The 2022 Russian war against Ukraine elicited worldwide indignation. Wealthy democratic countries levied harsh sanctions on the Russian economy and provided humanitarian and military support to Kyiv. Muted behind the loud condemnation of war by the leaders of G7, EU, and NATO has been a sizable group of nations that are yet to show strong support for Ukraine or reprimand the Kremlin. From Nigeria and Senegal in Africa to India, Indonesia, and Vietnam in Asia and Peru, Educator, and Honduras in Latin America, scores of governments have been reluctant to call Russia the aggressor and unwilling to take sides in the war.

These cracks in the united front against the Russian war have received little attention. When acknowledged, these diverging positions have been attributed to the vagaries of domestic politics or the so-called “Southern” dimension defined by these countries’ colonial past or, in the case of the African nations, a non-alignment posture. This memo demonstrates how Russia’s arms sales, foreign aid, and information propaganda have also affected countries’ positions on Moscow’s war in Ukraine. It concludes that the growing hesitancy of the West to commit its resources to certain countries and regions, coupled with lagging anti-Western sentiments informed by past American and European foreign policies, have allowed Moscow to spread its influence abroad.

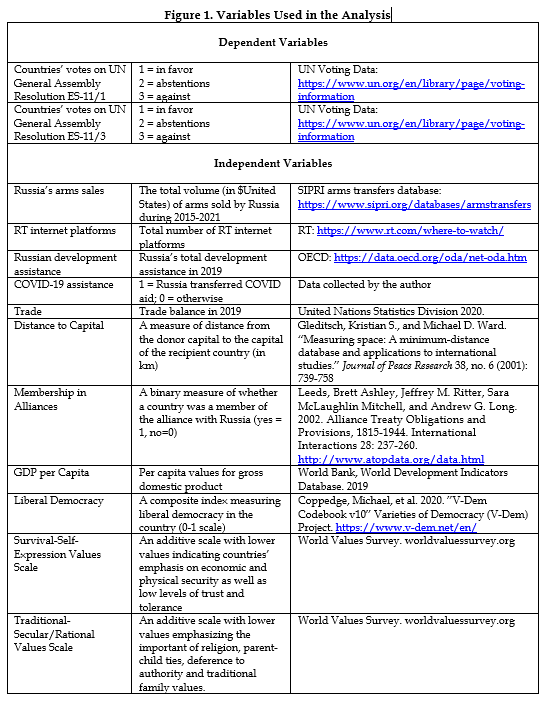

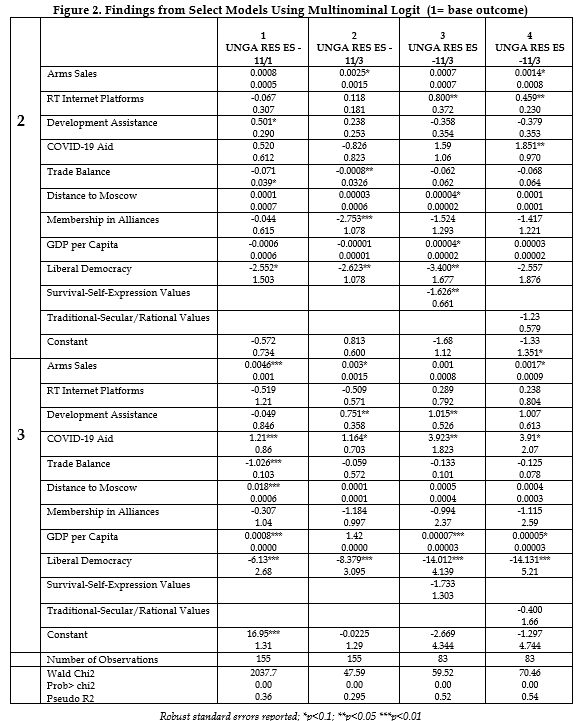

Using the roll call votes for UN General Assembly Resolution ES-11/1 (March 2, 2022) and UN General Assembly Resolution ES-11/3 (April 7, 2022), I conducted a statistical analysis of the effectiveness of limited economic, security, and informational resources deployed by Russia in its effort to win global hearts and minds (see Appendix A). Five countries, including Russia, voted against the first UN resolution condemning Russia’s war in Ukraine, and 35 countries abstained. Twenty-four countries voted against the second resolution suspending Russia from the UN Human Rights Council over its conduct in Ukraine, while 58 states abstained from voting.

