In Russia and throughout much of the post-Soviet space, media are now less free than at any point since the end of the Soviet Union. Authoritarian regimes across the region have deployed a range of tactics to control citizens’ access to information and their perceptions and interpretations of the information they do receive: hounding and marginalizing some media outlets, coopting others, and outright shuttering still others, as journalists are prosecuted, forced into exile and even murdered. Meanwhile, recent years and months have seen dramatic increases in both the pace and ferociousness of media repression, with important consequences for the future of post-Soviet politics and how Western and post-Soviet societies can interact.

Media control is central to autocrats’ ability to project dominance and competence, forge a social consensus, skew election results, and keep protesters off the streets. Without censorship, authoritarianism cannot persist. A growing literature on “informational autocracy” suggests that contemporary authoritarian leaders tend to prefer strategies of persuasion and cooptation over outright coercion. The range of media-control strategies available to autocratic regimes, coupled with Russia’s own coercive turn, raises important questions about the efficacy of contrasting approaches to censorship, as well as about the behavior of media consumers themselves.

Evidence from recent surveys in Russia and Belarus indicates that autocrats are most effective at promoting pro-regime news consumption and increasing their dominance of the information space when their interventions are least heavy handed. Where regimes opt for the wholesale destruction of oppositional media outlets, by contrast, citizens tend to seek out new sources of news ideologically similar to those that were targeted by the state for repression. As Moscow adopts an approach to media control that relies more heavily on extreme coercion, these findings suggest that the Kremlin’s attempts to control the Russian media space will become less effective, not more.

The Russian Case

After an initial period of liberalization in the 1990s—during which Russia saw the blossoming of independent and editorially diverse media, whose influence easily outstripped state-linked media—Vladimir Putin began his presidency with an almost immediate attempt to shift the balance. Less than a year and a half after taking office in January 2000, he had engineered the transfer of control over the country’s two leading television channels, NTV and ORT, to owners controlled by or loyal to the state.

Putin’s takeover of NTV and ORT set in place a model of media control that would endure for two decades. Rather than outlawing or dismantling media deemed to be problematic, the Kremlin worked to cajole and coopt media into servility. It built a system of “curators” with responsibility for instructing publishers and editors on the Kremlin’s news agenda and preferred interpretations and identifying commercial pressure points sufficient to encourage compliance. Those media that refused to take part in this system of curation were largely allowed to persist, but they were locked out of commercial distribution and advertising systems and barred from obtaining broadcast licenses.

The Kremlin’s initial focus on dominating the TV airwaves, however, meant that for a time, diversity of reporting and opinion was able to flourish in newspapers and online. After Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, the Kremlin’s sensitivity increased—but the model for extending control into the print and online space remained the same. Thus, in 2014 the Kremlin encouraged billionaire Alexander Mamut to fire the editorial leadership of Lenta.ru, which had played an important role in the 2011-12 For Free Elections protest movement and was promoting critical coverage of Russian actions in Crimea and Donbas. Two years later, the Kremlin arranged the sale of the RBK media holding after journalists there published an investigation into the wealth of Putin’s daughters. In 2019, Kommersant fired two reporters after they published an investigation into Federation Council Speaker Valentina Matvienko, leading to the resignation of the entire political team (billionaire Alisher Usmanov was a shareholder of the newspaper). And in 2020, the senior staff and most of the newsroom of Vedomosti resigned after ownership of the newspaper was transferred to Kremlin-friendly shareholders.

As a result, Russia entered Putin’s third presidential term with a large state-dominated media space across broadcast, print, and Internet (such as Channel 1, NTV, Komsomol’skaia Pravda, LifeNews, and the official state media holding, Sputnik), a small but boisterous ecosystem of print, radio and online media outlets in outright opposition to the Kremlin (such as the online broadcaster Dozhd, the radio station Ekho Moskvy, the print periodicals Novaya gazeta and The New Times, and, soon thereafter, the online news site Meduza), and a handful of outlets (including Kommersant, Vedomosti, and RBK) seeking to occupy a middle ground.

Things changed, however, beginning in 2020, at the same time that the Kremlin began to take a much harder line against the political opposition. Violent crackdowns on protesters, the attempted poisoning and subsequent imprisonment of opposition leader Alexei Navalny, the expansive use of laws against “Foreign Agents” and “Undesirable Organizations,” and the outlawing of key opposition organizations would have inevitable consequences for journalists, too. By mid-2021, most major (and even most minor) independent news outlets had been declared foreign agents. The advent of full-scale war against Ukraine in February 2022 brought even more draconian restrictions, including 15-year jail sentences for those who reported anything other than the official line on the invasion, the shutdown of Dozhd and Ekho Moskvy entirely, and the blocking of online access to Meduza and other websites, as well as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

The Belarusian Case

Unlike Russia, Belarus never saw a significant period of media liberalization. While Belarus’s first post-Soviet government, under President Stanislav Shushkevich, took a reasonably laissez-faire approach to the media, and independent newspapers grew out of old dissident organizations, Aliaksandr Lukashenka sought to reestablish a Soviet-style model of media control upon taking office in 1994. His government maintained political censorship of state-owned newspapers and broadcasters and filled key posts with political appointees. The state retained a monopoly on terrestrial broadcasting and heavily subsidized state-owned newspapers, including Sovetskaya Belarus and Belarus Segodnia. Independent media were limited to the radio (chiefly, Euroradio), satellite/cable television (chiefly, Belsat), and newspapers (chiefly Narodnaya Volya and Belaruskaya Delovaya Gazeta). By 2010, however, pressure forced both of the leading independent newspapers to shut down.

As independent journalism in Belarus gradually migrated to the Internet, the sources of pressure that allowed the state to drive Narodnaya Volya and Belaruskaya Delovaya Gazeta out of business—depriving them of advertising revenue and distribution networks—were no longer sufficient, and overt forms of coercion became increasingly prevalent. In the run-up to the 2012 elections, journalists faced a hitherto unprecedented wave of arrests, fines, and imprisonments based on laws banning criticism of government officials and circumscribing non-state outlets’ right to cover political, economic, and social issues. When these restrictions failed to reduce both independent journalism and growing protests over economic issues in 2017-18, some 100 journalists were fined, according to Reporters Without Borders. And during the COVID-19 pandemic, journalists accused of fear-mongering were harassed, detained, fined, and beaten.

The typical pattern was repeated in the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election, with preventative blocking of access to news websites and the preemptive arrest of some 40 journalists. When that again failed to prevent protests—in this case, a wave of protests so large and so encompassing that it required several months and the assistance of Russian riot police to quell—the state ramped up the repression, detaining nearly 500 journalists and subjecting some 69 to beatings and torture. The authorities effectively blocked the most popular independent news website, Tut.by, which almost immediately reestablished itself as Zerkalo. At the same time, the Telegram and YouTube channel Nexta persisted despite the arrest of its editor, Raman Pratasevich, when the Ryanair jet on which he was flying from Greece to Lithuania was forced to land in Minsk. Nevertheless, within a year, any remaining independent journalists were imprisoned or forced into exile, and access to independent news sources was possible only via VPNs (virtual private networks).

Survey Results

The two contrasting approaches to media control and censorship in Belarus and Russia—one focused on coercion, and the other, until recently, focused on curation and cooptation—have given rise to two very different media systems, and two very different structures of media consumption. Surveys conducted in August 2019 and March 2020 in Russia and September 2020 and September 2021 in Belarus, using largely identical questionnaires and approaches, reveal starkly different degrees of polarization and divergent patterns of response to censorship among Belarusian and Russian citizens.

Among other questions, respondents in all four surveys were given lists of major media outlets across the political spectrum in their respective countries and then asked to indicate the frequency with which they turn to each of the outlets for news. Rather than asking people directly about their political orientation, this allowed respondents to be grouped organically by preference: those who reported more state-linked media than independent media in their news diet were marked as preferring state media, and those who reported consuming more independent media were marked as having that preference.

The first finding of note, then, is the relative popularity of independent media in Belarus, which far outstripped their Russian counterparts. Thus, in the first Belarusian survey, 50 percent of respondents preferred independent media, versus 27 percent who preferred state media. That contrasts with Russia, where fully 80 percent of respondents preferred state media, versus 20 percent who consumed more independent media. The difference is particularly striking for the largest television channels: only 43 percent of Belarusians reported watching ONT with any regularity, versus the 73 percent of Russians who reported watching Pervyi Kanal.

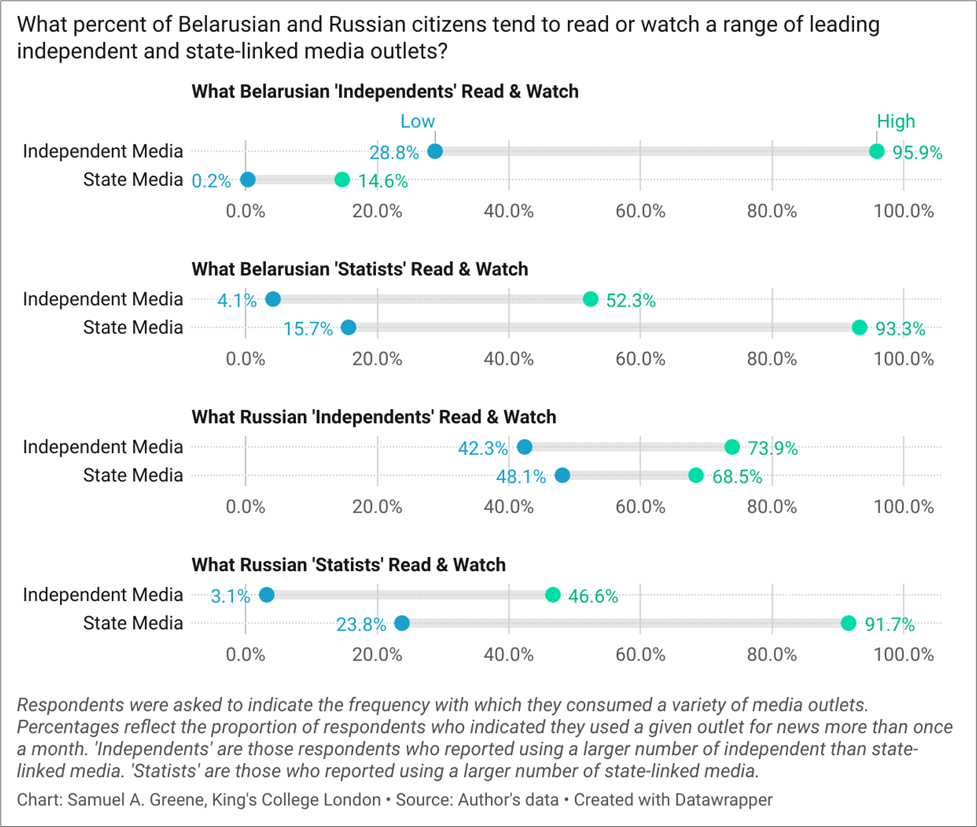

Secondly, while media audiences in Belarus are clearly polarized, Russian media audiences appear much less so. Thus, among those Belarusians who preferred independent media, the median state media outlet was consumed by only 7 percent, and the most popular state outlet by only 15 percent. Those Belarusians who preferred state media were more likely to consume at least some independent media, with the median independent outlet being used by 21 percent of “statists” and the most popular in 2020 (Tut.by) being used by 52 percent. There was much more overlap among Russian respondents, however. The median state-linked media outlet was consumed by 54 percent of independent-media-minded Russians, and the most popular (Pervyi Kanal) was consumed by fully 69 percent. Those Russians who preferred state media were somewhat less omnivorous: the most popular independent outlet (Ekho Moskvy) garnered an audience of 47 percent, while the median opposition outlet was consumed by only 14 percent of Russian “statists.”

In other words, as Figure 1 shows, Russian media consumers have significant exposure to media across the political spectrum, regardless of the individual citizen’s own political preferences. Meanwhile, Belarusians—particularly those who prefer independent media—have very little exposure to the opposite side.

Figure 1. Media Audience Polarization in Belarus (2020) and Russia (2019)

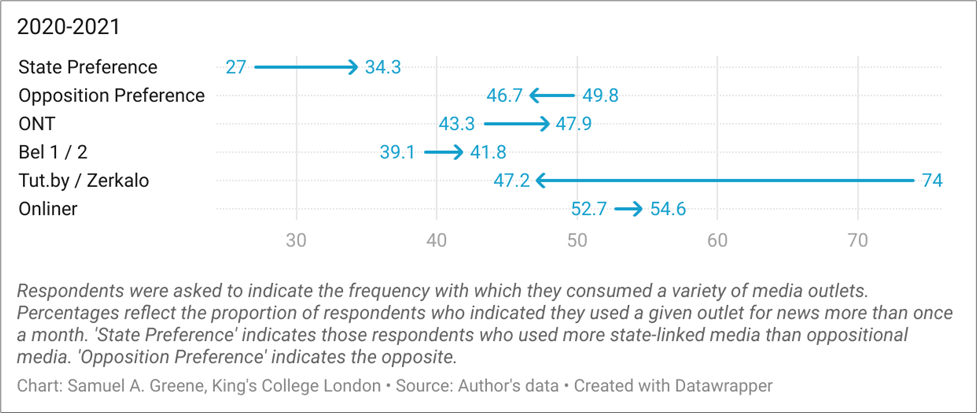

Changes over time allow us to see the effects of contrasting approaches to media control with more clarity. As noted above, prominent oppositional media outlets in both countries were targeted for repression between the two survey waves. In Belarus, authorities outlawed and blocked access to Tut.by, and while it reconstituted itself as Zerkalo almost immediately thereafter, its audience dropped from 74 percent of respondents to 47 percent. In Russia, meanwhile, political pressure and shifts in ownership led to the wholesale replacement of the editorial team at Vedomosti. Unlike Tut.by, however, Vedomosti’s audience share in the Russian surveys actually increased marginally, from 25 percent to 27 percent.

No more than 8 percent of Tut.by/Zerkalo readers reported turning their attention to any of the state-linked media outlets on the list. Instead, former Tut.by readers turned to other oppositional media, including Onliner, Belsat, and Nexta. As a result, even as the volume and frequency of media consumption declined in Belarus from 2020 to 2021 and entertainment drove some viewers back to state television (see Figure 2), the average Belarusian who preferred independent media consumed 4.31 media outlets in 2021, versus 3.47 in 2020—and virtually all of that increase in consumption accrued to independent media. (Indeed, the number of state media in the average independent media consumer’s diet fell from 1.01 in 2020 to 0.79 in 2021.)

Figure 2. Changes in Belarusian Media Audiences

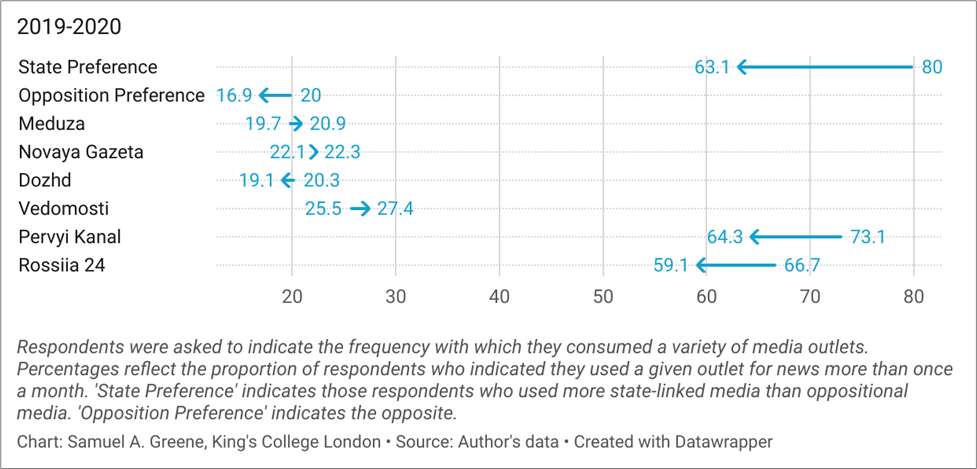

In Russia, the picture could not be more different. People who read Vedomosti in 2019 and decided to look for alternative or additional sources of news in 2020 turned in much greater measure to state-friendly media such as Pervyi Kanal (27 percent), Rossiia 24 (29 percent), or Lenta.ru (27 percent) than to independent media such as Ekho Moskvy (18 percent) or Novaya Gazeta (15 percent) or Dozhd (13 percent). Overall, consumption of both state-linked and oppositional media declined in Russia from 2020-21, as publications like Vedomosti were pushed into a grey zone between independence and servility, and many audience members followed them there (see Figure 3). Among those Russians who preferred independent media, the average number of independent news outlets consumed fell from 4.94 to 3.53, while the average number of state-linked outlets consumed grew from 2.53 to 3.58.

Figure 3. Changes in Russian Media Audiences

Conclusions

The findings described here strongly suggest that “softer” strategies of media cooptation are more effective than harsher, more coercive approaches to media control. In Russia, where the Kremlin has—until very recently—used a combination of commercial pressure and political influence to push media owners and editors towards cooperation, the result has been a media system in which even those Russians who prefer independent media have broad exposure to the Kremlin’s messaging. Moreover, as the Vedomosti case demonstrates, softer repressions against uncooperative media outlets seem to afford the Kremlin an opportunity to capture the attention of a large portion of those outlets’ audiences.

By contrast, the heavier hand wielded by authorities in Minsk has helped create a highly polarized media system, in which oppositional media—despite massive repression—capture more audience attention than state-linked media, and consumers of independent media have very little exposure to state messaging. Attempts to stifle independent media outright only suffice to put oppositional audiences even further out of the reach of the state.

Given recent developments in Russia, the Kremlin may want to take notice of Lukashenka’s struggles in the media sphere. Russia’s pre-2021 approach to media control allowed for many media outlets and perhaps most media consumers to exist in a grey zone, in which oppositional messages could not be entirely excluded but in which few oppositional citizens could be impervious to state messaging. Moscow’s current tack risks undoing that, pushing oppositional media consumers into a space beyond the state’s reach, even as audiences for state television continue to decline. As oppositional audiences grow, Putin—like Lukashenka—will find it increasingly difficult to win them back.

However, the flip side of that process poses a challenge for Western policymakers, too, for those who would seek to support democratic movements in Russia and Belarus, and for those democratic movements themselves. While avenues for communication with Russian and Belarusian democratic movements are clear and, for the most part, open, pro-democracy constituencies will find it increasingly difficult in a more coercive and more polarized environment to make inroads with consumers of state-linked media. In a more softly controlled media environment like Russia up to 2021, audiences across the spectrum are exposed more or less to the same news agenda, with differences pertaining mostly to interpretation. In more restrictive environments—like Belarus or like Russia from 2022 and likely into the foreseeable future—news agendas themselves diverge. Audiences, as a result, find themselves not engaged in a debate across political divides but walled off into largely separate and mutually impenetrable conversations.

Samuel Greene is Professor in Russian Politics and Director of the Russia Institute at King’s College London.

Image credit