(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) What do Ukrainians think about the responses of their leaders to the COVID-19 pandemic? How have urban Ukrainians assessed local versus national institutions over these difficult years? To find out, our team conducted a two-wave survey of residents of Ukraine’s cities with populations over 50,000, with each wave following one of Ukraine’s two major lockdown periods, those of spring 2020 and January 2021. This timing also coincides with Ukraine’s ongoing decentralization reform, which enhances the roles of local leaders and institutions. We present data from the 70 percent of respondents who participated in both waves of the survey. In so doing, we shed light on how opinions of urban Ukrainians changed from 2020 to 2021 and raise the question of the effectiveness of federal versus local policy responses in Ukraine. Our findings show that local administrators and family doctors are more valued and trusted than national entities such as ministries and parliament, although the executive branch received respectable marks. Mayors were generally viewed positively, in part, because of the way they defied the authorities in Kyiv.

National Lockdown Policies and Local Resistance

The National Health Service of Ukraine reported about 18,000 COVID-19 cases and about 500 deaths in mid-May 2020. This number increased dramatically to more than 1,000,000 confirmed cases and almost 22,000 deaths by mid-January 2021. Although the central government was relatively slow with testing, coronavirus containment policies were implemented quite rapidly. Initially, a three-week nationwide quarantine was imposed on March 12, 2020, which shut down all educational institutions and classes moved online. Non-citizens were banned from entering the country on March 13, and all national and international air and rail travel was stopped on March 17. A mandatory hospital stay or self-isolation for 14 days was required for everyone entering Ukraine, and wearing masks in public places became obligatory (with considerable fines for violations, up to 34,000 hryvnias, or $1,500). These bans were relaxed only in mid-June of 2020.

Over time, the government introduced more nuanced lockdown policies, such as the so-called “adaptive quarantine” and “weekend quarantine.” An adaptive quarantine offers differential treatments in different regions depending on local COVID-19 patterns and the capacity of healthcare systems. The first adaptive quarantine was introduced in July 2020 and extended until August 31. All regions were divided into zones—green, yellow, orange, and red—based on several indicators, such as the number of coronavirus cases in the last fourteen days per 100,000 people and bed availability at hospitals. Regulations in these zones varied from mandatory mask-wearing in public in the green zones to closing public transport and educational institutions in the red zones. Weekend quarantines were introduced for November 13-30, 2020, that prohibited a range of social and economic activities, including any visits to educational institutions by groups of more than twenty people. Then, due to a transmission spike, Ukraine imposed a new nationwide lockdown on January 8-24, 2021.

Local administrations put up significant resistance at times to the constraints, challenging the central government in the context of the ongoing reform of decentralization. For instance, in May 2020, local authorities in Cherkasy partially relaxed the quarantine for businesses ten days earlier than the national government’s schedule. Later, in January 2021, the mayor of Cherkasy again publicly criticized the latest nationwide lockdowns. In August 2020, local authorities in Ternopil refused to acknowledge the governmental classification of their region as a “red zone.” Also, some religious groups declined to follow lockdown policies and insisted that people be allowed to attend church, especially during Orthodox Easter festivities in April 2020. This attitude was salient among believers of the Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) in large urban areas in southern and eastern Ukraine.

Good examples of local resistance can be seen in the public education sphere. According to a resolution by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine (No. 848, September 16, 2020), decisions on whether to close secondary education schools in “red zones” should be jointly determined by special governmental and regional commissions. Thus, once formed, regional commissions insisted on keeping schools open in Ivano-Frankivsk, Poltava, Kharkiv, Khmelnytsky, and Berezhany, even though they were all in “red zones.” In Ukraine, as elsewhere, local administrative, political, and civil society groups often contested the central government’s lockdown policies. This resistance worked in places—some schools remained open, businesses operated as usual, and people attended religious services and cultural festivities.

Surveying Ukrainians and Pandemic-Governance

Our two surveys followed the most turbulent weeks of Ukraine’s two national lockdowns. The first survey, with 1,076 respondents, took place in late May 2020, after the first significant conflicts between national and local authorities over COVID-19. The aforementioned resistance in the city of Cherkasy happened during this tense time. The second survey, with 1,002 respondents, took place in February 2021, just after the second, January 2021 national quarantine. The survey was conducted online. We used the smartphone application Gradus to circulate questionnaires among respondents aged 18 to 60 in urban towns/cities with populations over 50,000. The trends discussed here may therefore not generalize to older citizens or those located in rural areas. Despite this, our data still provide important insights to understand better how Ukrainians evaluated local and national institutions, mostly because the bulk of the “action” happened in urban areas. For this memo, we focus only on the 676 respondents who participated in both waves. In other words, almost 70 percent of the respondents are analyzed longitudinally, allowing us to observe how their opinions changed over time.

Findings

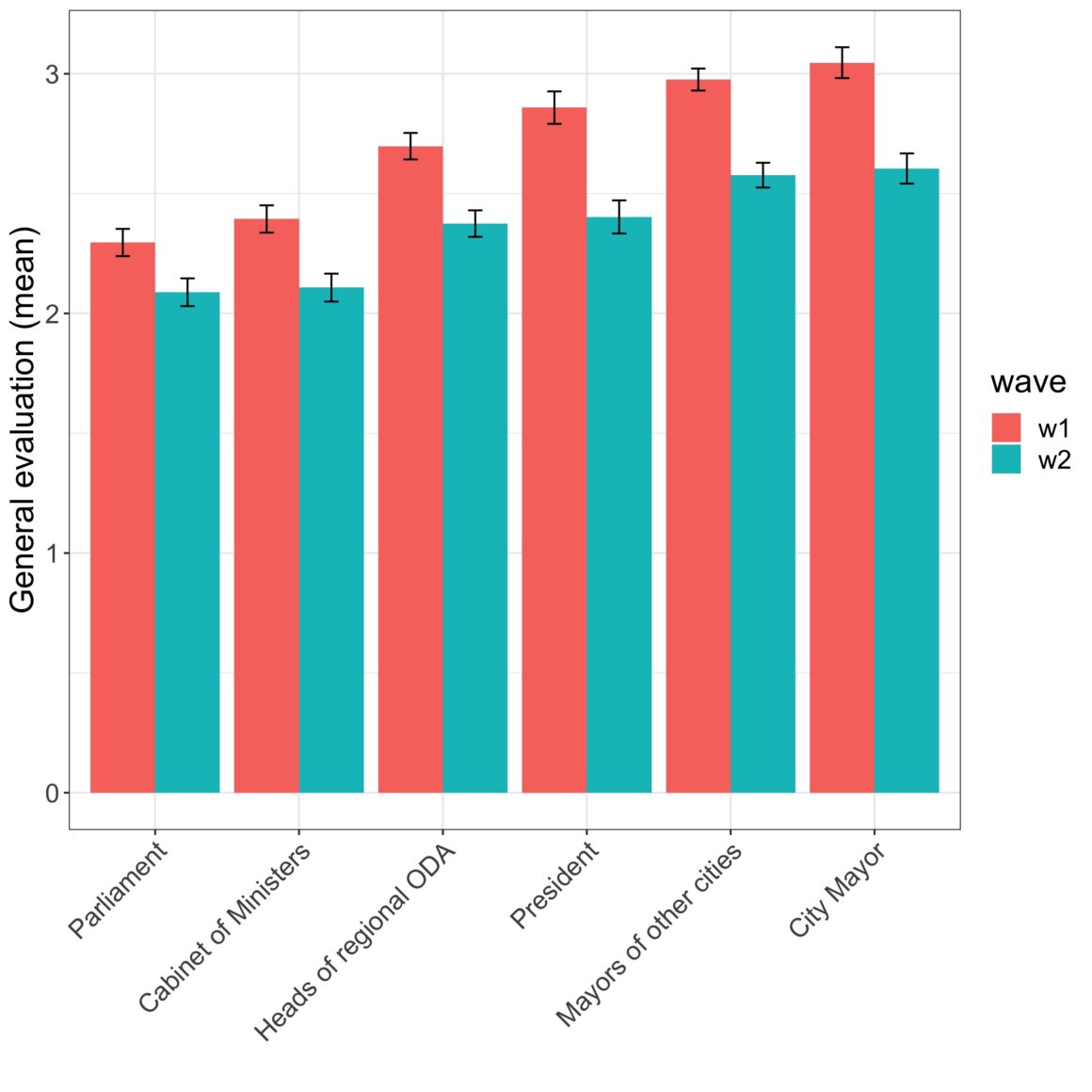

We asked our respondents how they evaluate the actions of the following institutions in fighting the pandemic on a five-point scale, with “1” indicating “very badly” and “5” indicating “very well.” Respondents evaluated national institutions (the Executive, Cabinet of Ministers, Parliament, ministries) and local institutions (administrations, mayors). We included a question about “mayors of other cities” because of significant media attention given to the mayors of Cherkasy, Dnipro, Mykolaiv, Chernivtsi, Zhytomyr, Kropyvnytskyi, and Kakhovka, who together formed a new political party, the Proposition Party, which performed respectably in the 2020 election and which slots with Ukraine’s decentralization initiatives.

Figure 1 shows that local institutions were evaluated better than national institutions. In May 2020, the average evaluation of city mayors was 3, while the average evaluation of parliament was 2.3. The fact that respondents evaluated “mayors of other cities” positively suggests the popularity of leaders of those cities that challenged central authorities, as described above. It was only the president who was able to compete with local political institutions in terms of positive public evaluations. However, results from the second wave of the survey show that over time, ratings of all political institutions declined significantly among the same people. Thus, local authorities cannot necessarily rely on continued popular support during a long-lasting crisis.

Figure 1. Evaluation of Political Institutions on a 5-Point Scale in Urban Areas (N=676)

