In the wake of Russia’s massive invasion of Ukraine beginning in February 2022, the Ukrainian economy unsurprisingly suffered a major shock. The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) fell by a staggering 29 percent in 2022. Since then, however, the Ukrainian state and its people have overcome enormous odds to achieve an extraordinary economic rebound, even as massive attacks by Russia continue. The World Bank estimates that Ukraine’s GDP rose by 4.8 percent in 2023, with an additional 3.2 percent growth forecast for 2024. Yet as encouraging as this might be, it remains a daunting task to restore Ukraine’s economy to anywhere near pre-war levels: some US $486 billion is already required for that effort, a figure that will only increase as additional damage is incurred in the course of the ongoing fighting.

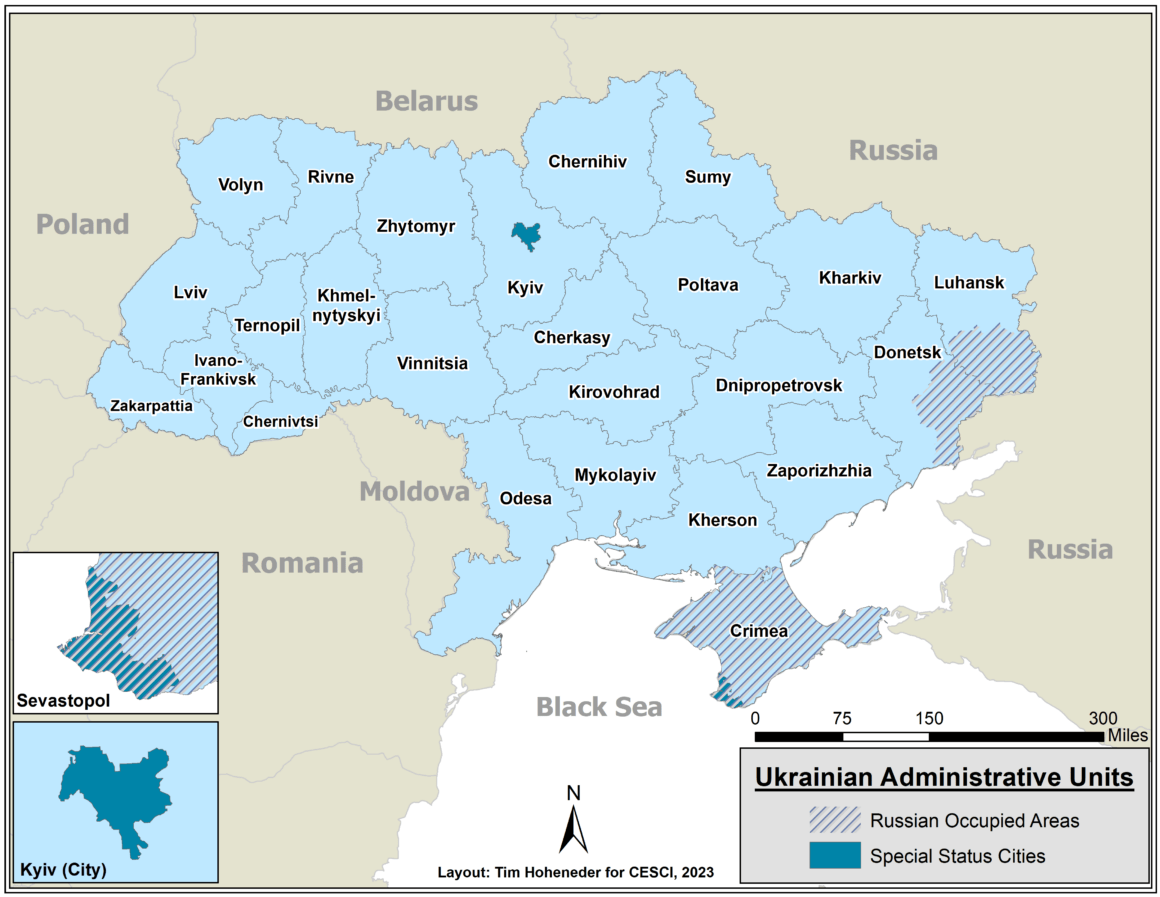

Given this outlook, our research makes two encouraging findings. First, available economic and investment data reveal that an ongoing major spatial realignment of production is playing a significant role in Ukraine’s economic rebound. Ukrainian enterprises and individual entrepreneurs have adjusted by shifting some production and client support away from the most vulnerable regions (see Figure 1) in southern and eastern Ukraine and toward strategically safer areas in the central and western parts of the country. New capital investment, both domestic and foreign, is likewise primarily being directed westward. Second, Ukrainian businesses have also proven quite adaptable to wartime conditions and have, in some cases, achieved at least partial success in restoring production in heavily affected areas, such that these areas may continue to play an important—if reduced—role in Ukraine’s post-war economy.

Figure 1. Regions of Ukraine as of 2022

Note: No data are available for the Crimean Autonomous Republic or the city of Sevastopol, both of which remain under Russian occupation as of this writing, and figures below for Donets’k and Luhans’k oblasts include only areas under Ukrainian government control.

Prelude to Recovery: The Regional Dimension

As we discussed in a previous PONARS memo, even before the initial Russian invasion in 2014, Ukraine’s economy was clearly realigning away from the east, where legacy and often outdated heavy industrial productive capacity was stagnating, toward the western and central regions of the country. As we explained, such spatial shifts are common in large countries with diverse regional natural and human resources. But after Russia’s illegal seizure of Crimea and a large part of the Donets’k and Luhans’k oblasts (collectively referred to as the Donbas) in 2014, the move away from the east accelerated. In a more recent memo and a related blog post, we (with Matthew Lantzy) described how, as the main Russian attacks unfolded after February 2022, some of the country’s most productive regions in the east and south suffered especially heavy damage, thereby increasing the relative importance of the center and west as the national economy constricted. The loss of valuable manufacturing capability also, of course, figured prominently in the sharp decline in GDP.