Arms Sales Influence

Russia has been the world’s second-largest arms supplier (behind the United States), accounting for nearly 20 percent of global arms sales since 2016. Despite the Western sanctions imposed on Russia in the wake of the Crimea annexation, Moscow continued exporting arms and weapons systems to over 45 countries. For the Kremlin, arms sales have served three primary goals. First, they have provided an influx of capital into Russia’s ailing economy. Second, arms sales have been essential to Russia’s image as a great power state. And third, arms exports were an important conduit for Russia’s influence over client nations. The Kremlin has had some success in achieving the latter goal. Per my analysis of countries’ positions on Russia’s war in Ukraine, states that imported arms from Russia in the years preceding the 2022 war in Ukraine were also considerably more likely to either abstain from voting in favor of the UN resolutions condemning Russia’s aggression and suspending it from the UN Human Rights Council or voted against these resolutions.

Although Western sanctions curtailed Russia’s arms sales by 22 percent between 2016 and 2020, Moscow has sought to expand its arms markets in Southeast Asia and Africa while maintaining some of its long-standing arms relationships in this region. It became the number one arms exporter in Southeast Asia, delivering almost $11 billion, or 26 percent of the region’s weapons between 2000 and 2021. Vietnam, Myanmar, Malaysia, and Indonesia—all of which abstained or voted against the UN General Assembly Resolution ES-11/3—have been among the largest importers of Russian arms. Further, in the Indo-Pacific region, India, which abstained from voting on both UN resolutions, remains the largest purchaser of Russian missile systems and military equipment. And, in Africa, Moscow has brokered military sales deals with 20 countries since 2017. In 2021, for example, Russia signed military cooperation agreements with Nigeria, which abstained from voting on the UN General Assembly Resolution ES-11/3, and Ethiopia, which skipped the vote on the UN Resolution ES-11/3 and voted against the second document.

Development and Humanitarian Assistance as Russia’s “Soft” Power Tools

Russia is rarely thought of as an “international donor” as its levels of development and humanitarian contributions pale in comparison to those of the United States and other traditional donors. In 2015, for example, when Russia’s assistance amounted to $1.2 billion, the highest annual contribution to development and humanitarian goals, the United States sought to allocate $20.1 billion across all development assistance and humanitarian accounts. Still, since 2007, Russia has made a concerted effort to increase aid allocations to countries in the Middle East, Africa, and East Asia to bolster its global image and increase its leverage over recipient states. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has specifically named his country’s participation in international aid programs as one of Russia’s “soft power” tools.

The COVID-19 pandemic and slow, inconsistent, and heavily politicized U.S. response to the rapidly spreading infectious disease provided the Kremlin with an opportunity to instrumentalize the use of scarce medical resources. Russia provided various types of medical supplies and equipment to nearly 40 countries in all parts of the world during the first year of the pandemic. And, while the combined bilateral and multilateral allocations by Russia toward the health crises dwarf American and Chinese COVID-19 assistance, the highly visible aid transfers accompanied by Russian propaganda deriding the United States for abdicating its global leadership contributed to a perception of Russia as a more reliable partner for countries in need. To heighten the spectacle of the largest aid deliveries by Russia, the Russian president or foreign minister would have a highly publicized phone conversation with a counterpart in a recipient state, followed by a swift delivery of the much-needed assistance.

These efforts seemed to pan out, at least in the short run. In my analysis, countries which were selected by Russia as the recipients of its COVID-19 assistance, as well as those which received development assistance from Russia in the years preceding its war in Ukraine, were among those who abstained or voted against the UN resolutions condemning and punishing Russia for its aggression.

Russian Propaganda and Disinformation Campaigns Meet Receptive Ears

Lacking many traditional elements of soft and hard power, Russia has relied on widespread propaganda and disinformation campaigns to bolster its global standing and ability to achieve diverse foreign policy goals. Abetted by social media and virtual reality, Russian operators have injected the global informational environment with false narratives and propaganda designed to roll back American influence, boost Russia’s image, or weaken NATO and the EU. Russia’s extensive ecosystem of informational influence includes Kremlin-sponsored proxy sites, “trolls” exploiting social cleavages through fake blogs and inflammatory comments, bots connected to Russian intelligence, and state-funded media outlets, like Sputnik and RT (Russia Today) disseminating Russian propaganda under the guise of conventional international media.

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, RT operated pay television and free-to-air channels in more than 100 countries providing content in Russian, English, Spanish, French, German, and Arabic. In recent years, RT has become a leading purveyor of disinformation and propaganda campaigns targeting audiences in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia.

Tapping anti-colonial and anti-Western sentiments, these campaigns sought to portray NATO as the aggressor and the United States as a global threat. By creating false equivalences between the United States and European foreign policies and those of Russia, Moscow’s narratives have fostered disillusion, apathy, cynicism, and the deniability of the Kremlin’s own actions.

While the exact viewership of RT is difficult to establish, research has shown that its content has been widely shared on Twitter, YouTube, and social media, which amplifies the Russian narratives. It is not surprising, therefore, that the countries with greater numbers of RT satellite providers and operators were also more likely to abstain or vote against the UN resolutions condemning Russia’s war in Ukraine and calling for suspending Russia’s membership in the UN Human Rights Council.

The impact of RT has been more pronounced in countries that score lower on the survival/self-expression and traditional-secular/rational values scale developed by the World Values Survey project. Survival values indicate nations’ greater concern with physical and economic security as well as lower levels of trust and tolerance. Traditional values scores convey countries’ embrace of traditional family values and deference to authority, among other things. In the analyses, which included both values scales among predictors, countries with lower scores on the survival/self-expression and traditional-secular/rational values scales were also less likely to vote in support of the UN resolutions condemning and punishing Russia’s war in Ukraine. Where the United States and European countries have been quick to criticize Russia for its policies, the Kremlin’s brand of authoritarian politics and appeals to security, order, and traditional values find appeal in many countries across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

In the wake of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, all EU countries, as well as Canada, formally banned RT, and social media platforms in Europe restricted access to RT’s content. Yet, the content thrives outside the United States and Europe on Twitter, social media, and the Internet, including new websites disguising the banned Russian news media outlets. Together with the RT broadcasts, in which falsehoods proliferate on social media, these outlets breed Russia’s misinformation about the war in Ukraine and reinforce the pre-war themes of racism, colonialism, economic expansionism, and Washington’s hypocrisy. In fact, RT has been among the most retweeted platforms for tweets in Africa and Latin America since the beginning of the war.

Lessons Learned

Despite the considerable economic and human toll of war on Russia and its increasing isolation on the global stage, Moscow continues using its arms sales and military deals as well as informational and political levers in the countries that have been receptive to Russian influence for a host of reasons, ranging from shared anti-Western sentiment to national security priorities and cultural traditions. Punishing struggling nations for their links to Russia through secondary sanctions or reductions in development assistance and humanitarian aid is unlikely to change their governments’ behavior. On the country, it may play in the hands of countries like Russia and China while furthering the suffering of populations severely affected by rising energy and food prices. Pushing these countries deeper into social and economic emergencies may bode future security crises necessitating the involvement of the United States and its Western partners, who often rely on these same governments for addressing regional security concerns.

Western efforts at countering Russian propaganda and disinformation have worked well in the European context but have so far done little to galvanize public outrage with Moscow in locations that have long harbored anti-Western sentiment. While the United States and EU governments should continue tracking, confronting, and rebutting Russian disinformation, they should also listen to legitimate concerns and acknowledge uncomfortable truths about significant differences in the volume and types of assistance provided to peoples around the world experiencing acute crises and emergencies. If global unity is a genuine concern for the West, both Washington and Brussels should devise more circumspect, long-term, comprehensive, and diversified approaches to countries caught in the midst of the broader conflict between Russia and the West to pay close attention to factors that have enabled Moscow’s influence.

Appendix A

Mariya Omelicheva is Professor of National Security Strategy at the National War College, National Defense University. The views expressed in this memo are those of the author and do not represent an official position of the U.S. Government, Department of Defense, or National Defense University.