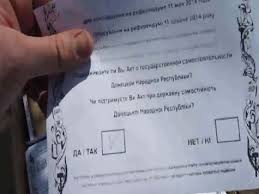

(IISS) The so-called referenda in Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk regions over the weekend are widely seen in Western capitals purely as a prelude to further Russian aggression. Certainly, further incursions into Ukrainian territory cannot be ruled out, particularly given what seems to be the long-term stationing of a massive strike force just across the border. But events in Ukraine demand that Western governments be as concerned about a ‘Bosnia scenario’ as they are about a ‘Crimea scenario’. Unfortunately, that does not seem to be the case.

No historical parallel is a perfect match, and in this case – a potential future development analogised to one in the past – the differences are myriad. But the inter-communal violence that broke out as a newly independent Bosnian government attempted to assert control should serve as a warning sign. That conflict also began when a hostile neighbour (Yugoslavia) incited and assisted its compatriots (Bosnian Serbs) in a drive to gain autonomy from the new central authorities, who initially resisted power-sharing arrangements. This political dispute spiralled into mass inter-communal violence. Tens of thousands were killed and millions displaced.

Inter-communal violence in Ukraine has so far been on a much lower level than that of the mass killings that occurred in the 1992–95 Bosnian War. And the inter-communal lines in Ukraine are more political than ethnic; this conflict is mostly among an ethnically homogenous Ukrainian population. Self-identifying ethnic Russians made up only 17% of the population, according to the last Ukrainian census, and many of them live in Crimea. The dividing lines in Ukraine relate to how power changed hands in late February (some see it as a popular revolution, others as an armed coup) and the legitimacy of the new government, which is dominated by representatives of the four former Hapsburg provinces in the west of the country. Most Ukrainians in the south and east who oppose the government do not want to be part of Russia, but neither do they want to be ruled by the current Ukrainian government.

And political divisions can be no less potent a cause for bloodshed. Indeed, Ukraine has experienced multiple atrocities in recent months. The first came when dozens of participants in the Maidan protests – some armed, most not – were mowed down by sniper fire in January. The most recent was in Odessa, a historic port city. There, on 2 May, after an altercation between pro- and anti-government groups following a football game, more than 40 anti-government protesters were killed as their opponents set fire to the building in which they had taken refuge. Some were killed by bullets and fists as they tried to escape the flames.

Russia’s role in Ukraine’s unrest is clear, and there’s a strong case to be made that the recent violence might not have occurred if Russia had neither annexed Crimea nor assisted the separatists. But ‘who started it?’ is a question for scholars and lawyers, not policymakers. Western governments should not be blind to the internal conflict in Ukraine that, even if Russia does not repeat the Crimea scenario, could tear the country apart from within.

Instead, those governments, and Washington in particular, seem too busy searching for the hand of the Kremlin to notice what is going on. In congressional testimony last week, a senior US official had only this to say about Odessa: ‘it should come as no surprise that, in Odessa, the Ukrainian authorities report that those arrested for igniting the violence included people whose papers indicate that they come from Transnistria, the Crimea region of Ukraine, and Russia.’ There was no condemnation of the mass killing, nor condolences for the victims. And, regardless of the as-yet-unproven allegations about the identity of ‘those arrested for igniting the violence’, all the dead that have been identified were Ukrainian citizens and residents of Odessa.

Meanwhile, rather than negotiate with the separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk, the Ukrainian government has launched what it calls an ‘anti-terrorist operation’: the use of the regular military and the newly created (and presumably poorly trained) national guard, supported by pro-government paramilitaries, against the armed anti-government forces that are occupying official buildings. Any government has the right to assert its writ on its own sovereign territory. But this operation is being conducted in regions where the population was already overwhelmingly opposed to the government in Kiev. A mid-April poll indicated that over 70% of the population in both Donetsk and Luhansk consider that government ‘illegal’. A separate poll, conducted in the same period, indicated that over 80% of respondents in those two regions believe that the government did not represent all of Ukraine.

Many of these Ukrainians don’t want armed, pro-Russian irregulars roaming the streets. But they have reacted even more strongly to the anti-terrorist operation, with civilians’ attempting to block military vehicles and many insulting, and some hurling blunt objects at, the troops. It’s no wonder the military cannot seem to hold much of the territory it clears.

Yet that operation has been implicitly endorsed by Washington, which is focused on supplying the military carrying it out rather than calling for restraint. Back in December, after a police attempt to break up the Maidan protest, the US secretary of state issued a statement expressing his ‘disgust’. He went on to say: ‘we call for utmost restraint. Human life must be protected. Ukrainian authorities bear full responsibility for the security of the Ukrainian people.’ Those words are even more appropriate today. But the focus on Russian aggression has the US government speaking from a different set of talking points.

See the original post © International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS)

Samuel Charap is IISS Senior Fellow for Russia and Eurasia. His article ‘Ukraine: Seeking an Elusive New Normal’ appears in the June–July issue of Survival.