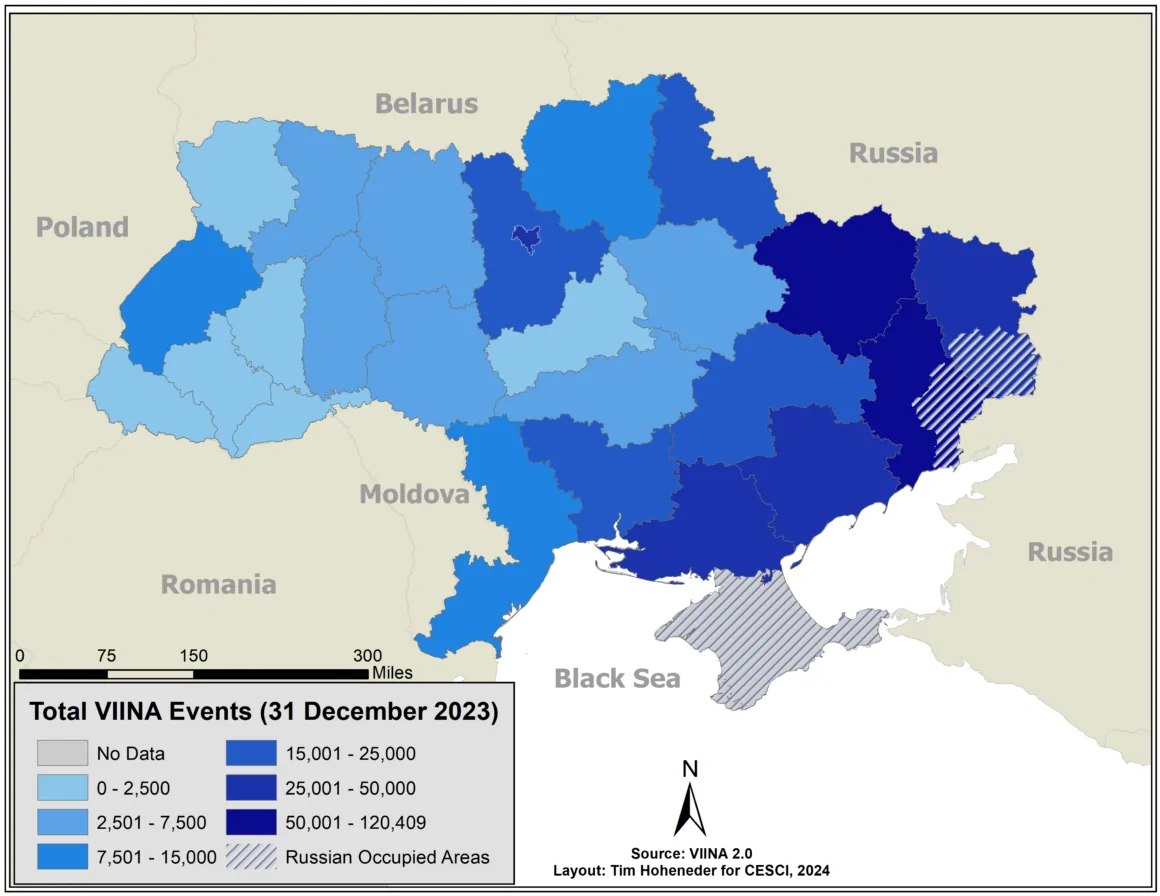

This spatial pattern of destruction due to Russian attacks is, as of December 31, 2023, clearly evident in data captured by the Violent Incident Information from News Articles (VIINA) project (see Figure 2). These events (i.e., missile, long-range artillery, and air attacks) very closely track earlier monetary estimates of material losses by oblast (Spearman’s rho = .888, N=25) conducted by the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE), so we are confident that regional economic impacts align closely with war damage. Other data compiled by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) show that within some heavily affected oblasts (e.g., Kherson, Mykolaiv, Luhans’k, Kharkiv, and Zaporizhzhya), destruction tends to be concentrated in specific areas, some of which have been retaken by Ukrainian forces, while other areas in the same oblast are relatively less affected. Further, as a cautionary note, some one-off events, such as the destruction of the Kakhovka dam in Kherson Oblast in June 2023 by Russian forces and the attacks on grain storage facilities in Odesa and other ports in 2023, have outsized importance in economic terms, making them difficult to assess as “events” per se. Finally, we do not intend to imply that the more isolated Russian strikes in relatively less-damaged regions are unimportant or not worthy of mention because they did not result in major economic disruption; all attacks against civilian populations—including in Vinnytsya in July 2022 and L’viv in July 2023—involve enormous human suffering and must be regarded as among the many war crimes committed by Russian forces in this conflict.

Figure 2. Total Violent Incidents by Oblast

The Economy Moves West

Detailed official data on economic activity for Ukraine by oblast after 2021 are, understandably, not publicly available. Further, as Ukraine’s economic recovery has progressed, the domestic defense industrial sector has, for obvious reasons, grown significantly, almost certainly outpacing non-defense expenditures. There is very limited place-specific information about these activities, and in the rare instances where locations of defense plants might be inferred, we have chosen to exclude them. It is also the case, of course, that many non-defense firms have reoriented their operations to supplying the military, but we are unable to parse those data. Finally, some key businesses involved in the war effort are by their very nature footloose and difficult to track because of their small footprint, especially the country’s IT sector and the highly dispersed production of the military drones that have allowed Ukraine’s armed forces to blunt and even reverse the territorial gains Russia made early in the war.

