Russians have endured multiple crises in the post-Soviet period. “Shock therapy” in 1992, the August 1998 default, and the 2008-2009 global recession each had political consequences. Yet, the current economic downturn is different: it is structural, protracted, and unfolding against the backdrop of a global pandemic, which limits governmental instruments to handle the crisis. The simultaneous contraction of supply and demand in the economy coupled with oil price shocks in spring 2020 had multiple economic consequences for citizens: the decline in average disposable income accelerated and reached 8.2 percent in the second quarter of 2020, unemployment peaked at 6.3 percent in October (the eight-years maximum), and the annual inflation rate hit the 4.9 percent mark, above the Central Bank’s target of 4 percent. With an estimated GDP contraction of 3.6 percent and bleak projections of recovery, the state of the Russian economy does not look promising for the citizens.

Despite the apparent negative dynamics in the economy, Russians are hesitant to punish the public authorities politically and, overall, demonstrate loyalty to the regime. President Vladimir Putin’s approval rating plummeted to its record low of 59 percent in May 2020 (far below his long-term mean of 74 percent), only to rebound to 69 percent in September. The federal government’s net approval became positive after Dmitry Medvedev left the prime minister’s office in January 2020. The United Russia Party, which had ratings hovering slightly over 30 percent throughout 2020, managed to dominate regional elections. In other words, Russia’s political elites seemed to have weathered the political consequences of the crisis reasonably well, avoiding political responsibility. Or have they? In this memo, I examine the results of an original survey conducted in June 2020 to reveal the peculiarities of responsibility attribution for the crisis.

The Economic Crisis and the Public

No government escapes the consequences of economic downturns. According to the World Bank, the COVID-19 pandemic has put enormous strain on states and societies worldwide, throwing the global economy into the deepest recession since World War II. For Russians, the pandemic exacerbated existing problems in the economy. In spring 2020, the country’s structural dependence on hydrocarbon exports and the global oil trade collapse severely reduced revenues. Increased capital outflow and high volatility on global financial markets depreciated the ruble against international currencies. The ruble reached 76 per dollar in early December 2020 compared to 64 rubles-per-dollar one year earlier.

The government reacted to the crisis with a fiscal stimulus of about 4 percent of GDP channeled to selected households, firms, and social services. Priority was given to preserving public funds rather than engaging in the unconditional disbursement of money to citizens that many developed countries pursued. Experts noted that the total monetary aid to the economy was lower than in 2008-2009. Nevertheless, the combination of accumulated monetary reserves, the low share of private consumption in the economy, and anti-crisis policies helped the Russian economy avoid the worst outcomes. On the aggregate level, mass reaction to the crisis looked mild. The weekly Sberbank index of consumer spending plummeted by 33.5 percent in March 2020, only to fully recover by July. The second dive in October-November was not as steep, and by the end of 2020, Russians spent roughly on the same level as before the pandemic.

Public concerns about rising prices, unemployment, poverty, and corruption remained the most salient problems, according to regular Levada Center polls. In August 2020, 61 percent of those surveyed put “inflation” at the top of their list (up 2 percent from the previous year), 44 percent put “unemployment” (up 8 percent), 39 percent put “poverty” (down 3 percent), and 38 percent put “corruption and bribery” (down 3 percent). The economic crisis as a category was a top concern for 26 percent (7th place). Unemployment, however, was the only category affected by the crisis; many lost jobs or faced employment problems. Although the real scale of the pandemic’s impact on employment figures is hard to estimate, Levada surveys show that 17-25 percent of Russians experienced wage arrears between April-July 2020, 28-32 percent had salary cuts, and 26-29 percent suffered job losses.

On the political level, public reaction was even less tangible. The extent of public optimism as measured by the share of those who believe that the country is moving in the right direction dropped 11 percent from February to April 2020 (53 to 42 percent). By August, it had almost recovered. Trust in political institutions remained intact. According to VTsIOM polls, shares of domestic policies’ positive and negative evaluations were almost identical at 30 percent, with a 37 percent peak of negative assessments in November 2020. Frustrations with economic and social policies overshadowed positive assessments, but the gap was never too wide. In short, no major fluctuations in political opinions were detected after the economic and pandemic crises hit the country in March 2020. Other studies have detected some changes. For example, Bryn Rosenfeld and her co-authors found “cracks in the popularity” of Putin, and some polls revealed growing frustrations and readiness to protest. Nevertheless, it is unclear if dissatisfaction among Russians is due to economic change or disillusionment with the government.

More importantly, Russians rarely took action against the restrictions put in place by the government. Calls on Internet forums and spontaneous movements such as the one in Vladkikavkaz in April 2020 achieved nothing. The share of those willing to participate in actions or protests to protect their rights and living standards rose from 24 percent in February to 29 percent in July, only to fall to 22 percent by November. Protest campaigns, such as in defense of ex-governor Sergei Furgal in Khabarovsk, or the mobilization to protect the Kushtau shihan (standalone chalk hill) in Bashkortostan, were not related to the economic crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic. It appears that despite deteriorating economic conditions, growing frustrations, and an uncertain future, Russians hesitated to contest the government. Perhaps a natural explanation is that they generally do not connect economic conditions with governmental performance.

Responsibility Attribution in Times of Crisis

To assess if it is true that Russians fail to attribute responsibility for handling the crisis to public authorities, we commissioned the Levada Center to conduct a survey and two focus group discussions on the topic. The survey took place June 27-28, 2020, via phone surveys and employed standard stratified sampling, and was designed to be representative of the nationwide population above 18 years old.

Amidst the pandemic, almost half of the respondents regarded the state of the economy as “average,” 37 percent responded with “bad” or “very bad,” and about 10 percent found the economy to be in “good” shape. For half of the sample, the crisis worsened their households’ economic conditions but did not undermine them. For one-third, the economic crisis did not have any effect at all, but for 15 percent, the impact was dramatic. There appears to be only a weak relationship between assessments of the state of the economy and evaluations of the crisis’s impact. Among those who stated that the crisis did not affect their economic situation, the majority felt optimistic. On the opposite, for those who felt severely affected by the crisis, a little over 60 percent had a “bad” or “very bad” impression of the economy. Those for whom the crisis had an impact but felt it was short of a disaster also tilted toward gloomy assessments. In short, the crisis affected a good share of Russians, but the plurality fared with its impact fairly well into June 2020.

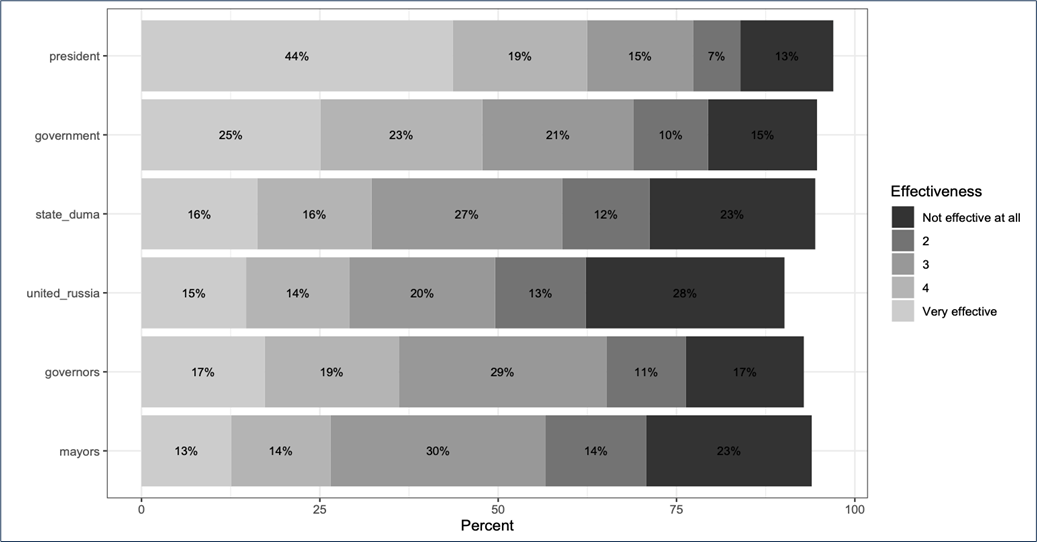

How effective have the public authorities been in handling the economic crisis? Undoubtedly, the majority of Russians believe in the president: 44 percent found him “very effective” while only 20 percent leaned toward “not effective” (see Figure 1). The federal government trails the president, with 48 percent evaluating its performance positively and 25 percent negatively. The ruling party, mayors, and national parliament receive the largest share of negative evaluations (41 percent, 38 percent, and 35 percent, respectively). Essentially, among executives, mayors are the least respected for their crisis management.

Figure 1. Authorities’ Effectiveness in Handling the Economic Crisis

Source: Levada Center Survey, June 26-27, 2020, N = 1622. Percent of NAs not shown.

Similarly, the overwhelming majority attributes responsibility for handling the current crisis to Putin—only 5 percent believe that he is not responsible (see Figure 2). Moreover, 81 percent agreed that Putin bears personal responsibility for handling the crisis, against 17 percent who think the opposite. Mayors and United Russia are the least responsible. The parliament heads the governors by a 5 percent share for being responsible for handling the crisis. In short, most Russians find the president both responsible and effective in responding to the crisis and evaluate the federal government similarly. Russians treat subnational executives as less responsible but also less effective, while the legislative powers are responsible but not very effective.

Figure 2. Responsibility Attribution for Handling the Economic Crisis

Source: Levada Center Survey, June 26-27, 2020, N = 1622. Percent of NAs not shown.

