Among all European countries, Germany has the deepest tradition of not only engaging Eastern Europe politically and economically, but also discursively shaping Osteuropa as a region. Russia is a part of this East European imagery, though under different guises.

Recently, three different events took place in Berlin that unveiled three faces of today’s Russia and presenting three different messages to Germany’s policymakers.

Story 1: Ryzhkov’s Recipe

The German Society for Eastern Europe celebrated its 100 anniversary with a large conference that focused on a key question: apart from geography, what makes the EU’s neighbors European? The patriarchs of European politics—former German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher and former Polish Foreign Minister Wladyslaw Bartoszewski—share a rather inclusive view of Europe, one that embraces Turkey, Israel, Armenia, and Georgia. But what about Russia?

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a co-founder of the Russian oppositional party PARNAS, offered his take on this question: Russia’s way to Europe is hampered by Putin’s regime, which rebuffs European values. Former Soviet institutions—secret police obsessed with repressions, ubiquitous nomenklatura, the propaganda apparatus—have been regenerated from the past. What has to be added to this picture is the Orthodox Church taking the role over from the Communist Party’s ideological committee. Ryzhkov remarked: “Putin said that one shouldn’t treat the separation of state from the church too literally. Yet how can one be flexible with the legal norm?”

Ryzhkov deems that the major challenges for the Putin regime are ongoing legitimacy crises and new trends in energy markets that can potentially reduce Gazprom’s profits. Security troubles in the Caucasus and corruption make the system even more fragile. Russia already has the worst economic indicators among G20 countries. The Eurasian Union project, in his view, is basically about bureaucracy, security services, and state corporations: “they are concerned not about improving institutions, but only about investing money.

Ryzhkov went on to say: “Putin made his choice. His regime adopts inhuman laws, relies on the past, and lacks an idea for the future. He restored the corporate state in its purest: all ‘systemic parties’ stick together. On TV screens, all watch Putin and Medvedev, and then stories of the ‘degrading West.’ So far archaic and state-dependent segments of the society trump pro-European, reformist social groups that are fragmented and lack a common agenda, except for abstract slogans like ‘For Freedom.’ Competing with the ruling United Russia party, which receives 1.5 billion rubles per year from the budget is a hard job.”

For the German audience, Ryzhkov also had a message: “Look at dynamics in Ukraine, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Armenia—in almost the entire former Soviet Union, authoritarian regimes are restored, which is partly a result of Europe’s inaction. Such a contrast with the Baltic states! It is understandable that German corporate businesses don't want to lose markets. But will you keep silent should something more terrible happen in Russia? Do you feel any responsibility for the post-Soviet space?”

Ryzhkov's recipe for dealing with Russia is three-fold. First, the EU has to make the Kremlin fulfil its legal obligations to the OSCE and the Council of Europe, as well as those written in the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement between Moscow and Brussels. Second, European countries are advized to pass their own versions of the Magnitsky list. In Ryzhkov's words, Poles, Dutch, and Britons are ready to consider this option. Third, Europe has to disclose information on 700 billion dollars that the ruling Russian elite either keeps in European banks or invests in villas and castles. Not many Germans were happy to contemplate these aspects though.

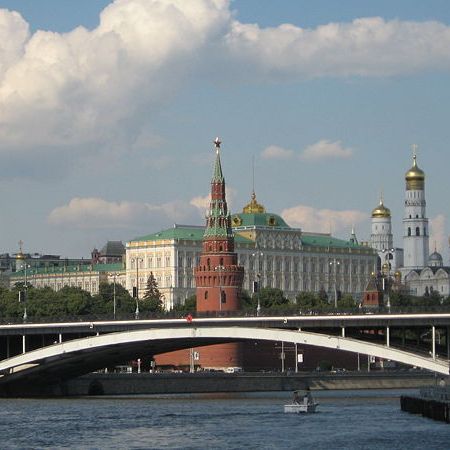

Story 2: The DGAP and the Kremlin

Much of Ryzhkov's pessimism about Putin's regime was in fact confirmed by Alexei Pushkov, the head of the Foreign Relations Committee of the State Duma. He was speaking at the joint discussion hosted by Deutsche Bank and the DGAP think tank.

