At the Valdai conference in October 2022, President Vladimir Putin once again claimed that “Ukrainians and Russians are one people.” This preposterous claim that he has repeated on numerous occasions has understandably elicited attempts from Ukrainians to refute it, but the arguments they have used have often been misconceived. For example, some use biological arguments as if identity is genetically coded, but more commonly, it is claimed that Ukrainians and Russians have radically different cultures and values. But national identities are not determined by any alleged common “cultural stuff” in the population; cultural differences within a nation may be just as large, or larger, than between nations.

Moreover, empirical data from the two nations show that they cannot be differentiated along cultural criteria. This line of argumentation also runs counter to what we know about how identities—and national identities—are formed. Groups contrast themselves to their neighbors, particularly those they feel threatened by and want to distance themselves from. The more Russians insist that a separate Ukrainian identity does not exist, the more important it becomes for Ukrainians to develop one. And the more this Ukrainian identity also acquires anti-Russian traits.

Identities and Values Are Different Things

In late July 2021, Putin devoted an entire article, ”On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,“ to the assertion that Ukrainians and Russians are “one people.” Shortly thereafter, the Ukrainian survey bureau Rating Group conducted an opinion poll in all Ukrainian regions except those not controlled by Kyiv. Respondents were asked to agree or disagree with the following statement: “Russians and Ukrainians are one nation and belong to the same historical and spiritual space.” Of the 2,500 persons asked, 41 percent agreed with the statement, and 55 percent disagreed.

Commentators pointed out that those pollsters had collapsed two statements into one—Russians and Ukrainians being “one nation” and “belonging to the same historical spiritual space.” The latter claim is less controversial than the former, and some Ukrainians have indicated that merging the two statements could have led to confusion. Even so, the resultant figure was remarkably high, and may well have been part of the reason why Putin and his advisors thought it would be a simple matter to remove the democratically elected leaders in Ukraine by invading the country. But how can these figures be explained?

Ukrainian researcher Larisa Tamilina has attempted to refute the claim that Ukrainians and Russians are one people by using data from the World Value Survey (WVS). She finds that the value orientations of the two peoples are radically different: “The desire for freedoms, liberal democracy, and an inclusive society are the main markers of the Ukrainian-Russian divide.” She points out that in the seventh wave of WVS, 42 percent of respondents in Russia declared that they had confidence in their parliament, as against only 19 percent of Ukrainians who had confidence in theirs. These figures, however, cannot be used to prove differences in political culture in the two countries, as they measure attitudes toward different institutions.

It is at least theoretically possible that the Russian parliament performs better and therefore inspires more trust than the Ukrainian parliament (Verkhovna Rada). We can note, for instance, that responding to the same question in the WVS survey, Germans reported 44 percent trust in their parliament (Bundestag)— virtually the same share as the Russians’ trust in the Russian parliament (the Duma)—but it would be foolhardy to conclude on that basis that today’s Russian and German political cultures are identical. Moreover, Tamilina’s reading of the WVS data is selective, focusing on those questions where she found the largest discrepancy between Russian and Ukrainian values.

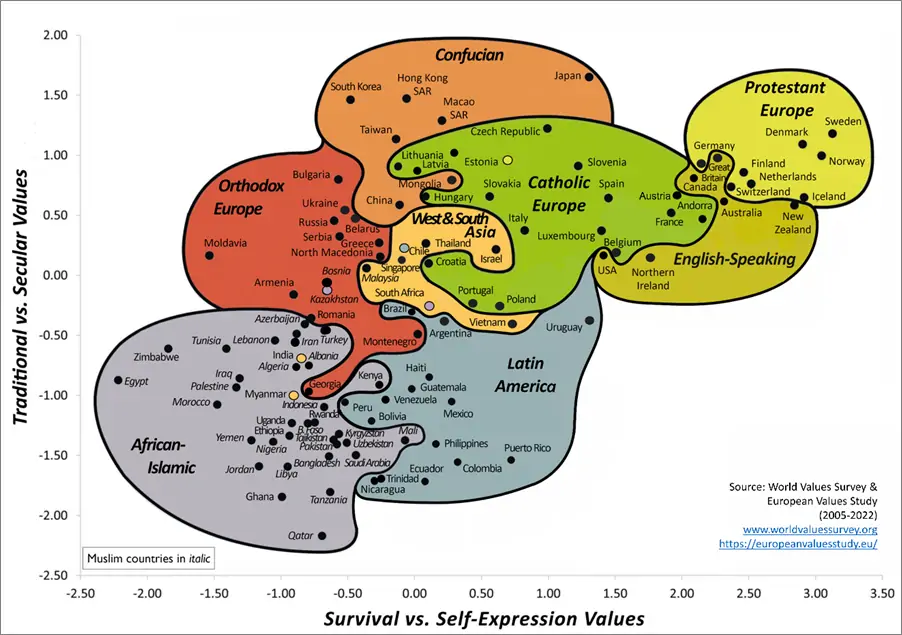

Combining their findings from all questions in all surveyed countries, the WVS team produced an aggregated value map in which Russia and Ukraine appear right next to each other—as the two countries with the most similar value profiles. See the red section labeled “Orthodox Europe” in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Proximity of Ukraine and Russia, Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural Map 2023

However, Putin is not right; it is a “category error” to stretch values across identities. As Canadian political philosopher Will Kymlicka has noted, the fact that two national groups share the same values or principles of justice does not necessarily give them any strong reason to join (or remain) together.

To underpin his argument, Kymlicka pointed to identity development among Francophones in his own country. For a long while, they had a rather different culture than the Anglophones, rooted in strong adherence to the Catholic faith, traditional family structures, and a generally conservative outlook on life. At this stage, they did not have any strong sense of being a separate “nation.” In the postwar period, however, the Canadian Francophones found themselves caught up in the vortex of modernization; they acquired increasingly secular and liberal values, which brought them closer and closer to the rest of the Canadian population. And yet, precisely at that time, they began to develop a collective identity as a separate national group within Canadian society, resulting in a drive for the establishment of a separate, independent state of Quebec.

The crystallization of national identities does not hinge on any unity of values; indeed, trajectories of values and identities may move in opposite directions. This has direct relevance to how we can understand Ukrainian identity development today.

The Role of “the Other” in Identity Formation

What, then, determines identity formation if it is not values? Here the writings of Norwegian social anthropologist Fredrik Barth offer important insights. In 1969, he wrote an article that fundamentally changed our understanding of how ethnic groups and social identities are constituted. The common-culture approach, he argued, implicitly ignored cultural differences within groups, made it difficult to explain cultural change, and did not sufficiently allow for cultural overlap and continuity between and among groups. Barth saw the boundary between groups as the locus of identity formation and differentiation. As a social anthropologist, he focused on the role of boundary markers or “diacritica” in relations between ethnic groups. Later scholars have expanded this approach to include, among other things, the study of nationalism.

According to Barth and his disciples, it is in the contrast and interaction with outsiders, with “the Other,” that group identity is constructed and maintained. Indeed, without such interaction, identity formation would hardly take place at all. As Barth’s younger colleague Thomas Hylland Eriksen expressed, “If the setting is wholly mono-ethnic, there is effectively no ethnicity, since there is nobody there to communicate cultural difference to.” All groups have numerous neighbors, and therefore they have many potential candidates for an “other” to develop their identity in relation to.

However, political scientist and anthropologist Iver Neumann has convincingly argued that the group you want to distance yourself from is far more important in this respect than those you want to emulate. Opposition rather than mimicry determines identity formation. This “Other with uppercase O” Neumann called the Constituting Other. In Tsarist Russia, in the USSR, and in today’s situation, the Russians play that role for the Ukrainians.

Boundary construction and maintenance are a question of power relations and hence of politics. Stronger groups (larger, with more material resources and with a robust self-awareness) tend to de-emphasize their identity distance from culturally similar neighboring groups, subsuming them under their own instead. Indeed, many Russians, historically and today, regard Ukrainians and Belarusians as mere subgroups of a larger “Russian” nation. The members of the weaker cultural group may accept the invitation to become a part of the larger community—but this invitation may also be perceived as an intolerable encroachment of their integrity, an attempt to obliterate their very “self.”

Weaker and smaller groups, and groups with an unclear or fragile collective identity, often attempt to distinguish themselves as much as possible from stronger, overweening neighbors. According to one Ukrainian identity discourse, Russians are not even Slavs: the Russian language is allegedly a mixture of Finno-Ugric and Tatar languages “in which the Slavic admixture is insignificant.” But, as we have seen, far from all Ukrainians subscribe to this discourse. Less than two years ago, more than 40 percent of Ukrainians regarded their nation as intimately related to the Russian people and indeed part of “one people” together with it. The identity trajectory of smaller cultural groups in the orbit of a larger neighbor cannot be determined in advance, and the outcome may not be the same for all members of the group.

In a famed parable, British-Czech philosopher Ernest Gellner discussed what might happen when a smaller cultural group that he called “Ruritanians” inhabit a peripheral territory in a larger country called “Megalomania.” Ambitious “Ruritanians” who want to make a career on the national scene realize that they are handicapped by their poor command of the Megalomanian national language and cultural codes. They are confronted with a choice: either adapt to national standards so that they can pass as “genuine” Megalomanians, or decide that their Ruritanian homeland should be a separate nation-state in which the Ruritanian idiom could become the national high-culture language and they, as the national elite, could occupy the most prestigious positions.

In situations where the cultural distance between Ruritanian and Megalomanian culture and language is short, less effort is required for educated Ruritanians to switch to Megalomanian and the chances that they will go for assimilation increase. Applied to the Ukrainian case, we can conclude that this path was indeed open to the Ukrainian intelligentsia in both the 19th and 20th centuries. And if we allow ourselves to indulge in counterfactual reasoning, we may argue that, if political history had taken other turns, the Ukrainian territories could have become no less integrated parts of a Russian state than Provence is in France today. Ukrainians and Russians could have ended up as one nation, just as Hochdeutsch-speaking Catholic Bavarians and Plattdeutsch-speaking Protestants in the north today all see themselves as unquestionably German. Bavarians, of course, retain a strong sense of separate identity within the German nation, and so could the Ukrainians have done in the Russian nation. Why did that not happen? A comprehensive answer would require a separate, lengthy article, so I will limit myself to a few observations.

Firstly, the fact that the Soviet state system provided the Ukrainians with a separate proto-nation-state, the Ukrainian Union Republic, meant that if they opted for a separate identity, they would have a political unit to mobilize around.

Secondly, right up to World War II, a sizable group of Orthodox East Slavs resided outside the Russian state, initially in the Habsburg province of Galicia, and in the interwar period in Eastern Poland. In Austria-Hungary, they enjoyed a degree of freedom of speech and worship unthinkable in the Tsarist Empire and were able to develop their own cultural and strong sense of separate ethnic identity, distinct not only from the Germans but also from the Habsburg Poles.

When culturally related groups end up on different sides of political borders, they often develop separate identities, as happened with Austrians and Germans, and Dutch speakers in Belgium and the Netherlands. In the case of Orthodox East Slavs in Austria-Hungary, this happened in the Hungarian part of the Dual Monarchy in Transcarpathia. Here, they developed a collective identity as “Ruthenians,” the official Habsburg designation for this population. In the Austrian part of the country, after some vacillation, they concluded that they were “Ukrainians,” belonging to the same group as those in the Russian empire whom the Tsarist regime called “Malorossians”: they were all “Ukrainians.”

Thirdly, having first encouraged the development of a Ukrainian national identity within the Ukrainian Union Republic in the 1920s, the Stalinist regime in the 1930s decided to crush the very same Ukrainization policy that it had itself brought into being the previous decade and arrest those who had been in charge of it . In the 1930s, it also carried out the enforced collectivization of agriculture, which led to the death of millions of Ukrainian peasants. As a result, large sectors of the peasantry and the intellectuals in Ukraine were alienated from Soviet power. The 1932-33 Holomodor famine left an indelible trauma in the Ukrainian population and gave rise to a strong martyr identity, an enduring rallying point for Ukrainian nationalists. Even if their persecutors were “Soviet Communists” rather than “Russians”—and although many Ukrainian Communists also took part in the atrocities—this Ukrainian identity acquired a distinctly anti-Russian character.

However, the identity choice for Ukrainians was still not settled once and for all. After Stalin’s death, Ukrainians in the USSR were allowed to pursue careers not only in “their own” republic but also at the federal level of the Soviet Union, almost to the same degree as ethnic Russians. Virtually all Ukrainians were fluent Russian speakers, and increasing numbers of them switched to Russian as their first language. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the political authorities in Kiev (re-named Kyiv in 1995 in English) engaged in determined nation-building, but even as recently as 1996, there were solid grounds for calling Ukrainian nationalism “a minority faith,” as Andrew Wilson did. Four years later, Wilson remarked that ethnic identities in Ukraine were “still blurred.” And finally, in the summer of 2021, as noted, identity links between Ukrainians and their northern neighbors remained so strong that a sizable group of Ukrainians agreed that Ukrainians and Russians comprise “one people.”

Conclusion

The identity of a group cannot be established by any objective criteria and certainly not by any outside observers. The securest—indeed, the only—way to determine people’s national identity is to ask them whom they identify with. Among Ukrainians, as we have seen, there have historically been disagreements about their identity distance from Russians, which has continued to the present time. This dispute seems to be more firmly settled today than at any other time in Ukrainian history—as a result of the Russian attack. Thus, the thunder of the cannons in the Russian invasion sounded the death knell to a common Ukrainian-Russian identity. More than any other individual, Putin has contributed not only to the crystallization of a separate Ukrainian identity but also to the consolidation of a Ukrainian nation, which defines itself, first and foremost, as profoundly different from the Russians.

Pål Kolstø is Professor of Russian Studies, Central Europe, and the Balkans in the Department of Literature, Area Studies, and European Languages at the University of Oslo, Norway.