursors that candidate and now-President Donald Trump has articulated in successive iterations of the travel ban. Turning away refugees seeking an escape from deadly conflict, for many Americans no doubt, is anathema. Equally problematic, however, is a travel ban motivated by the unsubstantiated logic that national, ethnic, or religious identities predispose entire populations toward militancy.

The Radicalized Abroad Logic

Beset with media inquiries following the sudden spate of terror attacks committed by ethnic Uzbeks, Central Asian scholars have cautioned against concluding Uzbek culture is somehow a hothouse for militant Islam. Erica Marat, a professor and scholar of Central Asia at the National Defense University, explains, “Patterns of radicalization for Uzbeks are somewhat similar to that of migrants from other countries, an inability to fit into the society where [they] live, an inability to live the American dream… they are looking for ways to belong and extremist narratives seem to be the most attractive.” Marlene Laruelle, professor and director of the Central Asian Program at George Washington University, writes that Uzbek terrorism is “a result of difficult integration processes in host countries.” And Politics Professor John Heathershaw of Exeter University urges, “We can’t assume that someone seven or eight years ago left their home country with an intention of joining a militant group and launching an attack… we need to look for an explanation [sic] are some specific recruitment networks within Central Asian migrant communities and diaspora communities.”

The logic Marat, Laruelle, and Heathershaw highlight—that ethnic Uzbek terrorists radicalized abroad and not at home—would suggest that Trump’s directive to increase “extreme vetting” in the immediate aftermath of the October 31 New York City attack is misguided. Extreme vetting is predicated on the idea that there is a militant profile and that Homeland Security can identify potential militants before they enter the United States. At times, Trump has suggested that religion alone is enough for profiling. In the wake of the December 2015 San Bernardino shootings, the Trump campaign announced: “Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what is going on.” President Trump’s “Executive Order Protecting The Nation From Foreign Terrorist Entry Into The United States” and its ban on travelers from six Muslim majority countries is partial fulfillment of this pre-election stance.

The Logic Behind: “Uzbeks Are More Likely to be Radical”

Not all Central Asian analysts, it should be noted, disagree with the logic behind Trump’s extreme vetting. Pulat Ahunov, an Uzbek analyst in Sweden, told EurasiaNet.org: “Uzbeks are of their own right very religious people, and so if they gravitate into extremist-minded circles abroad, they become very easy to manipulate.” Viktor Mikhailov, editor of Nuz.uz, suggests that since the Uzbek government keeps such close watch over religion, “there is no room for radicalism in Uzbekistan, that is why they (radical Islamists) leave.” And Alisher Siddique, Director of RFE/RL’s Uzbek Service, noted at a November 15, 2017, talk at George Washington University, “Uzbeks have a trademark on the black [Islamist] flag. They first raised it during the 1991 Namangan uprising. As Uzbeks, we must begin to ask what is wrong with us.”

Siddique’s lament, along with Ahunov’s and Mikhailov’s observations, offer an alternative to the radicalized abroad logic that Marat, Laruelle, and Heathershaw advance. Perhaps four high profile terrorist attacks conducted by ethnic Uzbeks in the span of two years is not mere coincidence. Perhaps there is something about Uzbek culture that inclines some Uzbeks toward violence in the name of religion.

This question of violence in defense of religion is one that the Pew Foundation explored in a series of surveys conducted in 39 countries between 2008 and 2012. The central findings of these surveys, reported in Pew’s 2013 study “The World’s Muslims,” demonstrate that most Muslims do not support violence in defense of religion. Seventy-two percent of all Muslims surveyed fully reject the idea that “suicide bombing and other forms of violence against civilian targets are justified in order to defend Islam from its enemies.” Considerable variation exists, however, in country level responses to this question. Whereas 81 percent of Muslims in the United States reject violence in the defense of religion, 40 percent of those surveyed in the Palestinian territories, 39 percent of respondents in Afghanistan, and 29 percent of respondents in Egypt did believe that violence against civilians was sometimes justified in defense of Islam.

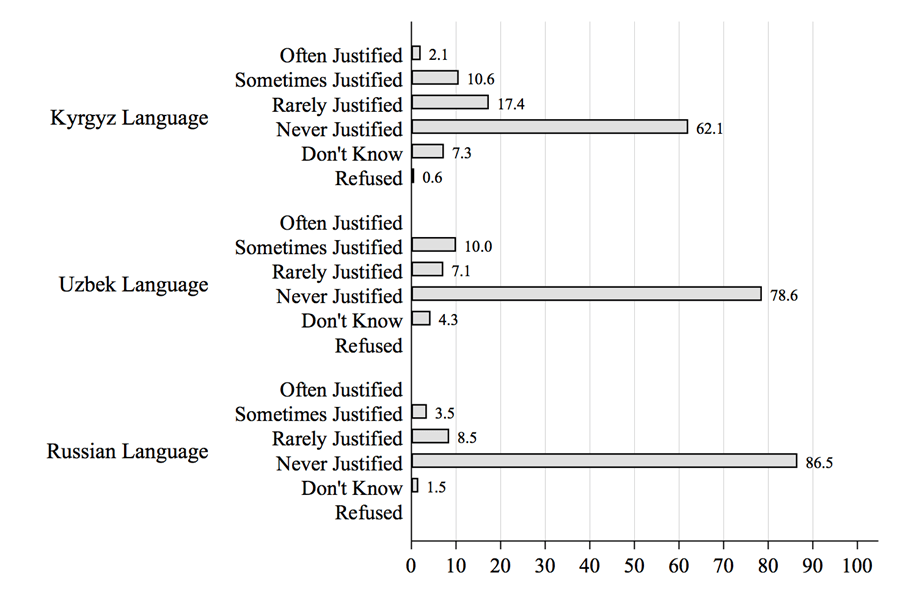

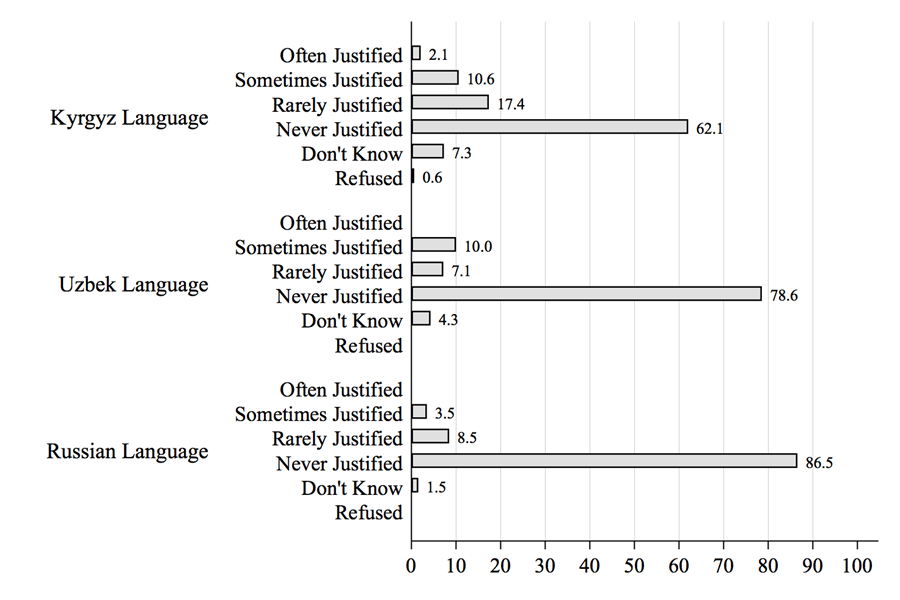

Pew polled Muslims in three Central Asian countries, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, and found that here too considerable variation exists in support for violence in defense of religion. In Kazakhstan 93 percent of respondents said such violence was never justified while 76 percent of respondents in Tajikistan and 66 percent of respondents in Kyrgyzstan disapproved of violence against civilians in defense of religion. While Pew did not poll Uzbeks in Uzbekistan about violence in defense of religion, Pew’s 2012 Kyrgyzstan survey does contain a significant number of Uzbek respondents (70 of 1,292 total respondents). In Figure 1 below, I summarize perceptions of violence in defense of Islam by the language in which the interview was conducted. Language here serves as a proxy for ethnic identity. Language, I should note, is not a perfect proxy for ethnicity. While the overlap between ethnic identity and chosen survey interview language may be near 100 percent for the categories used here, Kyrgyz and Uzbek, respondents who selected Russian as their preferred language are likely a mixture of ethnic Kyrgyz, ethnic Uzbeks, and potentially a few ethnic Russians who self-identify as Muslim.

Figure 1. Percent Response: Violence Against Civilian Targets Is Justified in Order to Defend Islam from Its Enemies—by Interview Language (Pew 2012 Kyrgyzstan Survey)

These survey results provide some evidence in support of the hypothesis that Uzbek and Kyrgyz language speakers are more inclined toward violence in defense of Islam than is the general Muslim population in the United States. That said, Uzbek language respondents in the 2012 Pew survey reject violence (78.6 percent) at only slightly lower rates than do U.S. respondents (81 percent). Nevertheless, a proponent of extreme vetting might seize on the comparatively low number of Kyrgyz language respondents (62.1 percent) who reject violence in defense of religion and conclude that Central Asian Muslims may be more vulnerable than other immigrant populations to radicalization. There is a danger, however, in advancing findings and making policies based on top-line results, a danger that many country or ethnic-identity based “Muslim” studies overlook: the possibility that top-line identities such as ethnicity (Uzbek or Kyrgyz) and religion (Islam) may not be the wellspring of support for violence, but rather, that other overlooked variables may be driving support for violence and terrorism.

An Alternative Explanation: Exposure to Political Violence

One variable of increasing focus in the terrorism literature is the effect exposure to political violence (EPV) has on attitudes toward militancy. Hirsch-Hoefler et al., for example, find in their study of the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine, that “under prolonged EPV, elevated levels of distress influence perceptions of threat, which in turn are associated with more intransigent and militant attitudes.” Not all Israelis and Palestinians have directly suffered as a result of violence. Those that have, however, are much more likely to support violence in pursuit of political objectives.

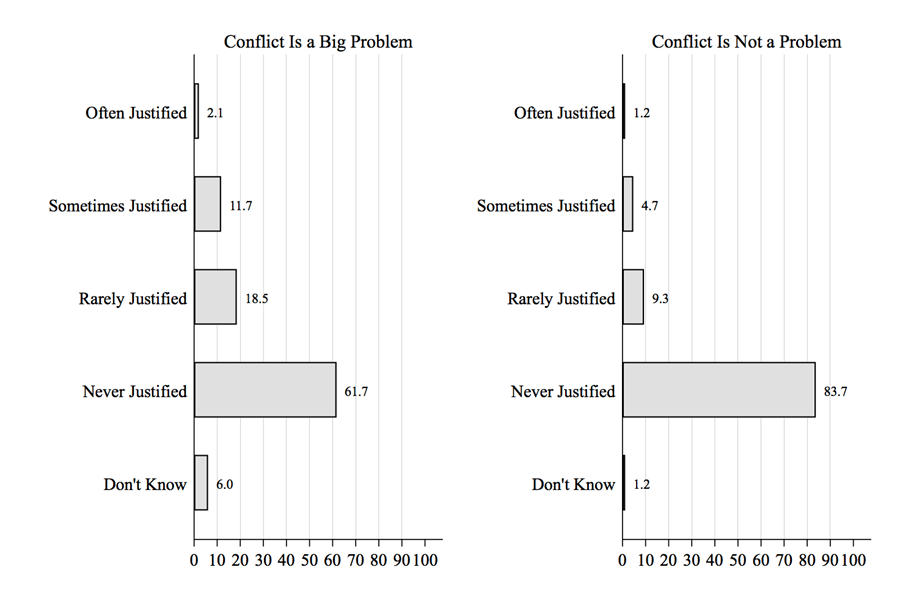

As Figure 2 illustrates, a similar relationship between conflict and support for violence in defense of religion exists among Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Russian language respondents in the 2012 Kyrgyzstan survey. For respondents who felt “conflict between ethnic groups was a major problem,” 62 percent agreed with the statement that violence was never justified in defense of religion. In contrast, for respondents who did not see conflict between ethnic groups as a problem, a considerably greater proportion—84 percent—reported that violence in defense of religion was never justified.

Figure 2. Percent Response: Violence Against Civilian Targets Is Justified in Order to Defend Islam from Its Enemies—by Perceptions of Ethnic Conflict (Pew 2012 Kyrgyzstan Survey)

Kyrgyzstan has endured multiple violent traumas. Riots between ethnic Kyrgyz and ethnic Uzbeks in southern Kyrgyzstan in June 1990 left more than 300 people dead. A second wave of deadly ethnic violence in June 2010 resulted in the deaths of at least 356 civilians and the razing of entire neighborhoods in the southern Kyrgyz cities of Osh and Jalal-Abad. Moreover, in the wake of the 2010 clashes, hundreds of young men were detained. Of these detentions, Human Rights Watch has documented sixty cases of “torture and ill-treatment,” for which the rights organization has either photographic evidence or first-hand accounts of “prolonged, severe beatings with rubber truncheons or rifle butts, punching, and kicking… [and] suffocation with gas masks or plastic bags.”

Vetting Extreme Vetting

We still know comparatively little about the ethnic Uzbek who killed eight people in New York City on October 31, 2017. We know Saipov’s family in the Uzbek capital, Tashkent, is comparatively wealthy and that Saipov enjoyed an elite education in Uzbekistan. We do not know, however, if Saipov or any of his family members were directly exposed to ethnic conflict or political violence—this is a topic that neither the repressive Uzbek regime nor, understandably, Saipov’s family in Uzbekistan, are keen to address. Nevertheless, the preceding analysis suggests that we cannot discount claims that exposure to conflict and violence in Central Asia may alter individuals’ perceptions of violence in defense of religion. These altered perceptions, in turn, may increase the likelihood that a small subset of Central Asians abroad will commit terror. Saipov, Akilov, and Masharipov may indeed have radicalized abroad. This radicalization abroad, though, may have been enabled by past exposure to conflict and violence when they were living in Central Asia.

Extreme vetting, even banning some groups from entering the United States, might have merit, but the categories the president and others advance for such vetting—Islam and ethnic/national identity—miss the mark. The most powerful predictors of support for militancy are not ascriptive categories of religion and ethnic identity, but rather, whether or not an individual has suffered as a result of past violence and conflict. The question for proponents of extreme vetting, then, is not whether the U.S. government should impose a travel ban on Muslims or a particular ethnic or national population, but instead, whether the U.S. government should bar from entry those who have directly experienced conflict in their home state. Such a policy would be an injustice. No less an injustice, however, are extreme vetting and travel ban discourses that see all Muslims and entire country populations as potential militants.

Eric McGlinchey is an Associate Professor in the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.

[PDF]