Since July of last year, about 40,000 inmates have joined the private Russian military company Wagner Group to fight on the front lines. The head of Wagner, Yevgeny Prigozhin, explained that bringing killers to the front line is justified because they are “more psychologically and morally prepared” than regular soldiers and that a murderer fighting on the battlefield is “worth three or four dandelion boys.”

In mid-January of this year, Ukrainian presidential advisor Mykhailo Podolyak said that “77 percent of the 38,244 Russian prisoners brought to fight in Ukraine have been killed, wounded, captured, or have gone missing.” The Mediazone project confirms at least 1,849 inmate deaths from February 22, 2022, to March 9, 2023 (11 percent of Russian casualties in Ukraine). Russia’s penal colony population did indeed decrease by 32,890 (from 465,896) last year, the largest drop in more than a decade. No official reasons were given for the sharp decline, which coincided with the beginning of Wagner’s prison recruitment push. Historical parallels are striking. Convicts replenished the ranks of the Red Army when the Soviet Union released more than a million prisoners from Gulag camps to fill battle lines in World War II.[1]

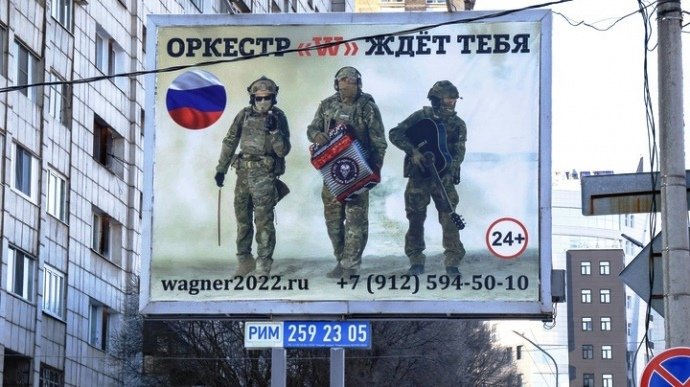

Today, Russian criminal law does not provide amnesty or parole for prisoners for participating in a “military operation.” The state parliament (Duma) has prepared several bills to rectify the situation, but only one has passed so far, which exempts fighters from criminal liability in the Donbas region. The overall scheme raises questions about the treatment and rehabilitation of prisoners and what happens when dangerous criminals walk free. In early February, Prigozhin indicated that the recruitment of prisoners has wholly stopped; however, the obligations undertaken by Wagner are still being fulfilled, and more recruitment centers—up to 58—have opened across Russia.

Once In a Lifetime Opportunity?

Olga Romanova, director of “Russia Behind Bars,” said that prisoners who agree to sign six-month contracts with Wagner are paid $3,000 a month. In the event of their death, their relatives may receive $70,000. However, their main motive is to become free. Convicts are promised a full pardon and release at the end of their contract. However, “presidential decrees on the pardoning of recruited prisoners are classified,” spokesman Dmitry Peskov said. Therefore, most often, the names and numbers of those recruited can be found out only after their death. Sources of information are usually regional media and “Wagner cemeteries,” such as in the village of Bakinskaya (Krasnodar region), where, as of early February, about 300 people were buried.

Most of the enlisted men were serving time for petty crimes like drugs, burglary, robbery, and theft. But court records of some recruits show they had been convicted for especially serious crimes, such as contract murders, grievous bodily harm, extortions, creation of a gang (banditry), and organization of a criminal association (see Figure 1). Parole for such crimes can be applied only after a prisoner has served at least two-thirds or three-fourths of his sentence. When considering parole, the court takes into account the behavior of the prisoner, attitude toward work, existing commendations and penalties, views toward the offense, compensation for the harm caused, and administrative opinions on the advisability of early release.

Figure 1. Number of People Sentenced for Banditry, Organizing a Criminal Community, and Occupying a High Position in the Criminal Hierarchy (2017-2022)

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | First six months of 2022 | |

| Article 209 (Banditry) | 88 | 79 | 64 | 51 | 64 | 35 |

| Article 210 (Criminal Community) | 133 | 122 | 66 | 107 | 63 | 54 |

| Article 210.1 (High Position) | – | – | 0 | 0 | 8 | 7 |

| Total Sentenced to Imprisonment | 197,537 | 187,794 | 172,914 | 147,484 | 156,778 | 79,076 |

Notorious criminal bosses serving life imprisonment can be released early if they have served at least 25 years, not committed violations for three straight years, and only by court consideration. Most of them are the leaders of regional organized crime groups, who have been convicted for serious crimes (murder-for-hire, armed robberies, extortions, and kidnappings) committed in the 1990s or 2000s. They could not be released easily, so expectedly, many sought to take advantage of the war for an unexpected early release. For example, the leader of the Orekhovo gang, Sergei Butorin, who was sentenced to life in prison for contract murders, once had a military profession and openly expressed his desire to participate in the hostilities in Ukraine.

