Image credit/license

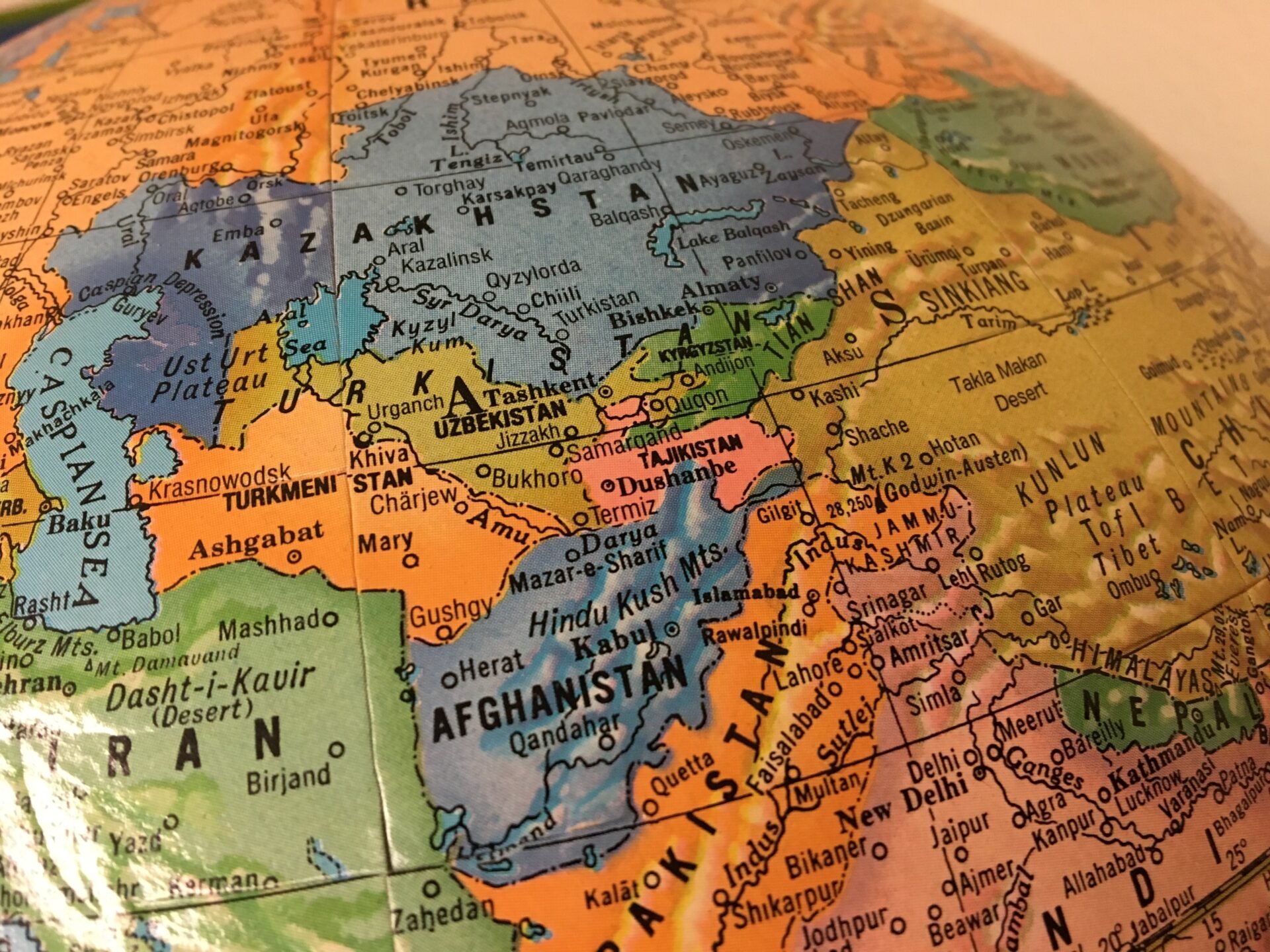

In late June 2024, the Department of Homeland Security announced it had identified over 400 mostly Central Asian migrants they tied to a people-smuggling network with suspected links to ISIS. Only weeks before, federal agents had arrested eight Tajik nationals in New York, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia, with reported ties to terrorism and who had crossed the U.S. southern border illegally. This is the most tangible indicator yet that concerns have re-ignited in the United States about the potential terrorist threat from Central Asia, which last became an issue on Halloween of 2017 when an Uzbekistani man from Tashkent murdered eight people on behalf of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) on the west side of Manhattan, in New York’s deadliest terror attack since 9/11.

