The National Anti-corruption Bureau of Ukraine, commonly known as NABU, offers an instructive case on good governance agencies’ challenges in post-Communist Eurasia. The frontline anti-corruption organization in Ukraine was established in 2015. Endorsed by the OECD and the U.S. government and praised by the European Parliament as “the country’s most effective anti-corruption institution,” NABU is the poster-boy for anti-corruption. It investigates top cases like smuggling at the Odessa customs office, embezzling during the liquidation of VAB-bank, and illegal lucrative amber extraction by officials. NABU has a lavish booklet and claims to have saved up to $55 million of taxpayers’ money in 2020 alone. More importantly, it is politically independent, thus investigating and prosecuting people regardless of connections.

Nevertheless, NABU has two significant weaknesses. First, the public generally distrusts it, which has larger political repercussions than mismanaged public relations should. Second, the Zelensky administration is eager to take NABU under control. The constitutional crisis of 2020 might have provided him with a perfect rationale to consummate the deal. With over thirty proposed amendments to NABU in the legislature, its independence is in jeopardy.

The Anti-corruption Underpinnings of the 2020 Crisis

In mid-2020, two consecutive rulings by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine set on high alert those who care about the anti-corruption agenda in Ukraine. First, the Constitutional Court declared that Artem Sytnyk, head of NABU, had violated the Constitution when he had assumed his position, a move that endangered NABU’s functionality and investigations. Next, the Court incapacitated Ukraine’s asset declaration system maintained by the National Agency on Corruption Prevention (NACP), a central executive body with a mission to run a state register of declarations of civil servants and elected officials. Apprehensive of a ploy to sabotage the anti-corruption institutional framework, activists launched a public campaign to preserve NABU and NACP. Western partners also deplored the Constitutional Court verdicts. The IMF declared the continuation of anti-corruption to be a prerequisite for further cooperation with Ukraine. The EU threatened to cancel the visa-free travel agreement with Ukraine and the U.S. Secretary of State emphasized the necessity to continue fighting corruption in Ukraine.

Eventually, the crisis subsided. The parliament reacted to the Constitutional Court statements regarding some provisions (of Law No. 1074-IX and Law No. 1079-ІХ) that regulate the NACP. With freshly adopted amendments, the agency is fully operational. For the time being. Sytnyk continued serving as head of NABU because some provisions in the Law on the NABU, tackled by the Constitutional Court, have been abrogated. The key anti-corruption institutions, thus, remained in place. For the time being.

The crisis around anti-corruption agencies in Ukraine strikes deep roots. Ire at the Constitutional Court was misplaced, for its rulings were hardly proactive. Instead, a group of MPs solicited the Court’s opinion on the constitutionality of each agency. Its verdicts constituted a part of a coordinated campaign waged by political elites dissatisfied with post-Euromaidan developments in Ukraine. They managed to convince some judges to weaponize judicial powers to challenge efforts to promote anti-corruption in Ukraine.

The understanding that a viable solution requires restructuring the judiciary system lies at the heart of Western partners’ recommendations on how to resolve the crisis. G7 ambassadors suggested a roadmap that condemns attempts to sabotage the anti-corruption architecture and urges to reform the High Council of Justice. European Commission Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis called for comprehensive reforms within the judiciary. The European Parliament published a resolution explicitly deploring “attempts to attack and undermine anti-corruption institutions by members of the Verkhovna Rada [Parliament].” The recovery recipe is clear: to sustain anti-corruption agencies’ political autonomy necessary to track corruption and expand reforms.

