The flow of Russian citizens into Georgia has triggered mixed reactions and controversy. With more than 100,000 new Russians now in Georgia, new demographics and concerns are being created. Fears grew in recent months after the declaration of a partial Russian military mobilization led to a significant increase in the influx. Evaluated here are the implications of this movement from all standpoints, including the associated opportunities this has presented the Georgian government and the potential hazards the country faces. Georgia’s ruling party has attempted to cast the mass immigration as a chance to improve social and economic conditions, but a substantial segment of the Georgian population sees it as posing a risk. The fear is that the influx will have both short- and long-term negative political, economic, cultural, and security impacts. While some anticipate an economic boom, others envisage more crime, corruption, and increased Russian soft power over time.

Statistics and Economics

Not since the late Soviet period has Georgia seen an influx of Russian citizens of this scale—adding to estrangement between Georgians and Russians. Nevertheless, the government of Georgia has tried to portray the arrival of Russian citizens as a positive development. Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili attributed double-digit economic growth to it, which was also confirmed by the Asian Development Fund. Some consider the influx an opportunity that will increase prospects for new infrastructure, services, and jobs, and reduce the emigration of Georgian citizens from the country. However, others believe that these benefits will be limited to immediate, one-off, short-term economic effects. Furthermore, some experts fear that the record-high growth of remittances from Russia (mostly bringing their own money) may further increase Georgia’s unhealthy economic dependence on Russia. They assume that these remittances will decrease in the future, threatening the country’s economic resilience in the long run.

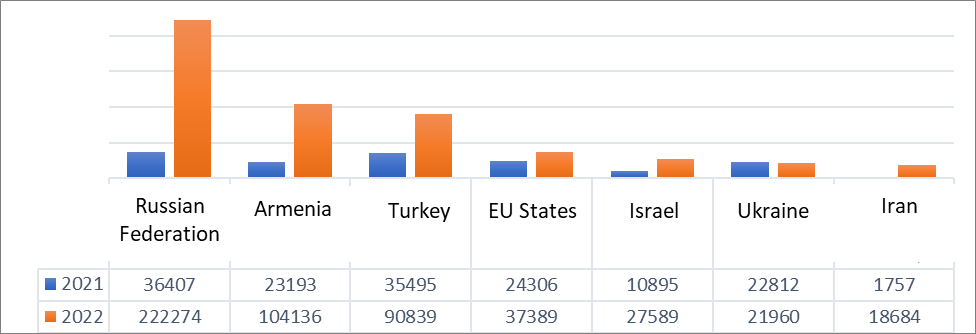

Georgia is a “safe haven” for Russian citizens because they have the right to stay visa-free for one year. In some of the latest numbers, according to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Georgia faced the hugest flow of migrants in September alone, when over 222,000 Russians entered Georgia (see Figure 1). Even if some of those transited to other countries, the settlement of large numbers of Russian citizens in the country has prompted demographic fears, affecting economic and social structures.

Figure 1: People and Transport Entering the State of Georgia

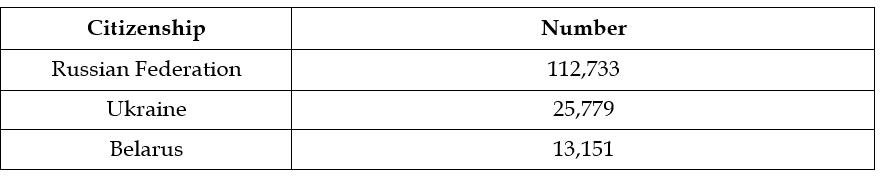

Despite the government’s laissez-faire attitude, the mass influx of Russian citizens could have a negative impact on Georgia’s demographics, creating imbalances, considering that the population in Georgia comprises a mere 3.5 million as opposed to 144.1 million in Russia. Nevertheless, the leader of the ruling party dismissed the idea that “Russians have overcrowded Georgia.” One of his statements declared that the border was being crossed mainly by ethnic Georgians who had been living in Russia, but this is not supported by governmental statistics (see Figure 2). It also ignores long-term settlement difficulties.

Figure 2. Number of Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian Citizens in Georgia

To some, such as European Parliament Member Viola von Cramon, Georgia experiences GDP growth and national currency stabilization as a “benefit it gets from the [Ukraine] war.” Geostat estimates the year-on-year real GDP growth rate to be about 10 percent in 2022, which is far better than expected. Former French Ambassador to Georgia Diego Colas noted that although it was important for a poor country like Georgia not to become poorer as a result of the Russia-Ukraine war, and to maintain stability, reaping benefits from the situation was a different thing. It was this very issue that Western partners alluded to in the spring when they criticized the Georgian government for not joining the sanctions and expressed fears that the country could become a black hole for Russian business.

