(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) How does U.S. policy toward Ukraine resonate with the Ukrainian public? What kind of policies in Washington make the most positive or negative impact, and why? Survey data from Ukraine indicate that Washington has considerable leverage in Ukraine’s society and a substantial reservoir of public goodwill. While stronger in Ukraine’s Western and central regions, approval of relations with the United States is the strongest among Ukrainians who view them as helping the country protect its sovereignty, collaborate with NATO, and develop an advanced and vibrant state. Fighting corruption and democracy promotion have no significant impact on U.S. policy assessment. The latter is consistently more negative among Ukrainians who get most of their news from Russia. Ukrainian views of the two U.S. presidents’ relations with President Vladimir Putin from 2015 to 2020 provide a robust indicator of U.S. foreign policy resonance—with President Donald Trump’s perceived sympathies for Putin likely keeping his ratings lower than his predecessor’s.

Ukraine’s Great Aspirations

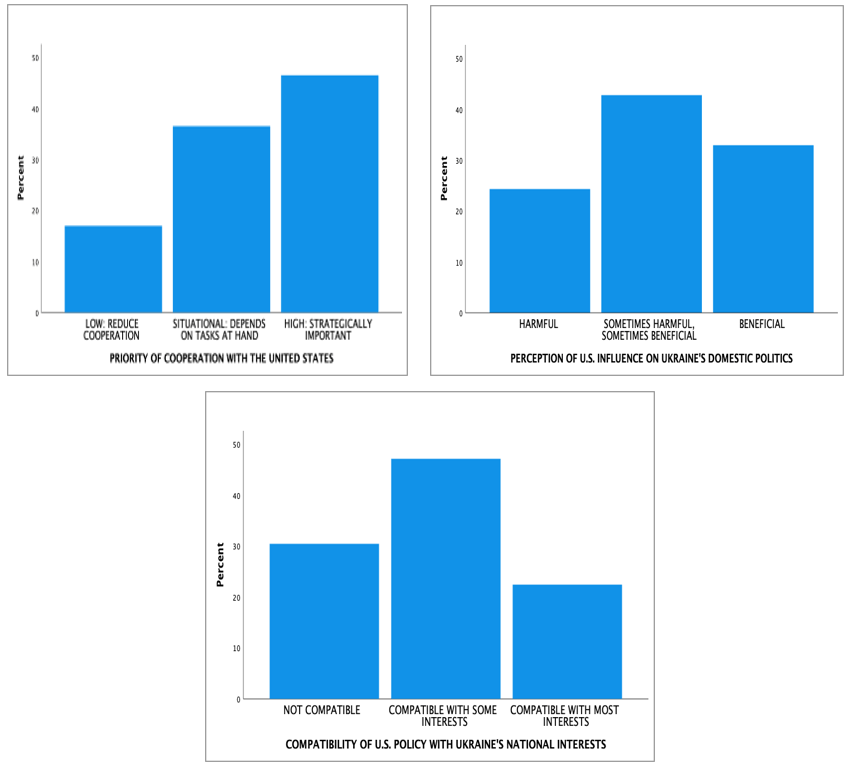

To begin with, the overwhelming majority of adult Ukrainians express positive views of their country’s relations with the United States. This is according to the annual nationwide survey conducted by the Institute of Sociology of Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences (UNASIS) exactly one year ago in October-November 2020 (N=1,800). A striking 83 percent of respondents said cooperation with the United States was a priority for Ukraine, with close to half of all respondents considering it strategically vital.