Among the dangerous prisoners recruited by Wagner—and killed on the frontlines—were several well-known mobsters. For instance, gone is the leader of the Altai criminal association, Sherali Khatamov, who was sentenced to 16 years for extortion, as well as Igor Kusk, boss of the Kuskovskaya criminal group, and Sergey Maksimenko, head of the Penza criminal group “Olimpiya,” who were serving over 20-year sentences.

Last August, Russian President Vladimir Putin posthumously awarded a Medal of Valor to Ivan Neparatov, who was recruited by Wagner and was serving a 25-year sentence for five murders, three robberies, kidnapping, extortion, and other crimes committed by his organized crime group in Sergiev Posad (Moscow Region). However, not all powerful leaders of the Russian criminal underworld have been ready to change their beliefs or go against the informal criminal rules. At last year’s “brotherhood of thieves in law” gathering in Dubai, UAE, the Ukrainian conflict was discussed, and participants were reminded that their informal rules forbid cooperation with the government—Ukrainian or Russian—in any way, for any reason.

The Wagner Group’s Legal Status and Activities

Private military companies in Russia are still not regulated at the legislative level. A long time ago, in April 2012, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin talked about legalizing private military companies (PMCs), saying that such entities may be effective tools for realizing national interests without the direct participation of the state. Since then, parliamentarians have repeatedly tried to bring such organizations (like Wagner) out of the shadows into the legal field, but they all failed.

In March 2018, the government indicated that the latest draft law on the matter contradicts the Russian Constitution, in particular Article 13-5, which prohibits “the creation and activities of public associations, the goals and actions of which are aimed at creating armed formations.” It also goes against Article 71, according to which issues of foreign policy and international relations, war and peace, and defense and security, are the exclusive jurisdiction of the state. This bill was not supported by the Ministry of Defense, Federal Security Service (FSB), Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), Federal Protective Service (FSO), and the General Prosecutor. Adding to the difficulty, PMCs were not allowed to be called “volunteer formations.” This changed in October-November 2022, when the president approved a new law (419-FZ) allowing them to:

perform certain tasks in the field of defense; volunteer formations are involved that contribute to the fulfillment of the tasks assigned to the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation during the period of mobilization, in wartime, in the event of armed conflicts, in the conduct of counter-terrorist operations, as well as when using the Armed Forces outside the territory of the Russian Federation (hereinafter referred to as volunteer formations).

Wagner is led by oligarch Yevgeniy Prigozhin, a Putin crony and the target of multiple U.S. and foreign sanctions. On January 26, 2023, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) redesignated Wagner as a “Significant Transnational Criminal Organization” for its illicit activities in Ukraine, the Central African Republic, and Mali. Functionally, the January sanctions do not impose new restrictions beyond those already in place since 2017, when it was sanctioned for its activities in Ukraine, or November 15, 2022, when it was sanctioned again.

The Wagner Group is also on the Treasury Department’s list of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (“SDN List”). U.S. citizens are prohibited from dealing directly or indirectly with SDNs, and non-U.S. citizens can be held liable for “causing” violations by U.S. persons involving transactions with SDNs and can also be subject to secondary sanctions risks (which include, in particular, the risk of designation as an SDN themselves) for providing “material support” to SDNs.

From a formal point of view, the activities of Wagner fall under Article 208-1 of the Criminal Code that prohibits the creation of armed formations in Russia. Theoretically, those in head of Wagner should be punishable by fines up to 500,000 rubles ($7,000) and imprisonment up to 20 years. This should all be the case because Wagner’s activities contradict the interests of Russia, although some amendments were made in July 2022 (with text saying that some “shall be exempted from criminal liability if he, by voluntary and timely notification to the authorities or otherwise contributed to the prevention of further damage to the interests of the Russian Federation”). It is certainly note worthy that, according to paragraph 25 of the National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation (2021), a national priority is saving the people, developing human potential, and improving the quality of life and welfare of citizens. The participation of prisoners in an illegal armed group, at home or abroad, cannot be justified by national interests.

