(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Turkey and Russia have had a Janus-faced relationship in the post-Cold war era. While economic relations propelled by increasing energy ties have created a cooperative setting bringing the two states closer, differences in strategic positioning in the turbulent wider region exacerbate tensions, drawing them apart. On the one hand, Turkey has high levels of energy dependence on Russia and relies increasingly on Russian tourism revenues to mitigate its chronic balance of accounts deficit. On the other hand, the two countries have diametrically opposed geopolitical aims and have supported different sides in Syria and Libya. As reflected in the cases of the Russian annexation of Crimea, recent tensions in eastern Ukraine, and the second Nagorno-Karabagh war, Ankara and Moscow have diverging strategic interests across Eurasia. In the context of military alliances, Turkey’s decision to purchase S-400 missiles—a move that spilled their bilateral economic cooperation into the security realm—caused significant tension between Turkey and its NATO allies, particularly the United States.

In this complex setting, Turkey has been trying to strike an uneasy balance in its relations with Russia. It has pursued a strategy of compartmentalization to preserve their flourishing economic ties around their geopolitical volatilities. However, it is becoming more difficult for Turkey to maintain a compartmentalization strategy while sustaining many precarious transatlantic and Eurasian checks and balances. Any proliferating regional conflict means escalating tensions between, essentially, the United States and Russia, making Ankara’s equilibrium games exceedingly arduous.

Expanding Economic Ties and Energy Cooperation

The end of the Cold War created new opportunities for Turkey to mend ties with daunting Russia. The Expansion of economic ties has been the key driver for the Turkish-Russian rapprochement; these have been built around three main pillars: 1) investments, 2) tourism, and 3) trade. Russia has become the most important market for Turkish construction services and Turkish contractors (with a total value of projects surpassing $26 billion). Turkish direct investments in Russia have increased, reaching approximately $5.6 billion. Tourism is also a key sector where bilateral relations have grown at a rapid pace. While fewer than 500,000 Russian tourists visited Turkey in 1999, almost 5 million visited in 2017.

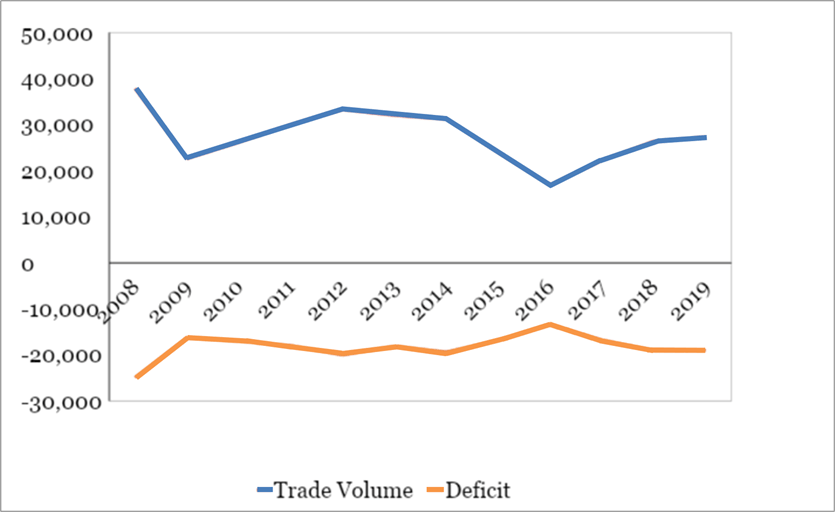

Overall, there is an asymmetrical trade balance between the two states, where Russia emerges as the key beneficiary due to energy exports. Figure 1 indicates this asymmetrical trade balance, with the deficit shown for Turkey.

Figure 1. Trade Relations between Turkey and Russia

The presence of rich energy resources has triggered significant geopolitical competition in the Caspian basin, with tantalizing prospects for global and regional actors. Although there is supply route competition between Russia and Turkey concerning the transport of land-locked Caspian energy resources to European consumers, high levels of energy interdependence between Ankara and Moscow also give way to economic convergence.

First, Turkey is a competitor for Russia as an alternative transit route. EU countries have high levels of dependence on Russian natural gas: Russian sources constituted approximately 46 percent of the EU’s imports of natural gas in 2019 and 43 percent in 2020. Caspian resources offer an appealing alternative for diversification and enhancement of European energy security, sparking competition between Ankara and Moscow regarding energy transport. Thus, Moscow views Europe’s initiatives for diversification since the 2000s within the framework of the Southern Gas Corridor—as well as increasing Turkish-Azeri energy cooperation with new projects such as the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline Project (TANAP)—as potential challenges to its dominant role in Eurasian energy politics, and Moscow strives to undermine them.