The scales in Figure 2 measure the intensity of the responsibility attribution, but they do not allow for comparing different political institutions. The respondents were asked to evaluate each public institution separately. Unless the survey does not explicitly direct them to rank the authorities, it does not allow us to judge who is more responsible. One way to mitigate this problem is to construct the Comparative Responsibility Index (CRI) proposed by Thomas Rudolph that measures the intensity of responsibility attribution of specific institutions relative to other authorities in the set. Higher positive values of CRI for the president, for example, indicate that the respondents hold this institution responsible and rank it above the other institutions. The shape of the distribution indicates how certain respondents are in their evaluations.

Figure 3 plots the CRI distributions for each institution in the questionnaire. The president and the federal government have similar evaluations with a median score of 5.4. The presidential index is more tight, meaning that the public is more certain about its role in handling the crisis. The State Duma comes third with a median value of 5 and much more uncertainty, the regional executives and the ruling party, United Russia, trail (median 4.2 and 4, respectively). Mayors ranked as the least responsible for handling the crisis. The public, however, remains quite uncertain how to evaluate United Russia and mayors: the interquartile range is 4.2 and 4 points, respectively, as compared to 1.2 for presidential CRI and 1.8 for the governmental index. In short, the CRI confirms that federal executives are distinct from other branches and levels of power: Russians see them as primary institutions meant to handle the consequences of an economic crisis. The public is confused about United Russia’s role even though the party holds the majority in the federal legislature and a vast majority in regional legislatures. Mayors might have been able to evade responsibility because their powers have deteriorated dramatically over the last two decades.

Figure 3. Comparative Responsibility Index Among Different Political Institutions

Source: Levada Center Survey, June 26-27, 2020, N = 1322.

The evidence from the survey defies the idea that Russians do not attribute the responsibility for handling the crisis to the top officials. On the contrary, the real centers of power—the president and the federal government—are almost universally seen as the drivers behind steering the economy away from crisis. Russians are more uncertain about the role of legislative and subnational authorities.

Responding to the Crisis with Political Means

Are Russians ready to defend their standards of living in times of crisis? Table 1 presents the proportions of those who indicated that they would probably take action to defend their economic wellbeing and those who found such a repertoire effective. About a half (49 percent) ticked at least one item from the panel on actions that they would take, and even more (55 percent) found at least one action effective. Signing a petition and contacting the officials were the most frequent possible actions, the latter being most frequently assessed as effective. Voting for the opposition and attending authorized rallies came next. The risky repertoire (unauthorized rally) was willing to employ only 7 percent of respondents, while even fewer believe in its effectiveness.

Table 1. Willingness to Take Actions (to Defend Economic Rights) and Assessment of Actions’ Effectiveness (Percent of the Total)

| Willing to take actions | Find actions effective | ||

| Contact officials | 22 | 26 | |

| Write a petition | 25 | 15 | |

| Attend an authorized rally | 18 | 13 | |

| Vote for the opposition | 20 | 19 | |

| Attend an unauthorized rally | 7 | 5 | |

| Other | 3 | 5 | |

| Do not know | 5 | 5 | |

By these numbers, among those Russians ready to take some actions to protect their economic wellbeing, the plurality prefers a low-cost and less publicly visible repertoire. About one-fifth is ready to punish the authorities electorally; additionally, the same share found this tactic effective. Moreover, among those willing to take action, contacting officials and voting for the opposition were seen as effective: 62 percent in each category versus 52 percent for authorized rally-goers and 39 percent for petition-makers. Public rallies are perceived as less effective in general, and their unauthorized status drastically diminishes their attractiveness as a public protest tool.

The upshot is that, according to the survey, the public’s response to economic hardship is heterogeneous. The majority preferred to do nothing—either because they did not see significant changes in the state of the economy or were satisfied with the president and the federal government’s performance. The plurality, however, is in a darker mood with negative assessments of the economy and some readiness to act. The recent crackdown on public protests surrounding Alexey Navalny will likely reduce support for this type of action. Indeed, Levada Center polls show a drop of 6 percent between November 2020 and January 2021 of those ready to join collective actions with economic demands (from 23 percent to 17 percent). But the aggregate anticipation of protests jumped from 25 to 43 percent, fueled—as I argue elsewhere—partially by speeding inflation and rising unemployment, and partly by exposure to the mobilizations of late January.

Conclusion

Political consequences of complex processes such as the recent economic downturn are hard to grasp when they coincide with extraordinary events such as a pandemic and a volatile international environment. Moreover, short-term outcomes might be different from long-term consequences. So far, the Russian authorities have weathered well the 2020 storm, but Russian society is not tranquil. The rising costs for people to display certain types of political actions might nudge voters to switch to a less costly repertoire, such as voting for the opposition. Given the upcoming parliamentary elections, the stagnating ratings of the systemic parties, and the Kremlin’s obsession with electoral management, tensions over electoral outcomes are likely to increase. Likewise, the economic crisis will not be resolved soon, further aggravating the public mood. It is not the first time the regime faces a combination of challenging factors. However, it is more than ever unclear whether the recipes that have worked so far will remain efficient.

Andrei Semenov is Senior Researcher at the Center for Comparative History and Politics at Perm State University.

Homepage image credit