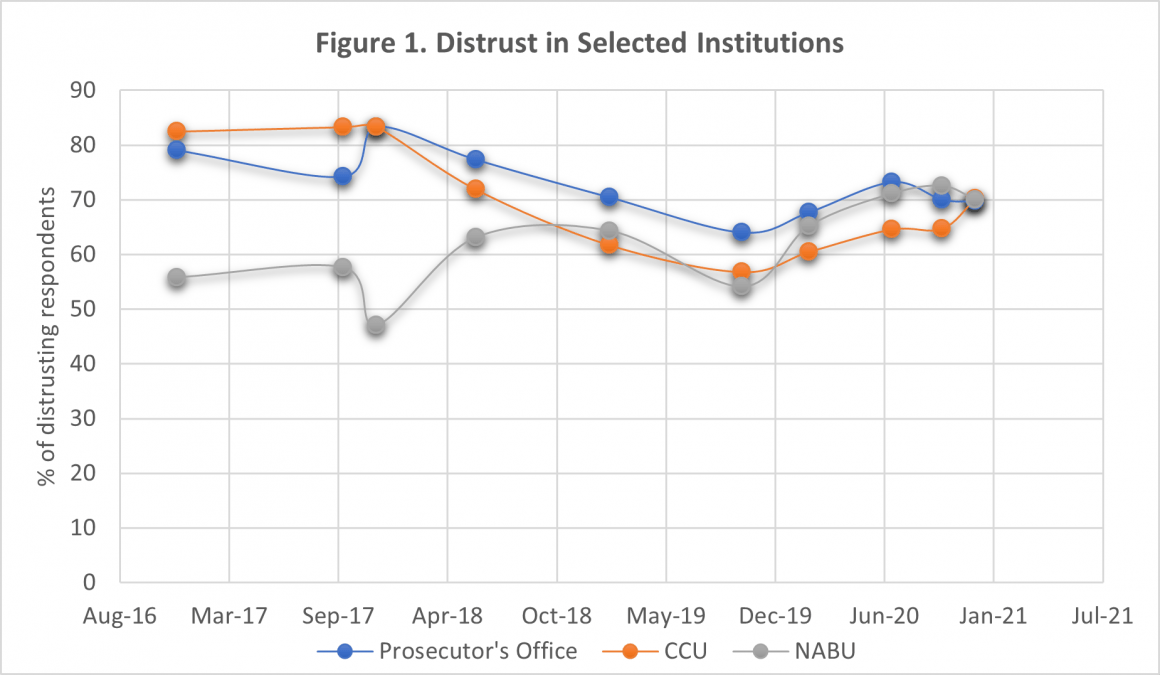

In NABU, We Distrust

However, this strategy might be doomed due to a fatal combination of public distrust and relentless efforts by politicians to subvert NABU’s mission. To illustrate the first issue, I plotted rates of distrust and trust in NABU between Winter 2016 and Winter 2020.[1] For comparison, the figures are complemented with scores for the Constitutional Court and the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Throughout its existence, between 50 and 70 percent of Ukrainians distrust NABU. Furthermore, there is a visible negative trend. The dismal score is comparable with that of the Constitutional Court, with both leveling during the constitutional crisis of 2020 (see Figure 1).