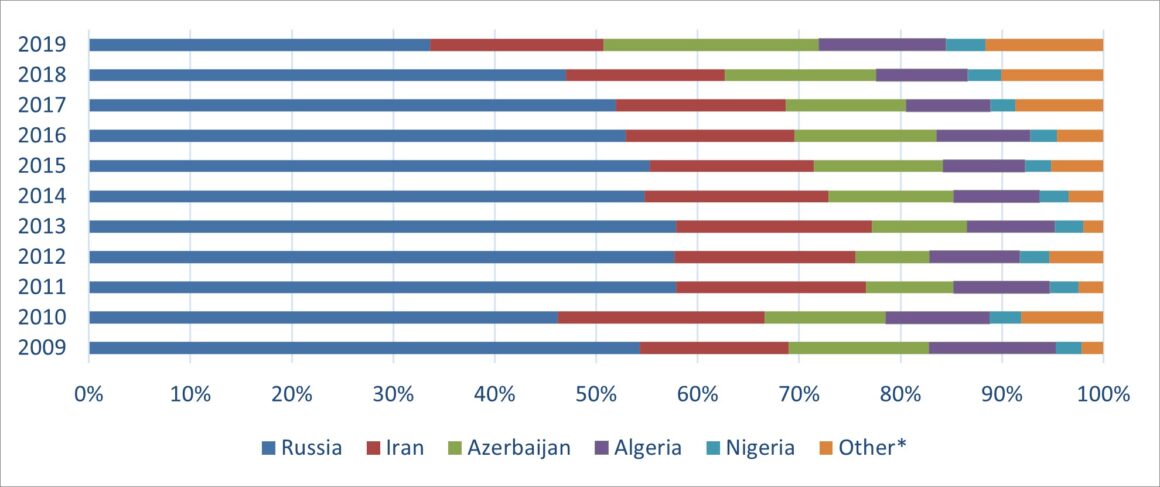

Second, Turkey has to prudently manage its own energy dependence on Russia. For instance, in 2019, 34 percent of Turkish gas imports came from Russia, making it the leading natural gas supplier for Turkey. Figure 2 indicates the percent share of imported natural gas to Turkey by source country in 2019.

Figure 2. Turkey’s Natural Gas Imports (%)

Given its energy dependence, in addition to its engagement in the east-west energy corridor, in December 2011, Turkey also signed an agreement with Russia to transport natural gas to Europe via the South Stream route that crosses the Turkish Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the Black Sea. It is striking that this agreement was reached just two days after the announcement of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for the TANAP with Azerbaijan. Since Russia had transit disputes with Ukraine, this agreement presented Moscow with a new opportunity to diversify its transit routes. In reflecting Moscow’s delight, Russian President Vladimir Putin even praised this agreement as a “New Year’s gift” from Turkey. This example shows that Turkey chooses not to jeopardize its ties with Russia due to their high levels of energy dependence while concomitantly developing Western-supported diversification routes.

Ultimately, problems associated with financial feasibility, the war with Ukraine, and divergences with the EU over regulatory frameworks regarding decoupling of energy generation from energy transport, all undermined Russia’s plans in South Stream. The Bulgarian government’s decision to suspend its participation in South Stream, giving in to EU pressures, was the last straw. The nascent project ended abruptly during Putin’s state visit to Ankara in December 2014 when he officially declared the cancellation of South Stream. In a surprise move, he also announced the Russian desire to replace South Stream with a new joint project with Turkey—later called Turkish Stream or TurkStream. This new initiative envisioned the construction of four parallel pipelines directly connecting Russia to Turkey under the Black Sea. The total amount of annual transport capacity is planned at 63 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas, with Turkey receiving 16 bcm for domestic consumption. While South Stream would have been a competitor to transit routes crossing Turkey as part of the EU-backed Southern Gas Corridor project, the Turkish Stream project led to the expansion of bilateral energy cooperation. There are, however, still some challenges for the project beyond Turkey’s borders, particularly regarding compliance requirements with EU energy regulations.

As a newcomer to nuclear power generation, Turkey also signed an intergovernmental agreement with Russia in the nuclear energy field. In July 2010, the Turkish Parliament approved the construction of Turkey’s first nuclear power plant in Akkuyu, Mersin. According to the agreement, the Russian state-owned atomic power company ROSATOM is handling the construction and operation of the Akkuyu nuclear power plant. For their part, Turkish leaders promote a nuclear power strategy stressing its advantages regarding energy supply security, financial benefits in terms of cost reduction, lower carbon emissions, and technological transfer possibilities. While Russia presented a commercially appealing deal, there are concerns regarding environmental impact and sustainability, including high-level waste and storage problems, potential adverse effects on marine life, challenges regarding the safekeeping of highly strategic materials, and risks of radiation leakages and accidents.

