(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Benjamin Franklin once remarked, “Those who would give up essential liberty, to purchase a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety.” His words capture one of the most fundamental trade-offs in politics: individual liberty vs. public security. Although Franklin clearly believed in the overwhelming importance of the former, its value relative to the latter becomes more difficult to ascertain when public emergencies generate extreme danger or uncertainty. Faced with dangerous circumstances such as wars, terror attacks, or pandemics, people are often asked to give up certain freedoms. The question for policymakers is whether and how to convince citizens to accept potentially intrusive measures for the sake of public security during an emergency. When presented with a proposal for new emergency measures, how much do the justifications, safeguards, and restrictions matter to the public?

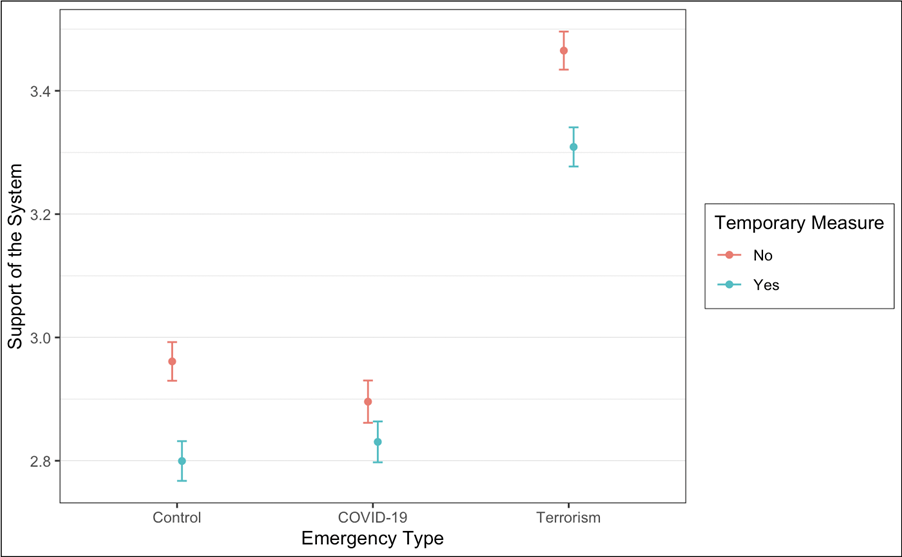

Our research suggests that Russians’ willingness to support a particular emergency measure—an automatic location tracking system—is nuanced and depends on how the measures are framed. The Russian public is generally much more willing to support implementing such systems when framed as an anti-terrorism tool than under normal circumstances. Russians are no more supportive of such systems when implemented to address COVID-19 than they are in normal times, however. As a rule, systems explicitly framed as temporary (regardless of the type of emergency it addresses) are viewed less favorably. What drives this pattern, and is it context dependent?

Balancing Liberty and Security

Cross-national evidence on the public’s willingness to trade off privacy, a crucial liberty in most societies, for safety, in order to address emergency situations, suggests a great deal of variation. Marcella Alsan and co-authors used a representative survey of 480,000 respondents in 15 countries in 2021 to show that during the COVID-19 pandemic, while only 5 percent of Chinese respondents replied that they would not give up any rights during times of crisis, in the United States, it was 20 percent. Similarly, Gallup International conducted a survey of 25,000 respondents in 28 countries and found substantial cross-national variation in the percentage of people who are willing to give up some of their rights if it helps prevent the spread of the coronavirus. It is as high as 95 percent in Austria, 60 percent in Russia, and as low as 32 percent in Japan.

The scholarly consensus attests that in times of crisis, people tend to be more willing to trade away their fundamental civic and political rights for the sake of safety. However, people do not automatically support just any emergency measure. Proper governmental framing of a crisis and its solution is an important factor that shapes public support for measures that violate rights and privacy. Alsan’s experiment in 15 countries suggests that citizens tend to favor measures credibly pitched by officials as both necessary and temporary. That is, they must frame the measures as important to combat a serious, present threat while also reassuring them that their rights will be returned once the crisis abates. This work is consistent with previous work by Darren Davis and Brian Silver on attitudes toward anti-terror measures, which shows that trust in government and institutions, privacy concerns, and personal senses of insecurity are all important drivers of support for measures that infringe on civil liberties.

However, much of the existing evidence on the liberty-security trade-off comes from established, relatively wealthy Western democracies. Russia is characterized by a very different historical experience and institutional context. On the one hand, exposure to communist rule profoundly shapes Russian public opinion, creating greater support for communitarian (as opposed to individualistic) policies. Such a tradition may form the extent to which individuals find emergency powers to be a violation of rights to begin with, as well as support for such measures even if they are seen as violations.

People in other settings might not value civil rights and privacy as much as citizens in wealthy democracies do. According to Lewis Siegelbaum, this is particularly likely in post-socialist countries where people did not experience privacy or freedom for decades under communist rule and historically lacked experience with democracy. In the World Value Survey in 2020, respondents in post-socialist and communist countries preferred security over freedom by a large margin: 7 percent in China, 24 percent in Russia, 27 percent in Kazakhstan, 30 percent in Ukraine, and 33 percent in Romania think freedom is more important than security. This compares with 43 percent in South Korea, 43 percent in Germany, 51 percent in Australia, and 70 percent in the United States.

