By Tymofii Brik, Kyiv School of Economics

“Right now, who could you say is more likely to win… than Yulia Tymoshenko?” – Keith Darden, CSIS Panel, 12/3/2018

Many researchers and pundits have tried to predict the most likely winner of the Ukrainian presidential elections. The key words in Keith Darden’s quote above are: “Right now.” On that day indeed, December 3, 2018, Yulia Tymoshenko seemed to be the best answer because the polls said so! Yet, forty-five days later, the situation changed dramatically. Most pundits shifted their attention to Volodymyr Zelenskyi, the new leader in the polls. Polls changed minds, pundits followed.

In the worst-case scenario, pundits are trapped into whatever ad-hoc numbers such tracking polls give them. But a simple barchart or a cross-tabulation says very little about context, leaving researchers with no room for analysis. There are at least three substantial issues with polls: they do not provide causation or context and and they appear to communicate only a handful of ideas borrowed from social science. Although still imperfect, there are some new tools that analysts could explore—in this case pertaining to the Ukraine election scenario—such as those provided by Texty, Fama, and Datatowel.

Tracking Polls Tell Us Very Little About Causation

Ukrainian pundits have suggested at least three (perhaps, not mutually exclusive) explanations as to why Zelenskyi has become so popular among respondents:

(1) people want to see new faces;

(2) people demand someone who is not from the establishment; and

(3) simple demographics (young people support Zelenskyi).

These are intertwined yet quite distinct explanations. For example, if the third explanation is correct, then the chances of Zelenskyi continuing to lead become smaller since young people do not tend to show up at polling stations in large numbers. If the first two explanations are correct, then Zelenskyi could be outrun by competitors who exploit similar campaign messages. Unfortunately, standard election polls are not designed to test alternative hypotheses.

Tracking Polls Tell Us Very Little About Background

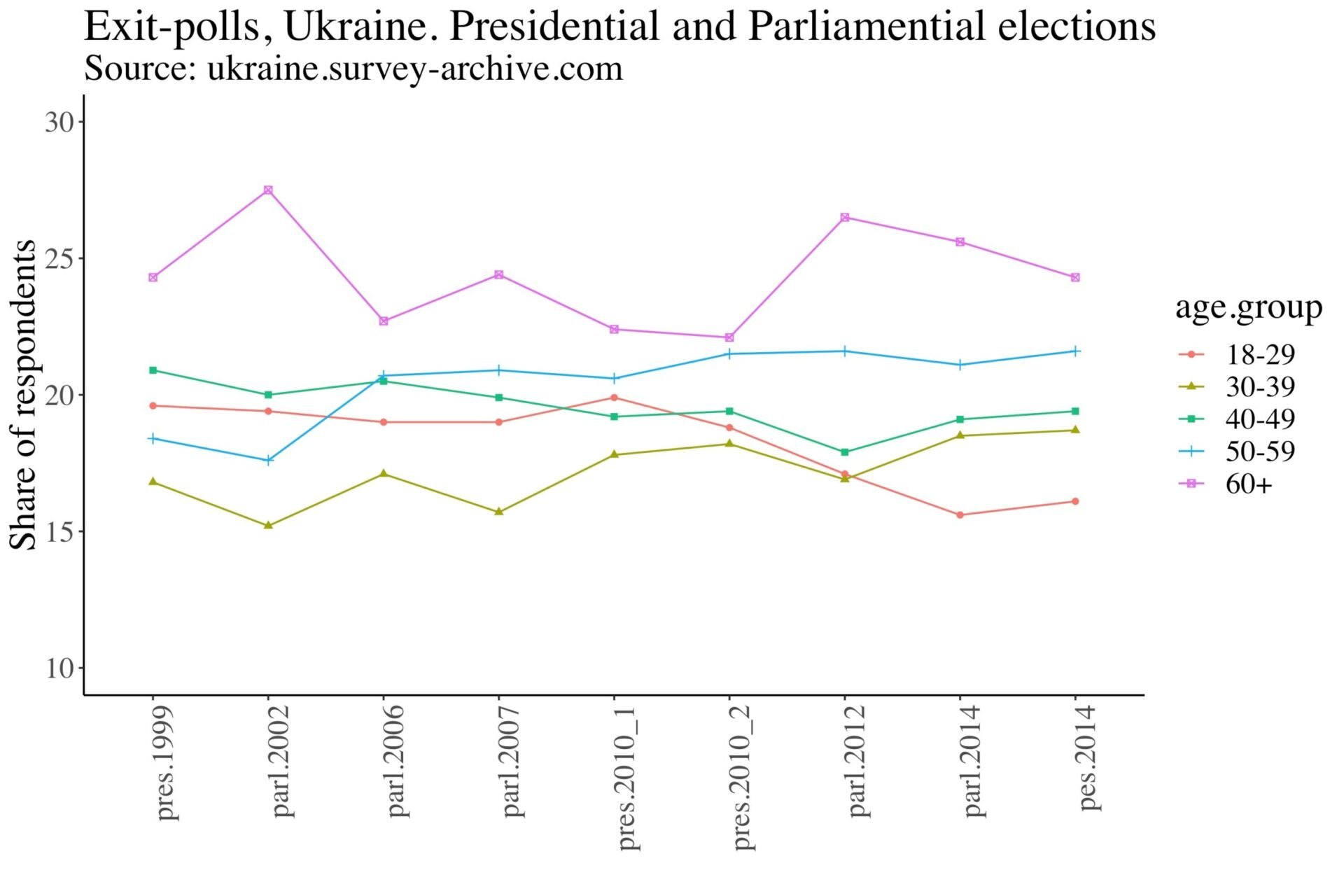

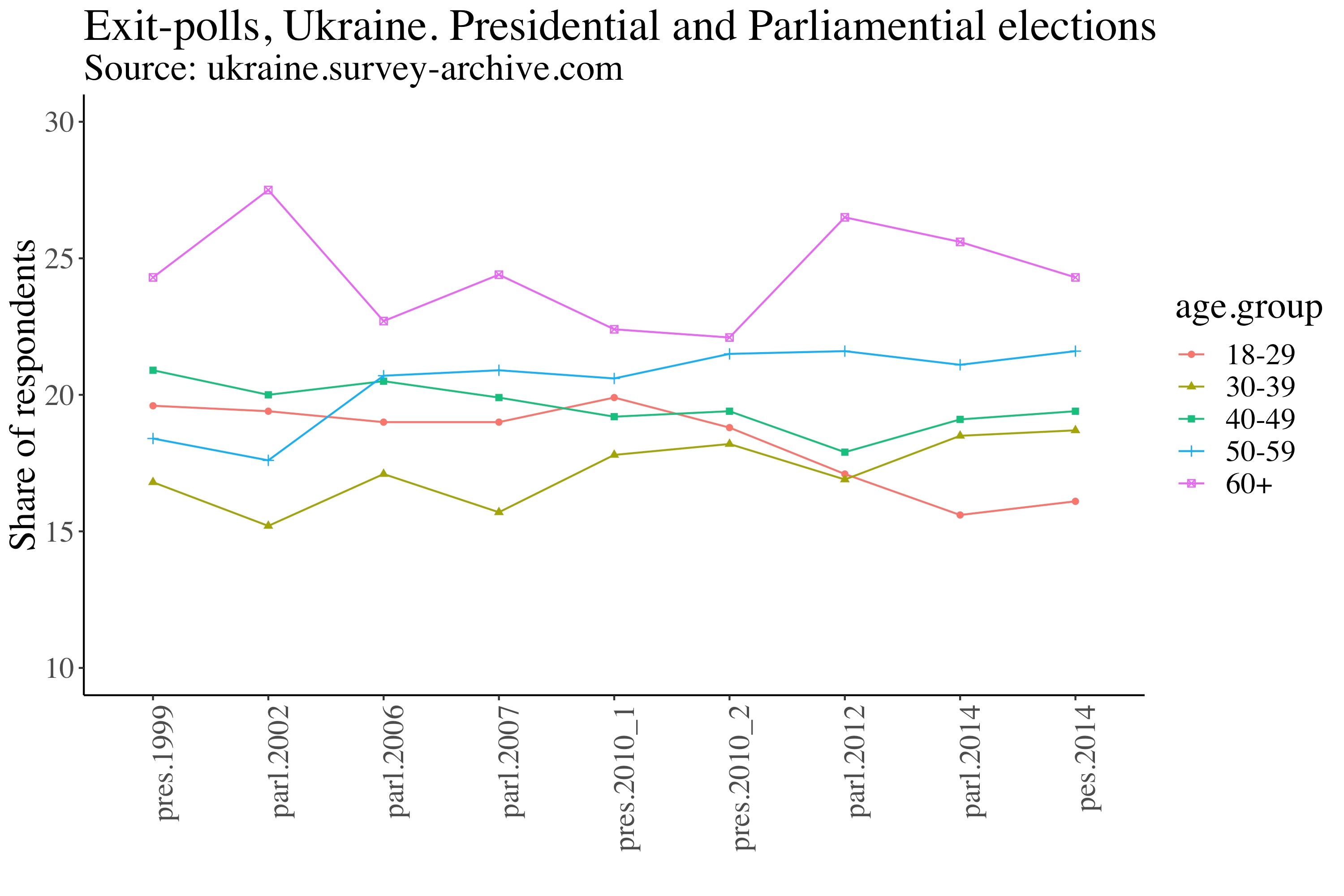

Let us consider, for example, the common wisdom that young Ukrainians tend not to show up to vote. Their answers thus should be weighted by some probability of their actually casting a vote. A simple descriptive analysis reveals more nuances. In fact, exit-poll data show that young people 18-29 were not the least disciplined group and that it has only been since 2012 that young people have seemed to “disappear” from the electoral scene (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Exit-Poll Data for the Ukrainian Presidential and Parliamentary Elections (1999-2014)

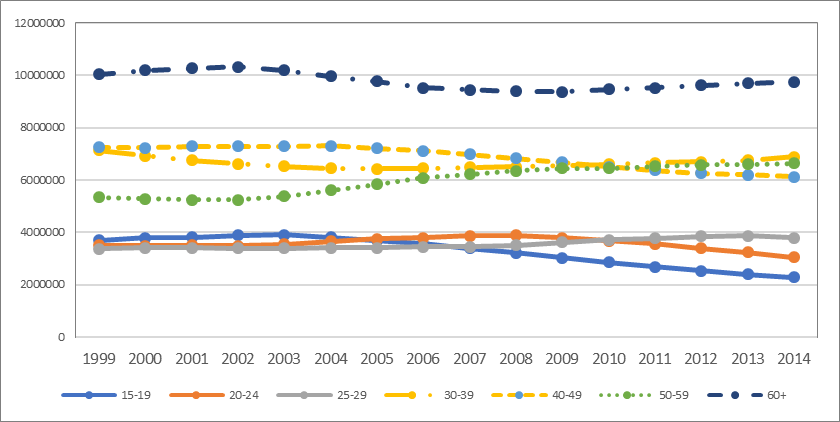

Interestingly, this pattern corresponds to the declining demographic of youth in Ukraine in the respective years (see Figure 2). This information sheds light on contextual factors that prevent young voters from partaking. It is not only about motivation but about demographic shortage. Polls do not supply this background, which leaves researchers with the false impression that they should study individual traits, when in fact they should certainly include contextual factors.

Figure 2. The Decline of Youth in Ukraine (1999-2014) (absolute numbers)

Source: database.ukrcensus.gov.ua

Tracking Polls Are Only a Slice of Social Science

The language of social science is very broad. However, polls speak to only a handful of ideas borrowed from social science, predominantly that expectations of people matter and that attitudes of people correlate with their behavior. In contrast, depending on context, scientists and pundits talk about parties as gatekeepers, about the influence of mass media and political mobilization, the socio-economic background of voters, and about rigged elections and administrative pressures. Clearly, scholars and pundits have ample ability to be creative when analyzing electoral behavior, but for some reason, much wisdom is shattered when we consume polls and barcharts.

To be concise, the main problem, in my view, is that election tracking polls can trap intellectuals into making educated guesses as to what is going to happen even though actual, available information is missing. The analytical payoff of working only from polls is slim. Why do we allow ourselves to fall in these traps? Perhaps because most polls and charts are self-explanatory, user-friendly (simple), and quick to gauge. Indeed, many of us are big fans of saturated models when something complex is explained with a few variables.

Several Useful Solutions

There are alternative, straightforward, and self-explanatory tools that can be used. Below I recommend three organizations for those interested in following Ukraine’s electoral trends in more depth.

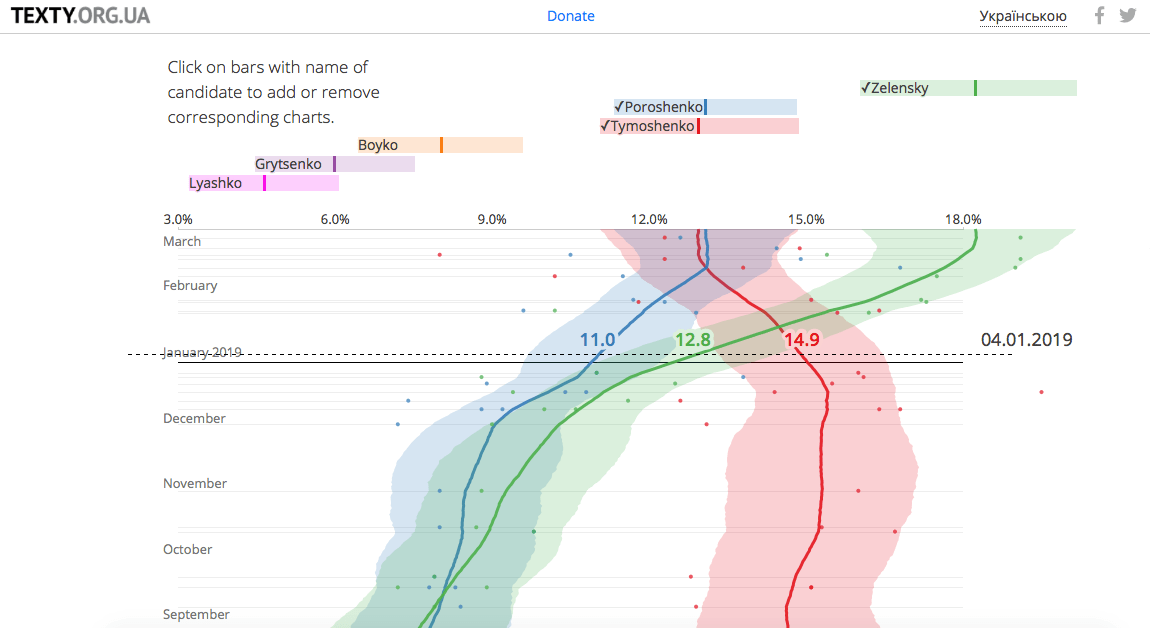

Poll of Polls by texty.org.ua (Russian | English)

This user-friendly presentation shows how public opinion varies across time and polling firms. The reward from these analytical additions are substantial. One can see a process of when and at what cost a certain candidate changed a position. The data can be juxtaposed against any other contextual variable to build a better predictive model. Here is a screenshot:

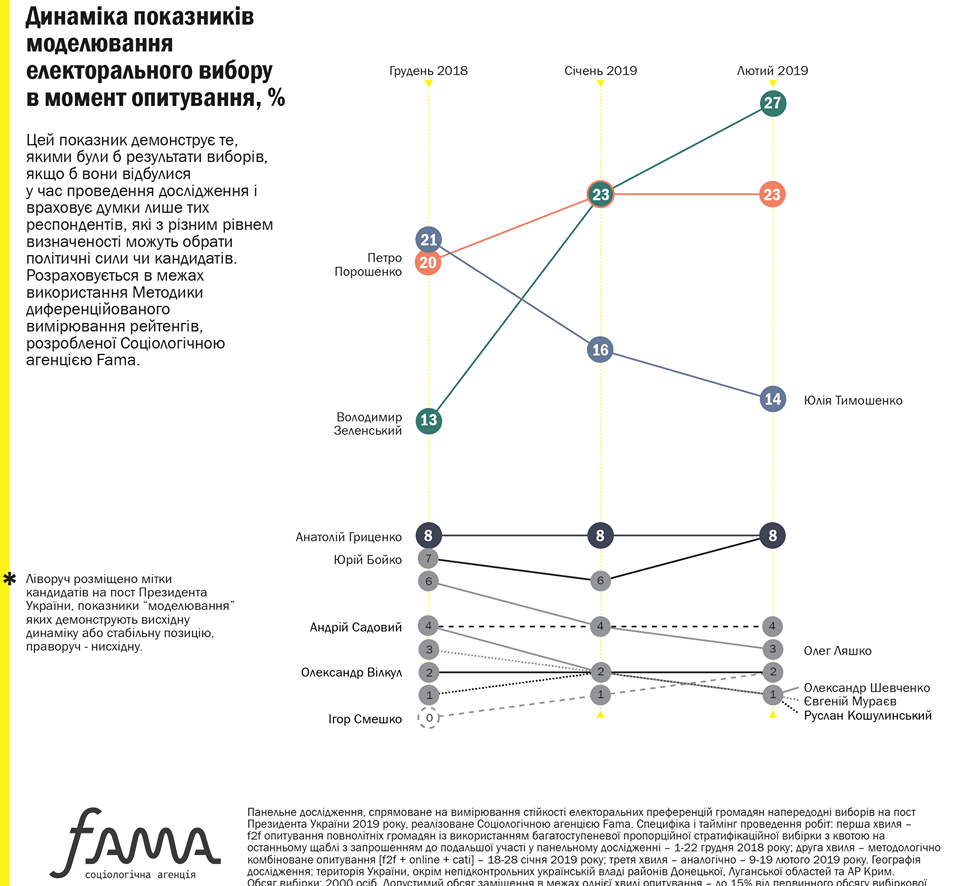

Panel Data by Fama (Facebook)

Pollsters often say that one of the biggest issues for their predictive models is the fact that many respondents have not yet decided for whom to vote. Thus, knowing how “undecideds” change their mind is crucial. Cross-sectional data cannot help here. However, Ukrainian sociologists from Fama have thought about this and come up with a reasonable solution using panel data. Moreover, panel data are crucial for analyzing causality. Here is a screenshot:

Spatial Analysis by datatowel.in.ua (Ukrainian)

Electoral scholars know that attitudes and opinions are more volatile than structural factors that constrain individual electoral behavior. Such constraints were discussed above in the example of demographic decline. One could think about many other structural factors such as rural/urban divisions, media consumption, political competition, and more. Spatial analysis of electoral events can shed new light on how structural factors are working in Ukraine. Here is a screenshot:

I would like to stress that mainstream polls and charts are tools that have their benefits, as with any tool. They cannot be absolutely dismissed. However, they are often based on quite simple assumptions involving individual attitudes correlating with the individual’s behavior. Thus, the idea is that if we know the former we can predict the latter. However, polls are not good when we try to predict volatile behavior. More information about political awareness, engagement, and mobilization is needed. What we really want to do is to model changes in voting behavior given changes in politics, economics, demographics, and attitudes. Thus, some additions are needed to our toolkit. The ones here covering a polling of the polls and panel and spatial data are worthwhile.

Conclusion

Ironically, Ukrainian pollsters have spent great resources collecting samples of 10 thousand, 11 thousand, or even 30 thousand respondents. However, having only three panels with 3,000 respondents and a set of contextual variables would be so much better for predicting elections. Of course, there are explanations for such enormous sample sizes. Polls have to cover many small administrative units, and there is a demand among local political players to know what is happening in their constituencies. Nevertheless, if someone has resources to run a survey for 10 thousand respondents, they must have resources for three panels with 3,000 respondents as well. If analysts and political campaigners have resources and they show a desire to predict elections, why are we stuck with rudimentary polls? Perhaps new tools and techniques are hard to find in the masses of digital information. I hope the ones presented are helpful, and that scholars, pundits, and campaign managers give attention to them (and share among researchers others they may find) in order to build better analyses and more efficiently inform candidates how to spend their resources.

Tymofii Brik is Assistant Professor at the Kyiv School of Economics and an Editorial Board Member of VoxUkraine.