(PONARS Eurasia Commentary) Reportedly, Armenia is in the midst of a military coup, or is it a counter-coup? What does sociological fieldwork from the city streets tell us? Such methodology was prudently suggested by my wife in 2008 during the post-election protests in Yerevan, which had turned deadly. The current prime minister, Nikol Pashinyan, had been sentenced to seven years in prison after those riots. He served over a year, was released on amnesty, and was even allowed to gain his parliament seat through active grassroots campaigning.

At the time, the typically corrupt and inert post-Soviet presidentialism of Serj Sargsyan sought to bolster its very low legitimacy by allowing a token opponent into the parliament. Pashinyan, or rather Nikol—all leading politicians in Armenia go by their first names, which tells you something about the irreverent political culture—remained a backbencher parliamentarian and public gadfly until the spring of 2018 when a brazen maneuver by Serj to break constitutional term limits produced tremendous political blowback.

Nikol, the loudest Internet populist, helped to instigate and lead the popular protests of 2018, soon becoming himself the head of government. However, he never changed the “undemocratic” constitution that was tailor-made for his predecessor. Now, several years later, it is Nikol who plays the incumbent role. Amid calls for his resignation for mishandling the war with Azerbaijan last fall, he does not seem willing to “surrender” like his predecessor, who stepped down two and a half years ago under pressure. In a novel move, the top brass of the Armenian army joined the chorus calling for Nikol to resign. Is this then a coup? Would we see tanks in the streets?

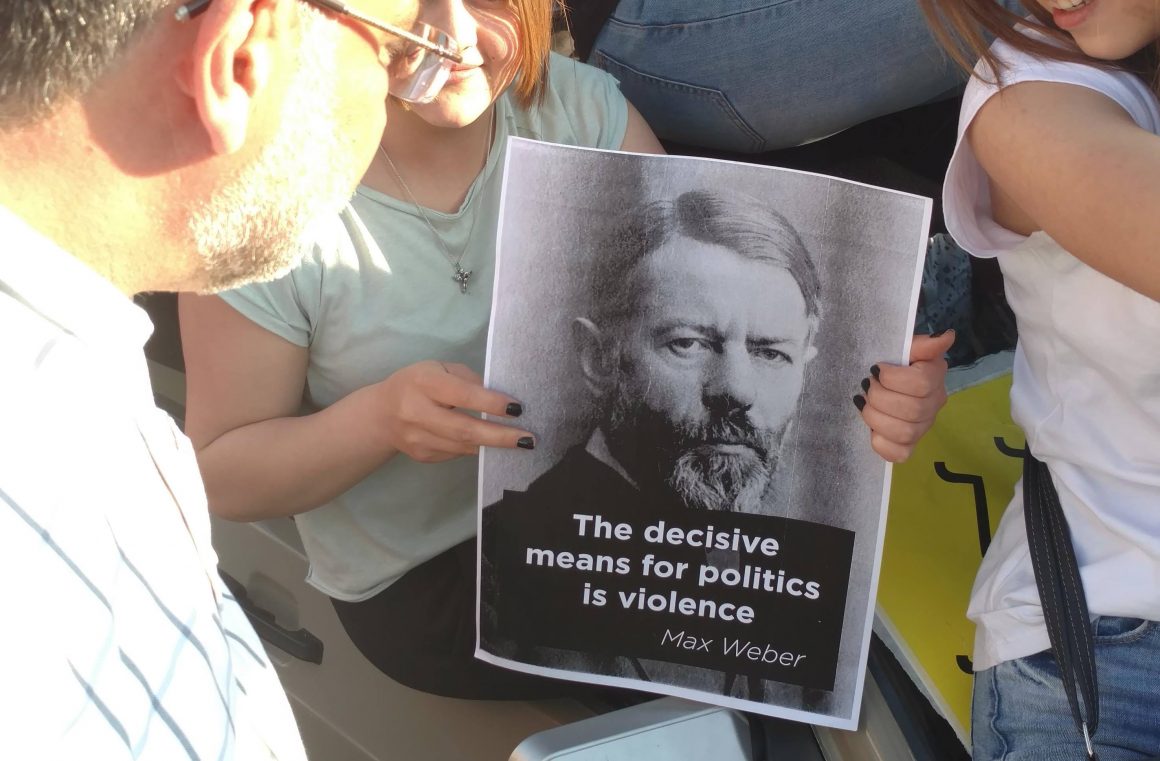

So, every time there are large protests in Yerevan, which is a fairly regular occurrence, I buy a bouquet of flowers for my wife, and, hand-in-hand, we go for a casual stroll, an old-fashioned couple, cordially nodding to men in uniform and protesters. Incidentally, in May 2018, I ran into students brandishing a portrait of… Max Weber! The students recognized me as a professor of sociology and blushed (they were missing classes).

Heads Must Roll?

In recent weeks, I observed two protest rallies simultaneously convene in downtown Yerevan, the opposition and “position,” against or pro Nikol. They stage their rallies barely a half-mile from each other. Curiously, no scuffles took place, none at all. The police were numerous, but they stood and watched. The opposition rally was big by usual standards, probably 15,000 people. Is this the best they could muster? And these were predominantly men in their forties and fifties, very few women, and no youth at all. The crowd looked urban, in a recognizably Soviet way.

The speeches, as always, were delivered mainly by the vociferous and traditionally organized minority of the Dashnaks from under their old red flags with the symbols of a dagger, quill, and plow. Like many things Armenian, the Dashnaks are one of the oldest parties in the world, tracing their lineage to the 1880s Narodniks in the Russian empire. Nowadays, they look and sound much like the Russian KPRF in the 1990s: bombastic, angry, and self-pitying. This protest movement has an exceedingly short program: they are after the head of Nikol for losing the recent war in Karabagh. Hardly any further other programs or demands. The dagger on their blood-red banner invokes the classics: For the sake of the Republic, Caesar must die! The leader of this opposition, however, is Vazgen Manukyan, a dissident intelligentsia demokrat from the times of perestroika, now a bespectacled avuncular figure.

In the main square, a ten-minute walk away, are the Nikolistas. They are perhaps twice as many, perhaps up to 30,000, which is not near their own historical records of 2018-19. But still, a sizable show of numbers at a moment’s call. More diverse, more women, quite a few youths, overall looking more rural or working class. Nikol delivered a rousing populistic speech that is futile to render in a few sentences: We shall not quit in the face of slander! They are the real traitors; their corruption lost the war! I shall face a firing squad right here, in the square, if the People wish so. But who are they to speak for the Armenian people? They are the lackeys of the old regime from which we liberated our nation!

Little substance, but one message is clear: Nikol isn’t leaving.

Police stood idle at the outer perimeter, but it did look like they were doing their job protecting the rally. There was no military presence anywhere, just the loud thunder of Russian fighter jets above the city. The Russians, however, have been doing this daily as part of the anti-Turkish deterrent. Nikol had openly doubted the quality of Russian weapons in a recent interview, which is what had triggered the demand by General Staff commanders that he resign at once. He did not. What are the generals going to do now, or what will be done to them?

In the local bazaar, all shops remain open. Almost all vendors are following the news and the rallies from small TVs and radios. This is arguably not a picture of apathy. They are engaged, worried, but they do not want to join either side. This seems an overwhelmingly common attitude. Raffi, my usual fishmonger and a true maestro of cleaning trout and sturgeon, summed up the attitude despite his terrible stutter: “G-g-georgi, I say, those ‘appazition’ are a sh-sh-sham! I t-tell you! A sham!” He actually used the more colloquial Russian prison jargon for police provocateur, fuflo.

Who’s Worried?

The news of the coup attempt attracted much international, official “concerns,” much more than the actual war last fall. This plays into the hands of Nikol, who suddenly looks emboldened, bristling, and openly threatening his opponents. A street populist, he is in his element now. His tactic is a classic of revolutions: alert the masses to the threat of reaction and old regime restoration, make a call to arms, demand to crush the enemies of the people.

Vazgen Manukian, the distinguished elderly leader of protests, no less openly called on the army to protect the nation and the commanders against the “half-educated, adolescent journalist.” He used many insults of which “milk-sucking infant” (molokosos) was perhaps the mildest. Good calls to mutiny, aren’t they?!

At first, Russia sounded very worried, which the oppositionists interpreted in their favor. Yet President Vladimir Putin has been on the phone with Nikol, which the latter reported over-triumphantly. A mess in Armenia could derail the Russian geopolitical gambit in the South Caucasus. But could it really? Armenia is wholly dependent on Russia for its security in the face of Turkey. Last December, at the Victory Parade in Baku (celebrating the defeat of Armenians in Karabakh), President Recep Erdoğan extolled the memories of Enver-pasha, the leader of a Young Turk triumvirate a century ago and who was chiefly responsible for the genocidal ethnic cleansing of Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians. That message could not be missed in Armenia.

For his part, Armen (President Sarkisyan), another former physicist once at Cambridge and friends with Prince Charles, in the meantime, “conducts consultations with all political forces.” His office announced that the president is allowed three days before signing anything into law.

The protesters set up their tents on the central Baghramyan Avenue, right between the parliament and the Academy of Sciences. The Russian-funded Sputnik news agency, which does not care to disguise their hostility toward Nikol, ran an admiring report from the protesters’ tent camp. Their ironic resemblance to the Ukrainian Maidan tactic is entirely ignored in this case. The details mentioned in the sincerely direct report are wonderfully telling: The heroes had no coffee in the morning because there were no women to serve it. To the question about his occupation in life, an oppositionist calls himself a “professional oppositionist” who had participated in all protests over the years, including the ones which brought Nikol to power two and half years ago. Now he wants him overthrown. A professional indeed.

To sum up, Nikol, despite the war defeat and his dire lack of statesmanship, could still prove his staying power for two reasons. First, formal legitimacy. Second, he can still count on loads of popular support. Even if many common Armenians became skeptical of him, they would rather not support his opponents. Last but not least, Moscow is now taking a rather detached stance on the domestic politics of Armenia. Perhaps they want to avoid escalations like in Ukraine or Belarus. Therefore, the Armenian opposition and “position” are left to sort out their rivalries as loudly as they do it. What suffers in the process is the state legitimacy and coherence, yet neither side can stop now. In effect, this is what alienates a sizable majority of the citizenry. But make no mistake, they are not indifferent or apathetic. They are hoping for a third force, more competent and businesslike. If the popular demand for effective statesmanship comes to pass, Armenia could yet emerge as a path breaker among the post-Soviet countries. Only a hope, so far.

Recommended Alexander Iskandaryan, Director, Caucasus Institute, “Военный не переворот. Почему в Армении не случилось революции [No military coup. Why there was no revolution in Armenia],” Carnegie.ru, February 3, 2021.