Amid Rwanda’s brutal, society-wide slaughter in 1994, U.S. Secretary of State Warren Christopher retorted to a reporter, “If there is any particular magic in calling it a genocide, I have no hesitancy in saying that.” This off-the-cuff remark revealed a serious policymaker oversight in understanding how the presence of genocidal ideology in a given context fundamentally changes the policy options available. Given the severity of violence caused by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine—and the Western and other assistance committed—diagnosing Russia’s violent aims must be one of the key preoccupations for policymakers today. This memo underscores the policy relevance of applying existing comparative genocide studies research to the Russia-Ukraine war.[1] Globally, contexts with credible allegations of genocide are among the world’s most chaotic, politicized environments. Along with massive human suffering and rapidly changing dynamics, new analytic technologies have increased the data points available for analysts, contributing to a form of information overload. In such contexts, empirically-grounded social science frameworks prove invaluable by focusing policymaker attention on the most important dynamics for decision-making.

Accordingly, I first apply these frameworks to Russian perpetrator behavior in Ukraine, contributing a social scientific approach to organizing the mounting evidence of a Russian genocide in Ukraine. Distinctive in pattern and intent, genocides are distinguishable by their destructive purpose waged against all victim population segments. Arguing that the most effective policy responses for halting genocide are built on these variances, I apply comparative genocide research to discuss the: 1) networks of actors carrying out Russia’s genocide, 2) the process of cascading radicalization, 3) the historical precedent that genocides only end in total victories, and 4) the moral and analytic value of labeling Russian violence a genocide.

Analyzing Russia’s Genocide in Ukraine

Inferring Opaque Intentionality

Logistical hurdles notwithstanding, the Kremlin’s August 25th announcement of planned increases to Russia’s armed forces signaled an enduring military commitment to the devastation of Ukraine. Operating in parallel, Russian state messaging continues its dehumanizing characterizations of Ukrainians, while concerns remain high that Russia is preparing another attempt at further offensive campaigns. The overlap of Russian capacity for violence with an expressed appetite for it (i.e., the presence of both motive and means) has been well-documented since the full-scale invasion began. Still, despite enormous suffering, analytic assessments of genocide are not explicitly linked to victim tolls or the scope of the damage. Rather, as I have noted elsewhere, “genocide is a process with specific dynamics that arise from its perpetrators’ intention to extinguish a group.” Pioneering figures like Raphael Lemkin named it the “crime of crimes” as it willfully targets a group’s most basic right to exist.

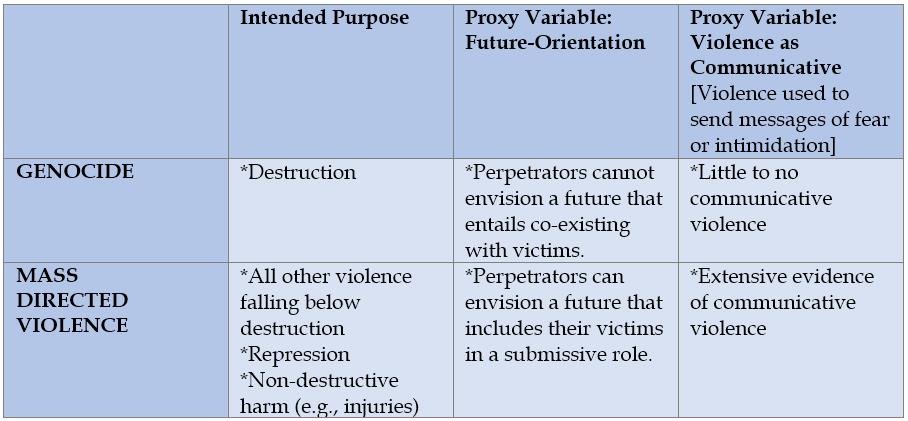

Due to differing perspectives and mandates, the interpretive details—and operational definitions—of genocide have been contested across fields like politics, law, activism, and academia. Experts debate issues linked to its measurement and nature, yet major consensus flags two major questions that indicate genocide in real-time: First, are all segments of the population targeted? Second, is the destruction of the group—not simply severe repression or battering—guiding the purpose and logic of the violence? Drawing from the past thirty years of genocide research, I created corresponding proxy variables that elicit opaque perpetrator motivations and disaggregate categories like “intent” over time and space:

Table 1: Proxy Variables, Intended Purpose of Violence

Ukrainian Holodomor,” Genocide Studies and Prevention, 15 (2), 2021, pp. 10-36.

Table 2: Proxy Variables, Intended Targets of the Violence

Ukrainian Holodomor,” Genocide Studies and Prevention, 15 (2), 2021, pp. 10-36.

Russia’s Destructive—Not Just Repressive—Motivations

The specific narratives promoted in Russia’s non-free media space illuminate influential stakeholders’ internal logic for violence in Ukraine. These statements begin at the top of the governmental hierarchy, with Russian President Vladimir Putin continuing to insist that it is a “historical fact” that Ukrainians are “fundamentally one people” with Russians as late as October 2022. Putin’s statements that the Ukrainian people are intrinsically identical to Russians and separated only by arbitrary circumstances perpetuates the erasure of the Ukrainian national group, a protected category under the United Nations genocide convention. On January 15, 2023, Putin further characterized the military situation in a broadcast interview, stating, “There is a positive dynamic. Everything is developing according to plans. I hope that our fighters will please us more than once again.” These comments came hours after one of Russia’s largest attacks against civilians—a deadly missile attack against a nine-story residency block that killed and wounded scores in Dnipro—as well as after eleven months of documented atrocity crimes by Russian forces in Ukraine.

Such violent sentiments that deny Ukrainian national identity are reiterated by prominent Russian politicians at the local and national levels. Moscow City Duma Deputy Andrey Medvedev called for the “liquidation of Ukrainian statehood in its current form,” stating, “the Ukrainian nation does not exist. It is a political orientation.” Former Russian Federation President Dmitry Medvedev has become increasingly known for his violent bombast, ranging from calling Ukrainians resisting Russian occupation “cockroaches” to suggesting that Ukraine will not exist on maps in two years.

Significantly, influential figures have continued with calls for violence even in the wake of large-scale civilian targeting in Ukraine. After extensive attacks on Ukraine’s civilian infrastructure in October 2022, member of the Russian State Duma Andrey Gurulyov characterized the conditions created by Russian attacks as “impossible to survive. There is no heating, no water, no sewer, and no lights. You can’t cook food, no place to store food, there is no way to transport the food.” After demonstrating his grasp of the toll of Russian attacks on the Ukrainian people, he affirmed them, stating, “All of this is quite effective. I suppose this should be continued. This will produce a very good effect.”

Beyond state actors, this rhetoric is echoed by other media sources, indicating the spread of these sentiments in official and nonofficial messaging. The Russian television channel Tsargrad responded to the August car bombing of Darya Dugina by stating, “We and Ukraine cannot continue to exist on the same planet. It is impossible to coexist with infernal evil,” directly echoing the proxy variables identified above. In each of these statements, this expressed unwillingness to coexist—even with Ukrainians in a subdued role—indicates destructive genocide purposes rather than harshly repressive future conceptions of Ukrainians (i.e., a scenario where Ukraine’s national sovereignty is undermined but not its citizens’ fundamental existence or organically-derived national identity).

While eliminationist language is surprisingly frank in Russia’s case, these proxy variables further clarify if genocidal actions (actus reus) overlap with genocidal motives (mens rea). As other experts and I covered elsewhere, the combination of multiple perpetrator behaviors collectively indicates a pattern of genocidal violence targeting the Ukrainian national group. Some Russian behaviors explicitly correspond to the United Nations Genocide Convention criteria, such as the mass deportation of approximately 1.9 million Ukrainian civilians with Russian confirmation of at least 307,423 Ukrainian children fast-tracked for Russian adoption. Although precise statistics will continue to be verified as the war continues, these figures indicate significant patterns of violence. Applying proxy variables clarifies more subtle details, such as the increased coordination required by full-scale genocide, emphasizing the importance of pre-February Russian bureaucratic planning for filtration camps and judiciary changes designed to legalize trafficked Ukrainian children in Russian homes.

A focus on future orientation also underscores the dual significance of Russian killing with violent, coerced Russification—echoing longstanding Kremlin historical precedent. Through this lens, the internal logic of torturous filtration camps—designed to weed out those deemed by perpetrators to be “irredeemably Ukrainian” from those who can be forcibly Russified—take on more sinister undertones than other repressive forms of internment camps. Similarly, extreme violence against children (who pose little military threat) and rape with stated motivations to disincentivize future births also indicate the intended destruction of Ukraine’s future generations. Finally, coordinated Russian efforts at population control—through pursuing victims and preventing their flight—belie explanations that land or looted goods would satisfy Russia’s ultimate destructive aims.

Effective Policymaker Responses to Russian Genocidal Intent

Targeting Genocide’s Multifaceted Networks

The proxy variables described above not only highlight what is happening but why. This distinction is needed for effective policy responses that tackle the root causes of violence rather than purely treating its symptoms. With genocidal targeting detected in Russia’s violence against the Ukrainian national group, other established findings from the genocide studies field should shape policymaker messaging and decision-making.

One sobering implication is that this cruel, complex social phenomenon requires a veritable village to achieve. History will remember President Vladimir Putin as a notorious war criminal, but he has yet to pull one trigger in Ukraine. Like other genocides, large numbers of “ordinary” Russians participate in raping, torturing, deporting, and killing civilians and soldiers. This reality necessitates that global leaders eschew more comfortable descriptions of Russian violence as “Putin’s war,” as German Chancellor Olaf Scholz did as late as August 10, 2022.

Instead, five key roles must be explicitly addressed by policymakers and analysts alike in formulating appropriate responses to Russia’s criminal genocidal behavior:

- Direct perpetrators—including Russian soldiers and warfighters.

- Organizers—including Russian bureaucrats, occupation authorities, military recruiters—planners and advisors, passport consular officers, children’s services who participate in deportations, etc.

- Authorizers—ranging from the strategic level of Putin and security service elite through commanders authorizing genocidal battlefield directives.

- Enablers—especially Russian religious leaders and dehumanizing state media commentators who routinely call for Ukrainian extermination.

- Bystanders—who may not approve but do not intervene.

Anticipating Cascading Radicalization

This final category—bystanders—is often neglected in current conversations of Russian genocide yet plays a central role in perpetrating cycles of violence. Historically, genocides do not occur when a specific number of killers emerge but rather when key architects like Putin become surrounded by a passive critical mass that grows convinced that violence is required or even just permissible. Studies show that processes of “cascading radicalization”—operating as a form of genocidal social contagion—can entrap millions in one of these five roles. Worldviews shift, psychological construction of the victims as sub-humans occur, and cruelty is rewarded. The perpetrator society routinely blames the victims for their own suffering, as seen in Bosnia denialism and, more recently, with socially accepted Russian disinformation that Ukrainians bomb themselves.

Even more dangerous, signs of moral reorientation in broader Russian society are occurring. Violence against Ukrainians is transforming from unfortunate-but-passively permissive to actively “ethical.” Dmitry Rogozin, the former head of Russia’s space agency, exemplifies this trend, justifying “putting an end” to Ukrainians by calling them “an existential threat to the Russian people, Russian history, Russian language, and Russian civilians…so let’s get this over with. Once and forever. For our grandchildren.” As these harmful transformations occur in Russian society, they create unpredictable, unstable dynamics that even authoritarian architects like Putin can no longer control. The radicalization unleashed in a perpetrator society can entrench and prolong Russian societal dynamics that have been termed “defensive consolidation.”

Understanding End-Game Scenarios

Historical data demonstrate that genocide perpetrators are willing to incur greater inconvenience and pay greater costs in their pursuit of annihilation. Research further indicates that genocides only end in total victory: either perpetrators achieve their destructive aims or the victims successfully fight back, often with outside help. This historical pattern suggests that comments from former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev, who stated that Russia would continue its war even if Ukraine formally renounced NATO aspirations, are not empty posturing.

Unlike other forms of brutal wars, genocide’s specific totalizing aims combined with profound social changes in perpetrator societies support policy stances that no “snap-back” changes between Western governments and Russia are currently possible. Russian ceasefire overtures must be greeted with suspicion. These delays allow perpetrators to consolidate their control and violent intentions to erase the Ukrainian national group through killing and coerced Russification. Some governmental representatives continue to call for a cessation of weapons to Ukraine, most recently German SPD figures who erroneously termed this an alternative modus vivendi with Russia. With Western weapons Ukraine’s only major option to halting an ongoing genocide, policymaker messaging must ring out more loudly that Russia is not ultimately after Ukraine’s land but rather its people.

Embracing Truth in an Age of Disinformation

The stark reality of genocidal end-game scenarios must spark faster supplies of heavy weapons for Ukraine to reclaim control over its population, particularly from large economies whose military aid has lagged behind capacity, including Germany, France, Spain, and Italy. Russia’s genocidal aims also require greater transparency and action from more of the 152 signatories of the UN Convention, which obligates signatories to both prevent and punish genocide. Moreover, the United Nations itself must address this topic more forcefully.

With the UN created in the aftermath of the Nazi Holocaust yet now constrained by Russia’s veto power on the Security Council, this institution has suffered credibility issues linked to Russia’s full-scale invasion. Although UN efforts have seen successes (such as the Black Sea shipping agreement involving the UN, Turkey, Russia, and Ukraine), other notable failures have raised pointed questions about the emerging international order and the UN’s influence. Critics note that two members of the UN Security Council are credibly accused of genocide: Russia (externally against Ukraine) and China (internally against the Uighurs).

Instead of brushing off such questions, the UN can regain moral leadership and political capital by explicitly addressing the Genocide Convention’s applicability to Ukraine and its signatories’ obligations. A more visible genocide response effort must also include more explicit condemning language, an in-country visit by the Special Advisor for Genocide Prevention, revision of erroneously labeled deported Ukrainians in Russia as “refugees,” and long-term institutional presence, including possible UN peacekeepers, in Ukraine.

The reality of genocide also expands the international community’s obligations to Ukraine, including by Middle Eastern and African nations whose reactions have been more muted. Although some countries and scholars have recognized Russia’s actions as genocide, many Western governments and international advocacy organizations also lag behind. With Ukraine long overshadowed by Russian narratives, these actors must participate in regional decolonialization efforts by listening to local voices and locally-informed scholarship. More than simply asserting truth over disinformation, understanding Russia’s genocidal aims, networks, and end-game scenarios will lead to more effective policy analyses, messaging, and responses to this urgent emergency.

[1] While I focus my analysis on this context, this framework could also be applied to other regional contexts (e.g., Nagorno-Karabakh, South Ossetia, and Abkhazia), as well as historical regional analysis including the Chechen Wars.

Kristina Hook is Assistant Professor in the School of Conflict Management, Peacebuilding, and Development at Kennesaw State University.