With well over a year of large-scale and highly destructive warfare already passed, Ukraine has embarked on an ambitious effort to restore and enhance its economic potential, even amid the continuing military struggle to force the Russian army out of its sovereign territory. A year ago, we (Clem and Herron) published a PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo on the extent to which Ukraine’s regions (oblasts) and the city of Kyiv had already become significantly stratified along socioeconomic lines prior to the outbreak of the present war with Russia in February 2022. As we explained, in terms of productivity, some areas clearly outperformed the national average while others lagged behind. We suggested that, when undertaken, reconstruction efforts ought to be guided to some extent by the existing regional economic landscape to take into account economies of scale, existing domestic and foreign trade linkages, and established supplier and distribution networks.

Now, with updated regional data (for 2021) on the situation just before major hostilities commenced in 2022 and initial estimates of war damage as of early 2023 in hand, we have enough information to allow for a more refined look at the prospects for territorial development going forward. As we make clear here, the regional development challenge is now considerably more fraught than it was prior to the ongoing war owing to the much greater damage done to many of the country’s most economically vital areas.

What Goes Where?

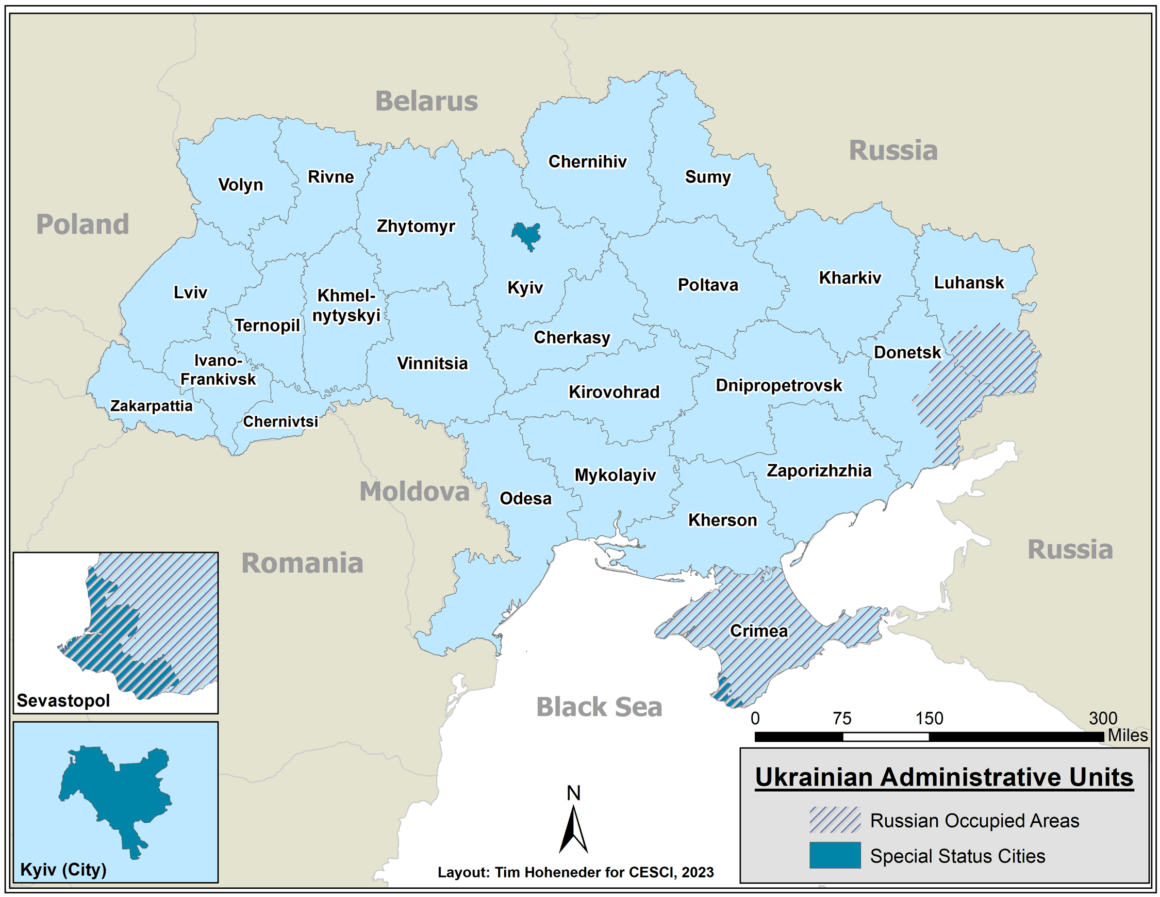

Reconstruction is crucial to Ukraine’s aspirations to be a viable EU member should it gain admission. Entry would provide adequately for its citizens and be a basis for a strong national defense in the future. But the task at hand is enormous both in societal and economic terms. As what has lately been termed the “world’s largest construction site,” Ukraine has considerable capital for rebuilding already in hand or on the way from international donor agencies, states that back Ukraine in the war against Russia, and domestic and foreign business interests. Choices as to what uses these monies should be put are already up for discussion. Importantly, however, where among Ukraine’s regions (see Figure 1) that funding should be directed is usually not addressed, despite the fact that its economic geography, which is anything but uniform, is a crucial element in what will be a long recovery process.

Figure 1. Regions of Ukraine as of 2021

Allocating funding or directing investment regionally is never easy because, inevitably, there are not enough resources to do everything, and tough decisions must be made as to which priorities take precedence. Certainly, there is general agreement that the top priority should be restoring and expanding the capability of national, regional, and local entities to provide social goods such as healthcare, housing, and education (state capacity). This is important both on humanitarian grounds and as an investment in economic growth, as such social goods would help to improve the health and skills of the workforce. These and other societal deliverables, often called human security, are also elements of an expanded definition of national security. However, when seeking to maximize economic growth per se, other considerations, especially geography, come into play.

