(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) The 2016 change of power in Uzbekistan to President Shavkat Mirziyoyev prompted the deepening of cooperation between Washington and Tashkent. While rapprochement touched many areas of bilateral relations, including investments and trade, it is the military-to-military (mil-to-mil) relations that reached an unprecedented depth and frequency of collaboration.

Under Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan has been in high demand as a security partner. Russia has watched U.S. undertakings in Uzbekistan closely, making every effort to present its security cooperation as being more valuable to Tashkent than its partnership with Washington. The United States, however, has a distinct advantage in meeting Uzbekistan’s demands for high-quality professional military education (PME), one of the key pillars of Tashkent’s defense reform. Uzbekistan’s defense establishment is genuinely interested in transforming not only the out-of-date curriculum, doctrine, and training philosophy, but also the modes of thinking and learning in military education. Development of critical thinking through active learning formats—a formula that dominates Western PME—has attracted particular interest among Uzbekistan’s military reformers. This, in turn, offers a unique opportunity to incorporate critical thinking dispositions and methods of interactions between teachers and learners that not only cultivate intellectual interoperability with Western partners but can also potentially diffuse into other social, political, and educational realms. U.S. policymakers should take note of the favorable developments while gauging what more can be done. Such efforts would be particularly advantageous as Moscow and Beijing pursue parallel, ongoing policy gains in Central Asia and directly with the reformist Tashkent leadership.

Mirziyoyev Making Moves

The official visit of Mirziyoyev to Washington in May 2018 opened a new page in the US-Uzbekistan strategic partnership with the signing of the first ever five-year military cooperation plan. A flurry of military exchanges and meetings followed. In November 2018, the Uzbek Ministry of Defense hosted a U.S. military delegation in Tashkent. General Votel, then the commander of U.S. Central Command, made several visits to Tashkent during the same year. In January 2019, Uzbekistan’s special forces participated in their first joint exercise with the U.S. National Guard in Mississippi and an Uzbek delegation visited the headquarters of U.S. Central Command in Florida. In July 2019, the Acting Secretary of Defense Mark Esper hosted the new Defense Minister of Uzbekistan, Major-General Bakhodir Kurbanov, and more visits are planned for the near future.

Skeptics of the new strategic partnership between Washington and Tashkent may dismiss these activities as Uzbekistan’s balancing act and point out the fact that Russia and Uzbekistan signed a military-technical cooperation agreement in 2016, soon after Mirziyoyev became interim president. This document laid ground for negotiations and eventual agreement to procure Russia’s Mi-25 helicopters in 2017. Uzbekistan held its first joint military exercise in 12 years with Russia in October 2019. It remains part of a joint air defense system of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and has recently signed another security cooperation agreement with Moscow that permits the joint use of airspace by the countries’ military aircrafts. In addition to Russia, Uzbekistan has expanded its military cooperation with a number of other states, including Turkey and China.