His speech enshrined all of the nodal points of the Putin discourse—though in a more intellectual form. Of course, he started with blackening the 1990s as a decade of a “weak and thus unpredictable” Russia, perhaps anticipating that Europe should cheer the current Russian “predictability.” Authoritarianism can be either good or bad, he claimed, and referred to “successful autocracies” like Singapore and China (for the later, Pushkov assumed, democratization would be synonymous with its degradation as a world power). “Large systems need centralization. Our rebuttal of liberalism is due to the crisis of 1998,” he assured afterwards. Perhaps, he was proud about Russia’s centralization when claiming that federal authorities in the United States are “defective” due to states’ own jurisdiction in what Russia is currently interested most—children’s rights. It was hard to avoid the impression that even while lambasting America, Russia needs America as the most important quilting point of its Western-centric discourse.

Then Pushkov rejected the U.S. characterization of Russia as a regional power; instead he called his country “a pole in a multipolar world,” yet without global ambitions (and thus without responsibility). Europe, in his view, is deeply disappointing: “what I see here is total ideology, like in the USSR, and no pluralism whatsoever.” Perhaps, something is wrong with the optics?

The West, in Pushkov’s vision, is violent: “We saw blood when the police protected the NATO summit in Chicago against protestors, and force applied against the Occupy movement.” Against this terrible background, the police in Russia looks harmless: “it is afraid of using force.” Nice to know.

The message was clear: don’t meddle in our affairs. But the logic is weird: “Even if we understand that we need to change something, we won’t do this only because we are pressurized” (for this kind of statement there is a Russian saying “I will freeze my ears just for spite”). In another utterance: “If in your own country kids die, it is not a reason for disregarding similar incidents in other countries.” Perhaps, but I personally thought this is first of all the reason to prevent children from dying in Russia itself.

On other issues, Pushkov’s answers were evidently not meant to bridge communicative gaps. Rehabilitation of Stalin? “This is an invention of journalists.” EU normative standards? “In Portugal there are mass-scale violations of pensioners’ rights due to budget cuts.”

Pushkov’s speech was revealing in a sense that he didn’t even try to hide the depth of normative disagreement between the Kremlin and Europe. Yet Russia, as a defender of Portuguese pensioners or as a global beacon for Christianity, looks simply ridiculous. So are Russia’s attempts to portray itself as a country bravely fighting with a unipolar world, something which ceased to exist, in Pushkov’s own words, about a decade ago, and evidently as a result of Russian efforts, but because of exhaustion of U.S. resources. Perhaps, pretending to contribute to this process, Russia feel stronger—but only in its own eyes.

Pushkov and other pro-Kremlin speakers fail to understand why the West won’t cease to be concerned about Russia’s political trajectory. A question from the audience was right to the point: “The German Nazis adopted a law punishing those who live beyond their registered residence by six weeks in prison. Your party criminalized the same misdeed by 3 years. Do you really believe that the EU can abstain from closely watching what is going on in Russia?”

Story 3: The Friedrich Ebert Foundation and a “New Start”

It was really nice to hear some voices of optimism, at last. The seminar “Russia and East Central Europe: a Fresh Start” convened by Friedrich Ebert Stiftung gave such a chance. It called for normalization of relations between Russia and its western neighbors—presumably, under Germany’s informal mediation.

It was nice to hear from Alexander Duleba, director of the Research Center of the Slovak Foreign Policy Association, that Russia is a fully-fledged European country without reservations. It was also good to know that there exists the Center for Polish-Russian Dialogue in Warsaw, which was established to promote a common interpretation of the most difficult issues in bilateral relations. The experience of the Russian–Polish rapprochement is indeed encouraging, but it can’t be easily projected on other countries. Ramunas Vilpisauskas, director of the Institute of International Relations and Political Science in Vilnius, made the Lithuanian position quite clear: Russia has to accept the EU-based regulatory norms in the energy and customs sectors as core conditions for a genuine partnership. Of course, politicians and some experts can keep looking for a magical formula to help East European countries skip political choices, but for Ukraines it is an either–or situation. From the economic perspective, he assured us, there will be no agreement between the EU and the Customs Union, largely based on Kazakhstan’s and Belarus’ non-membership in the WTO. This is a case in point when economics predetermines politics.

Thus, these three episodes provide a good picture of the problems Germany faces in its Russia outlook. Berlin feels increasingly uncomfortable in dealing with the Kremlin, which overtly turns away from a cooperative agenda. German diplomacy looks for new policy options but is obviously not ready to go as far as the Russian opposition calls. The Germans want to keep a dialogue with Putin, but in most cases their endeavors end up with largely symbolic gestures. Many German experts claim that their government lacks a strategy toward Russia, as does Russia. But Germany, at least, cares about what is going to happen next.

Andrey Makarychev is a Guest Professor at the Free University of Berlin, blogging for PONARS Eurasia on the Russia-EU neighborhood.