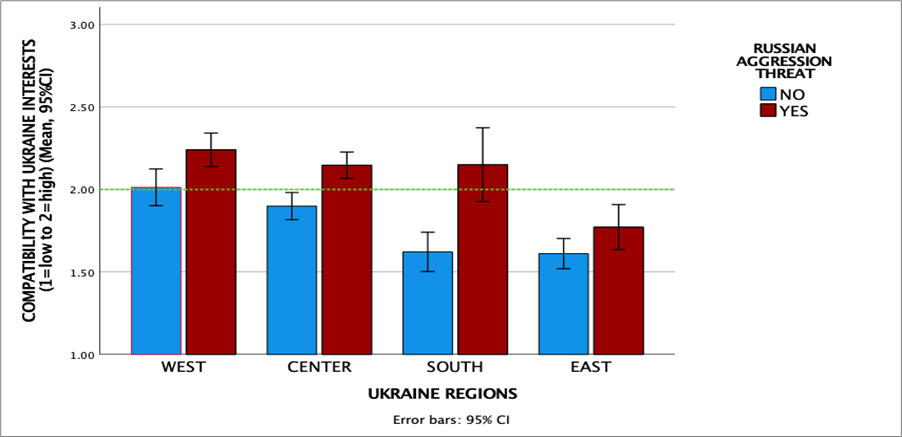

Nearly 70 percent of respondents believed the United States policies were partly or mostly compatible with Ukraine’s national interest. And when asked about U.S. influence on Ukraine’s domestic politics, only 25 percent of respondents felt such influence would harm Ukraine, while 33 percent said it would benefit Ukraine. Another 42 percent were ambivalent, saying U.S. influence is sometimes beneficial.

While aspirations for stronger relations with the United States run high, the plurality of respondents equivocated on the U.S. policies’ compatibility with Ukraine’s interests and the domestic benefits of those policies for Ukraine.[1] The prevalence of respondents viewing U.S. policies as incompatible with Ukraine’s national interests (30 percent) over those viewing them as compatible (22 percent) is cause for concern (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ukrainians’ View of Relations with the United States: Priority, Compatibility, and Benefits

Moreover, regression analysis shows that support for cooperation with the United States is strongly and about equally associated with both the perceived compatibility and benefits of U.S. policies. If 10 percent of Ukrainians who view U.S.-Ukrainian policy as compatible with most of Ukraine’s interests become ambivalent, then about 6 percent of Ukrainians who view cooperation with the United States as strategically vital would prefer to limit cooperation to specific issues on a case-by-case basis. The likelihood of this association occurring by chance is less than 0.1 percent.

Behind Likes and Dislikes: Society and Geopolitics

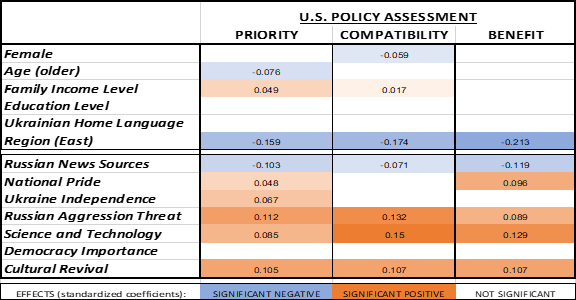

Geopolitical legacies and concerns about sovereignty come through as the strongest correlates of U.S. policy assessment in Ukraine. Support for relations with the United States progressively declines from western to eastern Ukraine, but it is consistently stronger across regions and social groups among respondents who want to see Ukraine as a technologically and culturally thriving sovereign state, safe from Russian military aggression. Regression tests reveal the role of each factor, all other factors being equal (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Correlates of U.S. Policy Support in Ukraine Based on Regression Analysis

Meanwhile, support for cooperation with the United States is unrelated to education level and to the appreciation of the importance of democracy. The latter, in particular, raises questions. One thing is clear: the answer is not due to the lack of democracy support in Ukraine, with about 70 percent of the UNASIS survey respondents considering democracy important or very important to them personally. Additional analysis also showed that big economic concerns among Ukrainians—unemployment and wage arrears—were not related to their views of U.S.-Ukrainian relations. However, Ukrainians fearing price hikes viewed relations with the United States as less compatible with Ukraine’s interests and less beneficial than other respondents.

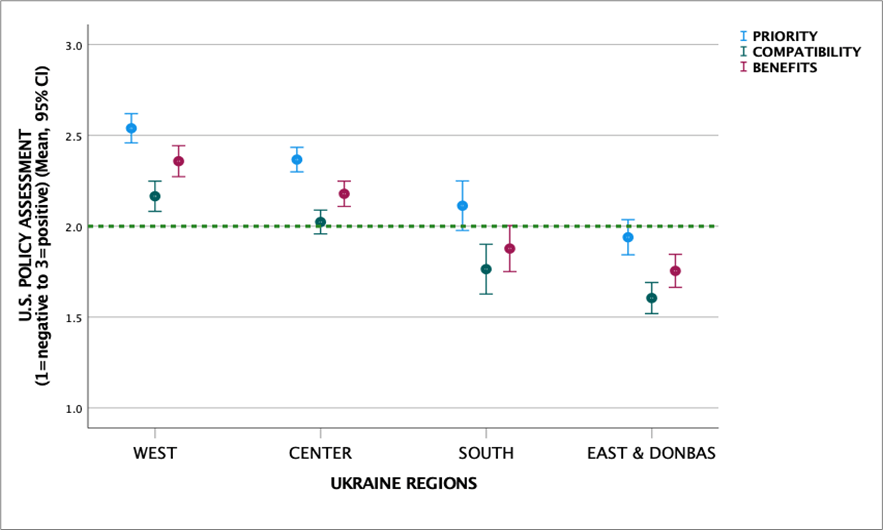

Turning to statistically significant predictors of U.S. policy support in Ukraine, a more detailed look at the distribution of responses across Ukraine’s regions offers important takeaways.

- Assessments of priority, compatibility, and benefits of cooperation with the United States are leaning positive in the West and Center and negative in the South and East (including the government-controlled Donbas areas). However, priority is viewed as high in the South and medium even in the East (see Figure 3), suggesting the goodwill reservoir is deep throughout Ukraine. On the other hand, only in the West are views on U.S. policy positive on all three dimensions. In the Center, Ukrainians are, on average, rather ambivalent about the compatibility of U.S. policy with Ukraine’s national interest. It appears Washington policymakers need to watch out lest its policies deepen Ukraine’s regional cleavages.

Figure 3. Views of Relations with the United States in Ukraine by Region (Nov.-Dec. 2020)

- Standing by Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity is pivotal. UNASIS respondents who saw “aggression by external enemy” (implying Russia) as the biggest threat to Ukraine (43 percent) were significantly more likely to see cooperation with the United States as strategically important, as highly compatible with Ukraine’s national interests, and highly beneficial for domestic political development. This is the case across Ukraine’s regions, bumping it up in the South to the level of the Center and the West (see Figure 3). Strikingly, in none of Ukraine’s regions is the average view of Washington’s Ukraine policy net positive among Ukrainians who do not see Russian aggression as the principal threat to their country.

Figure 4. U.S. Policy Compatibility with Ukraine’s Interests by Region & Russian Threat

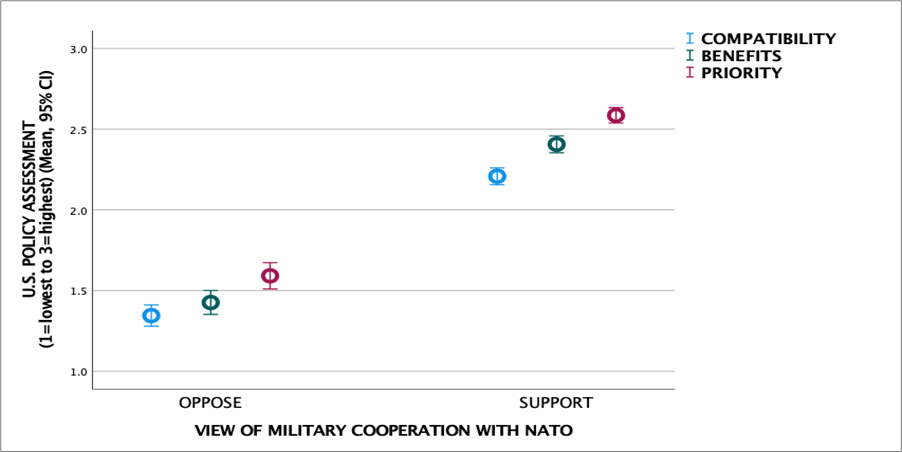

- Support of 67 percent of Ukrainians for military cooperation with NATO is another mainstay of public goodwill toward the United States. Respondents favoring such cooperation are on average twice as likely to view U.S. policy positively as those who oppose it (see Figure 4).

Figure 5. View of U.S. Policy Through the Prism of Military Cooperation with NATO

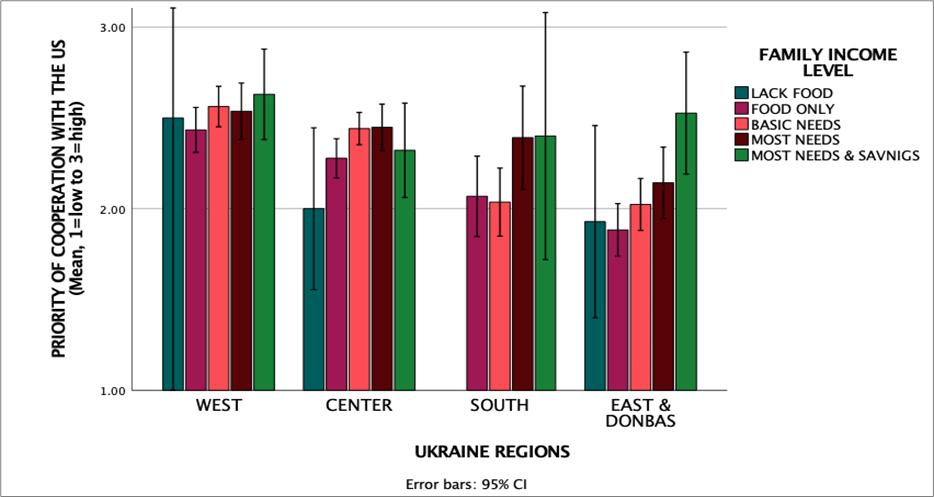

- Poverty alleviation deserves stronger attention. Among the bottom 35 percent of respondents by family income, views of U.S. policy toward Ukraine have been mostly ambivalent or negative. By contrast, Ukrainians reporting household incomes sufficient to cover their basic needs and higher have been predominantly positive on U.S. policy. And the top 6 percent of respondents by income strongly support U.S. policy at about the same level in all regions (see Figure 4). Notably, in Ukraine’s West, where Euro-Atlantic orientation has been historically strong, preferences for cooperation with the United States differ little by income. The farther east one moves, the more income is a factor. This means helping with economic development in the southern and eastern regions would be of particular benefit for U.S. support in Ukraine.

Figure 6. Priority of Cooperation with the United States by Region and Income

- Engaging with Ukraine’s science, technology, and culture is also worthwhile. Respondents who see those areas as important for Ukraine view cooperation with the United States mostly positively across regional divides. Respondents who find “national-cultural revival” and “achievements in science and technology” very important are predominantly positive on U.S. policy from West to East Ukraine and with no significant variation. Among other respondents, approval of U.S. policy declines significantly from West to East (in a pattern close to that in Figure 5).

- The surveys show that fighting corruption is neutral to U.S. policy assessment. Respondents who believe that corruption is the main threat to Ukraine are no more or less likely to view any aspect of relations with the United States differently than those who are not concerned about corruption.