Uzbekistan’s Military Cooperation

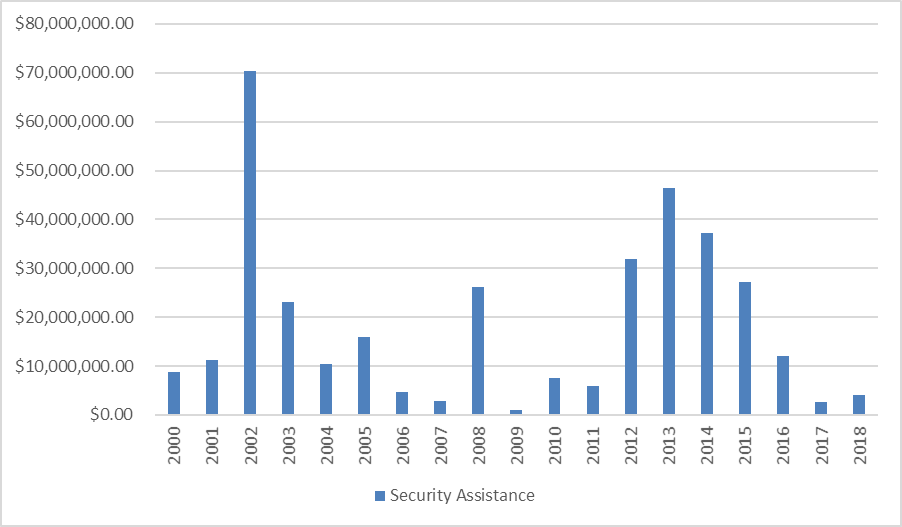

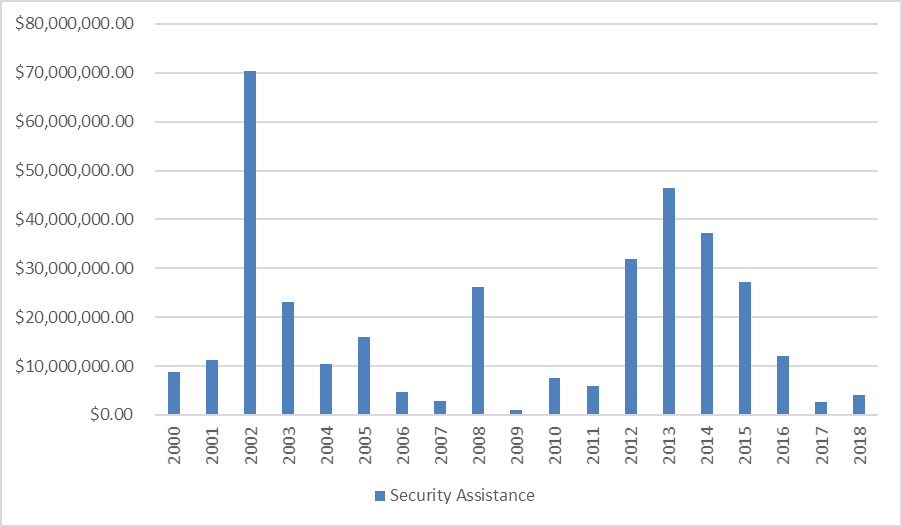

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan inherited the largest military in Central Asia, if still underfunded and clunky. Given the strong Soviet legacy and the presence of a considerable contingent of Russian officers in Uzbekistan’s military cadres, Tashkent initially collaborated closely with Moscow. This changed by the mid-1990s when Uzbekistan joined NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) program in 1994 and expanded cooperation with Washington and several European capitals. The United States began providing Uzbekistan with various forms of non-lethal security assistance and training through the U.S. Foreign Military Financing (FMF) and International Military Education and Training (IMET) and various counterproliferation and counter-narcotics initiatives (see Fig. 1).

U.S. assistance to Uzbekistan increased in 2002 following the opening of the Karshi-Khanabad base and parts of the logistical supply route in support of the U.S. and its allies’ military efforts in Afghanistan. Capitalizing on this expanded partnership, then-Minister of Defense Kadyr Gulyamov launched a series of army modernization reforms aimed at creating a smaller, more mobile, and professional armed forces. Gulyamov was purged from his office along with several other military brass in the aftermath of the Andijan events in May 2005 that marked the beginning of a period of isolation of Uzbekistan from the West. The United States suspended most of its assistance to Tashkent and withdrew its troops from the Karshi-Khanabad base at the request of former president Islam Karimov. The EU suspended the sales and transfer of arms and other types of military equipment to Tashkent.

Figure 1: U.S. Security Assistance to Uzbekistan

Source: Security Assistance Monitor. This is a total of all security assistance programs funded by the U.S. Department of State and Department of Defense.

In 2005, Uzbekistan’s military cooperation pendulum swung toward Russia and China. However, Tashkent continued slow military modernization along Western paths and resisted greater integration into the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organizations (CSTO). During this period, Uzbekistan revamped its military command and control structure and launched reforms of the border guards. The thaw in Uzbekistan’s relations with the United States began in 2012 following the lifting of sanctions by Washington. In the following years, the Obama administration increased the volume of military assistance to Uzbekistan to the levels received by Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan citing the need of enabling Tashkent to counter terrorist threats to the logistical supply lines to Afghanistan.

Mirziyoyev put Uzbekistan’s limited participation in defense consultations with the United States and NATO on the fast track, driven by the goal of military modernization. The new Military Doctrine of 2018, with its full contents openly published for the first time, signaled a transparency in Uzbekistan’s defense policy and need to communicate its security priorities to its partners and neighbors. The three main priorities of the military reform include: (1) rearming the military with modern weapons and equipment; (2) developing a domestic defense industry; and (3) reorganizing the armed forces. The latter includes changes to the soldiers’ training system, boosting troops’ benefits, and development and implementation of new guidelines and processes for educating servicepeople and officers. Much more emphasis is being placed on the physical and psychological health of the troops and their patriotism. For the first time, for example, Uzbekistan is bringing a professional food service to the military, replacing the old Soviet approach that made the troops responsible for preparing their own meals.

Reforming Professional Military Education (PME) in Uzbekistan

Similar to other post-Soviet republics, Uzbekistan inherited an entrenched legacy of Soviet education expressed in the prevalence of ideologized content, emphasis on the passive reception and memorization of material transmitted in a lecture format, and the lack of diversity of thought. While the Karimov government undertook steps to reform and expand the structure of military educational institutions, its core curriculum and instructional approaches remained intact.

Things began to change slowly in 2012 when Uzbekistan reached out to NATO with a request for assistance in the PME through the Defense Education Enhancement Program (DEEP) Initiative. A one-of-a-kind program, the DEEP was designed to offer “demand-driven” curricula (what to teach) and support in faculty development (how to teach) to individual countries in order to professionalize their officer corps, non-commissioned officers, and civilian defense officials and make their PME compatible with Western education strands and values. Launched in 2007, the DEEP has provided PME support to Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Croatia, Georgia, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Mauritania, Moldova, Mongolia, Serbia, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

The DEEP Program in Uzbekistan began with modest initiatives that sought to augment its professional military curriculum with the topics of civil-military relations and lessons from U.S./NATO experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan. Mirziyoyev and his defense team took more concerted, wide-ranging, and qualitatively different steps to create a unified system of PME in the republic. In 2016-2017, the Uzbek side invited a Military Education Adviser at the Uzbek Ministry of Defense to serve as a resident adviser at the Armed Forces Academy of Uzbekistan (AFA). Originally established as an inter-service educational institution that prepared Uzbek officers for higher level leadership positions, the AFA was transformed into a premier institution of PME in Central Asia. Located at a new, modern, and technologically advanced campus in Tashkent, the AFA was designated the central position in Uzbekistan’s military college system and a leader in military education reform.

The last two years have seen a remarkable transformation in the priorities of Uzbekistan’s PME that could be witnessed in the selection of DEEP events, the choices of sites and types of engagement requested by the Uzbek visitors in the United States, and conversations with Uzbekistan’s military faculty and professionals. The recent DEEP events, for example, have focused on adult education theory and practice, interactive learning methods, simulation exercises, and lesson plan development and assessment. During his July 2019 visit to the United States, Defense Minister Kurbanov toured the Defense Language Institute at the Joint Base San Antonio (Texas), where three Uzbek officers are learning English, the Columbus Air Force Base (Mississippi), where an Uzbek pilot will take part in the Aviation Leadership program, and the National Defense University in Washington, D.C., which invited an Uzbek officer for a 10-month-long program at the College of International Security Affairs (CISA). The Ministry of Defense delegation expressed interest in learning about ways of integrating civilian agencies into military education, active learning methods of instruction, and approaches for developing faculty teaching competencies reflecting Western and NATO standards.

The level of PME transformation in Uzbekistan, of course, depends on whether its government and military institutions will be able to operationalize and internalize changes derived from the conduct of DEEP activities. To date, the Uzbek side has shown considerable interest and enthusiasm in modernizing its military education. It has also made significant strides in modernizing its army and maintaining combat readiness. The U.S. Department of Defense has also been receptive to this quest for changes. The Defense Ministry’s position has been recently extended for another two-year period, and the U.S. PME institutions have developed lines of cooperation with the AFA.

Yet, more can be done to capitalize on this mutual interest in PME reform and mil-to-mil collaboration. The U.S. government should make an effort not only to harmonize the existing military education and training efforts with the DEEP events but also to expand them. In 2018, only 19 Uzbek officers received military training from the U.S. military. Between 2010 and 2015, the number of Uzbek trainees ranged from 67 in 2010 to 425 in 2015. Only 6 trainees participated in the DEEP events in 2015. The majority of Uzbek officers took part in short-term counter-narcotics exercises and courses in their home country with less than 2 percent of U.S. security assistance allocated toward the IMET. However, it is the U.S.-hosted long-term military educational exchange programs, like the IMET, that have been linked to positive improvements in democratic institutions. The arms-sales programs, on the other hand, have been ineffective at improving human rights or democratic prospects in those countries that purchase U.S. weapons and services. Given the Trump administration’s transactional approach to foreign policy premised on a constant exchange of valued resources, such as modern military equipment or foreign direct investments, the emphasis of security assistance to Uzbekistan is likely to shift from military education and training programs that emphasize comprehensive curricular development and faculty development to short-term ad hoc training courses and military sales. The Trump administration has made selling American defense goods to foreign partners a key priority of its security assistance and has hoped to boost arms sales in Uzbekistan. Such a shift, however, may slow down the achievements in Uzbekistan’s professional military education.

Conclusion

In the long run, military education and training programs can accomplish numerous shared goals with lesser costs. First, Uzbekistan’s teaching faculty would be able to sustain its own academic programs, ensuring continuous professionalization of the military. Second, the armed forces will become more capable of conducting their own independent actions domestically and providing security leadership in the broader Central Asian region. Third, the comparability of PME standards and joint training will strengthen the interoperability of the Uzbek troops with the United States and NATO. This will open a possibility for the Uzbek armed forces joining the allied troops for peacekeeping or other operations. Lastly, the politics and society of Uzbekistan can also benefit from changes in the quality of military education. Research has shown that professional militaries educated and trained based on Western standards are less likely to commit human rights abuses in conflicts. A professional army will contribute to establishing greater trust between Uzbek citizens and state institutions and increase the stature of the military profession in Uzbekistan.

Mariya Y. Omelicheva is Professor of National Security Strategy at the National War College of the National Defense University. Disclaimer: the views expressed in this paper are solely the author’s.

[PDF]