Image credit

The Bashkortostan protests in January 2024 were among the largest public actions since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. While protest escalation is notoriously hard to predict, for experts monitoring political processes in the Russian regions, the protest mobilization in Bashkortostan came as no surprise. What was surprising was that the republic’s authorities had clearly underestimated the protest potential of the population and had taken few actions to preempt protest actions.

The immediate spark for mobilization was the verdict and sentencing of Fail Alsynov, one of the most active environmental activists in the republic and a consistent defender of the ethnocultural and economic interests of the Bashkir population. Yet while Alsynov’s sentencing kicked off this protest action, the causes of protest are rooted in three longer-term political developments. First, the Kremlin’s evolving ethnocultural policy has created emotional dissatisfaction (deprivation) among Bashkirs. When linked to regional environmental and governance issues, regional protest becomes more likely. Second, regional elite strategies in the 2010s formed a distinct political opportunity structure marked by opposition alliances with elites who initially provided protection and support. Finally, positive past experiences of protest contributed to the population’s perception of protest as an efficacious and legitimate way of protecting their interests. The combination of these factors not only shaped the recent protests, but also predicts future actions.

The Ethnic Factor: From Loyalty to Protest

Experts often consider Russia’s ethnic republics to be important bastions of Russian authoritarianism. Many republics, including Bashkortostan, have long acted as electoral sultanates that support the president and the United Russia party at significantly higher levels than typical regions.

During the decentralization of power in the 1990s, republican leaders received significant autonomy from the center, allowing them to pursue preferential policies favoring titular ethnic groups. Regional authorities supported the culture and language of the titular ethnic groups and institutionalized ethnicity, creating an ethnic core of voters that supported both the regional and the federal authorities. The basis of this electoral loyalty was the system of ethnocultural preferences and the federal center’s policy of non-interference.

Putin’s 2017 proposal to abolish the compulsory study of non-Russian languages altered this political bargain. The decision affected many members of titular ethnic groups, causing mass discontent in Bashkortostan. It also diminished the loyalty of these non-Russian ethnic groups, whose representatives began to turn away from the party of power and the Russian president electorally. In the 2018 presidential election, Bashkortostan did not contribute to the construction of a national super-majority, instead producing voting results in line with the national average. This change suggests that Putin’s centralization policy undermined the role of the ethnic factor in maintaining control over the population and had long-term negative consequences within ethnic republics.

This negative dynamic also increased popular protest in Bashkortostan. Demonstrations included protests against the construction of a timber-processing plant by the Austrian company Kronospan (2013-2015), rallies against the abolition of compulsory study of the Bashkir language (2017), and environmental protests in defense of Mount Kushtau (2020).

The ethnic factor links local grievances to broader ethnonationalist issues. In the case of Bashkortostan, this has been enhanced by recent region-specific political developments that have transformed the political opportunity structure.

Political Factors: Structures, Leaders, and Opportunities

Protest potential is increased by organizational structures such as horizontal networks, as well as by the emergence of popular protest leaders. These factors arise as byproducts of elite competition. With a monolithic elite, the government can easily co-opt or repress all potential opponents, including the leaders of ethnonational movements. When elites are divided, tacit alliances can emerge that provide incentives for some elite factions to invest in protest activity.

In the 1990s, Bashkortostan’s first President, Murtaza Rakhimov, founded a subnational authoritarian regime similar to those that existed in Tatarstan and the North Caucasus. In 2010, the Kremlin appointed the carpetbagger, or varangian, Rustem Khamitov as Republican President. Khamitov’s lack of connections within the elite and his subsequent circulation of regional officials led to elite fragmentation and the emergence of alternative centers of influence. This within-system opposition sought to destabilize the republic to compromise Khamitov and provoke his resignation. In support of this goal, they invested in grassroots civic activism, including ethnonational Bashkir organizations.

During this period (2014-2018), the public organization Bashkort and its leader, Alsynov, gained mass popularity. This mobilization coincided with the conflict between the regional authorities and the private Bashkir Soda Company (BSC), which aimed to develop Mount Toratau for industrial purposes. Khamitov sided with the public, speaking out against the destruction of shikhans, or preserved reef systems, which many Bashkirs consider sacred. Bashkort headed this environmental protest, which reflected the common interests of the governor and ethnonational forces, with the result that the government had little, if any, concern about the growing organization.

Organizational leaders played an important role in the formation of a wide horizontal network, which created opportunities for protest mobilization. Before Bashkort, the leaders of Bashkir organizations (including the Union of Bashkir Youth and Kuk-Bure) worked in Ufa, the capital of Bashkortostan, ignoring the Bashkir population in rural areas. Their goals were to secure positions of power in major cities and to challenge the dominance of Russians or Tatars. This strategy of nomenklatura struggle did not gain mass support because co-ethnic representation did not provide benefits to the Bashkir majority.

Bashkort’s leaders took a radically different approach to interactions with the population. They centered their work not in Ufa but in rural areas, where they organized cultural and sports events for Bashkir youth and educated the Bashkir population in their own settlements. These efforts increased the popularity of Bashkort and generated grassroots initiatives to establish branches of the movement in cities and villages across the republic. As a result, despite its limited economic resources, the organization quickly blanketed the republic with a horizontal network of supporters, opening more than 30 branches in rural areas densely populated by Bashkirs between 2014 and 2020.

Continued fragmentation among republican elites contributed to the emergence of horizontal structures. Competing elite factions supported grassroots activism. Between 2010 and 2018, Radiy Khabirov also participated in this competition to build support for his bid to become the leader of Bashkortostan. He contributed to protest activity in Bashkortostan, including engaging in behind-the-scenes collaboration (through intermediaries) with some Bashkir ethno-cultural organizations. Following his appointment in 2018, Khabirov ceased to employ this strategy. Yet while many civil organizations submitted to governmental control, Bashkort remained independent.

Khabirov also revised the republican position on the development of shikhans—in particular Mount Kushtau—increasing tensions with Bashkort. In 2018, BSC received permission to develop the mountain and began preparatory work, prompting massive multi-ethnic environmental protests, the core of which were made up of Bashkirs. Bashkort leaders were among the most visible and popular figures of the protest movement. In August 2020, the confrontation between environmental activists and BSC ended in victory for the protesters and increased recognition of Bashkort leaders among their co-ethnics.

The Russian Supreme Court’s designation of Bashkort as an extremist organization in 2020 did not affect the popularity of the organization’s leaders, who remained heroes to the majority of Bashkirs. Nor did it weaken the horizontal connections and communication through social media that bound the organization together. In 2024, these dense social networks, built over many years, enabled the Bashkort leaders to mobilize thousands of supporters, transforming public indignation over Alsynov’s conviction into street protests.

Protest Generates Protest

The third factor shaping protest mobilization is the popular perception of protest, which is rooted in both state actions and past protest experiences. The Mount Kushtau events were an example of successful protest without mass violence. This positive experience may have increased support for protest actions in the republic. To test this proposition, we analyze original survey data collected in spring 2021, less than a year after the Kushtau protests. The data, part of the LegitRuss project, included both a nationally representative sample (N=1,500) and six regional oversamples (N=600), including Bashkortostan, allowing for a comparison of regional protest potential with the national average.[1]

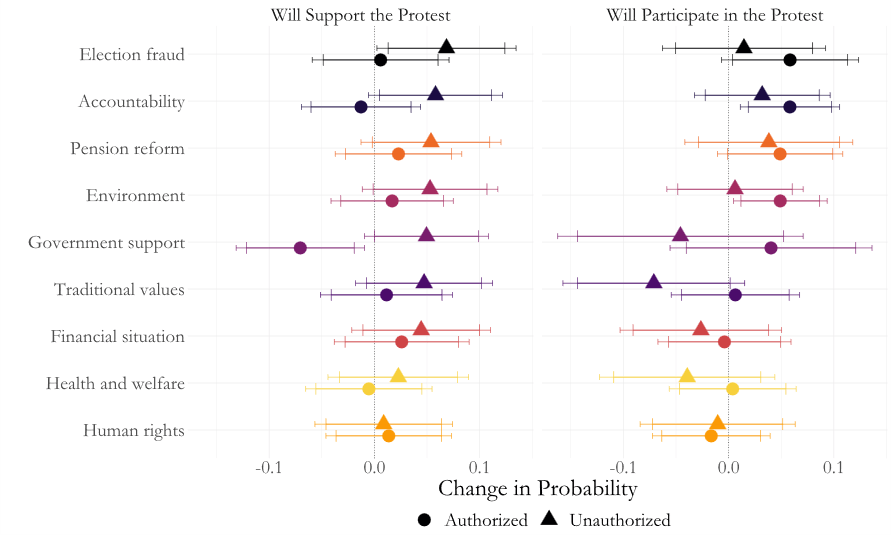

The questions used to capture willingness to protest differentiated between nine different protest causes. Respondents were asked about their support for and willingness to participate in protests related to health and welfare, pensions, environmental protection, the protection of human rights, the protection of traditional values, opposing electoral fraud, demanding government accountability, in support of the government, and against the deterioration of the financial situation. If respondents expressed support for protest on these topics, then they were asked about their willingness to participate in such a protest. Half of respondents were asked about support for and participation in authorized protest, while the other half were asked about unauthorized protest, allowing us to isolate the effect of preventative repression on the decision whether or not to protest.

To gauge the effect of regional factors on support for and willingness to participate in the protest, we ran a series of logistic regression models that, along with region and protest authorization, include several socio-demographic and biographical variables (gender, age, parenthood, education, self-reported interest in politics, TV exposure, employment, dependence on government benefits, and household financial situation and changes thereto in the previous year) as controls. Each model also looked at the interaction between the Region and Authorization variables, as we expected the effect of authorization of the protest to differ across regions. For each of our nine protest causes, we ran a pair of models, one predicting support for the protest and the other the respondent’s willingness to participate in those protests they support. Figure 1 summarizes the results of the analysis for Bashkortostan.

Figure 1. Bashkortostanis’ Willingness to Support and Participate in Various Types of Protest

Source: Compiled by the authors based on 2021 LegitRuss data.

Note: The figure shows Bashkortostanis’ willingness to support and participate in various types of authorized and unauthorized protest compared with the national average. Marginal effects of the region variable were calculated based on logit models, with all other variables taken at base level (for categorical variables) or at their averages, except the Authorization variable, which was taken both at authorized and unauthorized levels to measure marginal effects for these two types of protest separately. Thinner confidence intervals represent 95 percent significance and thicker ones 90 percent significance.

As Figure 1 shows, the level of protest potential in Bashkortostan differed from the national average on five types of grievance. In 2021, Bashkortostani respondents were significantly more supportive of unauthorized protest against election fraud and on issues of government accountability, as well as pro-government rallies. They were also borderline-significantly more supportive of protests on pension reform and environment—two issues that were on the agenda at the end of the 2010s. Importantly, on all but one of these issues, Bashkortostanis differed from the nationally representative sample in supporting unauthorized protest only. This finding implies a general understanding that authorized rallies are not genuine or reflect forcible mobilization by the authorities. This interpretation is strengthened by the significant negative marginal effect for support of authorized pro-government protest.

The success of previous protests is reflected in the support for unauthorized protests. This increases the pool of potential protesters who might be mobilized either through an organization or through the presence of people on the streets. Yet the state’s signal that unauthorized protest is subject to police action increases the cost of protest and dampens respondents’ enthusiasm to participate. In this regard, Bashkortostanis are not distinct from other Russians: they are no more willing to participate in unauthorized protest than their counterparts in the rest of the country. At the same time, they show individual willingness to participate in politicized protest—such as against election fraud, and for accountability and environmental protection—if the protest is authorized. These results demonstrate that potential protesters in Bashkortostan are sensitive to the costs of unauthorized protest, yet—due to past protest experience—Bashkortostanis are more willing to protest than Russian citizens as a whole.

Protest Legacy

Regional authorities responded to the protest in Baymak with significant repression. One protester died after being beaten by police and the number of victims continues to rise. In total, from January 15 to January 31, the regime opened 53 criminal and 163 administrative cases. These actions have significantly increased the costs of future protest participation. They have also damaged movement structures and diminished the popular sense that protest is effective.

It will be more difficult to neutralize the ethnic factor, which has become even more relevant since the January protests. Those events exacerbated the national grievances of many Bashkirs, as evident during Khabirov’s meeting with members of the World Kurultai of Bashkirs immediately after the protests. At this meeting, People’s Artist of the Republic of Bashkortostan Rif Gabitov proposed to honor the memory of Rifat Dautov, who had died following his arrest. The fact that the suggestion infuriated Khabirov revealed a clear disagreement between ordinary citizens and among the regional elite.

This episode also speaks to the evolving role of elites in the opportunity structure. Behind the apparently monolithic political circles of Bashkortostan lie deep differences in elites’ assessments of the ethnopolitical events of recent years. Part of the regional elite has hidden sympathies for the protest leaders and shares their commitment to protecting Bashkirs’ ethnocultural rights. While Moscow’s current control makes open demonstration of these sentiments unlikely, sudden change could come about with the weakening of the federal center.

Conclusion

Events in Bashkortostan show that while it is possible to suppress protests in the short run, their fundamental causes are unlikely to be resolved through repression alone. On the contrary, forceful suppression has increased the ethnic grievances of both the regional elite and ordinary Bashkirs and widened existing elite schisms. In the long run, Bashkortostan will therefore be an even more problematic region for Moscow than it was prior to this protest cycle.

Stanislav Shkel is an independent researcher. Anna A. Dekalchuk is Senior Lecturer in Critical Area Studies, University of Glasgow. Ivan S. Grigoriev is Lecturer in Russian Politics, King’s College London. Regina Smyth is Professor of Political Science, Indiana University.

[1] The LegitRuss survey is a part of the “Values-Based Legitimation in Authoritarian States: Top-down versus Bottom-up Strategies, the Case of Russia” project led by Pål Kolstø and Helge Blakkisrud at the University of Oslo and supported by the Research Council of Norway (project number 300997).

Image credit