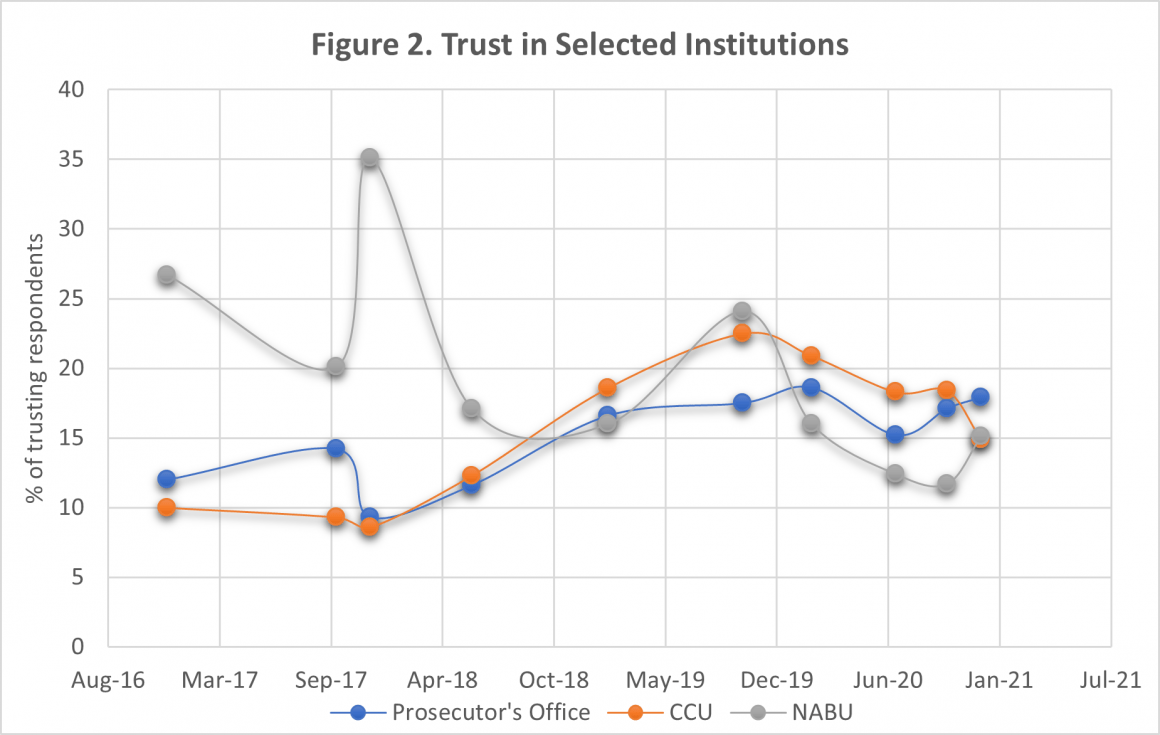

Figure 2 offers a glimpse of regularities. The ups and downs of trust correspond with four stages of NABU’s history that will be outlined below and relate to notable public relation shifts and their political repercussions.

The Four Stages of NABU History

1. Gaining momentum (April 2015-December 2017)

Since NABU’s inception, there have been mixed opinions about its structure. An independent commission elected its head, who could not be easily dismissed, to a seven-year tenure that exceeded a typical electoral cycle, thus making NABU relatively autonomous. Operationally, NABU’s agents were trained by the FBI and subsidized by Western partners. Still, many harbored doubts over whether the agency would make any difference. After all, its mission is to investigate corruption. Judicial prosecution is conducted by another body, the Special Anti-corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO), which is accountable to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the head of which is appointed by the president. Initially, the heads of NABU and SAPO managed to establish cooperative relations. A string of revealing investigations followed, including probing into embezzlement at the National Nuclear Energy Generating Company of Ukraine and fraud at the largest gas producer, UkrGasVydobuvannya. As a result, trust in NABU accrued.

Simultaneously, NABU organized a public relations campaign to present the agency as open, unbiased, and goal oriented. Sytnyk regularly appeared at press conferences. NABU’s official webpage was informational and user-friendly. NABU also cultivated ties with civil society circles. Some, like Vitaliy Shabunin from the Anticorruption Action Centre, converted into staunch allies within the activist community. Improving public relations seemed to be beneficial to NABU’s mission. However, later, it would be given a different spin that would haunt NABU.

2. Anti-corruption infighting (December 2017-April 2019)

Given NABU’s mission to fight (top-level) corruption, its actions were bound to irritate influential politicians. NABU could not help being entangled in politics either as a tool or as a target. Operational autonomy made the second more likely. In October 2017,NABU investigated an embezzlement case implicating Oleksandr Avakov, a son of Minister of Interior Arsen Avakov, himself closely associated with former President Petro Poroshenko. In November 2017, the NACP suddenly charged Sytnyk of being in non-compliance with the country’s electronic declaration policy, a “cornerstone” of the anti-corruption reform. Things promptly got ugly. Several days later, a whistle-blowing official from NACP accused the head of the NACP, Natalia Korchak, of falsifying the electronic declarations check procedure. NABU launched an investigation. In return, the Public Prosecutor’s Office initiated an inquiry against Sytnyk. Within the melee, SAPO’s head Nazar Kholodnytsky voiced his concerns with the NABU-NACP conflict and blamed Sytnyk for deterioration.

A rupture between Kholodnytsky and Sytnyk, never to be fully closed, proved detrimental to anti-corruption efforts. Cases built by NABU led to no indictments. One can debate whether this was due to unconvincing evidence or lack of zeal applied by SAPO. Still, one way or another, the meager outcome of much-publicized activities sapped public confidence in NABU. Unpleasant infights with NACP and SAPO, often manipulated by politically motivated Public Prosecutor Yuri Lutsenko, accelerated the evaporation of trust. (At one point, NABU even bugged Kholodnytsky’s office to prove he was intentionally “killing” cases.)

To make matters worse, a new adversary emerged. In October 2017, the Kyiv District Administrative Court, which for a long time has been honing its political connections with biased verdicts, accepted charges by parliamentarian Boryslav Rozenblat (then under investigation by NABU) and opened a case against Sytnyk for airing information about Paul Manafort’s work for Victor Yanukovych, thus further meddling in the 2016 U.S. elections. The negative coverage contributed to NABU’s plummeting trust rate.

3. Recovering (July 2019-January 2020)

Trust in NABU rebounded when the agency probed the Kyiv District Administrative Court itself. In July 2019, NABU announced it had wired the Court internal communication and possessed evidence that several of its judges were packing the organs of judicial independence with its loyalists in collision with other judiciary officials. Seeing an attempt to capture the judiciary from within, NABU raided the Court’s headquarters looking for further incriminating evidence. Although the High Council of Justice, the only institution authorized to suspend judges, rejected a plea to suspend the head of the Court, NABU’s move against the infamous court ensured renewed attention and sympathy. On a broader scale, NABU managed to improve cooperation with the police, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and even SAPO, building up to 500 cases, making this most successful phase in its entire history.

4. All-front assault (since January 2020)

The move against the Kyiv District Administrative Court—and by extension against corruption within the judiciary—significantly raised the stakes. The broad repercussions of NABU’s actions led a coalition of politicians, judges, and oligarchs to attack NABU from all sides.

Since December 2019, Sytnyk has been listed in the Unified Registry of Corrupt Officials (run by the NACP) for receiving an inappropriate gift—an unpaid weekend at a resort. Whether the misdeed was real, a set-up, or made up is beyond the scope of this memo (Sytnyk claims to have paid for the sojourn but lost the bill receipt). Still, the fact that the head of NABU might be corrupt was too convenient a tool to be missed by opponents. The Constitutional Court decision delivered an even more crippling strike in August 2020. Adding insult to injury, the Kyiv District Administrative Court’s October 2020 verdict ordered that Sytnyk’s name be stricken from the Registry of Officials because he was barred from heading NABU.

Opponents also wage media warfare, citing a lack of trust in NABU as proof the agency is damaged beyond repair. There are signs of a coordinated campaign because spiteful officials, businessmen under investigation, media close to the judiciary, and judges themselves all refer to this fact. Another common feature of the anti-NABU offensive is to represent the agency as subservient to foreign (Western) interests in collusion with NGOs. The head of the Kyiv District Administrative Court mocked “NGO henchmen of the corruptive Head of NABU.” Oligarch Oleg Bakhmatiuk complained about being persecuted by “Sytnyk and his herald Shabunin.” The ex-deputy head of the Public Prosecutor’s Office published a diatribe against NABU and grant-seeking NGOs that act contrary to national interests. This is the point where the cultivation of ties with activists and much-publicized Western support backfires.

Troubles Ahead

There are three issues with NABU’s public relation style that are responsible for its negative public perception and threaten its organizational viability.

First is the lack of tangible results. Here, NABU fell victim to its aggressive promoting style with lofty promises and self-celebrating announcements. This was an attempt to make NABU’s mission more appealing to the public. There is a petition to dismiss Sytnyk because “instead of fighting corruption, NABU promotes itself shamelessly.” Critics point to the fact that none of the high-profile cases have been taken to court. There is a systemic problem since courts stall the processes and wealthy suspects flee due to police laxity. However, in low-profile cases, the situation is not better: even the much-celebrated record-breaking result of 77 verdicts out of 300 cases for 2020 is unimpressive. Hence, a management challenge: to lessen public expectations without downplaying NABU’s mission.

Second, the inability to achieve desirable goals provokes the confrontational style adopted by NABU. Sytnyk is overtly displeased with sloppy prosecutorial performances and judicial listlessness. However, it is hardly constructive to vent frustration on possible allies. Other agencies are irritated by investigation details posted on social media, leaks, recriminations, and reliance on activists. Moreover, NABU detectives themselves commit procedural missteps which, for example, force the European Court of Human Rights to dismiss a case. All in all, regular frictions with the Public Prosecutor’s Office, NAPC, SAPO, Security Services of Ukraine (SBU), police, and/or State Bureau of Investigation are directly responsible for the decline of public trust. Therefore, the organizational challenge is significant: to improve cooperation with other law enforcement agencies even though they are more constrained in their operational choices.

Third, public relation blunders provide adversaries the aims and means to thwart anti-corruption policies, which means discrediting NABU. As shown, they explicitly cite high levels of distrust in it to undermine its activities. Likewise, they accuse NABU of acting against Ukrainian interests. Here, one can detect indices of a grand strategy. As analyzed, one-third of all paid publications in the media has been pressed by the “Opposition Platform–For Life,” an anti-Western political party. Allegations of external governance imposed on Ukraine constitute the third most abused idea within this salvo. NABU, with its Western connections, represents a perfect target for many shots. NABU antagonists, besides, tailor their message to a particular listener. The Kyiv District Administrative Court addressed a note to President Volodymyr Zelensky that “malign actors from abroad seek to establish control over the judiciary.” Meanwhile, the deputy head of the presidential office accused Sytnyk of being a national security threat because he is controlled overseas.

Conclusion

NABU’s detractors may have achieved what they sought. Although in November 2020 Zelensky promised to keep Sytnyk and to sustain NABU’s autonomy, reality reveals other plans. As of February 5, 2021, there were 36 amendment initiatives to the bill on NABU. Most suggest curtailing NABU’s independence. On February 15, the Cabinet produced yet another draft that dismisses Sytnyk and enhances presidential control over the bureau. Minister of Justice Denys Maliuska referenced the Constitutional Court-provoked crisis as a rationale to amend the agency’s status and said that gaps in the law should be closed.

There is, however, a more cynical interpretation. Always a troublemaker, on February 10, 2021, NABU started investigating corruption in COVID-19 vaccine acquisition. The case could implicate the healthcare ministry and its director, who retorted that “such allegations are contrary to Ukrainian patriotism.” In a perfect storm of COVID-19, corruption, and constitutional crisis, the Zelensky administration seems to have found an excuse to achieve a long-desirable goal—to terminate NABU as an independent agency.

Ivan Gomza is Head of the Department of Public Policy and Governance at the Kyiv School of Economics.

[1] The data comes from regularly collected opinion polls by Democratic Initiatives Foundation (December 2016) and Razumkov Center (October 2017, December 2017, June 2018, February 2019, October 2019, February 2020, July 2020, October 2020, and December 2020). The data aggregate answers “rather (dis)trust” and “(dis)trust completely” for a unified score. Since the Constitutional Court was not included in December 2016 and October 2017 questionnaires, the figure reports in its place “(dis)trust in the judiciary” (scores are comparable over the observation period).