These recent arrests follow a string of disrupted terror attacks linked to Central Asian migrants in alleged cells of the offshoot group, ISIS-Khorasan (ISIS-K), in Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands in just the past few years. These are a sober reminder that despite the urgency of the wars in Gaza and Ukraine, we cannot turn our backs on the desperate situation many migrants from Central Asia face by merely hoping that they will not spill over to our own lives.

Trapped in a Vicious Cycle the World Ignores

Years of research investment has broadly identified the underlying causes that make Central Asians vulnerable to extremist groups. But in the intervening years between the attacks in New York, Stockholm, and Istanbul of 2017 and the Crocus attack in Moscow in March of 2024, the United States, European Union, and other international partners have largely abandoned projects that address the root causes of violent extremism in Central Asia or support the region’s returnees from the Syrian conflict, forced in part to cave under pressure from local governments to declare a “job well done.” Persistent failure to meaningfully address the underlying factors that drive this mobilization threatens human security in Central Asia and has consequences for our own security as well.

These underlying drivers that lead to violent outcomes are only growing worse as Central Asian migrants pushed out of their homes in an effort to survive find themselves trapped and instrumentalized in three conflicts at once: (1) pressured by Russia to backfill its private and conscripted military ranks for its war of aggression in Ukraine, (2) recruited by ISIS for its global agenda and punished collectively for the actions of the very few who join, and (3) made into totems of securitization and the migrant “threat” in the United States and Europe when they try to escape.

While the United States is far removed geographically from the issues that face Central Asians in their everyday lives, they are surrounded by messages from their home governments, Russia, and extremist organizations that blame the United States and Western liberal democracy for the hardships they experience. This was a key narrative in ISIS messages to Central Asian migrants since it began recruiting them in 2013. ISIS-K originated as a mutiny within the Taliban, and the bulk of ISIS-K’s attacks in recent years have been part of the long Afghan civil war. But the Central Asian contingent within main ISIS recruited primarily among labor migrants in Russia like those who allegedly carried out the March Crocus Attack. These recruiting messages often echoed Russian propaganda that migrants are already steeped in, and which has long identified the United States as Russia’s most important enemy and the supposed origin of the grievances ordinary Tajik and Uzbek migrants face in their everyday lives at home and abroad.

Only a few years ago, thousands of Central Asians took their whole families to migrate to what they were promised would be a new state for Muslims in “frontier” territory carved out of Syria and Iraq that promised an alternative to the pseudo-democracies they lived in and the liberal democracies that they were told were out to destroy their cultures and societies. Some 2,000 of them, overwhelmingly women and children, have now returned from camps like al-Hol in northern Syria. The Central Asian states have by far returned more of their citizens from the Syrian conflict than any other region in the world. But while there have been some efforts to support them, as of today, the majority of these programs have ended and most returnees have been thrown back into the same situation they or their parents tried to leave because they were not sustainable either economically, socially, or politically. We cannot hope to prevent new cycles of violence without addressing this core problem.

Most Central Asians who cannot see a future for themselves at home migrate to Russia. Following the Crocus Attack in Moscow on March 22, 2024, Central Asians simply trying to feed their families, make ends meet, or flee imprisonment and torture for their religious and political beliefs at home have found themselves increasingly made into objects of security in Russia and when they return home. They are even more stigmatized for their ethnicity and religion in Russia than before the Crocus Attack. And to add to that dehumanization, they are mobilized by those who want to use their bodies as suicide bombers in Vienna or Tehran; cannon fodder in Ukraine; or trade goods for human traffickers, including those who smuggled them across the US southern border.

