On November 27, 2018, the leaders of the 11 Cossack hosts convened in a hall in Moscow and agreed to establish an “All-Russian Cossack Organization” into which they would be integrated. This was followed by presidential decrees a year later formalizing the establishment of the organization and appointing Nikolai Doluda as its head. Since that time, the Russian Cossack movement has been very active, including promoting itself as a military reserve force. They are playing military and ancillary roles in the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, with some of Doluda’s remarks suggesting he knew about the planned date of the invasion.

What were the precursors of Russia’s Cossack movement, and how can we understand the nationalization of what had been historically a regional identity group? What does the increasing popularity of the movement augur for the future? Russia’s Cossack movement has undergone a process of widening and deepening, spreading from Russia’s South to practically the entire country and taking on new roles in the process. Its provision of security and educational organizations have grown, along with academic publications focusing on them. All three indicators demonstrate the institutionalization of the movement following Putin’s return to power in 2012. Today, the Cossacks act as a social mooring for the regime, anchoring conservative morality in Russian society.

Cossacks, Free and Registered

While there is no certainty as to the precise number of people with Cossack heritage in Russia, most estimates put it at close to 7 million (it is also an identity group shared with and claimed by Ukraine). Persecuted by the Bolsheviks, the Cossacks were once again allowed openly to celebrate their ancestors with the 1990 decree on the rehabilitation of repressed peoples and, more significantly, with the 1991 decree on the rehabilitation of repressed peoples in relation to Cossacks. In 1995, Boris Yeltsin introduced a state register of Cossack organizations under some pressure to do so from Cossack revival movements principally in the Rostov and Krasnodar regions. Thus began the most significant split for the Cossacks today—namely between registered and “free.”[1]

Those who are “free” claim to be Cossacks due to their ancestry and being descended from Cossack stock, whereas those who have registered do not have to demonstrate ancestry before signing up. This division, reminiscent of those made earlier in the Tsarist era, is most relevant only for classification purposes considering the two groups share instinctive patriotism and love of country. The analysis here is on the ”registered” Cossacks, who were divided into 11 hosts—a 12th one was added after the inclusion of the Black Sea Cossacks in Crimea—spanning the territory of Russia and typically named after natural features such as rivers rather than administrative regions of the country. They are the Don, Kuban, Terek, Central, Volga, Orenburg, Siberian, Zabaikalsky, Ussuri, Irkutsk, Yenesei, and Black Sea. Such a nomenclature harkens back to the Cossacks’ Tsarist-era role as forgers of empire. Service Cossacks provide numerous social functions as part of their duties, most notably with public order.

Patrols and Security

Cossack movements are well known for providing security patrols (druzhini) in Russian localities. The patrols are typically deputized to receive budget funds from the respective regions and provide a visible law enforcement presence in cities. Ostensibly first formed to reduce the likelihood of terrorist attacks, the Cossack patrols are now designed to deal with petty crime and hooliganism. The patrols are useful to the regional authorities to commit actions not permitted under Russian law—as Krasnodar Governor Aleksandr Tkachov put it, “What the police can’t do, a Cossack can.” There are numerous accusations that the patrols are rough on migrants from Central Asia and the Caucasus, the LGBTQ community, and ideological enemies of the regime (similar to other law enforcement organizations in Russia). The national origin of the patrols seems to date back to the 2005 federal law “On the Civil Service of the Russian Cossacks.” Table 1 below gives a selection of Russian cities and the dates when patrols first started in them.

Table 1: Dates of Initial Cossack Patrols in Russian Cities

| City | Host | Date of First Patrol |

| Rostov | Don | 1999 |

| Krasnodar | Kuban | 2012 |

| St. Petersburg | Central | 2012 |

| Moscow | Central | 2012 |

| Chita | Zabaikalsky | 2014 |

| Orenburg | Orenburg | 2015 |

| Adygeia | Kuban | 2015 |

| Khabarovsk | Ussuri | 2015 |

| Kaliningrad | Central | 2016 |

| Tomsk | Siberia | 2021 |

Granted, the provision of “security” has long been a Cossack activity, such as the Kuban Cossacks’ policing of Meskhetian Turk refugees in the 1990s, but what is different is the formalization of the relationship with the federal authorities. As can be seen from Table 1, however, the first such formal patrols began in Russia’s southern region of Rostov, with regional law deputizing the patrols. While there were informal patrols in Krasnodar Krai before 2012, it was only at this point that they became official. Other regions of the country also acquired Cossack patrols in the early 2010s, including Moscow, Chita, and Orenburg. At the time of writing, the practice of druzhini patrols continues to expand in cities throughout Krasnodar Krai and in cities across the country, such as Tomsk in Siberia.