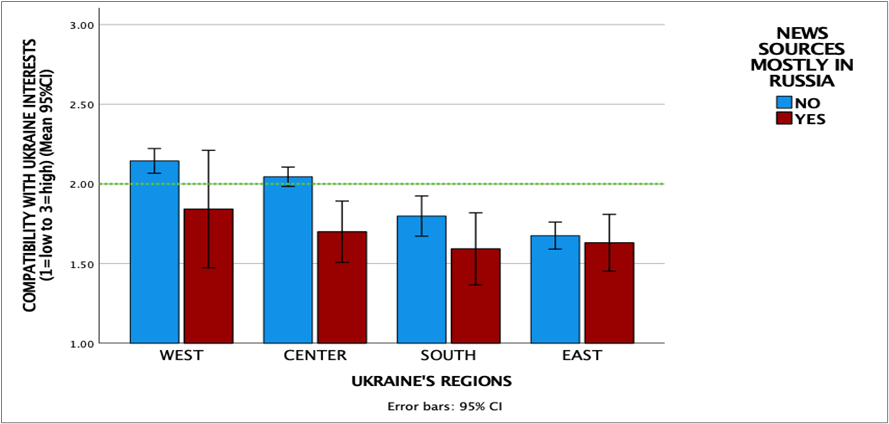

- Russia-based media do damage. Receiving most of one’s news from Russian sources (13 percent of respondents) reduces the average Ukrainian’s level of U.S. policy approval in the Center to that in the East (see Figure 7). Those users—regardless of what languages they speak at home–predominantly view cooperation with the United States negatively or ambivalently in every region of Ukraine (below “2” on a 1-3 scale).

Figure 7. U.S. Policy Compatibility with Ukraine’s Interests by Region & Russian News

Pivotal Linkages: Europe vs. Moscow

The UNASIS 2020 survey indicates that support for Ukraine’s integration with the EU would boost public support for the United States in Ukraine. First, Ukrainians view relations with the EU more positively than with the United States. In particular, about 52 percent of respondents call relations with the EU strategically vital, compared to about 45 percent for the United States. Second, Ukrainians who used visa-free travel to Europe (11 percent of respondents) are more likely to see relations with the United States as strategically important. The latter applies in every region of Ukraine and particularly so in the West, South, and East.

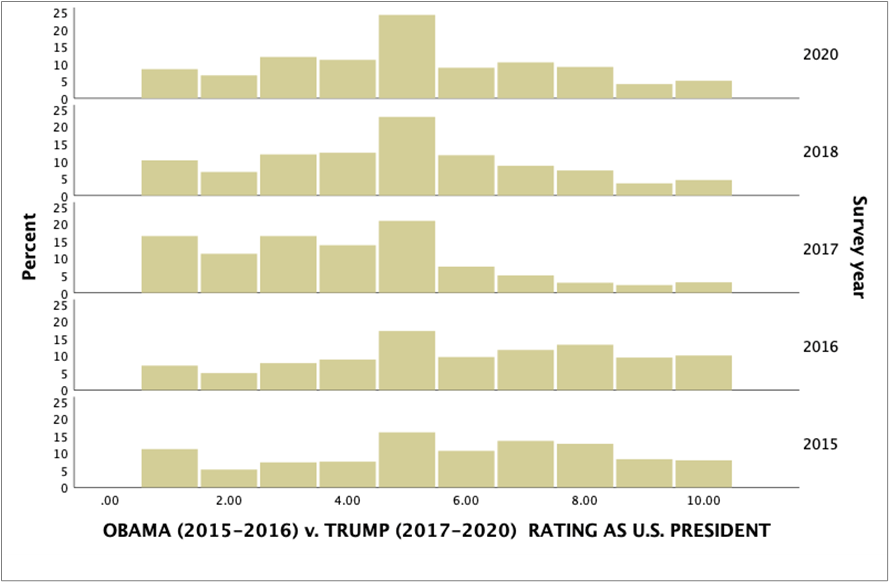

But it is Washington’s relations with Russia that are pivotal when it comes to Ukrainian public perceptions of U.S. policy toward Ukraine. The way Ukrainians rated the performance of U.S. presidents in UNASIS annual surveys from 2015 to 2020 offers strong evidence. A sharp drop in approval ratings from Obama’s last year (2016) to Trump’s first year (2017) is particularly telling (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Assessment of U.S. Presidents Performance in Ukraine

The context is well known. Trump’s praise of Russia’s authoritarian leader and high-profile mainstream media reports about Trump’s election-campaign interactions with Moscow, as well as Trump’s deriding of well-documented reports of Russia’s interference in the U.S. 2016 presidential election, made it appear plausible that upon becoming president, Trump could ease or remove sanctions on Russia imposed in response to Moscow’s annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula and its military intervention in the Donbas. In subsequent years, as the sanctions stayed in place and U.S. military assistance to Ukraine increased, Trump’s ratings improved.

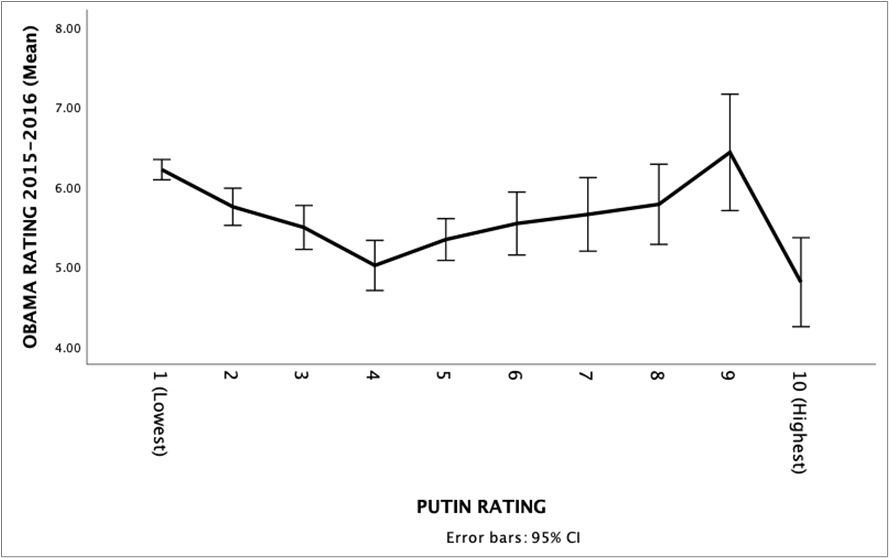

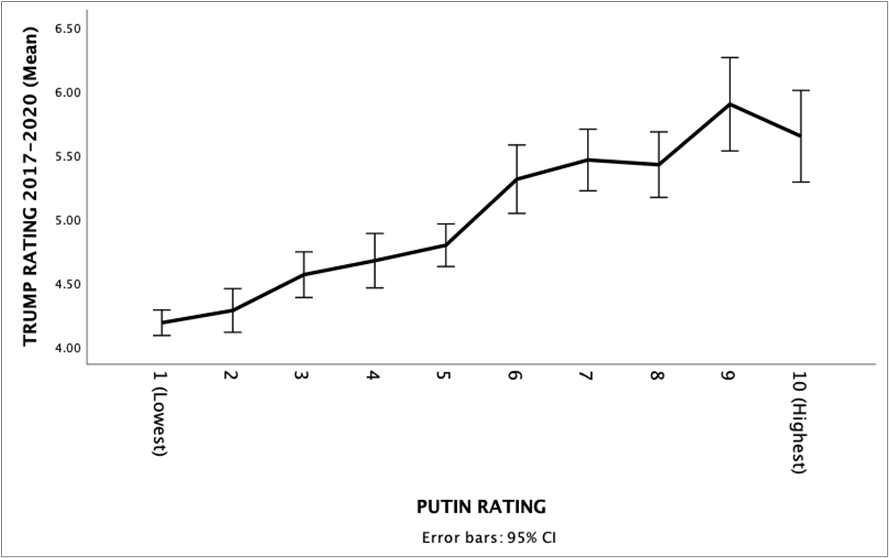

Meanwhile, Trump’s perceived sympathy for Putin likely kept his ratings lower than Obama’s in Ukraine. The UNASIS data show that approval of Obama in Ukraine in 2015 and 2016 correlated with disapproval of Putin. Conversely, approval of Trump in 2017, 2018, and 2020 strongly correlated with approval of Putin (see Figures 9).[3] Both relationships would be only 0.1 percent likely to occur by chance.

Figures 9. Relationship Performance Ratings of U.S. Presidents and Vladimir Putin

Obama-era Rating

Trump-era Rating

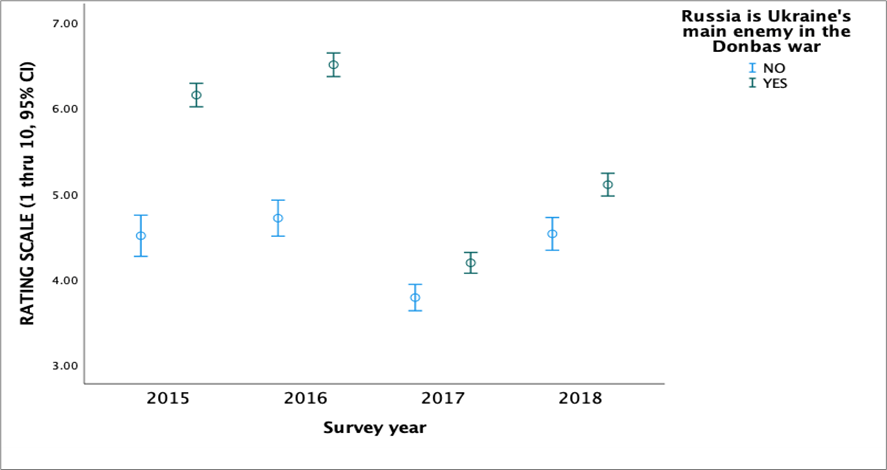

But regardless of who was in the White House, the Russian threat loomed large. Ukrainians who viewed Russia as Ukraine’s main enemy in the Donbas war rated the U.S. presidents significantly higher than did those who viewed other actors as the main enemy (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. U.S. Presidents’ Approval in Ukraine

Conclusion

Opinion data—the proverbial wisdom of the crowd—has important messages for Washington on how to orient and frame its foreign policy to gain the most positive resonance in Ukraine and to avoid the most negative resonance. The principal issue is Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, which, among the Ukrainian public, strongly relates to keeping as many constraints on Russia’s interference as possible. For Washington, this also means that any rapprochement with Moscow would come at a price of weakening Ukraine’s resolve to be America’s willing and reliable geopolitical ally. When weighing the benefits of any putative cooperation with Russia, the White House would be wise to ask whether its uncertain benefits—given Putin’s opacity, obfuscations, and deeply held anti-Americanism—are worth the risk of losing traction in Ukraine and potentially destabilizing it. Any Kremlin proposal, for example, to engage jointly with the Taliban regime in Afghanistan or with Iran on nuclear issues would be exactly an issue to be considered from this angle.

Surveys indicate that the best way for the United States to win friends and influence people in Ukraine is to help Ukraine develop as a territorially secure, militarily strong, and technologically advanced ally. Fitting this logic, among other things, would be not only tightening sanctions on Russia but also increasing military assistance to Ukraine and practical cooperation between Ukraine’s armed forces and NATO; stepping up cooperation in defense-related high-technology research, development, and production (particularly with respect to weapons capable of credibly deterring Russia from further military interventions). Regarding the latter, the United States can also benefit from engaging more actively with Ukraine’s advanced and internationally competitive space/missile, aviation, and information technology sectors. Achieving significant progress in collaboration on projects such as Motor Sich aircraft engines (following Ukraine’s cancellation of the company’s sale to China upon Washington’s request) and the development of coastal defense missile complexes would be an example of such an approach.

Supporting anti-corruption efforts and democracy is not going to have a negative impact on Ukraine. However, pitching those policies as a stand-alone priority would risk undermining support for the United States through implicitly downgrading support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and security. Perhaps policymakers in Washington could find a way to integrate and link those issues. If they do so, they would be wise to place the main accent on Ukraine’s sovereignty.

Mikhail Alexseev is Professor of Political Science at San Diego State University.

[1] In addition, those questions had a high rate (23-24 percent) of “don’t know” responses. Following the methodologically safest strategy, they were excluded from statistical analysis.

[2] In the UNASIS (October-November) 2019 survey the question was not asked.

[3] The correlation coefficient was -0.114 for Obama and Putin; and 0.219 for Trump and Putin.

Image credit