The establishment of a strong safety culture and the implementation of effective oversight mechanisms at every stage of nuclear energy production (from construction to decommissioning) are critical, and agreements with Russia should be carefully analyzed. Still, their nuclear energy pact has had a dual impact on their bilateral ties. First, the new Russian investment of approximately $20 billion into Turkey certainly deepens economic links. Second, while the project is presented as a diversification strategy, Turkey will become even more dependent on Russia in the energy field.

Deepening Geopolitical Fault Lines, Yet Strategic Partnership?

Russia and Turkey have different strategic interests and priorities on key regional conflicts such as Syria, Libya, Crimea, eastern Ukraine, and Nagorno-Karabagh. While Turkey and Russia were able to simultaneously sustain cooperation and operate in a competitive setting, their geostrategic divergences reached a climax over the Syrian conflict on November 24, 2015, when Turkey downed a Russian jet claiming that it had violated Turkish airspace. This incident is noteworthy since it is the first downing of a Russian jet by a NATO member in over half a century. Putin responded by declaring, “Russia is stabbed in the back by the accomplices of terrorists.” In turning this harsh rhetoric into action, Russia imposed sanctions on Turkey targeting tourism and agricultural exports to Russia. Moscow initially suspended the Turkish Stream project but basically spared all of their extant energy ties since they provide significant revenue for Russia’s rather troubled economy, which struggles with relatively low energy prices and the impact of EU sanctions due to the Ukraine crisis. Generally, energy ties were protected by long-term contracts.

After the jet incident, the restoration of bilateral relations took about seven months. After Ankara and Moscow started to mend their relations during the summer of 2016, an intergovernmental agreement on Turkish Stream was signed in October, and construction began in May 2017. While trade—and especially tourism—took a blow with the political crisis caused by the downing of the jet, once bilateral relations started to improve during the second half of 2016, there was a quick recovery in both areas. The incident, however, clearly revealed how geopolitical tensions could undermine bilateral economic ties.

Once the crisis with Moscow calmed, Turkey reached a decision to purchase S-400 missile systems from Russia, a strategic move that highly frustrated its NATO allies. The move to extend bilateral collaboration to the strategic arena served Putin’s desire to drive a wedge between Turkey and its Western partners. This sale particularly strained Turkish-U.S. relations, and sanctions were implemented against Turkey under the Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) in December 2020. Turkey was also removed from the F-35 fighter jet program. When Turkish-Russian collaboration enters the strategic-military realm, it can seriously undermine Turkey’s transatlantic ties.

On the flip side, Turkey’s drone sale agreements with Azerbaijan, Ukraine, and Poland have highly frustrated Russia. To the dismay of Moscow, drones produced by Turkey, with affordable digital technology, have effectively destroyed tanks, armored vehicles, and air-defense systems of Russian-backed fighters in Syria and Libya, and more recently in Azerbaijan and Ukraine. Azerbaijan procured TB2 drones from Turkey last year. These drones, as well as ones made by Israel, facilitated Azerbaijan’s victory over Armenian forces during the second Nagorno-Karabakh war earlier this year. Given the recent high Russian-Ukrainian tensions, Turkish drone sales to Kyiv also created unease in Moscow.

Conclusion

While there has been a recent rapprochement between Turkey and Russia, they have diverging perspectives about numerous nearby conflicts. Despite extensive economic cooperation, bilateral relations are quite far from strategic. The Syrian conflict—and particularly opposition-held, anti-Russian Idlib—remains as a potential powder-keg in their relationship. While the Russian engagement in the Syrian conflict has turned Moscow into a decisive actor in Turkey’s near abroad in the Middle East, Turkey’s military collaboration with Azerbaijan has enabled Ankara to extend its strategic influence in the South Caucasus.

Nevertheless, economic ties in the energy field foster cooperation despite strategic divergences. Turkey’s over-dependence on Russian natural gas compels Ankara to compartmentalize its economic and geopolitical interests. This strategy has mostly enabled both states to avoid potential spillover effects from geopolitical confrontations. However, as revealed during a major crisis, such as the downing of the jet, if fault lines deepen too much, all ties are threatened.

Turkey and Russia have a relationship—in defiance of many international relations theories—that presents significant opportunities for collaboration within substantial constraints. Due to their extensive economic ties, these unlikely partners are compelled to resolve differences through negotiation, yet centrifugal forces continually challenge a steady partnership. For their share, the West, United States, and NATO should refrain from alienating Turkey, which can serve Russian interests. As Selim Yenel, president of the Global Relations Forum, stressed, “The Biden administration should acknowledge this continued need for allies and treat them with due consideration if the United States is to build a resilient base that will not shift in the future.”

Şuhnaz Yılmaz is Associate Dean of the College of Administrative Sciences and Economics (CASE) and Professor of International Relations at Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey.