(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) In addition to the obvious healthcare and economic challenges that COVID-19 presents to city governments in the Arctic region, it is also a communications and governance crisis. Accomplishing any task in Arctic cities is particularly complicated due to the specific conditions of the region. In particular, Arctic populations must contend with sheer remoteness, extreme cold, a rapidly changing climate, insufficient medical and infrastructure facilities, and heavily resource-based economies. To respond effectively, city leaders need to coordinate an integrated response that cuts across all sectors of urban life such as retail, dining, transportation, and education. In the face of federal inaction in Russia and the United States, local authorities from Murmansk to Juneau have had to take the lead in keeping their populations safe. An ability to deliver effective communications that encourage trust has been the main driver in both cases.

Balancing Economics and Health

For the Arctic region, like elsewhere, the key to surviving the pandemic is balancing health concerns with the need to keep the economy moving forward. The most natural strategy for the remote, poorly resourced Arctic cities is keeping the virus out by minimizing the number of outsiders coming into the region. Since there are only a limited number of hospital beds and physicians in the far north, the main pandemic response seemed to be prioritizing medical advice to limit interactions.

This strategy was especially important since the Arctic countries number among those with the most cases in the world, including the United States, Russia, and Sweden (where the initial response to the pandemic allowed more spread than in neighboring Scandinavian countries). While the northern regions of Russia and the United States seemed to fare better than the other parts of their countries, at least initially, they could not avoid infections.

Russia’s Arctic cities have some advantages over their Western counterparts, including the fact that they have more physicians per capita than similar cities in the far north in the West. Among their disadvantages, though, is that the Russian cities are much more compact than their Western counterparts. While this feature of urban design can be useful in reducing energy use per capita and making it easier to operate public transportation, in times of the pandemic, the closer living quarters can facilitate the spread of the virus among the population.

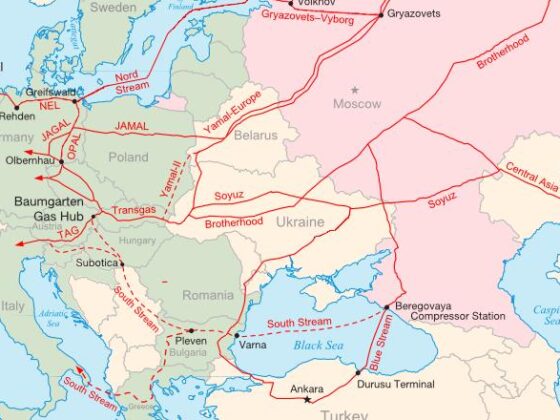

For Russia, the main source of the spread was workers arriving from outside the Arctic to work on the region’s burgeoning fossil fuel exploitation sites. The most important of these included the Kola Yard construction site in Belokamenka (Murmansk Oblast) focused on natural gas, the Chayanda oil field (Sakha Republic), and the Olympiadinskaya gold mine (Krasnoyarsky Krai). Reports from family members of workers employed at Kola Yard said that Novatek, the firm operating the site, failed to provide adequate personal protective equipment and the workers lived in crowded dormitories during their stay at the site. Problems at the construction center drove the first round of infections in Murmansk Oblast.

In Juneau, the main source of infection seemed to be people celebrating in bars on the 4th of July. One worker then spread the virus to his colleagues at a nearby seafood-processing plant, leading to a large outbreak. Once the virus arrived, working conditions in the plant facilitated its spread. While the resource-based companies were the source of problems at first in both Russia and Alaska, they have more recently seen a rise in cases driven by a more general community spread.

Regional Governments on Their Own

In both Russia and the United States, federal leaders largely ducked responsibility for addressing the crisis. Rather than developing a coherent and unified national response, they passed on these tasks to regional and local leaders to make their own policies in dealing with the situation. The result in both countries was a patchwork of efforts, with some regions doing better than others.

In the absence of an effective national policy, the key to responding successfully to the pandemic in Arctic conditions requires integrative leadership at the city level that is able to coordinate and implement policies across a wide range of areas. Our analysis of the initial COVID-19 response in Juneau, Alaska, found that this kind of response was crucial in keeping the number of cases low. Juneau has a relatively weak mayor, strong city manager, and a nine-member city assembly. The city has significant advantages in its efforts to manage the crisis because it owned the local airport and hospital and worked closely with the school system.

Nevertheless, despite this comprehensive system, the city authorities wished that they had been better able to coordinate the local response. Allowing some operations at local restaurants and bars undermined the ability of the school system to open to in-person teaching. And, despite the common ownership structure, both the hospital and airport had interests that did not always coincide with the comprehensive pandemic response. The hospital needed to protect its bottom line at a time when the pandemic had prevented it from engaging in many money-making activities while the airport sought to provide continuing travel services.

In the city of Murmansk, there is a strong city manager, weak mayor, and 30-member city council. With local power concentrated in the hands of city leaders and close ties with the regional governor, the structural foundations exist to develop more integrated policies. But Russia’s city governments are much less representative of their populations since they rely largely on appointments from above and controlled access to the ballot, which eliminates candidates whom the authorities do not support. The result is that the population has little trust in their leaders.