For its part, Russia has been characterized by relatively limited political competition and widespread public corruption. Under such circumstances, the public may be more skeptical of government attempts to take emergency powers or claims about their purpose and limits. Such fears are likely justified since authoritarian settings lack institutions to serve as safeguards against encroachments upon civil liberties.

A Willingness to Give Up Freedoms to Fight Terrorism, but Not COVID

Emergency situations, such as wars, global terrorism, natural disasters, and pandemics threaten human lives and often call for extraordinary government responses. Most anti-terrorism measures around the world include intrusive surveillance and, at least to a certain degree, encroach upon human rights, especially liberty and privacy. For example, in Russia, telecommunications operators can provide subscribers’ locations under special circumstances, including for counter-terrorism operations. Since 2016, telecommunications and Internet companies in Russia have been required to store all user content for six months, retain data for three years, and provide access to the data to the FSB upon request.

The current COVID-19 pandemic, which so far has claimed the lives of more than 5 million people globally, has reinvigorated debates about constraints vs. liberties. For example, in Russia, the Ministry of Telecom and Mass Communications has been tracking the contacts of patients with COVID-19 by geolocation since spring 2020. Curiously, people in Russia seem to support certain measures, even though they agree that such measures violate their rights, but not other measures. Our study sought to explore people’s willingness to trade off rights for safety in the Russian context with a focus on two dimensions. On the one hand, the acceptability of emergency measures may differ across the types of crises that they address. The public may be less accepting of measures taken during normal times than those taken to address concrete crises such as COVID-19 or terrorism. On the other hand, the public may also be more accepting of measures that are explicitly framed as being temporary in nature.

To study these questions, we conducted a survey of more than 16,250 respondents in 60 regions of Russia between August and September 2021. To measure attitudes toward a hypothetical location tracking system, we took advantage of an experimental vignette design in which individuals are randomly assigned to receive different types of information about the system. By varying the information respondents received randomly and comparing group aggregates, our experiment allows us to separate out the effects of the framing of the measure itself from other individual-level factors—culture, education, attitudes towards civil liberties, locality—that may influence support for emergency measures.

We showed our respondents the following prompt: “Imagine the government is proposing a new digital system that automatically locates all Russians.” Our experiment varied two possible dimensions: the circumstances under which the government system was proposed and its expected duration. The circumstances were: “to contain a dangerous infectious disease like the Coronavirus” or “to prevent forthcoming terrorist attacks.” The duration was “to temporarily introduce” such a system. Our control group was not provided with any justification or duration and served as a baseline to contrast with our treatment conditions. After seeing the proposal, respondents were asked whether such a system violates citizens’ rights and whether such a system is necessary even if some people view it as a violation of rights.

Results

As can be seen in Figure 1, Russian support for government measures, in this case, location tracking, is generally low regardless of how it is justified or the duration specified. This being said, there are clear differences across our experimental groups. When they were told the measure was meant to stop terrorist attacks, the group was much more supportive than when the measure was meant to prevent a pandemic or provided no justification. The figure also shows that although there are small differences between the groups that were told the measure would be used to fight a pandemic and the group provided with no information, although the differences are small enough to be attributable to chance measurement errors.

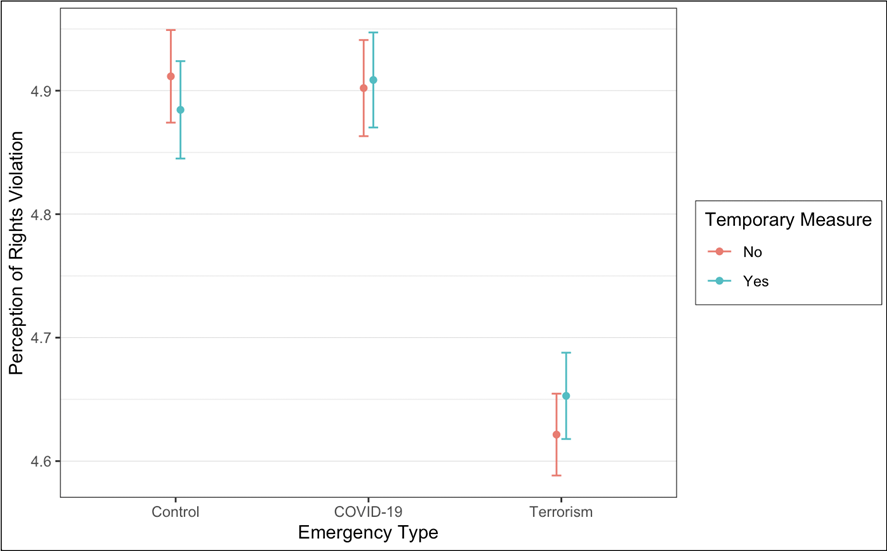

Figure 1: Agreement that the Emergency System/Location Tracking is Necessary

Intriguingly, when told the measure is temporary, support for it fell regardless of the emergency (or lack thereof) it was meant to address. Here differences were small but generally unlikely to be due to chance, with the exception of when pandemics like COVID-19 were the justification. Taken together, these results suggest that Russians are generally more accepting of location tracking as an emergency measure when it is framed as a tool to fight terrorism than in other circumstances. One potential explanation is that this has to do with how the measure is perceived vis-a-vis human rights. In particular, such measures may be viewed as less problematic for rights when framed within the context of terrorism than as part of pandemic responses or a general measure.

