(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) With media coverage of Russia focusing on government crackdowns against prominent opposition political figures like Alexei Navalny, our discussions of Russians’ political participation during the autocratic presidency of Vladimir Putin have tended to focus on the impact of government restrictions on elections and protest activity. But this analysis has neglected the ways that political participation has actually stabilized the Russian regime in the past decade. An examination of patterns in Russians’ political participation over the past thirty years shows that Russians have tended to prefer elite-enabling forms of political participation over elite-constraining forms of engagement. This preference for elite-enabling participation has helped stabilize the Russian regime by providing officeholders with the opportunity to gather constituent feedback on the government’s performance without the risk of losing power through fair and free elections. More specifically, the participatory process of citizen appeals to government officials has enabled the existing regime to maintain high approval ratings and consolidate its control. Over the past decade, the regime has successfully channeled Russians’ preference for contacting public officials to build a legal and technical apparatus to collect and channel citizen feedback behind the scenes in a way that reduces dissatisfaction and prevents it from being expressed through more competitive and contentious political channels.

Political Participation and Regime Stability

Most analysis of political participation focuses on elections and organized dissent. These types of citizen political engagement are precisely what hold elites accountable in democracies and may facilitate the further democratization of hybrid regimes. In Russia, where both electoral fraud and suppression of the opposition are commonplace, however, focusing on these realms of political participation does not provide the full story. It may appear as though only a relatively small fraction of the Russian population is politically mobilized when we focus on the “systemic opposition” (political parties that maintain a presence in electoral politics) or the “non-systemic opposition” (organized groups without political representation). This approach contributes to two misguided perceptions: 1) that Russian citizens are passively resigned to their political system; and 2) that the Russian regime relies on a combination of citizen passivity and coercion to keep the system in place. While popular resignation and coercion certainly play a role in sustaining Russian autocracy, they do not provide the full picture, which includes a meaningful level of voluntary compliance among Russian citizens.

Political regimes are more stable when they can rely on a citizenry that voluntarily complies with regime commands. While the factors that determine the level of voluntary compliance in any polity are complex, they generally include belief in regime principles, satisfaction with regime performance, and trust that people in power will at least partly deliver on their promises. In both democracies and autocracies, the regime needs a reliable mechanism of citizen feedback and elite accountability in order for voluntary compliance to be widespread. The widespread process of citizen appeals in Russia provides exactly such a mechanism.

As I argue in Constraining Elites in Russia and Indonesia (Cambridge University Press, 2016), forms of citizen political participation can be thought of as either elite-constraining or elite-enabling. Elite-constraining participation can prevent leaders from overstepping constituted authority or undertaking unpopular policy decisions. Examples of elite-constraining participation include campaigning for opposition candidates, building political parties, and contentious political acts. Elite-enabling participation, on the other hand, helps leaders enhance their formal or informal political authority by building loyalty among select constituents who may be willing to tolerate an expansion of elites’ power in return for certain public or club goods. Examples of elite-enabling political participation include supporting incumbent party machines and contacting public officials with citizen appeals or complaints.

While Russian citizens have not embraced elite-constraining forms of participation in broad measure, they frequently engage in elite-enabling behavior, which has served to strengthen Russian political leaders’ informal authority to implement changes without facing pressure from electoral mechanisms of accountability. The type of elite-enabling behavior Russians have embraced most fully is particularized contacting of public officials.

Elite-Enabling Participation in Russia

The practice of citizens making appeals to political elites to redress perceived wrongdoing or public neglect is a longstanding tradition dating back to petitioning the benevolent Tsar during the Muscovite era. It evolved further over the course of the 20th century in the context of a Soviet regime that encouraged its citizens to believe in a paternalistic welfare state. In the 21st century, Russians contact public officials because they view this method as more effective for resolving problems than going through electoral channels.

The findings in Constraining Elites—drawn from an analysis of public opinion data over time and in-depth interviews with a representative sample of Russian citizens—reveal a strong preference for citizen appeals and contacting of political elites over other forms of political participation. My interviews demonstrate that individuals choose how to participate based in part on their perception of what acts are effective and that Russians view contacting as more effective than participating in elections or protests. Moreover, citizens often do not view contacting political officials as “political” participation and instead see it as a private matter.

Data from the Levada Center illustrate Russians’ preference for citizen appeals over other forms of civic engagement. According to a February 2019 poll of the adult population in Russia, 53 percent of respondents were prepared to sign an open letter or petition, and 49 percent were prepared to appeal to the executive branch. This high level of willingness to engage in elite-enabling behavior stands in stark contrast to the only 30 percent of respondents who were willing to participate in the work of civic or political organizations; 24 percent prepared to volunteer for civic or political organizations; 22 percent prepared to participate in street protests; and 10 percent prepared to run for office. These findings were further confirmed in an April 2020 Levada Center poll that asked individuals which civic activities they had participated in over the past 12 months. While only 3 percent of respondents had participated in a protest, march, or strike, and 2 percent had engaged in campaign activity, 13 percent of respondents had made an appeal or complaint to a state office, and another 13 percent had signed a collective appeal or petition. Other than voting in elections, engaging in a citizen appeal or complaint process is the most common form of political participation among Russian citizens, undertaken by more than 10 percent of the population.

The Federal Appeals Process

Over the past 15 years, the Russian government has facilitated direct contact by citizens through the development of a legal and technical infrastructure that allows the Kremlin to both gather information about citizen concerns and to address these concerns through existing governance structures. The foundation of the citizen appeals infrastructure is the 2006 federal law “On the Procedures for Considering Citizens’ Appeals.” The law opens by stating that all citizens have the right to appeal to the state. The law offers a precise definition of a “citizen appeal” that can be used to categorize citizen feedback as a “suggestion,” “statement,” or “complaint.” It further grants applicants the right to receive a written response to their appeal, as well as the right to complain about the resolution of their appeal. Several articles of the law address specific timelines for registering appeals, providing information pertaining to them, and investigating them.