Russia’s system is designed to subordinate the local authorities to the governor as part of the power vertical that ultimately reaches up to the Kremlin. Nevertheless, even though Murmansk’s city manager is appointed from above, in order to rule effectively he must be able to demonstrate the effectiveness of his policies and build support for them among the local elites and the broader public. Developing this kind of buy-in is extremely difficult in both democratic and authoritarian systems.

Communications

Central to providing integrative governance during the pandemic is the authorities’ ability to communicate with their audiences. The key here is changing behaviors. Doing that naturally requires that the citizens trust the communications that they are receiving. Given the declining lack of trust in traditional institutions around the world, city leaders both in Russia and the West faced considerable challenges in getting their message out and ensuring that the audience not only hears it but takes action in response.

Research on emergency communications from government authorities has a long history. Since the 1950s, when Elihu Katz and Paul Lazarfeld published their classic Personal Influence, it has been clear that the power of a message from the authorities to their citizens is often influenced by how a person’s friends, neighbors, and social networks interpret that message and whether they support it or not. Ongoing research continues to build on those insights, expanding them to include consideration of social media and applying them to conditions of disaster response. Today’s messages from the authorities are mediated by the lens of social media as well as in-person networks, making the state communicators’ job even more complicated than in the past.

At the same time, considerable research demonstrates that there is less trust in the traditional media both in authoritarian and democratic systems. Russians have been shifting their information consumption habits away from state-controlled television channels to freer sites that are available on the internet. The same is happening in the United States as citizens are less willing to believe what they hear from traditional news sources and increasingly seek out information from other places.

Local Arctic governments have responded to these changing patterns in information consumption by seeking to communicate directly with audiences. Murmansk Oblast authorities created an online data portal to present clear information about the number of cases and deaths in the region. While there is certainly reason to doubt the accuracy of the numbers posted online, the portal at least gave a sense of what the authorities saw as the main problem. For example, in late August, the portal provided the numbers of people infected at the Belokamenska construction site as well as in the Oblast as a whole. Viewed on November 28, the site showed a rapid increase in cases since the end of the summer, with the number of infected more than doubling. While the portal still showed the number of cases from the construction site, it was clear that this location was no longer the main driver of infection in the region and that other sources had surpassed it.

Alaskan cities like Juneau had similar sites with similar statistics marking the progress of the pandemic and the alarming increase of cases in the fall. Juneau had also invested in producing a variety of informational flyers that city workers had posted around town to get the authorities’ message out.

In both Russia and the United States., city managers sought as many avenues for communicating directly with their constituents as possible. For example, Murmansk City Manager Yevgeny Nikora included a profile picture of himself on Facebook with a mask, sending the message that he supported such protective efforts.

In Juneau, the city manager addressed the population each morning on the radio with a 10-minute update about the situation and what needed to be done in response. These addresses proved popular with the citizenry, giving them a reliable sense of what was happening and the feeling that someone was in charge and taking necessary action to protect public safety. Juneau saw the importance of communications from the very beginning of the pandemic. As early as March, when the shutdowns first began, it increased its communications staff from half of a full-time employee to eight staff members working on getting messages out. This dramatic repurposing of personnel demonstrated how seriously the Juneau city and borough governments took the communication problems.

Indigenous Concerns

In both Russia and the United States, Indigenous communities often live in a parallel universe separate from the settler communities that have developed Arctic cities. Memories of the 1918 Spanish flu remain strong among Arctic Indigenous communities since the earlier pandemic had deadly consequences, and stories about its lethality were passed from generation to generation by community elders. Many of these groups are vulnerable to problems with the virus due to their even greater remoteness, limited social mobility, and narrow access to information and public services.

Typically, to protect themselves, the Indigenous communities sought isolation from settler communities by limiting access to their land. They continued with subsistence gathering of natural foods but suffered from a lack of economic contact with outsiders.

The situation of the Indigenous differs across the Arctic. In some cases in Alaska, Indigenous groups benefit heavily from local resource extraction and often have the resources to develop their own health care systems and coordinate their own response to hazards like the pandemic. In Russia, the government has frequently crushed autonomous Indigenous activity in coordination with its larger crackdown on non-governmental organizations. As Arbakhan Magomedov argues, Northern Indigenous groups have started to advocate more effectively for their interests, but they have not yet been able to extract major concessions from the authorities.

Conclusion

A dangerous winter approaches. The early onset of cold and darkness in the north has only exacerbated the situation for regional and local leaders as cases have spiked to levels not seen since the beginning of the pandemic. As the growing caseload requires additional shutdowns, the economic impact is expected to grow. Increasingly, local leaders are looking to the federal government for additional economic assistance and support for both public and private sector operations. However, it is not clear that federal governments in either Russia or the United States are willing or able to provide the kind of aid that local leaders and citizens would like to see.

The ongoing pandemic and lack of outside financial support will provide a clear test for local resilience in parts of the countries already facing extreme conditions. As the spread of the virus increases toward the end of 2020, in addition to the usual cold, remoteness, and changing climate, city leaders will have to muster all of their resources to ensure that their constituents are able eventually to restore their accustomed lifestyles.

Robert Orttung is Research Professor of International Affairs, IERES, and Director of Research, Sustainable GW, at the George Washington University. Acknowledgement: This report draws on information and analyses developed with the support of U.S. National Science Foundation Award #2028348.

[PDF]