(IISS) (Co-authored with J. Shapiro) The Ukraine crisis poses vexing policy challenges for Washington. President Obama has sought to strike a balance between the imperative of responding to Russian actions and the equally important need to avoid an all-out confrontation with Moscow. ‘It’s not a new Cold War,’ he said. ‘It is a very specific issue related to Russia’s unwillingness to recognize that Ukraine can chart its own path.’ The problem is that the administration’s balancing act cannot last long. As the dramatic deterioration of conditions on the ground in Ukraine in recent weeks has demonstrated, forces beyond the president’s control are pushing him toward the very New Cold War that he wants to avoid. He will eventually face a choice between that outcome, which will prove hugely dangerous and costly, or negotiating a solution to the crisis with Russia, which might hurt him politically but is far better for the country and the world. He should choose to move toward the negotiated outcome now.

Obama’s instinct to avoid the New Cold War is clearly the right one. Gratuitously seeking confrontation with Russia could lead to Armageddon after all. But more to the point, the US needs Russian cooperation on any number of other global priorities, particularly Iran, but also Syria, Middle East peace, Afghanistan and counter-terrorism. As long as Russia is willing to play ball on those issues, the US has every reason to continue to do so as well.

At the same time, the administration’s lack of interest in negotiating with Russia is also understandable. The potential for a success at the talks seems like a long shot at best, and the status quo, while unpleasant, is not hugely detrimental to US interests. Americans are not dying; the US economy is not affected; US treaty allies are safe.

The administration’s policy can be called the ‘middle way’ between these two extremes. It is defined by maintaining cooperation on key global issues while keeping up the pressure on Russia for its actions in Ukraine and supporting the new government in Kiev. It also is dependent on avoiding significant escalation on the ground in the Donbas and on the Kiev government managing to stay solvent.

The middle way seems prudent today. But it cannot last. Obama’s middle way will likely devolve into the very New Cold War that he is seeking to avoid. Politics in both Washington and Moscow and the interaction between them will make it be impossible to sustain over time in two key ways.

First, it will become politically untenable to avoid escalation in Ukraine while maintaining cooperation on global issues. For the US, this dual-track approach – condemning Russia as an aggressor one day, and seeking to work with Moscow the next – creates regular opportunities for Obama’s critics to decry him as weak and feckless. Indeed, cries of appeasement can be heard from Capitol Hill each time senior US and Russian officials meet to discuss global issues, or when the Obama administration takes steps to avoid escalation in Ukraine. In Moscow, officials are regularly criticised for having betrayed the Donbas, or for being too soft on the US by cooperating on other issues, such as arms control. And since these political dynamics play out in public and are picked up by the other side in real time, the hawks in each country tend to feed off each other, progressively raising tensions ever higher as time passes.

Second, both countries’ bureaucracies will prove incapable of resisting the urge to link their dispute in Ukraine to other aspects of bilateral interaction. The US began linking unrelated aspects of the relationship almost immediately after the annexation of Crimea in March 2014. All joint work considered non-essential – from the Bilateral Presidential Commission to most space cooperation – was suspended. But what remains of the relationship is therefore what matters the most to the US, from the Iran nuclear talks to the purchase of Russian rockets to launch US military satellites. Moscow has for the most part continued to cooperate on these issues, compartmentalising them from the Ukraine dispute. But this mutual compartmentalisation has already started to fray. In December, for example, Russia announced that it would not be attending the US-led Nuclear Security Summit. It is only a matter of time until the tsunami of tensions overwhelms the remaining islands of cooperation in the relationship.

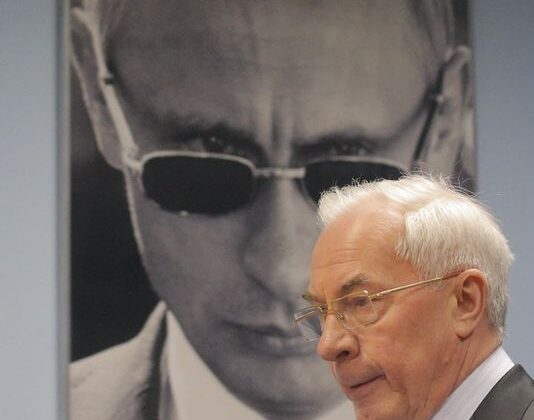

And those tensions will rise. As the past few weeks have demonstrated, Moscow is not content to let the conflict in Ukraine simmer on the back burner. Accepting even a rump Ukraine that is rapidly hurtling into the arms of the West and its institutions is a political non-starter in Moscow. So without a settlement that gives the Kremlin some of what it wants, we should expect that the current escalation of Russian support for the insurgency in the Donbas will not be the last. If the ongoing rebel offensive – or the next one – were to push deeper into Ukrainian territory, the political pressure to escalate US involvement through further sanctions and/or supply of lethal assistance to the Ukrainian military might prove overwhelming. Under those conditions, even if the US would like to continue to cooperate with Russia on global issues, Moscow might well balk, while further escalating its own involvement on the ground in Kiev.

But even if the conflict in eastern Ukraine were to be frozen in some form, with no bloodshed but also no settlement, the middle way cannot hold. It has already proven politically difficult for the Obama administration to continue working with Russia on key global issues. Senator John McCain has called it ‘a strategy worthy in the finest tradition of Neville Chamberlain’. It will only get harder as most of the presidential candidates—Democrat and Republican—appear set to run on a hardline toward Russia. A similar dynamic plays out in Moscow, where nationalists, now including some fighters who have returned from the frontlines in Ukraine, often criticise Putin for ‘betraying Novorossiya’ and denounce his ‘Chekist-oligarchic regime’. Hardliners publicly call for Russia to renounce arms-control treaties and to end all cooperation with NATO.

Let’s assume that those political forces can be kept at bay for a while. The middle way would still face a key challenge: time. It is explicitly a temporary policy, in place until Putin and his regime give in to Western demands to change course in Ukraine. As Obama said in December, ‘You'll recall that three or four months ago, everybody in Washington was convinced that President Putin was a genius … And I said at the time we don't want war with Russia but we can apply steady pressure working with our European partners, being the backbone of an international coalition to oppose Russia's violation of another country's sovereignty, and that over time, this would be a strategic mistake by Russia.’ In other words, the middle way is designed as a means to an end; it assumes that Western pressure will change Russian policy in Ukraine.

There is a debate about this assumption in Washington. But even those who agree with it do not see it as a short-term proposition; it’s a matter of many months, if not years, of squeezing Russia to produce results. The problem for the Obama administration is that the political dynamics pushing toward escalation, and the bureaucratic dynamics pushing for linkage will produce results in a matter of weeks or months at most. In other words, even in a best-case scenario, it’s just a matter of time before the New Cold War will overtake the middle way.

Eventually Obama will have to choose between the New Cold War and a negotiated solution to the crisis. Elsewhere, we have argued that such a solution would entail a new arrangement with Russiaon the regional security order in Europe. Such a deal would involve difficult compromises. It would probably entail recognition of a special Russian role in its neighbourhood, and an end to NATO and EU enlargement on Russia’s borders. But the alternative, the New Cold War, is far worse – for the United States, Russia, Europe and most of all for Ukraine. It is already past time to begin talks with Moscow on that new deal.

See the original post © The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS)