(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Cossacks have become a highly recognizable feature of modern Russia, playing a central role in the annexation of Crimea and promotion of secessionism in Donbas. Beyond their role as enforcers and combat irregulars, however, their movement makes few headlines, even while, as argued here, Russian Cossack organizations have become a means of promoting the regime both at home and abroad. As the movement has developed, so has it been commandeered by the Kremlin. This is demonstrated by the role Cossack groups have played in the frozen conflicts on Russia’s borders. Instinctively patriotic and sometimes actively so, Cossacks initially joined in with the fighting to protect those who identified with Russia. Since being appropriated by the Kremlin, however, the “service” Cossack movement, which is still used to project hard power, has increasingly turned to the promotion of soft power in three main ways: institutionalizing a pro-Russian presence outside of internationally recognized borders, appearing as cultural emblems of the country, and maintaining contact with diaspora organizations overseas.

Russian Interpretations of Soft Power

Joseph Nye wrote that “soft power is the ability to get what you want by attracting and persuading others to adopt your goals” and was an important component of the United States’ strategic resources in the Cold War. Nye identified “U.S. Culture and U.S. policies” as sources of American soft power, insisting that mere propaganda was not sufficient to sway international public opinion in, for example, the Global War On Terror. There had to be substance to American claims to lead the world consistent with international law and give “greater sensitivity to the opinions of others in the formulation of policies.”

At first blush, Russia seems to possess a similar concept of soft power (myagkaya sila), using events such as the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics and the 2018 FIFA World Cup to promote positive images of the country to an international audience. However, as President Vladimir Putin wrote in a 2012 article, he understood soft power to be “a matrix of tools and methods to reach foreign policy goals without the use of arms but by exerting information and other levers of influence.” The subtle change from Nye’s articulations of the concept is important. Whereas Nye warned against conceiving soft power as influence-peddling, such an understanding is at the core of Putin’s interpretation of the concept, which he saw as responsible for the color revolutions in Eurasia. It is this understanding of soft power that informs the instrumentalization of Cossack groups throughout the world.

Service vs. Free Cossacks: the Commandeering of a Movement

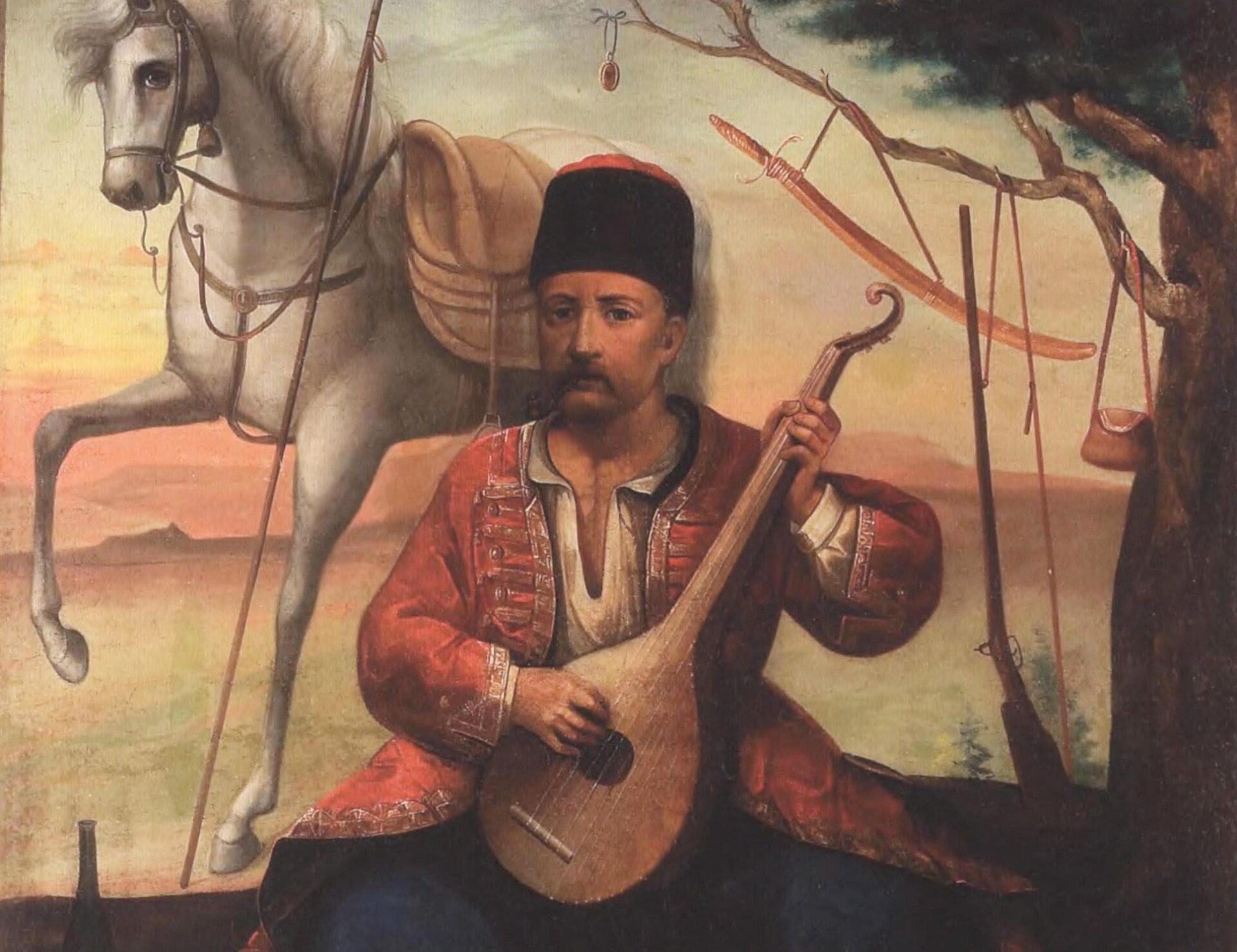

The term “Cossack” refers to a few distinct groups. While there is considerable dispute over the origins of the label, there is a clear division between those who identify as “free” and “service” Cossacks. The “free” Cossacks are those who consider themselves as “ancestrally” Cossack and claim the label from birth. The free Cossacks live mostly in Southern Russia and Ukraine, including the lands around the city of Rostov on the Don. Estimates suggest there are as many as 5 million such Cossacks across Eurasia, which makes them potentially the largest unrecognized “nation” (narod) in that space. The “service” Cossacks originated under Tsarist regimes and saw individuals (irrespective of their ancestral ties to the group) recruited to perform what would today be called paramilitary functions in exchange for privileges such as lower taxes. Cossacks were often used by imperial forces to settle border regions as a kind of force-in-residence.

Today, the state-registered Cossacks are the most salient movement. As of 2016, it comprised 11 “hosts” (vosiko) covering the territory of the country: Don, Kuban, Terek, Volga, Central, Orenburg, Zabaikalsky, Irkutsk, Yenesei, Siberian, and Ussuriyskiy, which were all re-established in the 1990s or early 2000s. Their most recent iteration has seen the creation, in 2018, in the hall of the church of Christ the Savior in Moscow, of the all-Russian Cossack Society (known by its Russian acronym, VsKO) under the leadership of Cossack General Nikolai Doluda. There are 17 tasks of the VsKO, of which the most salient for this memo are numbers 9 (participate in the development of the Cossack Cadets Corpus and a system of Cossack education), 10 (ensure the cultural, spiritual, and moral development of members of the VsKO and youth), and 12 (participate and support the development of international connections with Cossacks abroad in the framework of realizing the state policy of the Russian Federation in relation to foreign collaboration).

The focus on educational and training activities of the VsKO highlights the degree to which the Cossacks are in line with other Kremlin initiatives for propagandizing to youth, including YunArmia and Nashi. Like those other groups, the main direction of education is the promotion of pro-Russian narratives of history, combatting “falsifications” of history, and engaging in activities designed to stimulate interest in patriotism (such as recovering artifacts from World War II-era battlefields). This organization of priorities also plays a major role in preparing Cossack organizations to promote Russian foreign policy objectives.

Cossacks in Secessionist Republics, a Long History

Russian Cossacks today function as soft power resources for Russia’s foreign policy. This was not always the case, and the evolution of their function reflects their institutionalization from initial volunteers-cum-vigilantes to quasi-military GONGO now. Sergey Sukhankin (2019) argues that the Russian state tried to cultivate the image of the Cossacks as volunteers precisely because of the “aura of romanticism.” While not contesting this claim, it remains true that the level of state direction of Cossack activities is greater currently than in the past.

Initially, the role played by Cossacks in the conflicts on Russia’s periphery was mostly as volunteers. In Abkhazia and Transnistria in the early 1990s, Cossack vigilantes organized autonomously to fight for the rights of ethnic Russians. The leader of the Russian Union of Cossacks, for instance, boasted of his members going to fight in both conflicts as well as organizing self-defense squads following the Chechen seizure of Budyonnovsk in 1995. It was estimated that 200 Cossacks were among the mountain peoples who fought for the Abkhaz.[1] In Transnistria, Cossacks from across southern Russia turned up to help fight on the side of pro-Russian separatists. As Cossack lieutenant Fedor Petrovich Parshukov told Komsomol’skaya Pravda at the time, “it was not the government which sent us here… we came here on our own and will leave on our own if the Cossack assembly so decides.” Generally, until 1995 and the introduction of the register, Cossacks were paramilitary volunteers.[2]

In the early days of the uprisings in Ukraine, Kuban Cossacks physically took part in the annexation of Crimea and the secessionist movement in Donbas. There is a direct statement on the VsKO website thanking the “thousand Kuban Cossack volunteers [who] were among the first to go to the aid of our brotherly people and defend our safety.” At that time, the Cossacks performed mostly police and public order functions due to the absence of fighting. In the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, free Cossacks rallied to the side of the liberators who sought to bring them home to Russia. However, as Nikolay Mitrokhin (2021) noted, the Cossacks “were comparatively numerous but lacking in resolve, [they] tended to abandon their positions at the first sign of shelling.” In any case, the free Cossacks of the region soon fell out with the regional authorities who drove them from the territory. Pro-Russian Cossack groups in Ukraine are seemingly also ready to use hard power to destabilize the country if needed. Cossacks remain an instrument of Russian “hard” power but have increasingly played a “soft” power role as well.

The Place of Cossacks in Russia’s Soft Power Toolkit

Currently, Russian service Cossacks promote the country’s soft power in three main ways. First, Russian Cossacks institutionalize a pro-Russian presence outside of the country’s internationally-recognized borders. In Crimea, the Black Sea Cossack Host was re-created in 2018 with an anticipated membership of 10,000 Cossacks to promote public order and run educational institutions that advance pro-Russian narratives of history. They are a part of the All-Russian Cossack Host, which had to be expanded from 11 to 12 hosts to take account of this increased membership. The result will predictably be the cultivation of a pro-Russian constituency through such schools, similar to other neo-Cossack communities.

So too, in the Luhansk People’s Republic, the authorities have created a council of Luhansk Atamans which seeks to unite all Cossack communities and strengthen their cooperation with the secessionist authorities. As with other Cossack communities, the Luhansk group is committed to promoting certain historical narratives and encouraging love of Russia. Organized Cossack groups also promote Russian soft power in Transnistria and Abkhazia, although the South Ossetian authorities denied such a group registration in its statelet on the grounds that it was “not native.” Given the reputation of the South Ossetian authorities for valuing their independence, it is likely they saw the Cossacks’ promotion of soft power as a threat to their authority.

Second, Russian Cossacks have become emblems of the country and a stand-in at international events. Such a move did not happen overnight. In the ceremony passing over the figurative baton of holding the Winter Olympics at Vancouver 2010, for instance, the Cossacks were chosen as cultural representatives for the Caucasus city of Sochi. This was despite the protests of the Circassian diaspora and activists inside of Russia, for whom the Cossack gendarmes of the nineteenth century represent agents of genocide. The Cossacks featured significantly in the Sochi Opening Ceremonies as well (even if they made headlines for assaulting the Pussy Riot punk musicians). Also, at the 2018 FIFA World Cup, local Cossack history in Rostov and Yekaterinburg was marketed to incoming fans, promoting Russia and its ownership of the Cossack legacy.

Even in government policy, the Cossacks have taken on a new role in promoting the country abroad. In 2018, when the president attended the wedding of Austrian Foreign Minister Karin Knaisl’ (who was later given a seat on the board of Rosneft), he took with him the Kubanskii Cossack Choir from Krasnodar at a cost of 1.8 million rubles ($25,000). This is despite the fact that the present Kuban Cossacks are descendants of the relocated Zaporozhian Cossacks, who Ukraine claims as a progenitor. The choir has also toured Japan, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Norway, China, Vietnam, Poland, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Australia. Such visibility for a movement so closely identified with Putin cannot help but promote positive images of the country abroad.

Third, because many Cossacks fled the decossackization in the early twentieth century, there are Cossack emigre communities throughout the world. Bringing them back into the fold has been a central theme of Russian Cossack policy. Since 2003, there have been a series of six “Global Cossack Congresses” that brought together Cossacks from all over the world in the southern city of Novocherkassk, usually to discuss questions of history. The fifth Congress in 2015 saw 300 participants representing over 28 countries, including the United States. There are also other Cossack international conferences, such as that devoted to “securing and developing the spiritual-moral and cultural-historical traditions of Cossacks abroad” in May 2016 in Paris.

Such events individually may be small but represent part of a coordinated strategy to reach out to these communities, which appears to be yielding results. Reports suggest, for instance, that pro-Russian Cossack camps and training sites are occurring in California and Oregon. Likewise, the leader of the Zabaikalsky Cossack society of Australia, Simeon Boikov, has taken part in a series of attention-grabbing events such as hanging a pro-Putin flag from a bridge in front of an anti-Putin demonstration. Closer to the Motherland, too, pro-Russian Cossack organizations in Serbia (who appear at first glance to be relatively numerous) united and represented both a potential fifth column and a way of injecting pro-Russian discourse into European narratives.

Conclusion

This memo has outlined the evolution of the Russian Cossack movement from being an institution of “hard” power that participated in frozen conflicts in the so-called near abroad to also being one of “soft” power that works to influence other societies’ attitudes to Russia. This manifests a particularly Russian understanding of the soft power concept. Cossacks have become an increasingly prominent component of the Kremlin’s domestic toolkit and remain ready to use hard power as vigilantes beyond Russia’s borders, yet scholars and analysts would do well to note the “soft power” purposes with which Cossack groups are being tasked.

Richard Arnold is Associate Professor of Political Science at Muskingum University.

[1] Michael Hetzer, “Georgia: Cossack Warriors Reborn as Mercenaries in Abkhazia War,” Inter-Press Service, July 16, 1993. (LexisNexis)

[2] Olga Rvacheva, “Donskoe Kazachestvo XXI Veka. Konstruirovanie Sotsial’nogo Fenomena [Don Cossacks of the XXI Century. The Construction of a Social Phenomenon],” Vestnik Iuzhnogo Tsentra RAN, 5:3, 2009, pp. 89-95.

PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 728