Due to economic hardship in Georgia generally, citizens have been leaving the country in large numbers. An EU report shows that during the first four months of 2022, as many as 8,097 Georgian citizens sought asylum in EU member states, up 183 percent from the previous year. If the influx of Russian citizens continues at the current rate, these processes may contribute to demographic imbalance. Additional statistics further strengthen these fears. According to Geostat, 9,144 companies were registered by Russian citizens in Georgia in March, up by 72 percent compared to the previous year. Additionally, 6,419 companies were registered by Russian citizens in April, May, and June. An increase has also been observed in the number of residence permits issued as a result of marriages, as Russian citizens may obtain resident permits by marrying Georgian citizens. If Russians decide to obtain Georgian citizenship, they will be able to vote in elections, which could potentially increase the number of pro-Russian voters in the electorate. This can pose social and national security challenges.

The experience of the 2008 Russia-Georgia war, the long, fraught history between the two countries, and the fear of economic dependence on Russia all contribute to the fact that many Georgians do not see the migration of Russians into Georgia as acceptable. The overall economic growth that has taken place since the influx of Russian citizens has not benefited everyone equally and can further deepen inequality between social strata.

The Social Dimension

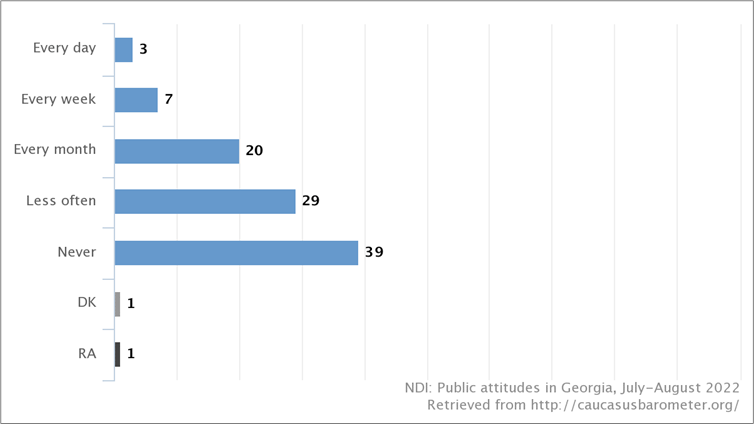

While rising prices of goods and services have brought higher profits to some, they have also harmed economically disadvantaged social groups and decreased their ability to pay for various services and necessary items. Examples include the rise in prices for food products, electricity, and fuel, as well as rent for commercial spaces and apartments. It has harmed socially vulnerable groups in particular. Unemployed people and students from the regions who study in Tbilisi have become increasingly unable to meet their basic needs. Deterioration of social conditions is also seen in the results of public opinion polls conducted in the spring, according to which one in three people has not had enough money to buy food in the past 12 months (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Do You Have Enough Money To Buy Food? (July-August 2022)

There are risks that citizens of Russia who obtain residence permits and try to socially integrate could become competitors with the local population in the labor market. This possibility will become more realistic in Russia’s case of a total military mobilization, which will probably bring a larger influx of Russians into Georgia.

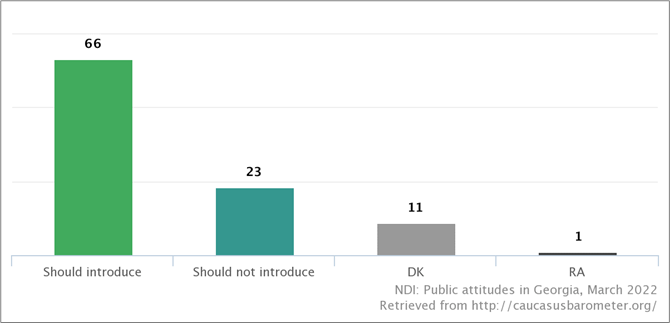

Even before Russia’s half mobilization, public opinion polls released in March suggested that 66 percent of the population of Georgia favors the introduction of a visa regime for Russian citizens (see Figure 4). As such, it is apparent that the government’s vision of the issue diverges from the real attitudes of the population. People are concerned that students and others have been priced out of accommodation by Russian immigrants due to the rising costs of renting (Tbilisi) apartments; capacity has been reached. This has led to an increase in societal dissatisfaction, especially as there have been cases when, for economic reasons, Russian citizens have been given preference over Georgian citizens.

Figure 4. Should a Visa Regime Be Introduced? (%; March 2022)

National Security Risks?

Given that Russia continues to occupy 20 percent of Georgia’s territory in South Ossetia and Abkhazia and is trying to increase its influence in the Black Sea region, a mass influx of Russian citizens represents a potential threat in a number of ways, both short and long-term. Remarkably, due to cultural estrangement and hostile attitudes, the share of ethnic Russians in Georgia had been just 0.5 percent in 2014.

Short-term risks

One immediate risk is the threat of sabotage. EU Commissioner Ylva Johansson cited such reasons for closing the borders of EU member states to Russian citizens and described how Russians are posing as tourists in staged provocations against Ukrainian refugees. This is precisely the kind of potential threat that can be seen in Georgia, too. As there are also sizable numbers of Ukrainians in Georgia, the coexistence of Ukrainian refugees and Russian immigrants in Georgia could result in civic confrontations. More than 160,000 Ukrainians have entered Georgia since the war, with the majority transiting to other countries. The head of the Ukrainian diaspora in Georgia calculated that 25,000 Ukrainians in Georgia are considered refugees as of October.

The risk of groups of saboteurs entering the country also implies a risk of increased vulnerability to Russian espionage activities and an influx of security agents. In at least two recent cases, people who had been living in Georgia confessed to journalists that they had been sent as spies. It is predicted that spies sent on missions by the Federal Security Service of Russia could pose many problems for Georgia by trying to cause internal confrontation, recruit Georgians, and damage the reputation of the country.

Yet another challenge to security is a potential rise in crime. If Russian citizens, having fled to Georgia, exhaust their savings and fail to secure their place in the local labor market, they may resort to other means of survival, including criminal acts. Furthermore, some security experts express concern about a possible rise in corruption. According to them, these people come from a corrupt environment where bribery to get a driving license, residence permit, and passport is an acceptable phenomenon, and it is not likely that they will easily change this attitude.

Long-term risks

The most realistic threats in the long term are those of Russian propaganda, soft power, and territorial security. The concentration of Russians in Georgia would be especially conducive to the effectiveness of Russian propaganda by means of soft power. In this regard, a matter of concern is the rising trend in the Russian acquisition of Georgian real estate. High numbers of Russians are especially conspicuous in Batumi. For example, according to July data from the Public Registry, 585 apartments in 23 residential buildings in Batumi are owned by Russians, and there have been cases where the new residents have demanded that chairpersons of those buildings provide information in Russian. This fact has caused dissatisfaction among local citizens because many see in that demand a threat of Russian becoming a dominant language once again.

The opening of new Russian-language schools in Batumi and Tbilisi could also risk increased Russian soft power. The “illegal” opening of a new Russian school, the School Club Georgia, in Batumi, with lessons in line with the Russian state curriculum, caused great controversy. It was not until the media raised the alarm that the Ministry of Education launched an investigation into the school. In another incident, in Batumi, a Georgian pupil saw the flags of Russia and the so-called Republic of Abkhazia on a school wall and tore them down in protest. The school director reprimanded the pupil, but when the incident became public, the school director was dismissed. All in all, the number of Russian schools in the country sharply decreased after 2011, and the only ones left are attended mainly by ethnic Armenian and Azerbaijani schoolchildren. Despite a rather large Georgian diaspora in Russia, Georgian youth have few ties to Russian culture. The majority are educated either in Georgia or in the West and, consequently, have greater cultural closeness to the West than to Russia. Because of this estrangement and watching Russia’s attack on Ukraine, such an influx of Russians creates a considerable cultural shock for society and especially the younger generation.

Another potential long-term risk is the threat of encouraging Russian aggression. The Batumi incident became especially noteworthy in this regard because of a provocative statement made by the Deputy Chair of the Federation Council Committee on Foreign Affairs, Andrey Klimov, that Adjara may well follow the example of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and “begin the process of secession from Georgia.” In light of the tragic events in Ukraine, Georgian society is especially sensitive to this issue, and it has become a matter of concern for good reason. In this context, the statement by the leader of Georgia’s ruling party that, in the case of physical confrontation with Russians, the government would enforce the law on discrimination on the grounds of ethnic origin drew criticism. Such statements play into the hands of Russia as the Russian propaganda narrative is often based on similar topics. Many citizens fear that in the worst-case scenario, Moscow may apply its oft-repeated method of using supposed “discrimination” against a Russian-speaking population to intervene. In any case, it may use the pretext of defending the rights of Russians in Georgia to attempt to strengthen its political influence.

Conclusion

Public opinion is divided on the issue of the increased migration of Russian citizens to Georgia. The government views this process as a new economic opportunity, while part of Georgian society assesses it through the prism of social and economic inequality and risks to national security. The economic benefits the government highlights may only be short-term, but the country may face increased challenges in the longer term. These social, demographic, cultural, and national security challenges may well outweigh the one-off positive effect on GDP growth (unless well-managed).

As such, it is important for the government of Georgia to take into consideration the criticism it has received from Western partners on Georgia’s policy of seeking to derive economic benefits from the Russia-Ukraine war. Ignoring the recommendations and critical evaluations expressed by Western partners increases the risk that the country will not continue to receive the amount of Western assistance that it has in the past. Furthermore, any decrease in Western assistance would create future risks of increasing Russian influence in Georgia. If this scenario comes to pass, it will not only change the general social and cultural picture but also transform the political situation and endanger Georgia’s current foreign policy course of Euro-Atlantic integration.

Kornely Kakachia is a Professor of Political Science at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University and Director of the Tbilisi Georgian Institute of Politics. Salome Kandelaki is a Junior Policy Analyst at the Georgian Institute of Politics.