The Russian economy and increasingly its war effort depend on this mass migration. Moscow has no interest in providing safe alternatives or improving the situation at home so that fewer Central Asians feel the need to leave. Instead, Russia increasingly pressures Central Asian governments to finally crush struggling independent civil society groups that might support the most vulnerable, to cut their countries off from Western influence that might support alternatives to the authoritarian control that has led to rampant inequality and unresolvable political conflict, and to cease cooperation with U.S. and European governments on preventing terrorism even as they seek to expand support for their own efforts to punish domestic opposition or dissent by calling it counter-terrorism.

But even before that pressure on civil society and efforts at state capture of counter-terrorism efforts increased, since the flow of foreign fighters to Syria has ended, the U.S. and EU and multilateral organizations have cut their involvement in preventing violent extremism (PVE) in the region dramatically. Despite years of good research data on key hotspots for recruiting, as well as vulnerability factors that could help protect Central Asian migrants from ISIS-K recruiting, we are fast approaching a point at which we will be doing little more in Central Asia than offering token funding to superficial awareness-raising programs to prevent terrorism, support the reintegration of returnees from Syria, and protect migrant workers from being exploited by terrorists, the Russian Army, or human traffickers. But years of experience in public health support for migrants and their home communities suggests there is much we can do, despite the political challenges we face to protect Central Asians from being exploited and improve their situation at home—at least to a level at which migrating with their families to a war zone or strapping on a suicide vest is no longer the most attractive alternative.

Migration and Displacement as Survival Mechanisms

Central Asians in Russia are part of the world’s second-largest migration pipeline (the first being those from Latin America to the United States). In Russia, they work in construction, agriculture, the service industry, and bazaars, often under harsh conditions. They get paid little and are always at risk of getting cheated out of wages. They live in dormitories or other overcrowded housing. They are at risk of health problems and injuries and have no access to healthcare. They are often subject to arrest, detention, and bribery by the police. They get attacked by Russian nationalists. In Tajikistan, the country of origin for the overwhelming majority of suspects arrested in connection with recent ISIS-K operations, most families send at least one male to Russia to work and send back wages and depend on that income for their economic survival.

The Russian government increasingly offers citizenship to Central Asian migrants, but this makes them eligible to be drafted and many are. Others are offered work digging trenches or collecting the dead bodies of soldiers in Russian-occupied territories in Ukraine. Migrants all over the country are now being subjected to even more arbitrary document checks that in the past have often led to effective press-ganging into the Russian Army. Now that Russian police and security services have officially accused Tajik labor migrants of betraying their host country for Ukraine by accepting money to carry out the Crocus Attack, the pressure among ordinary migrants to prove loyalty by enlisting in the military will likely skyrocket. Fear of being forced to serve in Ukraine contributed to increasing numbers of Central Asian migrants in Russia making their way to Latin America, then crossing into the United States over its southern border just as those recently arrested did. Migration to Russia has long put a band-aid on myriad economic problems for migrants and their countries of origin, but increased securitization and pressure to accept conscription or work in occupied territory in Ukraine leaves thousands seeking other options.

Migration is a survival strategy; it is sometimes the only way many Central Asians can manage the lack of adequate support and livelihood opportunities in any one place. When one avenue closes, they will find another, and recent history tells us that some of the most desperate and disaffected may well look for protection from an armed group that promises—even if falsely—to fight on their behalf. Labor migration is not by itself a security problem, nor are labor migrants somehow inherently dangerous, but the economic and social niche that migrants occupy is fraught with the same vulnerabilities that extremist recruiters can exploit. And this is a problem that we cannot hope to solve with force or policing alone: we have to help migrants establish safety and address the root causes that push some into the arms of those who manipulate them by promising it.

Central Asia’s Complex Problems of Human Security Did Not Disappear When the Syrian Civil War Ended

Pushback against addressing these root causes that push migrants into conflicts and terrorism is the default position of Central Asian governments, who have their own incentives for allowing mass migration to temporarily relieve social pressures these root causes create. For Russia, labor migration and potentially increased conscription are key tools in winning the war to destroy an independent Ukraine. In Central Asia, the first priority is ensuring the stability of the authoritarian status quo, which was never meaningfully threatened by the outflow of citizens to die in Syria, Iraq, or Ukraine.

To the extent that terrorism prevention is being conducted in Central Asia and Russia, it is typically messaging campaigns focused on “fixing” people’s religious beliefs, which fails to address the underlying issues that have made thousands of Central Asians vulnerable to recruiting by armed Islamist groups. We have been working with a network of community and Islamic activists, mental health practitioners, and migrant support organizations across Central Asian countries who are focused on addressing a broader range of socio-ecological factors that characterize the life experiences of labor migrants and other citizens at risk of recruitment into violent extremism, gangs, and other maladaptations that undermine human security in the region.

Such approaches, based on best practices and a public health approach to violence prevention, look to diminish upstream risk factors, such as discrimination, and work, legal, or financial difficulties; and they seek to strengthen protection factors, such as family and community support. The communities where migrants live and work in Russia and beyond could be the focus of such prevention activities. Prevention could also be carried out by the governments of the countries where they are from, when they are back home, in the same way that those countries have built migrants’ knowledge and skills concerning HIV prevention, for example, through migrant resource centers in Tajikistan.

Alternative Pathways to Safety and Survival

Despite the collapse of international support for programs that address root causes of violent extremism, important work along these lines is already being done by local practitioners who know their own context and the needs of their communities better than anyone else. But currently these practitioners lack support from a broader network and the knowledge of international best practices that could help justify to their own governments their willingness to go against the official line that ideology, Islamic diversity, foreign ideas or individual greed are the sole causes of terrorism.

In Uzbekistan, for example, independent activists, including several freed in the 2017 amnesties that released long-held political prisoners after the death of former President Islam Karimov, struggle despite reforms to help other former convicts found guilty on extremism charges overcome stigma, to reconstruct their social networks of support and care, and find local employment.

In Kazakhstan, a counselor we partner with supporting returnees from Syria created a private group in which her clients can contact her day and night when they face challenges, experience family conflicts, or just need someone to talk to when memories of their trauma keep them up at night. She continues to operate the project long after her funding has run out.

In Tajikistan, trauma training for physicians in local health clinics continues to have an impact especially for women facing domestic abuse—an endemic public health crisis in the region that has finally become a topic of widespread public debate following the conviction of a former high-ranking minister in Kazakhstan who beat his wife to death in a restaurant. Despite their diversity, these public health problems are not unrelated: the physical and sexual abuse of women and girls has emerged as a significant factor in the lives of women who were later mobilized to join the Islamic State in Syria.

Conclusion

Activists, practitioners, and physicians in Central Asia should not have to struggle to solve these problems alone. They need and deserve support to create networks to share experiences, challenges, and best practices, and to build relationships with their peers in the rest of the world who are facing many of these same challenges. Burnout rates are especially high among those working in peripheral hotspot communities that are most marginalized and at risk, and many are pushed to migrate themselves in order to ensure the survival and well-being of their own families. But now is not the time to turn away in the hope that, since the flow of foreign fighters to Syria has ended, we can ignore the suffering of those living on the edges of Russia’s imperial ambitions or the territory ISIS-K hopes to one day control.

While overshadowed by the crises in Afghanistan, Syria, Gaza, and Ukraine, alongside immigration debates in the United States, Central Asian migrants are caught in the middle of each of these crises and are pulled into each of them. The political incentives in Russia and in Central Asia are high to declare a “job well done” on solving violent extremism and focus on other issues. But the evidence shows that this is a problem with deep roots, not solely one of ideology or narratives that can be solved with counter-messages. The problems that are pushing Central Asians out of their home communities and into danger are not just words or misinformation. Ramping up the rhetoric of “dangerous migrants” does nothing to improve the situation, and only adds to the difficulties migrant’s face. Helping Central Asians find safe means of migration or alternatives to migration, and protecting them from political and religious persecution in their homelands and adopted homes, is linked to preventing the escalation of each of these crises: improving the human security of the people of Central Asia helps improve ours, too.

Stevan Weine, MD, is professor of psychiatry and Director of the Center for Global Health at the University of Illinois College of Medicine. [1]

Noah Tucker is an associate at the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Affairs at Harvard University, and holds a Handa Studentship at the Handa Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence at the University of St. Andrews; he is also a program associate for the Central Asia Program at the Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies at The George Washington University

Image credit/license