(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) The Russian Parliament’s 2020 spring session was in many ways both expectedly and unexpectedly historic. It began with a January 15 presidential address to the Federal Assembly, announcing constitutional reforms that involved an overhaul of the 1993 Russian Constitution. The constitutional amendments passed without opposition or significant editing, thereby paving the way for the larger, more detailed work of implementing them into the fabric of Russian legislation. Simultaneously, the new and unplanned necessity arose to implement widespread anti-coronavirus measures, which shaped the Federal Assembly’s course.

The emergency situation served as the perfect cover for legislative plans that were only vaguely, if at all, connected with fighting the pandemic. For example, changes were made to Russia’s electoral laws that, in a different situation, would have attracted more public attention and possibly public protest. Apart from purely political amendments, various lobbying initiatives were quietly passed, such as those involving the construction industry and protected lands. Looking back, Russia’s spring 2020 legislative processes and its results show how parliaments in electoral autocracies such as Russia function in crisis situations. Despite the low media and public attention, we can still identify the variegated political aims of opportunistic interest groups, not just those of the executive or the presidential administration, who use the opportunity to further agendas.

The Parliament in the State of Dubious Emergency

Unlike many other parliaments of the world, Russia’s did not go online/virtual for its day-to-day work. Deputies were present in the Plenary Hall, but there was no access for outsiders to attend sessions or committee meetings or meet and communicate with deputies. It should be noted, however, that the level of electronic transparency of the Russian parliament’s work is relatively high, and it can be followed, and the documents read online. However, this is no substitute for public scrutiny, direct input from independent experts, or on-the-ground attempts to influence the legislative process by means of public advocacy. Parliamentary correspondents and external commentators/experts did not take part. As the coronavirus spread, public attention was elsewhere.

The lengthy and fertile spring session of 2020 started on January 13 and continued until July 26. During that time, the parliament adopted 312 new federal laws, a high but not record-breaking amount. The usual efficiency of a spring plenary session, which is longer than the autumnal one (customarily devoted to the consideration and adoption of budgetary bills), rests between 200 to 400 new federal laws. The largest number of bills considered during any spring session was 620 (2017).

What was unusual in this spring session was the high percentage of legislation introduced by the government (see Figure 1). Unlike the autumnal session devoted to the budgetary process, the spring session is usually more of a playground for deputies’ creativity. Usually, there is a high percentage of bills introduced by parliamentary deputies and members of the Federation Council (upper house).

Figure 1. The Status of Bills of the Russian Parliament in 2018, 2019, and 2020

Source: Russian Parliament/State Duma Electronic Database

How to Change the Constitution Without Attracting Undue Attention

The bills that were considered and then adopted in the spring of 2020 can be divided into various groups. Because the session started with constitutional reform, the parliament had to consider actual constitutional amendments. Every parliamentary bill passes three stages: the first reading approves the general concept of the bill; the second reading introduces the amendments; and the third reading adopts or, in rare cases, rejects the bill as a whole.

It has been a long-standing parliamentary device to introduce key changes during the second readings of an amendment, when initiators do not want to draw too much public attention to their bill. That makes it possible to shorten the process by skipping the first reading phase that, according to parliamentary rules, needs to take thirty days and sometimes lasts longer. The accumulation and discussion of amendments take place within the parliamentary committee responsible for the bill, and these proceedings are much less public and accessible to an outside observer than the plenary sessions. This helps to divert some part of the public attention.

In 2020 we saw this practice on a much larger political scale. The first wave of constitutional amendments introduced by the president into the parliament on January 20, 2020, concerned the composition of state bodies and the checks and balances system between the president, government, Federal Assembly, and higher courts. The “first wave” of amendments also contained some of the social guarantees, like regular indexation of state pensions and salaries, which were and remained, according to polling data, the most recognizable and popular among the proposed constitutional changes.

At the end of February, parliament took on the second wave of amendments, introduced during the second reading of a constitutional bill, because, juridically, all of the numerous amendments, which increased the bulk of the Russian Constitution by 40 percent, were one amendment—one single bill. The second wave of amendments contained provisions that have since been nicknamed “biopolitical.” These concern the preservation of traditional families, the defense of children as one of the main priorities of state policy, mention of belief in God as having been inherited from ancestors, and a mention of the Russian people as a state-building (state-forming) nation. These amendments had an evident conservative slant and were, in all probability, aimed at giving more of a “human interest” to the approaching constitutional voting by reinventing it as some sort of a referendum in defense of traditional values, thus strengthening voter turnout.

On March 10 came the third, last and final amendment phase—called “the grandmother’s clause” or “Tereshkova amendment”—that entailed the zeroing-out or resetting of presidential terms, which in hindsight looks like the main reason for the whole constitutional reform. However, we do not have grounds for affirming that this idea originated from the start of this legislative campaign: the development of the amending process as delineated above rather lends itself to the logic of tactical political necessity rather than showing signs of a well-laid plan. The “checks and balances” part of the amendments were designed to legitimize the political practices and re-distribution of power of the last fifteen years while additionally guaranteeing the future successor’s position against a potentially oppositional parliament and a hostile higher court by curtailing their powers and severing the dependence between the parliament’s approval (or the risk of early parliamentary elections) and the appointment of the head of the government.

The need to additionally legitimize this de facto new version of the constitution brought on the idea of a national vote, which is not a referendum but an ad hoc plebiscitary procedure that, nonetheless, requires strong voter turnout to compensate for the laxity of its rules. The general voter, while approving of the social guarantees promised in the amendments, was not interested enough in the “checks and balances” part of the package to whip up some sort of civic enthusiasm and mass voter participation. Hence the second wave amendments catered to the taste of the conservative part of the electorate and gave the whole heterogeneous mass of amendments some semblance of ideological unity.

This unity, however, presented the next problem: the amendments as a whole, with their administrative, social, and ideological components, began to be perceived not just by members of the “commentariat” but by the ruling elites themselves as a kind of “political testament”[1] from a president who truly intends to leave by 2024. To prevent, as President Vladimir Putin himself called, the “eyes-shifting” search by elites of the next Russian ruler, extraordinary changes were implemented to the constitution, giving the president the option (but not the obligation) of running for office again. [2]

The role of parliament in the consideration and adoption of these changes was minor. Both the initial amendments and the consequent changes were introduced as presidential legislative initiatives, with the constitutional working group having no status within the parliamentary procedures. There was not much of a discussion during the consideration phase, and not many changes were introduced within the parliament.

Reacting to the Threatening Coronavirus

On March 15, at the same time that the pandemic began to be officially recognized by the Russian government, a special working group under the State Council was created to react to the pandemic. There followed a wave of counter-pandemic bills introduced mostly by the government and less often by the deputies themselves.

These fall into two main categories. The first: governmental bills that were necessary to ensure economic support and monetary distribution to counter the pandemic’s effects. The second: the legalization of lockdown. According to the Russian political tradition of downplaying the role of parliament, the first set of bills was introduced by the government while the potentially unpopular, repressive measures came from parliament deputies and members of the Federation Council. This restrictive legislation made possible the administration of fines for breaking the so-called “mode of high alert.” A regime of higher security was added alongside the lockdown and required additional legislative fine-tuning to make prohibitions and restrictions legal while shifting some responsibility to regional authorities and adding newly invented “quarantine fines” into regional codes of administrative offenses (on this, as with many other anti-pandemic measures, the example was set by the Moscow government).

Among this lump of legislation, some were rational, necessary legislative measures. Usually, autocratic regimes (or so-called informational autocracies) deal with threats of their own invention, which they are incredibly successful in combating. But when the pandemic struck, it was recognized as a challenge that had to be addressed in a lucid way. Given the general low-key efficiency of the Russian bureaucracy, credit is due that no administrative or healthcare collapse happened during the heights of the ongoing pandemic. Officials met the threat with the help of some tweaking of statistics, especially blatant by regional governments, and with the massive and largely ineffective use of propaganda, but also with some genuine measures such as quarantine restrictions, tax breaks, and monetary aid.

Embracing the Exceptional: Changing Electoral Rules on the Go

All the while, last year, the parliament saw through the unprecedented move to conserve Russia’s current political model, with its re-set presidential terms, substantial rewriting of the constitution, and electoral legislation amendments that significantly distort one of the last remaining feedback channels between society and the government, between the electorate and the elected.

Additional legislative initiatives adopted during the spring session of 2020 that had no connection with COVID-19, lockdown measures, or assistance for those suffering, came from lobbying groups that used the extraordinary situation to further their interests and facilitate the legislative process in their favor.

These bills can be divided into two parts. First were those introduced by groups of deputies from the parliamentary majority, the United Russia fraction, and their colleagues from the Federation Council.

The constitutional voting of 2020 proceeded according to newly invented rules—ad hoc practices that were not previously included in Russia’s electoral legislation and laws governing the conduct of referendums. These were introduced together with the constitutional amendments themselves.

Last May, the parliament, without attracting much public attention and making use of the second-reading amendment stratagem, introduced the same changes into the regular electoral legislation for the regional elections of governors, regional legislative assemblies, and federal parliamentary elections. These measures included further restrictions against independent candidates, such as stricter rules about collecting the signatures that independent, non-party candidates need to be registered.

Additionally, the May changes included limitations on candidate rights by enlarging the list of criminal code articles that bar the convicted from running for or occupying elected positions. Previously this list was much shorter and was mostly about certain types of violent crimes. The new bill also added a series of political misdemeanors, such as breaking the rules when attending a mass rally or public event. This includes the infamous Article 212.1 or “Dadin-Kotov” amendment that limits how many times a citizen can participate in unsanctioned demonstrations before incurring major punishments. It also includes restrictions on all types of extremist and terrorist offenses, including commenting on or sharing information about supposed radical events and public pronouncements.

Furthermore, changes were introduced to enable early voting. A similar norm has existed for years in the Electoral Code of Belarus. In Russia, this played out for the first time during last year’s national constitutional voting, which took place over seven days. According to the new legislation, three days of balloting are available during all elections, both regional (with specifics decided by regional legislatures) and federal. However, the process means that ballots are kept for days and nights unsupervised or are sometimes under the supervision of the heads of electoral commissions, the parties most interested in ensuring “necessary” electoral results.

This reform attracted some public attention, but in the absence of journalists on the ground, it was both too little and too late. It can generally be challenging to comprehend the contents of a bill without a certain level of expertise; for instance, they contain vague headers like “Amendments Introducing Changes to Certain Laws of the Russian Federation.” And the mode of introducing the main change as an amendment during the second reading further ensures the virtual invisibility of the law-making process.

Lobbying Under Cover: No Time for Environmental Restrictions

One category of bills that were passed clearly and evidently in the interests of developers and construction lobbyists included amendments in Russia’s environmental/ecological legislation.

When everyone was quarantined and media attention was elsewhere, measures were introduced that allow, for example, easier access for contractors to municipal lands, simplified procedures for demolishing buildings in cities, and fewer restrictions and shorter terms for environmental assessments prior to the building of waste incineration plants. There is a governmentally supported program for building a number of these plants in Russia. Whenever this happens, it creates an environment for protests among residents: people generally do not like the idea of a waste incineration plant being built in their backyard.

The Russian community of developers and builders is an extremely influential interest group, well represented in Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin’s government and playing a major role in the regional administrations of Moscow city, Moscow oblast, and the Republic of Tatarstan.

Public Danger and Popular Trust in a Centralized Autocracy

Parliaments in non-democracies have their own agendas and interests to pursue. The difference between these parliaments and democratic representative assemblies is the lack of connection with voters that could limit the activities of lobbying groups and interest groups. In this respect, COVID-19 brought nothing new; Russia has seen a decline in the trust ratings of federal political authorities since the spring of 2018, a trend that has continued during the pandemic (nor has it accelerated to any great extent).

Almost every country experienced a “rallying around the flag” effect with the pandemic’s onset, even if for a short time, but Russia did not. There was no upsurge in the president’s trust or approval ratings. There was, however, a certain rise of approval toward the government in general and regional authorities, especially visible during spring and early summer.

The process of deteriorating trust, or of eroding societal loyalty, is an objectively determined process that cannot be significantly influenced by external events, even those of such magnitude as the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, whatever people see, they tend to interpret in the same way as previous events, like the pension age reform of 2018. If they were prone to distrust or be disappointed by the central government, they would likely be disappointed by the anti-COVID measures. If they still retain their loyalty to the status quo, they’ll probably be more or less satisfied with the government’s actions.

Ekaterina Schulmann is Associate Professor at the Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences (MSSES), Associate Fellow with the Russia and Eurasia Programme at Chatham House, and Senior Lecturer at the School of Public Policy of the Russian Presidential Academy (RANEPA).

[1] Ella Pamphilova, chair of the Central Electoral Commission, mentioned this in a comment on March 6th. On March 10, Putin made an unannounced visit to the parliament to approve of the third or “Tereshkova amendment,” which appeared suddenly on the same day.

[2] Putin said: “I can tell you from my own experience that in about two years, instead of the regular rhythmic work on many levels of government, you’d have eyes shifting around hunting for possible successors. It’s necessary to work, not look for successors.”

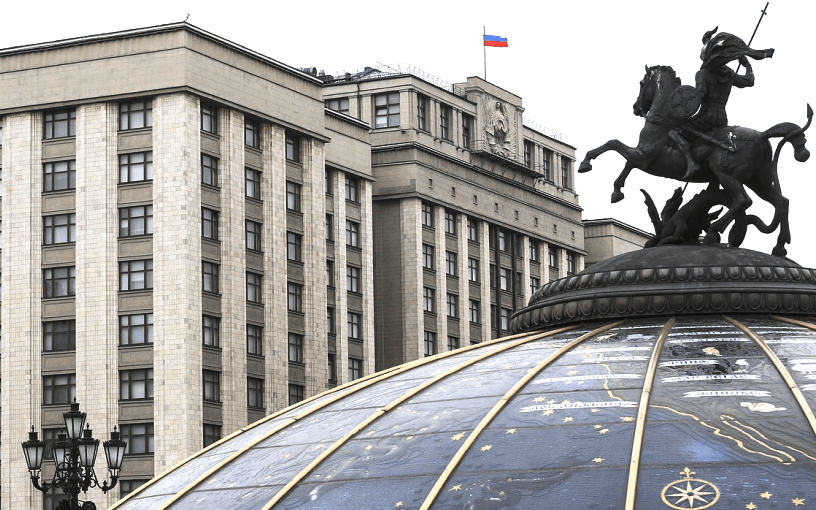

Homepage image credit.