Legal Aspects of Prisoners Participating in a Military Operation

Russian criminal law does not provide for amnesty or parole for prisoners due to participation in a military operation. The Russian Federal Penitentiary Service has not answered inquiries about prisoners serving sentences for serious crimes and going to the front lines with Wagner. The service has not responded to relatives, whom it is obliged to notify about the movements of prisoners.

To date, pardons have been granted to convicts participating in the invasion of Ukraine. The right to pardon convicts belongs to the president only, and both Russians and foreigners can be pardoned. Article 85 of the Criminal Code determines that a pardon is possible in relation to an “individually defined person.” A pardon means the convict has his or her sentence reduced or replaced by a milder one or can be released completely. Before the Ukrainian events, Putin was not generous in pardoning prisoners: for 2017-2021, he pardoned only 23 convicts.

Without waiting for the adoption of federal law on this issue, Bashkir parliamentarians prepared and submitted their own bill. The idea was to attract prisoners on a more legal foundation. Chairman Konstantin Tolkachev said, “By participating in hostilities in defense of the interests of the Russian Federation, the convict will be able to atone for his guilt before society and thus achieve the goals of criminal punishment.” According to the bill, consent to participate in hostilities must be voluntary; prisoners who take part in military operations will be given a reprieve from punishment, and each day of their participation will be counted as ten days of imprisonment.

A somewhat parallel bill was also prepared by the Federation Council. According to it, if a prisoner shows courage and heroism while on military duty, he has been “corrected,” and a court may end the sentence and remove the criminal record. However, if a prisoner joins but then refuses to take part in hostilities, does not perform duties, or evades them, the court, on the proposal of the military command and with the opinion of the prosecutor, may revoke the deferment and send the prisoner back to jail. In the latest legislative development, the State Duma approved a draft bill that would make it a criminal offense to “public discredit” anyone—including volunteers and mercenaries—fighting for Russia. Such a crime should be punishable by imprisonment of five to seven years (Article 280.3).

Across Russian society, the main—justified—criticism is allowing criminals, many unpredictable and some with mental health problems out free. For example, in December, Wagner fighter (and deserter) Pavel Nikolin was arrested for a shooting in the Rostov region. He was recruited from the Ufa penal colony only the month before, where he had been for robbery and theft. Now, Nikolin is charged with “encroachment on the life of a law enforcement officer” and “illegal trafficking in firearms.”He had fired a Kalashnikov machine gun at a group of police officers, wounding one of them. Also, the existing corruption risks cannot be ruled out when dangerous criminals can be released for bribes. Every year, dozens of heads and staff of correctional facilities, who provide various illicit services to prisoners in exchange for bribes, are prosecuted across the country. Some of them assisted convicts on parole.

Conclusions

Putin’s decision to allow the Wagner Group to recruit prisoners in support of his flagging war marks a watershed in his 23-year rule. The policy circumvents Russian legislation and, by returning some brutal criminals to their homes with pardons, risks triggering greater violence throughout society. Over 60 percent of all investigated crimes are committed by previously convicted persons. A quarter of their crimes are serious, including murders, burglary, robbery, and bodily harm.

Because their deaths are less likely to fuel unrest, convict soldiers have found themselves used as “cannon fodder” at the frontlines. They have been deployed on the most perilous reconnaissance missions to locate Ukrainian positions and into head-on assaults, entailing heavy losses. However, federal authorities apparently forgot that the main goals of the penitentiary system (as is written until 2030) are ensuring the rights of persons held in correctional facilities and providing humane conditions in accordance with both Russian legislation and international standards.

In March, the UN “Working Group on the use of mercenaries” became alarmed by the recruitment of Russian and foreign convicts by the Wagner group. They received reports of pressure tactics by Wagner recruiters, lack of communication with families and lawyers, threats and ill-treatment by superiors, and executions for escape attempts. “Such tactics constitute human rights violations and may amount to war crimes,” the UN experts said. Some Ukrainians from the besieged areas may also have been victims of crimes by Russian-recruited prisoners, with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) estimating that at least 8,006 civilians (men, women, and children) have been killed in Ukraine over the past 12 months.

[1] According to the NKVD of the USSR, at the beginning of World War II, 2,290,845 prisoners were in labor camps. By January 1, 1945, the numbers had decreased by 63.7 percent (1,460,677 people).

Alexander N. Sukharenko is Director of the Center for the Study of New Challenges and Threats to the Russian Federation, Vladivostok, Russia.