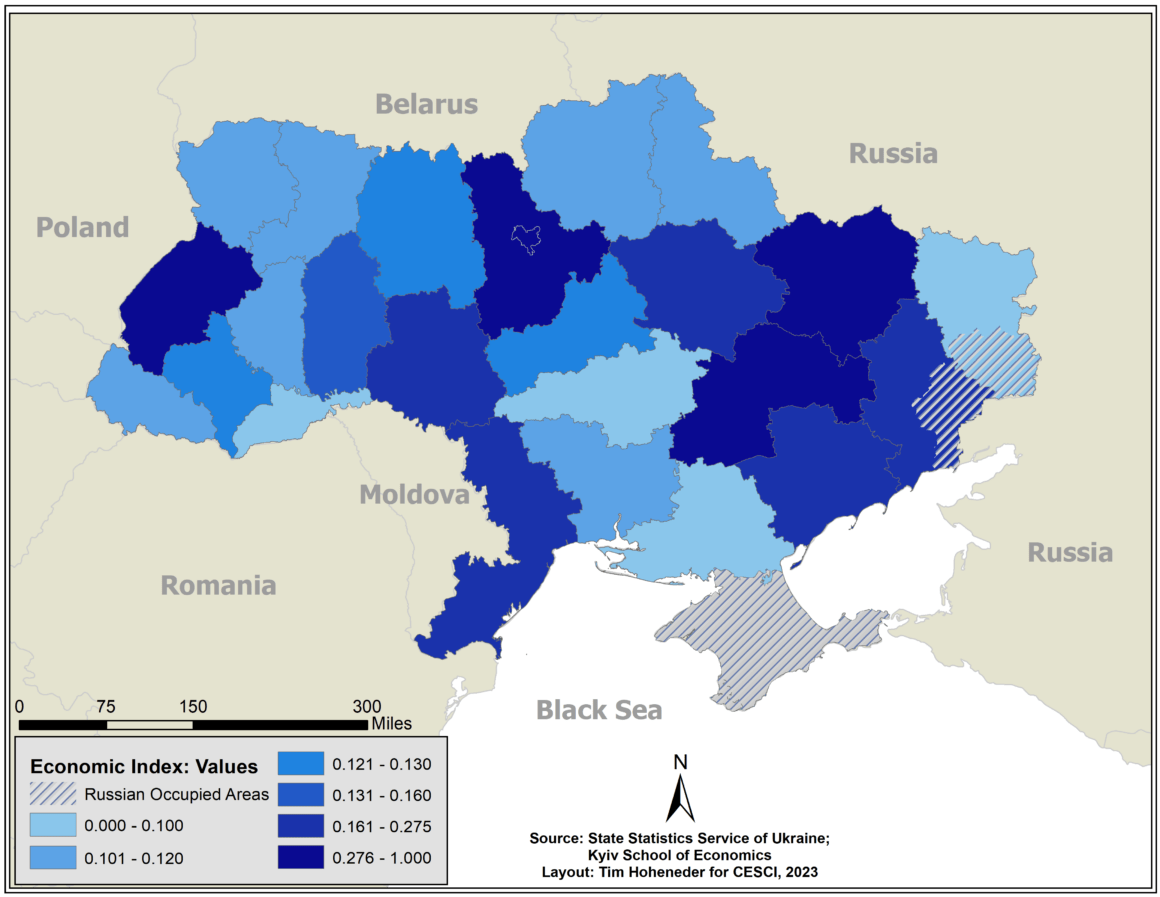

To assess the economic landscape on the eve of the latest Russian invasion, we compiled a normalized rank-order index of the newly available data (2021) on each region’s share of gross domestic product (GDP), national capital investment, and budget revenues (see Figure 2). Of particular interest is the fact that just four units (Kyiv City and Dnipropetrovsk, Kharkiv, and Kyiv oblasts) accounted for 45 percent of Ukraine’s GDP and ranked in the top five regions in terms of our economic index (the other being Lviv oblast) (see Figure 2). Also of note is that Donetsk oblast ranked sixth, despite being partly occupied by Russia after the initial Russian invasion in 2014, due in large measure to the vast metallurgical complex in and around then government-controlled Mariupol. Such a skewed distribution of national economic activity is not uncommon; in the United States, for example, 41 percent of GDP is accounted for by just five states (California, Texas, New York, Florida, and Illinois).

Figure 2. Ukraine, Economic Index, 2021

Yet, given the destruction caused since early 2022, there are even more serious questions about where state development money should be directed among Ukraine’s oblasts and the city of Kyiv or encouraged in the case of private capital to maximize return on scarce financing. It still remains true that a major consideration in the case of Ukraine in formulating regional investment strategies is the economic landscape antebellum. Ordinarily, one would expect that regions with a highly developed infrastructure, domestic and international trade linkages, a skilled workforce, and an array of interlocking suppliers and manufacturers would, to a significant extent, be preferred locations for further investment. As we suggested in our earlier piece, in large measure, this would have meant encouraging further growth in rising regions, assuming, as Niles Hansen reminded us many years ago, that diseconomies of scale were not yet problematic.

But in the case of Ukraine, as the war progressed, the concentration of the country’s economy in these particular regions made for strategic vulnerability vis-à-vis Russia that became all too evident once full-scale warfare commenced. Rapid advances by Russian forces in the direction of Kyiv, Kharkiv, Sumy, Poltava, Chernihiv, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, Mykolaiv, and Kherson oblasts in early 2022 and the resultant bombardment and devastation wrought in these areas—even though much of the Russian gains were later recaptured by Ukrainian troops—caused severe damage to economic and social infrastructure, not to mention many civilian casualties. As has been true since the 2014 Russian invasion, societal infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, and clinics have been targeted by the Russian military. Despite heroic efforts on the part of Ukraine’s infrastructure workers (i.e., the electrical power, roads and railroads, and telecommunications operators), civil defense personnel, and ordinary civilians to maintain some sense of normalcy, the country’s economy has been seriously degraded by attacks on leading centers of production.

A Landscape Turned Black

Considerable research is now available that provides a preliminary and appropriately caveated assessment of the extent to which the war has destroyed or damaged social and economic capacity across Ukraine. An ongoing compilation of war damage is underway at the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE), with estimates of the extent of damage or destruction among Ukraine’s regions. The World Bank has also published detailed information on conflict-related damage by region and economic sector. Recent reporting from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project enables large and small-scale mapping of incidents or attacks. Data compiled by Osprey Flight Solutions, an aviation consultancy, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) allow us to visualize targets hit by Russian missiles and drones throughout Ukrainian territory. Finally, analyses of war damage by sector enable a more comprehensive assessment of Ukraine’s longer-term challenges during and after the conflict.

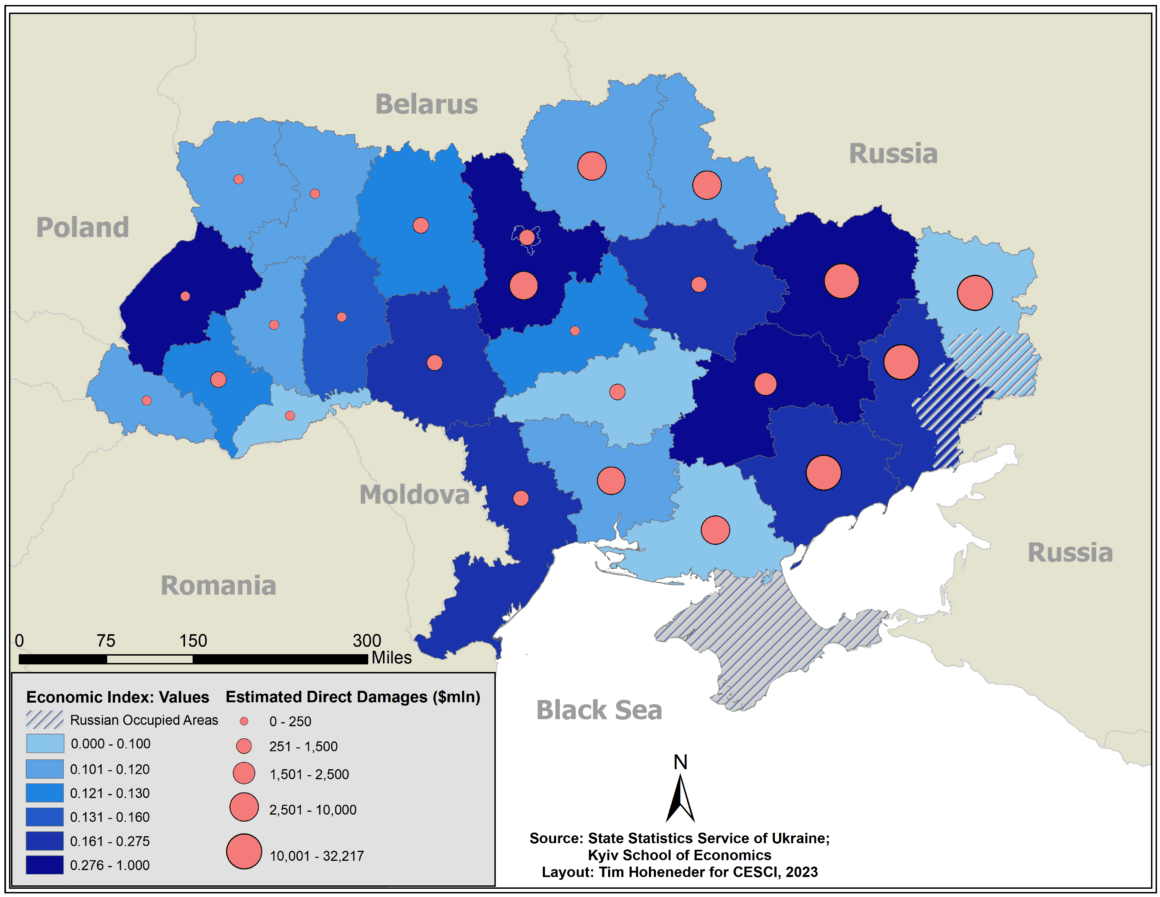

For an overview of the spatial impact of the war at the regional level, we overlaid the KSE damage estimates on our regional economic capacity index (see Figure 3). Not surprisingly, the oblasts bordering Russia and, to a lesser extent Belarus (from which Russia also launched attacks) took the heaviest brunt of the fighting in material terms, whereas areas in the central and western parts of the country were relatively unscathed. Of the five most seriously damaged oblasts, Kharkiv and Kyiv were also among the top five economically most productive regions before the 2022 war (and Donetsk was sixth). Of the other top five producing regions, Dnipropetrovsk oblast and the city of Kyiv absorbed significant damage, while Lviv oblast, the furthest removed from the fighting, suffered comparatively little. The World Bank’s estimates of damage by region match these KSE rankings.

Figure 3. Economic Index (2021) and War Damage Estimates (2023)

More detailed incident reporting also allows for a closer examination of the extent of damage within oblasts that have been attacked and how that might play out as reconstruction proceeds. ACLED data make plain that Russian attacks had the most severe impact along the battlefront itself. For example, in the Donetsk region, the heavy fighting in Mariupol wrecked two of the country’s largest steelworks and contributed both to the region’s high damage rating and to the drop of 40 percent in steel production nationally. Also, many of the longer-range missile and armed drone attacks hit important targets in regions that were otherwise not heavily damaged.

The Difficult Road Back

As long as regions within Ukraine that border or are near Russia remain highly vulnerable to attack by Russian forces, more thought must be given to expanding economic capacity and supporting infrastructure in the central and western parts of the country; that is, beyond the range of artillery and rocket attacks along the battlefront. As stated above, this certainly does not mean that restoring social capital in war-ravaged regions ought to be ignored. Indeed, the KSE data indicate that over half of the damage incurred as of February 2023 was to housing, most of which occurred in regions closest to Russia. As we noted previously, when surveyed in December 2022, Ukrainians ranked the restoration of the country’s housing inventory as the second reconstruction priority, behind only ensuring energy supplies, an opinion that held country-wide.

But it is clear now that fixing and expanding the country’s jobs-producing business/enterprise base, which absorbed about 11 percent of damage, should involve some degree of spatial realignment towards regions that are relatively safer from large-scale Russian attacks. While again acknowledging that longer-range Russian missile strikes have occurred country-wide, the damage that they have done, evident in Figure 3, is far less than in the eastern and southern oblasts where the heaviest ground fighting occurs.

Although we are not able to assess the war’s impact on Ukraine’s large agricultural sector in each region (8.7 percent of total damage), it is also concentrated in the areas where heavy fighting has taken place. Of the top ten oblasts in sown acreage, six have experienced the worst direct effects of war. Damage done to fields, crops, machinery, storage facilities, and livestock has been severe, not to mention the threat of landmines and unexploded ordnance remaining. This compounds the damage done to manufacturing and service industries in the most heavily affected regions.

Among the many challenging facets of the restoration project for Ukraine will be encouraging much higher levels of foreign direct investment (FDI), which has been very low heretofore. It is reasonable to assume that investors will take into account the potential vulnerability of facilities that they fund. Although it is far too soon to make any definitive judgments regarding regional investment since the onset of war, there are early indications that some new capital is being directed westward, that is, further from the Russian threat. This is not to say that building new plants in war-damaged regions is necessarily ill-advised. The lure of regions with dense networks of suppliers and consumers will still be attractive, as evidenced by Unilever’s recent investment in the Kyiv region.

However, harbingers of further development in the west stem from the announcement by Nestlé that it will build a new facility in Volyn oblast, the recent notice concerning new Westinghouse nuclear reactors in Khmelnytskyi oblast, Bayer’s planned investment in Zhytomyr oblast, and the decision by Kharkiv-based Suziria Group (a major producer of pet foods) to build a new plant in Ivano-Frankivsk oblast. The Lviv IT complex, “Ukraine’s Silicon Valley,” has been especially active in attracting new funding and is, again, far removed from the battlefront.

Conclusion

It is instructive to consider the tragedy that has befallen Kharkiv city and its environs, which epitomizes the tension between stabilizing and optimizing regional economic options in the wake of the Russian invasion. After nearly succumbing to pro-Russian separatists in 2014, the region was subjected to numerous attacks against civilians and urban areas during the heaviest fighting in early 2022. Several industrial enterprises of national importance were wrecked or damaged, which in turn affected suppliers and consumers and caused yet more economic dislocation. Despite the Ukrainian counteroffensive that forced Russian troops to retreat, strikes against Kharkiv, including its well-known universities and research centers, continued well into 2023. Given its immediate proximity to the Russian border, the region is arguably among the most vulnerable to future attacks under present circumstances and will continue to be so as long as the Russian leadership seeks to seize Ukrainian territory.

Since 2014, new markets for Kharkiv’s large manufacturing firms have been sought in an effort to wean the local economy off of Russian customers, who had traditionally been the primary market for local industry but which will certainly not be the case in the foreseeable future. A determination among the remaining population to rebuild the city, engaging, among other things, one of the world’s leading architects, with an energetic mayor whose goal is not only to rebuild but enhance the area’s prospects, must be respected. But care must also be taken to ensure that the challenges, both locally and in the country as a whole, are balanced in a manner that facilitates Ukraine’s future development and national security.

Ralph Clem is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Senior Fellow in the Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs at Florida International University.

Erik Herron is the Eberly Family Distinguished Professor of Political Science at West Virginia University.

Timothy Hoheneder is a Doctoral Student in the Natural Resources and Earth Systems Sciences Program at the University of New Hampshire.

The authors thank Matthew Lantzy for his assistance.