(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) In recent years, discussions about the political economy of U.S.-Russian relations have mainly been reduced to talks on sanctions and their effectiveness. A raft of Western sanctions, both multilateral and bilateral, imposed on the Russian economy from March 2014 continue to shave a few tenths of a percentage point from Russia’s annual GDP growth. The measures have steadily hampered Moscow’s ability to borrow from foreign capital markets and limited its access to western technologies and direct investments. This has also created greater risk and uncertainty for Russian companies and banks, leaving them toxic to many foreign partners. Russia has reacted by reducing imports of selected food products that, in turn, triggered ambitious import-substitution programs.

Paradoxically, the sanctions have not yet had a significant impact on the structure of U.S.-Russian economic ties, with the volume of bilateral trade in goods and services having returned to average pre-sanction levels. However, the recent G7 and NATO summits have confirmed a growing competition between two globalization models—Western and Chinese—built around different geopolitical concepts and diverging financial and technological platforms. Even if key trends persist in U.S.-Russian economic relations into the foreseeable future, as outlined below, the Kremlin’s rigorous anti-Western stance leaves Russia little choice but to move toward a “Pax Sinica,” albeit at a snail’s pace.

Emerging Economic Relations: Has the Mountain Brought Forth a Mouse?

In the last quarter-century, four main pillars of U.S.-Russian economic interaction have developed—trade in goods and services, integration of Russian companies into global supply chains, foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio investment, and shadow financial operations (which have continued to benefit Russian oligarchs and the country’s kleptocracy). Nonetheless, U.S.-Russian economic cooperation has never been considered appropriate or significant. Even in the best of times, Russia never ranked among the top twenty of U.S. trading partners and presently stands at twenty-sixth, having fallen behind Indonesia. The United States continues to be among Russia’s four leading import countries, but in the tenth position as an exports destination.

With the collapse of the USSR thirty years ago, there were expectations that Russia’s transition to a market economy would open new prospects and reverse the negative patterns established by Cold War times. The Soviet legacy had not been the best launching pad for bilateral business activity. To promote cooperation and improve the investment climate, a joint high-level bureaucratic coordinating mechanism was established in 1993, the Gore-Chernomyrdin Commission. It was able to move forward on several tracks, incentivizing collaboration in the space and energy sectors, high-tech, and agriculture. It also spurred the development of new legislation and bilateral trade and business agreements. However, after quickly exhausting its resources, the Commission turned into a sprawling, inefficient bureaucratic structure that was ultimately “buried” by the Russian financial meltdown of 1998.

Still, Washington and Moscow enjoyed a short honeymoon period after President Vladimir Putin ascended to power in 2000 and George W. Bush arrived in the White House in 2001. In the economic sphere, the focus was shifted to business dialogue, some of which proved rather successful, particularly in energy, trade in metals, and information technology (IT). Russia’s oil shipments to the United States started to rise steadily, and the country’s metal producers not only increased their share in the U.S. market but also made tangible investments, acquiring several American plants to become a link in the supply chain to the U.S. auto and aerospace industries. Russian IT firms struck some promising deals with U.S. high-tech enterprises and banks. During this time, several hundred U.S. companies entered the Russian market as well.

The establishment of clearer “rules of the game” in the banking sector, liberalization of currency regulations, and easing of capital flow restrictions expanded cooperation in finance. There were also encouraging signs that various Russian companies could be integrated into global supply chains. The construction of the Titanium Valley in the Urals, with the participation of Boeing and Russia’s VSMPO-AVISMA, was an impressive success story. It was a private initiative to manufacture high-quality titanium products for the global aerospace industry, whereby Boeing buys about 35 percent of its titanium from the Ural facilities, European Airbus up to 65 percent, and Brazilian Embraer almost 100 percent. Boeing invested several billion dollars in the production of highly specialized titanium forgings for civil aircraft by supplying Russia with sensitive dual-use equipment.

However, that visible part of economic ties has only been the tip of the iceberg—powerful shadow financial flows and exports through third countries have been hidden from official statistics. According to conservative estimates, the amount of money withdrawn from Russia and held in offshore havens was at least $800 billion in 2015. A significant share of those non-official foreign assets has been invested in the United States, including the real estate and the high-tech sector.

Is Politics in the Driver’s Seat?

Bilateral economic relations have always been in the shadow of political interchange. A community of experts has long noted the pronounced cyclical nature of Washington and Moscow’s political dialogue. Since the early 1990s, each new U.S. administration has made an effort to start with “a clean slate” to reignite relationships with the Kremlin, only to find most initiatives soon derailed, followed by a cooling period. The Trump administration’s attempt to reset with Russia failed before it started, and the 2021 Biden-Putin meeting in Geneva was unable to pursue a reset because of narrow overlapping interests and deep existing disagreements.

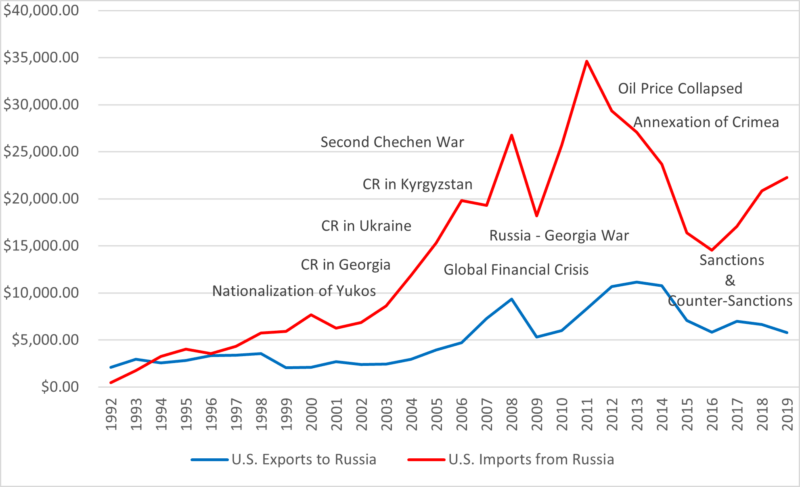

Less attention has been paid to the fact that in U.S.-Russian bilateral interactions, economic trends have not often coincided with the political fluctuations. As seen in Chart 1, an increase in U.S. imports from Russia took place when events occurred that affected the political area. Examples include the nationalization of Yukos (2003), the second war in Chechnya (1999-2009), and the color revolutions in Georgia (2003), Ukraine (2004), and Kyrgyzstan (2005). A decline in Russian oil supply to U.S. markets during a period of global financial turmoil (2008-2009) quickly reversed as soon as crude demand bounced, despite new political irritants in the bilateral agenda, particularly the Russia-Georgia war in August of 2008. After the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and a military conflict in eastern Ukraine, it seemed that bilateral relations were irreparably damaged, and economic cooperation under sanctions would come to naught. But surprisingly, an opposite trend of almost complete recovery in bilateral trade developed.

There are several reasons for this high resiliency in economic relations during chilly geopolitical environments: economic interactions are more inertial; interest groups and lobbying efforts play a role; U.S. consumption of Russian metals and oil, which make up about 80 percent of U.S. imports from Russia, have fallen under different forms of protections, where commercial pragmatism and economic interest overweigh political expediency. Moreover, Moscow prefers not to apply extremely destructive measures in bilateral trade because of the damage it would cause to the Russian economy.

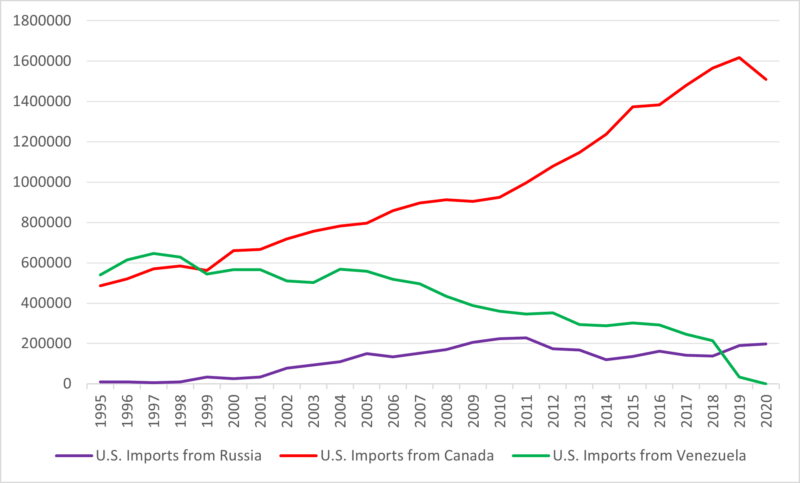

Some have argued that Russia’s heavy crude could be easily substituted by American shale production, but U.S. tight oil has replaced primarily light sweet crude from Africa and the Middle East. A heavy Russian blend has been attached to U.S. refineries since the early 2000s, as a result of technological innovation in the U.S. refining industry, the cost of which was about $100 billion. Many U.S. refineries are adapted to process heavy crude from Canada, Venezuela, and Russia. Chart 2 shows that a dramatic reduction in Venezuela’s crude production and the imposition of a U.S. oil embargo against Caracas has profited Canada and Russia by replacing Venezuelan heavy crude exports to the United States.

An asymmetric dependency in narrow sensitive areas and the relatively small value and volume of U.S.-Russian trade have limited the temptation and capacity of policymakers to use trade as a weapon in escalating geopolitical confrontations. Some sharp movements, such as Moscow’s countersanctions that nullified U.S. agricultural exports to Russia, reduced the trade balance by several hundred million dollars, an action that went unnoticed by the markets of both countries.

Overall, the existing bilateral trade model has a structural similarity to the model of U.S. trade with other developing countries, which centers around commodities—with the difference that Moscow has continued to exploit Soviet technological achievements and provided nuclear fuel for U.S. power plants and services to the U.S. airspace industry. However, the importance of these exceptional cases has eroded due to an increasing technological lag. Recently Elon Musk’s private company Space X has challenged Moscow’s monopoly on safe space launches, offering a U.S. domestic alternative to Russian rocket engines. Musk has started to launch satellites more cheaply and in larger quantities than Russia’s state corporation for space activities.

This creates a kind of deadlock, slowly melting a Soviet technological tradition that could almost completely disappear in the next five years if nothing replaces it. Furthermore, the second part of bilateral trade, Russia’s commodities delivery to the U.S. market, has also become unstable due to price fluctuations, tough competition, growing ecological pressure on the mining industries in their path to net zero, and an accelerated fourth energy transition which has radically reduced consumption of fossil fuels in the West. Beyond that, an inevitable contraction of Russian oil exports to the United States will occur as soon as Venezuela begins to recover from its protracted political and economic collapse.

Rate of Return vs. Politics

While U.S. exports to Russia are diversified, they have continued to stagnate, reflecting structural constraints in Russian economic and political development, a deteriorating investment climate, and the hardships of sanctions. Around 40 percent of U.S. exports comprise delivery of goods to roughly nine hundred U.S. companies operating in Russia today. Industries with a U.S. corporate presence there include energy and natural resources, IT and telecommunications, health care and pharmaceuticals, machine-building and chemicals, transports and logistics, construction and engineering, and financial and professional services. According to the American Chamber of Commerce, total direct investments by U.S. companies over the entire period of their operations in Russia amount to $85 billion, a figure that is six times higher than official numbers indicate.[1]

At the same time, the general quantity of U.S. corporate players in Russia is steadily decreasing, and the role of U.S. capital in the Russian stock market is shrinking. About 15 percent of the Russian economy is directly affected by sanction policies, but their non-direct outcomes on U.S. companies in Russia are much broader and include existing preferences for other country’s firms, growing reputational risks, and frozen contracts due to market contraction or disruption of supply chains. Ironically, not only did U.S. sanctions reduce the transfer of modern U.S. technologies to Russia, but Moscow itself chafes under technological dependence on the United States, especially in strategic sectors, trying to decrease it through economic diversification. In the process, Russia is also attempting to decouple from the global Internet, creating a “sovereign one” and hoping to insulate the country financially from a dollar influence.

During the last five years, Russia’s share of exports sold in U.S. currency fell from two-thirds to less than 50 percent, and Moscow’s U.S. treasury holdings have decreased from $105 billion to $3.9 billion. This has not been economically profitable and resulted in hundreds of millions in financial losses, while geopolitical concerns have prevailed. Just recently, following a decision to eliminate holdings in dollars from Russia’s National Wealth Fund, $40 billion was transferred overnight to alternative reserve currencies, mostly euro and yuan. Moscow has also declared its intention to gradually withdrawal from two major international payment systems—Visa and Mastercard.

All these moves have limited the possibility of economic modernization, worsened the country’s investment climate, and increased the cost of financial transactions. Despite that, the Kremlin has been ready to pay a heavy price to achieve its own strategic goal: obtaining a maximum degree of autonomy from the West. New technologies and geopolitical thorns have caused Russia to drift from a Western to a Chinese commercial, financial and technological platform following Beijing’s lead in the area of G5 networks, space exploration, e-commerce, modern transportation systems, retail, and tourism. There has also been a growing Russian exposure to Chinese investment and technology in the “holy of holies,” commodity extraction, and military buildup.

In the Russian realm of elite politics, pro-China lobbying groups have emerged that promote Moscow’s role as a strategic partner of Beijing and policies forming a “soft alliance” or “Pax Sinica” with China. The position of those in the Russian government and business community who would like to balance China’s increasing influence with European policy has weakened due to the open confrontation between Moscow and Brussels and a growing trend toward self-isolation, which is supported by Russian lawenforcement agencies.[2]

As it confronts the growing competition between Western and Chinese globalization models, the Kremlin’s anti-Western stance pushes it toward a “Pax Sinica.” There is at least one meaningful obstacle—most of Russia’s capital flows have continued heading to the West. Despite Putin’s policy of “elite nationalization,” increasing taxation of capital exports, and tightening offshore regulation, the West remains a magnet for wealthy Russians.

Conclusions

During the last 30 years, there have been non-synchronized political and economic cycles in U.S.-Russian relations. Relatively small official trade has been sustainable and resilient to deteriorating geopolitics and sanction policies, and its fluctuations have been mostly dependent on oil prices. The prospect of tougher Western sanctions and Russian authorities’ strengthening of anti-Western legislation and practices have continued to generate a dual structure of economic interaction: limited official trade and investments, and much more meaningful indirect turnover—trade through third countries and investments through offshore companies.

An archaic model of U.S.-Russian official trade makes almost inevitable its gradual decline in the next five to seven years. New economic ties could only emerge after Moscow begins deep structural reforms and modernization of its economic, legal, and political systems. Russia’s potential integration into China’s technological platform would substantially constrain future U.S.-Russian engagement. The dual structure of U.S.-Russian economic relations could be significantly reduced in the long run, in case of Russia’s complete integration into “Pax Sinica” or, alternatively, under conditions of the country’s significant economic liberalization.

Vadim Grishin is Adjunct Assistant Professor at George Washington University and Georgetown University.

APPENDIX

Chart 1. U.S.-Russian Trade ($ Millions) vs. Political Events, 1992-2020

Chart 2. U.S. Imports of Crude Oil and Petroleum Products from Russia, Canada, and Venezuela, Thousand Barrels, 1995-2020

[1] “Investments and Imports to Russia: Business in the Face of Uncertainty, 4th Annual Survey,” American Chamber of Commerce, Moscow, Russia, 2019, p.13.

[2] “Russia-U.S. Economic Cooperation Amidst Uncertainty,” Russian Council of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, March 2019 (in Russian).