The patrols of Cossacks in uniform and sometimes riding horses are received differently by members of the public, with some making fun of them and some feeling genuine protection from the patrols. For those who see a comic atavism in the patrols of uniformed Cossacks like something out of the 19th century (the Russian word riazhenie or clownish is often used to describe them), the patrols are similar to those of any other law enforcement agency. In projecting Russia’s history as a source of inspiration for the future, however, Cossack patrols resemble similar movements from other fascist regimes.

Educational Organizations

One of the main functions of Cossack groups since their inception has been the education of youth. Cossack education is designed to instill values of patriotism, Cossack history, and physical exercise (sometimes styled as “readiness for military service”) into young people. Much of the training involves the proper handling of weapons and combat rehearsal. The first way in which Russian youth are engaged in such Cossack groups is through “Cossacks cadets corps,” which are voluntary youth organizations that might be thought of as similar to the Boy Scouts or Young Pioneers of the Communist era. Such organizations provide children with extra-curricular education in patriotic values, the opportunity to serve the state (normally fighting forest fires), and paramilitary training.

There is considerable prestige associated with such organizations and a rigorous selection process. The Cossack cadets corps host marches for students, recreating the atmosphere of militarism. Table 2 provides dates for the earliest establishment of Cossack Cadets Corps throughout Russia, based on a preliminary analysis of available data. It seems evident there is a pattern of such youth organizations being established early in traditional Cossack lands and becoming more popular and widespread after Vladimir Putin’s ascent to power.

Table 2: Dates of Establishment of Cossack Cadets Corps

| Host | First Cadets Corps |

| Kuban | 1994 |

| Don | 1995 |

| Terek | 1996 |

| Zabaikalsky | 2001 |

| Orenburg | 2005 |

| Far Eastern | 2017 |

| Moscow | 2002 |

| Ussuri | 2010 |

| Dikoe Pole (Luhansk) | 2018 |

| Siberian | 2004 |

Another way in which the Cossack legacy is used to educate children is through the establishment of Cossack schools. While the size of the schools varies, reports suggest that by 2017 some 85,000 schoolchildren had been educated in a Cossack school in Krasnodar Krai alone. In Rostov, at present, there are 622 Cossack educational organizations containing more than 100,000 students. Young Cossacks in Rostov are also being grouped into “Cossack hundreds” in a reminder of how they used to be arranged in Tsarist times.

Cossack classes first appeared in Orenburg in 1999, led by the efforts of Vladimir Chashin. The classes took the form of studying and emulating Cossack traditions, history, and sports. In 2009, the first Cossack school (named “Ataman”) opened in the city of Orenburg. Professor Elena Godovova at Orenburg State University reported that the school enrolls 180 students every year and, in 2009, participated in shooting and martial combat tournaments with competitors from across Russia.[2] By 2020, there were five Cossack elementary schools educating some 900 students in the Orenburg region alone, and more than 3,000 youths were involved in extra-curricular Cossack education.[3] The bulk of the training is designed to help students take on careers in the armed forces and in the domestic security services of Orenburg Oblast.

Clearly, the movement is more populous in Russia’s South than in other regions. At last count, there were 27 municipal organizations with institutions with Cossack components. These include 15 in the South (Rostov, Krasnodar, Stavropol), three in the Central Cossack District (Moscow, Voronezh, Starodub), one in the North-West Federal District (Vologda), five in the Volga District (Penza, Samara, Syzran’, Ulianovsk, Ulianovsk region), one in Siberia (Novosibirsk), and two in the Far-Eastern Federal District (Both in Sakha).

Through social media and particularly VKontakte, young adults have retained their Cossack Corps connections. Competitions are popular. Cossack games, festivals (Sherimitsa or Spartakaids), and martial arts tournaments are held in each region. Recently, the Sherimitsa festival was institutionalized to culminate annually near the spiritual center of Cossackdom, Novocherkassk in Rostov. Likewise, Orenburg summer camps have been accepting hundreds of young people annually for games, education, and pre-military training.

The Salience of Cossacks in Academia

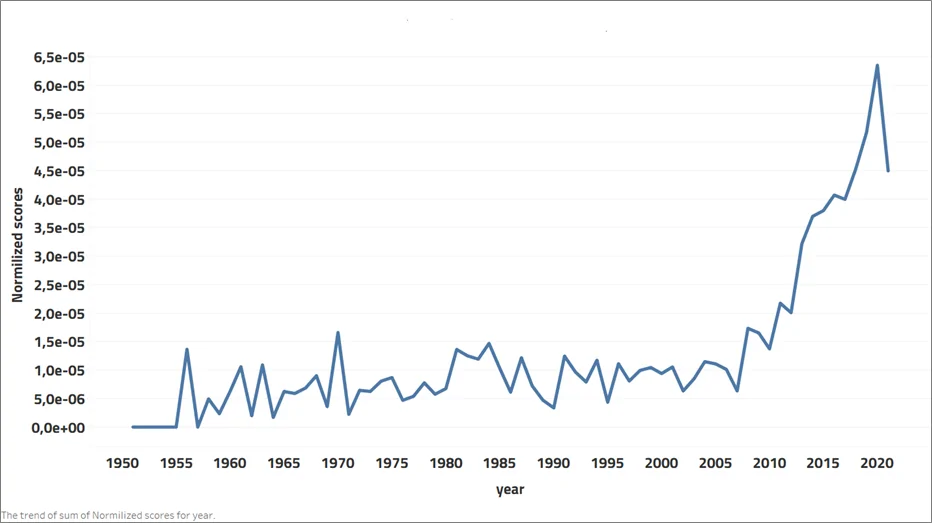

The expansion of the Cossacks described in the last two sections is also manifest in other ways. Figure 1 shows the normalized volume of academic publications focusing on the Cossacks. While still a tiny fraction of all publications, interest has clearly expanded enormously since about 2010 and most significantly since 2014.

Figure 1: Scholarly Interest in the Cossacks

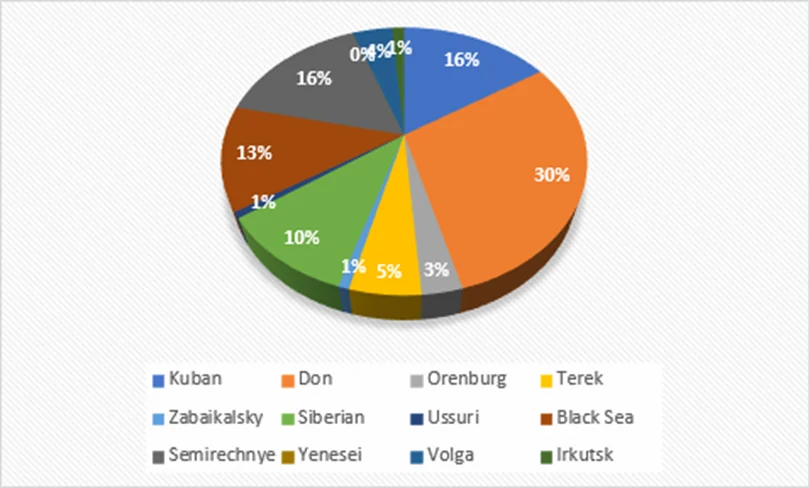

Although Cossack descendants are spread throughout the country as a result of modernization and the dislocation of peoples, the movement is still strongest in the southern regions of Krasnodar, Rostov, and Stavropol. To demonstrate this, Figures 2 and 3 measure the salience of “Cossack” in scholarly work since 1990. [4]

Figure 2: Salience of the Term “Cossack,” by Host, 1990-2022

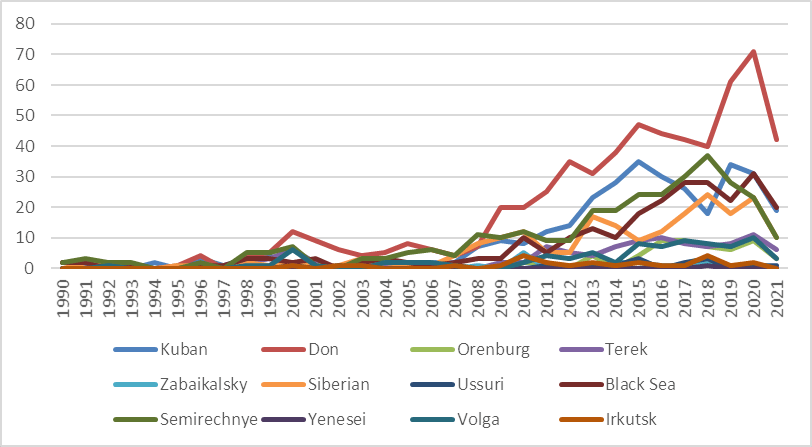

Figure 3 below demonstrates that scholarship on nearly all Cossack hosts is a recent phenomenon, originating from the movement in the Medvedev interregnum, if not a little before.Certainly, the hosts in Rostov and Krasnodar have received more attention than those with more marginal claims to be areas of traditional Cossack settlement, such as Orenburg and the Trans-Baikal (Zabaikalsky) region.

Figure 3: Scholarship on Cossack Hosts by Date of Publication, 1990-2021

Nor is it just in publications that the Cossacks have penetrated higher education. Several universities, too, claim a Cossack affiliation. The first Cossack faculty at a university came in 2011 in the Cossack Faculty at the Higher Eurasian University in Moscow. The Razumovsky “First Cossack University and Polytechnical Institute” in Moscow became affiliated with the Cossack brand in 2014 and grew to have branches in Penza and Kaliningrad. Aside from the name, however, there is little distinctly “Cossack” at the university. The Platov University in Novocherkassk (Rostov) had a center for the study of Cossacks, but funding was discontinued after 2014. The Southern Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAN) in Rostov has a laboratory for the study of the Cossacks, as does Bashkir State University and the Bashkortostan branch of RAN.

A 2021 agreement between the Orenburg Cossacks and the State University announced a collaborative project to integrate education for Cossacks who are protecting the environment. Finally, there is also a new Master’s program for the study of Cossack history being created at Taganrog State University, a campus of the Southern Federal University (formerly called Rostov State University). Such branding would be of little interest, however, until other activities in education and providing public safety are considered. Taken together, they suggest a coordinated attempt to institutionalize the Cossack identity.

Conclusion and Implications

The evolving Cossack movement in Russia is becoming comprehensively national, generating several implications for Russian politics.

First, the existence of the movement and its thorough social organization institutionalizes current power dynamics in Russia and creates a social base in support of the current system. Putinism may well survive Putin, in other words. At the same time, the movement can act as a gendarmerie in case of civil unrest. In the movement’s devotion to military training and palingenesis through violence and projective veneration of the past, it seems fascist.

Second, while Russia is far from the only authoritarian regime to seek to create popular support in society, the commandeering of the Cossack legacy represents a particularly Russian approach to doing so. Here, the Kremlin is playing with fire, as it could provoke a backlash from those who hold Cossack to be a nationality rather than an “estate.”

Third, the Cossacks offer the Kremlin foreign policy and hybrid warfare tools—different from the Wagner Group and other such mercenary entities—in that it is at least plausibly a grassroots movement. The Kuban Cossacks, who took part in the annexation of Crimea in 2014, for instance, are celebrated openly on the website of the (relatively) new All-Russian Cossack Society. They also offer the regime a soft-power foreign policy toolset by institutionalizing pro-Russian presences outside of recognized borders, appearing as cultural emblems of the country, and maintaining contact with diaspora organizations overseas.[5]

Fourth, the reconstruction of a national Cossack movement is further evidence of the country embracing its identity as a successor to the Russian Empire rather than the Soviet Union. The self-perception of a 19th-century nation-state may render comprehensible some of the country’s positions on “spheres of influence” and other topics.

Finally, the popularity of the Cossack movement may signal (whether a cause of or caused by) the improved fortunes of elites from the south of the country.

[1] Other than the distinction between Cossack separatists and patriotic Cossacks, Cossack separatism is a minority phenomenon and a topic for separate analysis.

[2] Elena Godovova, “Vzaimodeistve Organov Gosudarstvennoi Vlasti Orenburgskou Oblasti S Kazachestvom,” Agenstva Pressa, Orenburg, 2012.

[3] Elena Godovova and Volodymyr Chashin, “Deiatel’nost’ orenburgskikh kazach’ix obshchestv po stanovleniiu instituta kazachestva na sovremennom etape,” UDK 94, 2021.

[4] I omitted from analysis the “Central Cossack Host,” which is headquartered in Moscow and caters to descendants of Cossacks who left their region of origin due to “industrialization” because it does not claim to have historical antecedents. Furthermore, because the term “Central” is so common in other contexts, there were a large number of articles unrelated to the Cossack host. Trying to include the exact phrase “central Cossack host” resulted in no articles being returned, which confirms this coding decision.

[5] See: Richard Arnold, “The Role of Cossacks in Russia’s Soft Power Toolkit,“ PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 729, December 2021.

Richard Arnold is Associate Professor of Political Science at Muskingum University.