To assess this, we also asked respondents whether they agreed “Such a system would violate human rights” using the same seven-point scale as before. As is evident from Figure 2, Russians generally believed such measures were a modest violation of rights. Although differences are extremely modest between conditions, location tracking used to combat terrorism is viewed as marginally less of a violation than when such a system is used to fight a COVID-19-like pandemic or during normal times. There are no differences based on the duration proposed, however.

Figure 2: Agreement that the Emergency System/Location Tracking Would Violate Our Rights

Collectively, our results paint a nuanced picture of the Russian public’s support for location tracking as an emergency measure. The Russian public is generally much more willing to support such measures when they are taken to address terrorism than in other circumstances, despite the fact that such systems are only slightly less likely to be viewed as violations of rights when framed as anti-terrorism tools. Russians also seem to discount explicit claims that such systems will be temporary, treating proposals the same (both in terms of support and perceptions of rights violations) whether specific time horizons are mentioned or not.

When Do “We” Get Our Right Back?

Existing evidence attests that people generally agree to give up certain rights and freedoms in times of crisis. Trust in government and institutions, personal fear of threat, the relative valuation of freedoms, privacy concerns, and credible pitches by officials shape support for emergency measures across the globe. Our experimental evidence in Russia suggests that the type of emergency plays an important role in explaining people’s willingness to tolerate limits on their liberties. Our findings suggest that even if institutional trust plays into Russians’ calculus towards emergency measures, the government is given more leeway under some circumstances than others. At the same time, our survey also suggests the importance of perceptions of fear: Russians are generally more afraid of terrorist attacks than of catching the coronavirus. This stylized fact suggests that, as in many settings, perceptions of the gravity of emergencies weigh heavily on the Russian public’s support for emergency measures.

However, our findings raise another fundamental question: once people give up their privacy and freedoms, are they ever getting them back? Although restricting certain rights could be desirable and even necessary to cope with emergencies, political leaders could use them as a pretext to abuse power. The current pandemic has exposed this problem. Even in democracies, political leaders have taken up measures that threaten basic democratic principles: rule by decree, ban on demonstrations, revoking mayoral powers (Hungary), closing courts, using intrusive surveillance to track citizens (Israel), sending the military to control public spaces (Chile), and postponing elections (Bolivia). Tamás Krausz even compared the Hungarian measures to Ermächtigungsgesetz (Germany’s 1933 Enabling Act) and dubbed them “rehearsal of dictatorship.”

While it is hard to separate the extraordinary nature of the measures from the extraordinary times in which they are generally adopted, the true problem lies in whether powers persist past the emergencies they address. If politicians choose not to relinquish their newly acquired powers, this potentially diminishes the overall levels of liberty and democracy around the world. Such cases are distressingly common. For example, in the recent past, both the U.S. and Russian governments continued to use powers taken up to address terrorist threats long after the initial attacks that prompted them. Recent findings that public opinion is malleable and people’s support for intrusive measures depends on how they are framed and presented by governments only reinforces the plausibility of such practices. Distressingly, resisting the prolongation of such measures is likely to be particularly likely absent public support in settings where institutional bulwarks against human rights and freedom violations are weak. A silver lining, however, is that our findings suggest that the majority of Russians do value their rights and freedoms and are not ready to surrender them without extenuating circumstances. Thus, despite governments’ ability to strategically frame their policies, the public does not necessarily blithely accept any and all justifications.

Conclusion

Not all crises are created equal. Politicians’ ability to impose restrictions the public will accept is heavily curtailed by the types of emergencies that they are designed to address. We expect that similar variation might also be evident across measures that infringe upon rights other than privacy, with individuals more willing to accept more intrusive or politically centralizing measures under some circumstances than others. More comparative research in this field would be timely and important in the ongoing examination of the condition of liberty in Russia and worldwide.

Kirill Chmel is Junior Research Fellow at the Ronald F. Inglehart Laboratory for Comparative Social Research, and Lecturer in the Faculty of Communications, Media, and Design, School of Integrated Communications, Higher School of Economics (HSE), Moscow, Russia.

Israel Marques II is Assistant Professor at the School of Politics and Governance, and Research Fellow at the International Center for the Study of Institutions and Development, HSE, Moscow, Russia.

Michael G. Mironyuk is Associate Professor in the School of Politics and Governance, Programme Academic Supervisor, and First Deputy Dean, Faculty of Social Sciences, HSE, Moscow, Russia.

Dina Rosenberg is Assistant Professor in the School of Politics and Governance, HSE, Moscow, Russia.

Aleksei Turobov is Lecturer in the School of Politics and Governance, and Research Fellow in the Faculty of Social Science, HSE, Moscow, Russia.

PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 730

Image credit