In its totality, the law establishes a framework through which citizens can seek government accountability for actions or inactions. By clearly defining what constitutes an appeal and the process and timeline by which appeals must be handled, the law gives citizens a basis for taking legal action against the state for its own inaction in responding to public concerns. Ultimately, the federal government incentivizes citizen engagement through a quiet, private channel rather than more public, elite-constraining forms of political participation.

Consequently, the citizen appeals mechanism facilitates federal government accountability and oversight on two interrelated levels. At the most general level, the information transmitted through citizen appeals gives the state the opportunity to respond to constituent concerns before they erupt into larger crises that could undermine public confidence in the regime. The regulatory framework established by the 2006 law also allows the Kremlin to monitor how regional and local governments are managing citizen appeals. This monitoring helps the federal government determine when to provide targeted assistance to specific regions and make personnel changes. These tactics blunt the ability of governors and mayors to act independently and develop a following of supporters that could serve as a counterweight to the Kremlin’s power. Additionally, the process of regulating citizen appeals incentivizes a particular type of engagement and eliminates a space for competition over political power by converting the issue into a routine matter of government business. This system has allowed the Kremlin to channel citizen participation away from the elite-constraining activities that challenge the status quo.

In order to manage citizen appeals in a way that maximizes the regime’s power, the Kremlin has developed an infrastructure to track and manage information. A key institution in this infrastructure is the “President of the Russian Federation’s Reception,” a network of physical and virtual locations across Russia’s regions. There is an in-person reception five days per week in Moscow, as well as in-person receptions in each of the eight federal districts and 75 regional capitals across the country. Hours, maps, and telephone numbers for these receptions are all listed on the president’s Reception website. Citizens discuss their concerns at these in-person receptions, with reception staff taking down the information or asking attendees to put their specific concerns for officials in writing. The infrastructure to gather appeals is extended further with “Electronic Reception” terminals in 194 cities that have a population of at least 70,000 and are more than 100 kilometers from the nearest physical reception site. Citizens can visit these locations and submit a written appeal directly through a secure computer network.

In addition to these physical resources, the president’s Reception website includes a system for collecting letters, collective appeals, and reports on corruption, which encourages citizens to engage directly from their homes and bypass visits to local or regional offices. A further layer of scrutiny is provided by a “Mobile Reception,” in which staff from the presidential administration travel to different regions to oversee how appeals are being addressed, creating a visible mechanism of federal oversight of lower levels of governance. The whole system presumes a degree of public confidence that the Russian president, like the tsars of the imperial era, will ensure that state officials are following the will of the people.

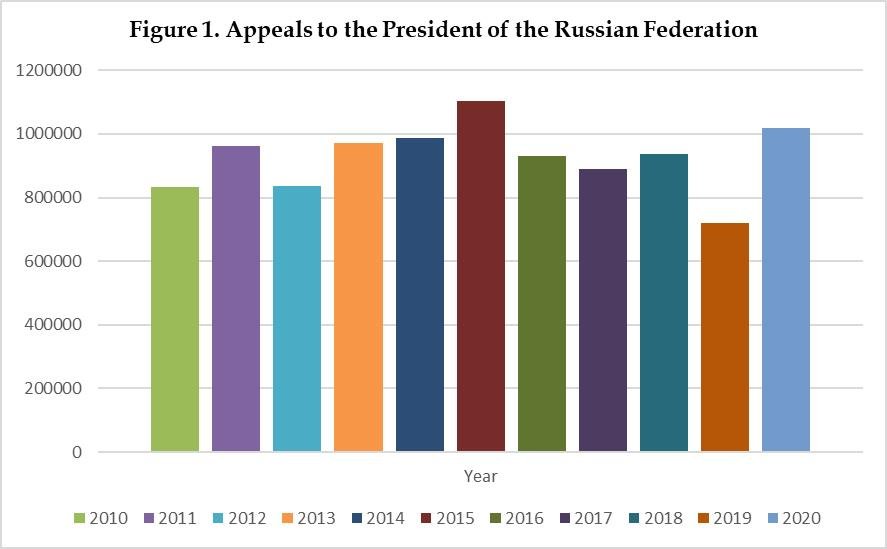

Figure 1 shows the number of appeals received by the Russian president over the past decade. Appeals peaked at 1.1 million in 2015, followed by 1 million in 2020. Even at the lowest point in 2019, the president still received more than 700,000 appeals. Crucially, these data only capture appeals submitted to the president and do not account for those made to other state officials, such as governors, mayors, or representatives of legislative offices. The number of appeals received and the consistent trend in their submission over time demonstrate that this form of elite-enabling participation is a regular form of engagement among Russian citizens.

Conclusion

Political participation can constrain or enable political elites. While we pay considerable attention to the relatively small amount of elite-constraining participation in Russia, such as anti-regime protests or meaningful electoral challengers, we tend to overlook the substantial amount of elite-enabling participation that stabilizes the Putin regime. Russians have demonstrated a consistent preference for contacting public officials as a method of civic engagement that is safe, largely considered apolitical, and often efficacious. Over the past fifteen years, the Russian federal government has developed a system for gathering, reviewing, and addressing citizen appeals. Russians’ preference for appealing to public officials for assistance has enabled Putin to develop the President’s Reception into a mechanism for collecting information about citizen satisfaction, addressing particularistic concerns, and providing oversight of lower levels of government. In modernizing the citizen appeals process for a large percentage of the Russian population that does not view itself as particularly political, Putin has succeeded in presenting himself as an efficient manager and benevolent protector of citizens’ rights.

Image credit