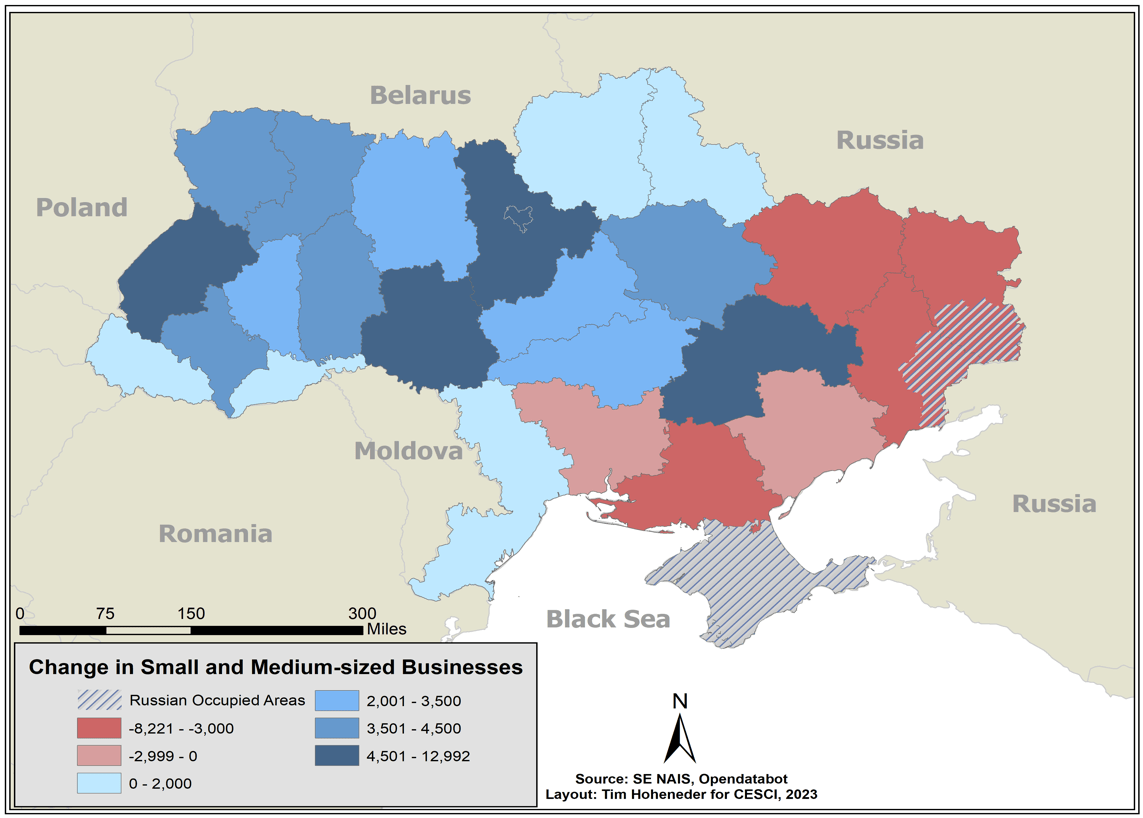

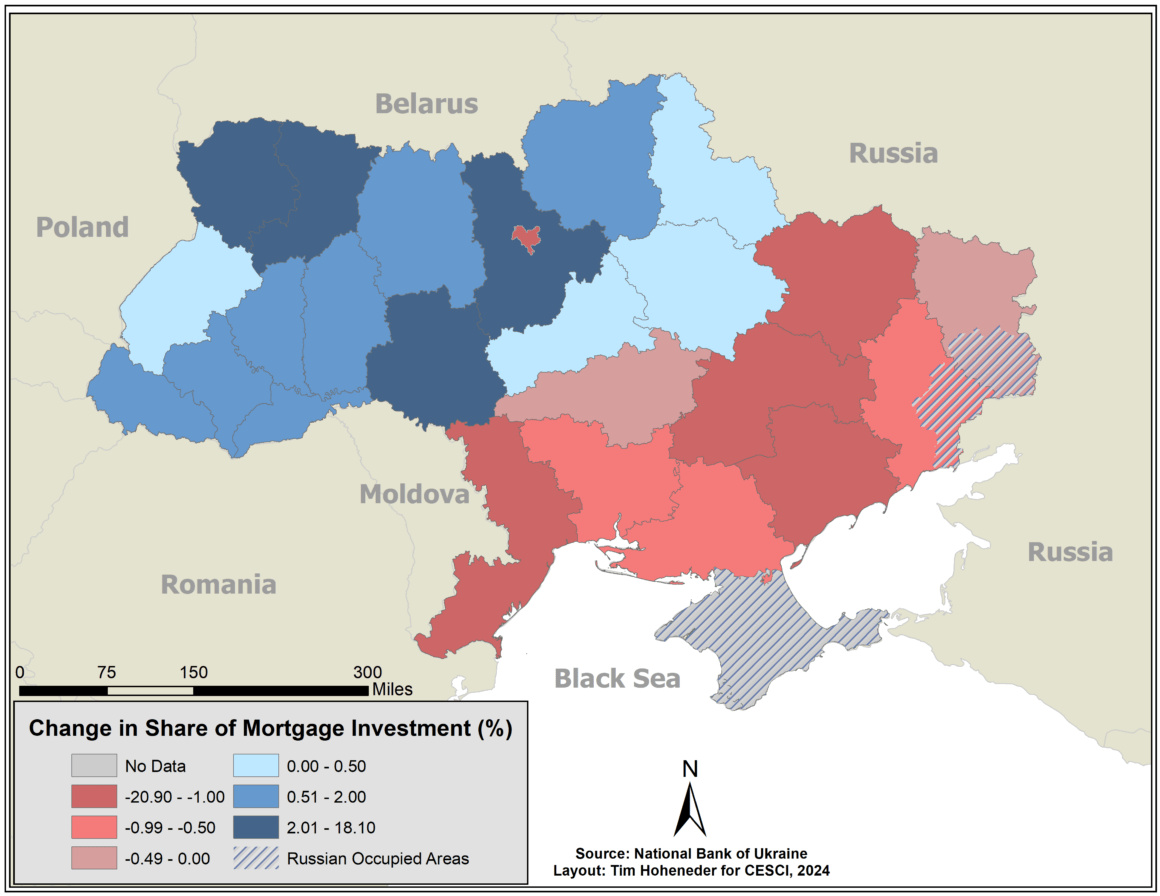

With these caveats in mind, we employ four datasets to describe the ongoing shifts in the spatial pattern of economic activity in Ukraine. First, we track net changes among the oblasts in business licensing using official figures for the net between new and closing small and medium-sized enterprises, or SMEs. Second, we consider changes in the numbers of individual entrepreneurs or sole proprietors (Ukrainian: fizichna osoba-pridpriyemets), or FOPs, across the country. Third, we compare changes in the share of national mortgage financing from 2021, the last full peacetime year, and 2023, the first full wartime calendar year, in each region. Finally, drawing on business news reporting, we compile notices of new and expanding projects in each oblast through 2023 that have drawn both domestic and foreign investment. While none of these measures are definitive in and of themselves, the combination of the four should be at least suggestive of evolving regional economies.

Data on new and lapsing SME business licenses (see Figure 3) suggest that the Ukrainian economy has indeed been shifting westward—away from areas adjacent to the battlefront—since the outbreak of the full-scale war in February 2022. L’viv, Vinnytsya, Kyiv, and Dnipropetrovsk oblasts and the city of Kyiv have experienced the largest increases, while Kharkiv, Kherson, Donets’k, Luhans’k, Zaporizhzhya, and Mykolaiv, the regions that have witnessed the most serious fighting (see Figure 2), have seen significant declines.