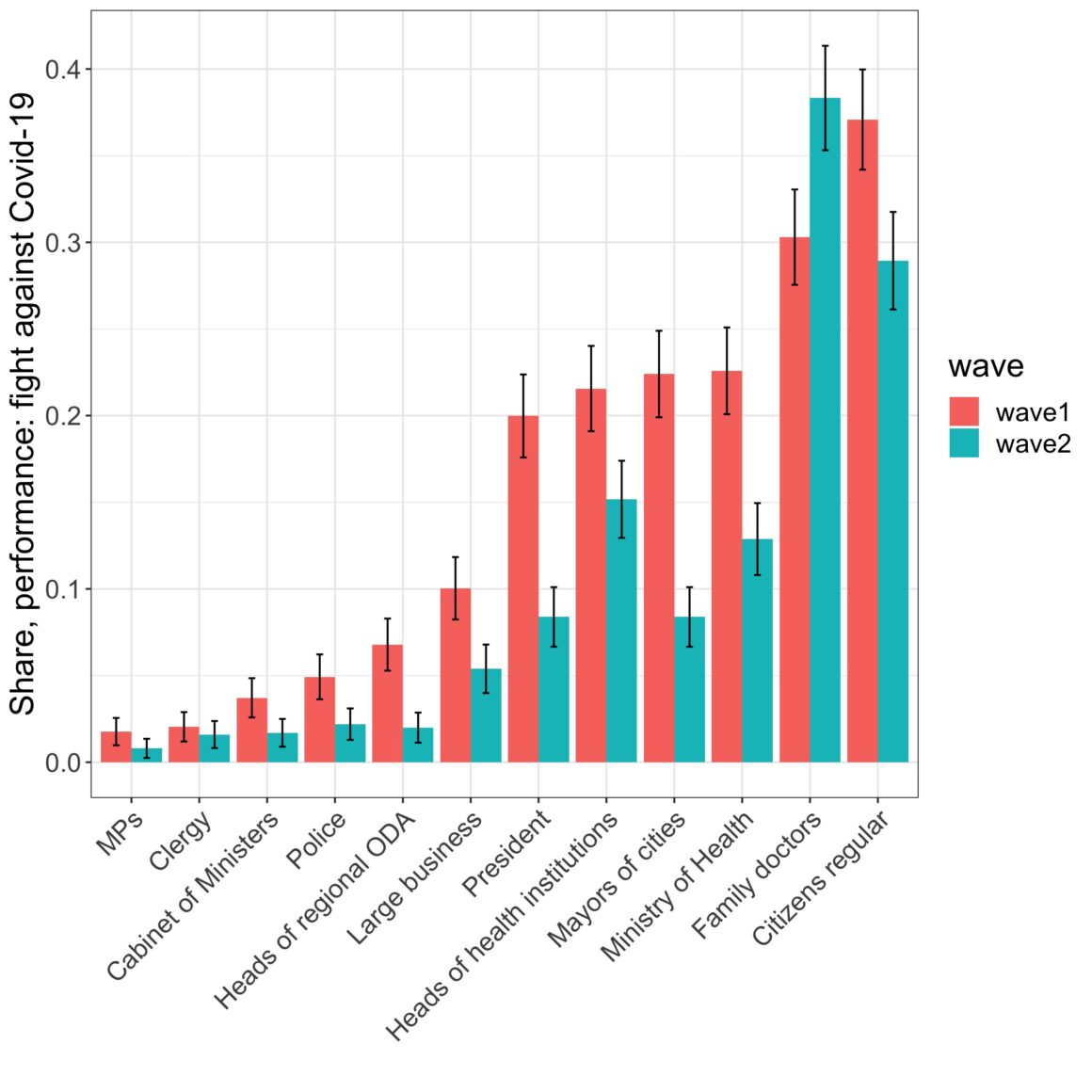

Figure 2. Name All Who Perform Decently in Fighting the Pandemic (Multiple Choice Question. N=676)

We also asked a multiple-choice question in which respondents had to select all institutions or groups that they thought were performing well in fighting the pandemic. In Figure 2, one can see immediately that two groups, “family doctors” and “regular citizens,” were selected by 30 and 35 percent of respondents, respectively. No other groups received similar support. Only 20 percent of respondents named the president, Ministry of Health of Ukraine, and mayors as performing decently in fighting the coronavirus, and very few respondents named any other group or institution. Another noticeable trend observed over time is a significant drop in evaluations of performance in fighting the virus—a twofold decrease in approval of the president, Ministry of Health, and mayors. Even regular citizens received a lower rating in the survey’s second wave. The only group who received a higher evaluation was “family doctors.” The overall indication is that Ukrainians laud the efforts of non-state actors—doctors and fellow citizens—above those of political actors.

Conclusions

What can we learn from these statistics? First, urban Ukrainians tend to give better evaluations to local political institutions than to national ones, with the exception of the executive branch/president. This finding aligns well with the fact that decentralization reform is in progress in Ukraine, making local decision-makers more significant. A positive evaluation of family doctors, which was significantly higher than the evaluation of the Ministry of Health, indicates that, in general, Ukrainians appreciated local responses from health workers. Health reform was a hot and controversial topic during the previous election cycle, and even the role of family doctors fell under criticism by the opposition and some experts. Yet, it looks like in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, Ukrainians were quite satisfied with this institution. Furthermore, our findings about the relatively positive assessment of local political leaders are in line with the observations of other experts, such as Oleksandr Fisun at Kharkiv National University, who note significant political autonomy at the local level. Whether such evaluations were associated with the real performance of local administrations or media discourses are to be investigated after completing a third wave of the survey.

Tymofii Brik is Assistant Professor and Head of Sociological Research at the Kyiv School of Economics.

Elise Giuliano is Lecturer in Political Science, and Director of the MA program at the Harriman Institute, at Columbia University.

PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 737