The regional distribution of new licenses for single-entrepreneur business ventures (FOPs) (see Figure 4) aligns very closely with the distribution of new licenses for SMEs (Spearman’s rho = .887, N=25), again suggesting that Ukraine’s economy has been reorienting westward. Dnipropetrovsk, L’viv, Odesa, and Kyiv oblasts and the city of Kyiv figure most prominently on the positive side, with Donets’k, Luhans’k, and Mykolaiv oblasts having fallen off the most dramatically.

Figure 3. Change in Registrations for SMEs through August 2023

Figure 4. Number of New FOPs through December 2023

The changing distribution of national mortgage funding by region between 2021 and 2023 (see Figure 5) again reflects the relative shifting of investment monies westward, with Volyn, Vinnytsya, and Kyiv oblasts garnering the largest increases and regions to the east, as well as the city of Kyiv, losing ground. New investment occurred in all regions—indeed, the national total actually increased during this period—but local market conditions (which varied from place to place) and, we suggest, perceptions of security and regional population change account for this particular trend.

Figure 5. Change in the Share of New Mortgage Investments, by Region, 2021 and 2023

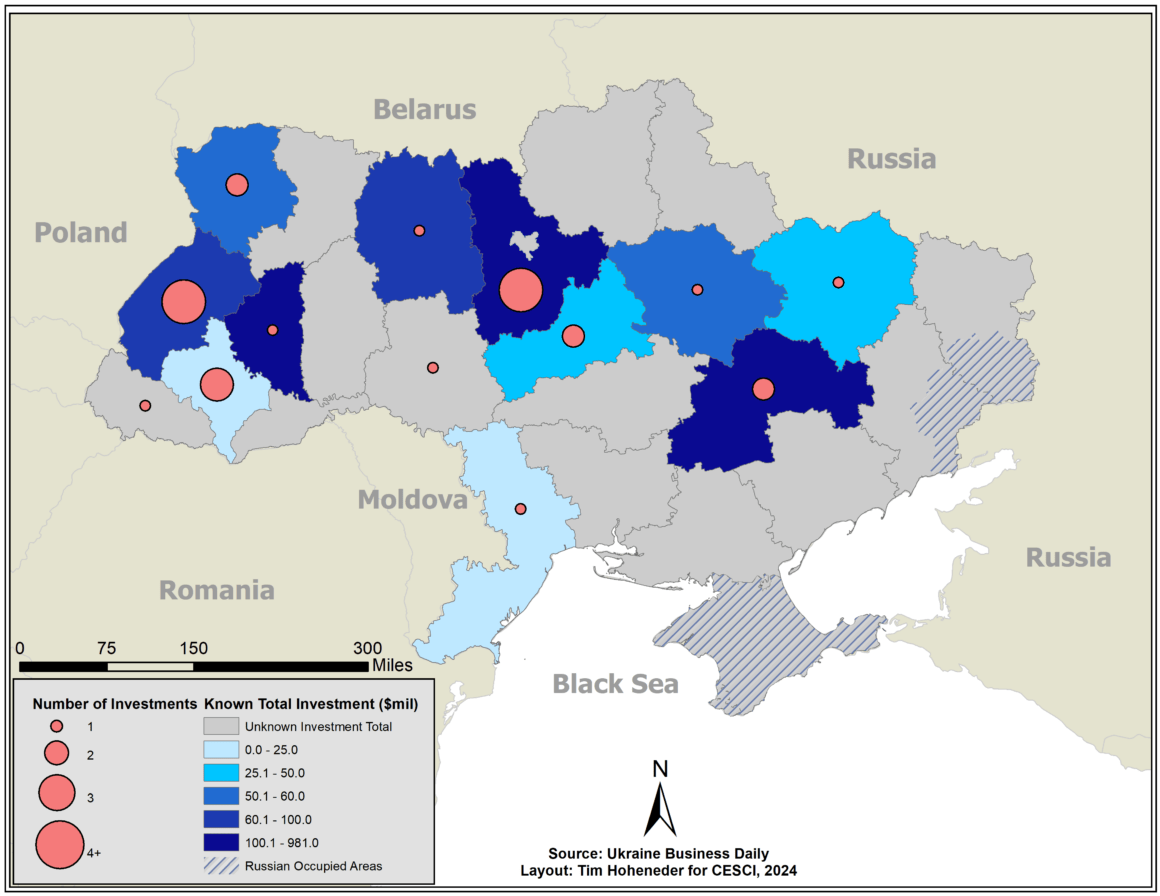

Finally, through searches of business news sources, we identified 32 specific capital investment projects carried out in Ukraine from March 1, 2022, through December 31, 2023. Despite our list being almost certainly incomplete, the general spatial pattern of the ventures of which we are aware (see Figure 6) is largely in keeping with the data on SMEs and FOPs, with the lion’s share of investments being made in the central and western regions. Specifically, L’viv, Kyiv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Dnipropetrovsk, Volyn, and Cherkasy oblasts lead in terms of the number of new projects, with Ternopil and Zhytomyr oblasts each garnering especially large single investments. Those regions closest to Russia and the fighting, meanwhile, have not been as attractive for investors.

Figure 6. Number and Value of Domestic and Foreign Investment Projects as of December 2023

Conclusion: Opportunities and Challenges of Regional Economic Changes in Ukraine

As we have shown, the available economic and investment data reveal that an ongoing major spatial realignment of production is playing a significant role in Ukraine’s economic rebound. Both entrepreneurial activities and capital investment have reoriented away from those regions closest to the front lines and toward strategically safer areas in the central and western parts of the country. In some cases, Ukrainian businesses have also achieved at least partial success in restoring production in heavily affected areas.

In terms of Ukraine’s sustainability going forward, the westward shift of the country’s economy to reduce the vulnerability of enterprises and take advantage of favorable locations for new investment implies both positive and problematic changes from the status quo antebellum. If the regional economic landscape was, as we have shown in our prior work, already tilting in that direction for reasons of efficiency and/or profitability, then these more recent wartime shifts are reinforcing a positive trend that portends more robust growth going forward—growth that, in turn, is vital to the country’s national security. These new and expanding businesses provide at least some opportunities for the some 3.7 million Ukrainians who have become internally displaced persons (IDPs); a recent report from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) indicated that 39 percent of IDPs have relocated twice—mainly to central and western regions such as Volyn, Vinnytsya, L’viv, Zhytomyr, Ivano-Frankivsk, and the city of Kyiv—to find employment and for security reasons. Clearly, forced in-migration presents an array of community-related problems that challenge local administrations and can generate negative feelings among established inhabitants. This has certainly been the case in wartime Ukraine. In the longer term, however, in-migration can provide the labor and skills required to expand enterprises. This simultaneously generates additional demand for local products, housing, education, and healthcare, all of which create additional need for workers as economic multipliers.

All this being said, there are compelling reasons for undertaking at least some major reconstruction projects and encouraging business development in the heavily damaged areas in the eastern and southern oblasts, and here questions of equity and political stability come to the fore. As we (with Cynthia Buckley) suggested before the current war commenced, the Ukrainian state has displayed a weak ability to deliver basic social services, fostering unfavorable attitudes toward the government and—at the extreme—challenges to state legitimacy. The aforementioned IOM study further found that vast numbers of people were internally displaced within their respective regions, especially in Kharkiv Oblast, which in 2021 ranked third among all oblasts in terms of its share of GDP. The physical and human capital that persists in such regions implies a strong case for rebuilding local economies, at least to some extent, as one aspect of a long-term national recovery plan that would enhance Ukraine’s socioeconomic capacity while taking into account the needs of all citizens.

Ralph Clem is Emeritus Professor of Geography and Senior Fellow in the Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs at Florida International University. Erik Herron is the Eberly Family Distinguished Professor of Political Science at West Virginia University. Timothy Hoheneder is a doctoral student at the University of New Hampshire. Khrystyna Pelchar is a graduate student at West Virginia University.