For about a decade, negative, anti-Western, and anti-liberal ideological trends have been on the rise in Russia—corresponding to the Kremlin’s increasing reliance on such ideological and symbolic instruments to consolidate its legitimacy. As soon as Vladimir Putin embarked on his third presidential term, stances were radically hardened, and those who joined anti-Putin protests became branded in the eyes of the conservative majority as immoral and unpatriotic. Legislators have been adopting legal constraints on public expression, including freedom of assembly and freedom of speech. The government also sought to inculcate a more positive, patriotic, and ideologically correct mindset. Organizations that engaged in ideologically unwelcome activities have been cast as “foreign agents.”

The government has therefore been vastly expanding its operation in the realm of ideas, symbols, and historical memory. As Russian historian Alexey Miller pointed out in 2019, “State and state-aligned actors have come to dominate the scene of the politics of memory.” Two major organizations—the Russian Military Historical Society and the Russian Historical Society—were founded in 2012 under the Kremlin’s auspices. A multi-city exhibition called “Russia. My History” was launched with the central idea that most of Russia’s ills had come from the outside. Newly adopted “history laws” criminalized inappropriate interpretations of World War II. However, for all the Kremlin’s effort, its promoted conservatism is far from consensual. Discord is not limited to officialdom and the liberals that it steadily persecutes. Differences among Russian conservatives of various strains are often irreconcilable. The Kremlin’s engagement in this ideological realm has exacerbated differences, with a case in the fore being the return of the statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky to Lubyanka square.

Dzerzhinsky Revisited

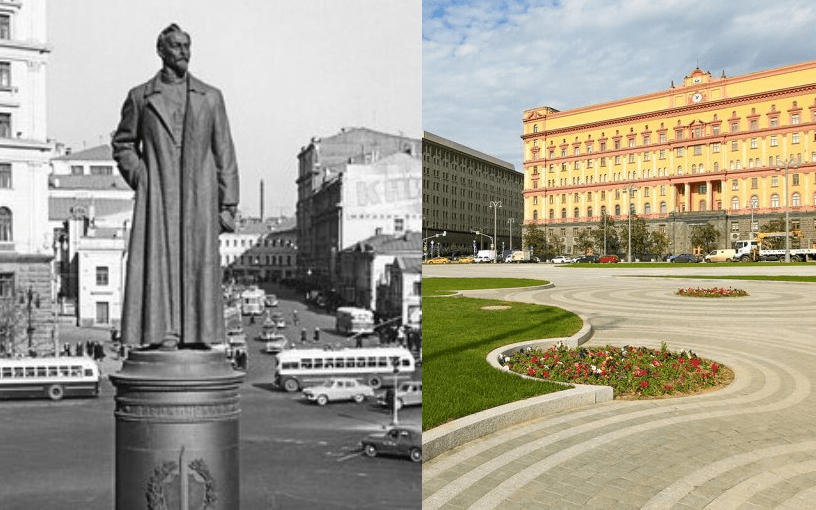

In early February, a group that included two authors, Zakhar Prilepin and Aleksandr Prokhanov, as well as a few others collectively described as “cultural figures,” called for the Russian government and the Moscow mayor’s office to bring the statue of Dzerzhinsky, the organizer of the Bolshevik Red Terror, back to Lubyanka square. The monument had been torn down by cheering crowds back in August 1991 as they celebrated their victory over the Communist putsch. The empty space in the center of the square is a symbolic reminder of the moment when the Russian people took action for the sake of what they believed was the right choice for their country.

Prilepin, most likely the major figure in the group of Dzerzhinsky exonerators, is one of Russia’s most famous contemporary authors and a very prominent public and political figure. He has published several novels; one of them, The Monastery, was a 2014 national best-seller and was translated into many languages. Currently in his mid-40s, in his youth, Prilepin used to be an active member of Eduard Limonov’s National-Bolshevik Party and a vocal opponent of Putin from left-wing nationalist positions. In 2014, however, after Russia annexed Crimea, Prilepin passionately supported Putin’s radical move and abandoned his anti-regime stance.

When the Crimea affair was followed by a war in Donbas, Prilepin became a zealous fighter—for a while, even an armed one—for the cause. He launched a fundraising campaign for the sake of Donbas residents and its armed militia, and in 2017 he founded the “Zakhar Prilepin Fund,” which has the goal of helping Donbas people in need. Prilepin is an unabashed nationalist, sometimes descending to xenophobia and antisemitism. In late 2019, he headed a new political party, “Za Pravdu” (“For Truth”), apparently upon the Kremlin’s authorization. His party took part in the September 2020 local elections, but its results were unimpressive: its candidates were able to win seats in just one regional legislature (Ryazan). Lately, Prilepin’s party merged with two others to form a “left-wing patriotic front” and will run for the national parliament in September 2021.

The Prilepin-Prokhanov group’s argument for returning Dzerzhinsky to his original location was not worded in straightforward Stalinist terms. Rather than explicitly exonerating Dzerzhinsky, a key figure in the early Bolshevik extermination of the “enemies of the revolution,” the group argued that the statue “had become part of Moscow’s historical and cultural landscape.” If they opted for this vague wording in order to make Dzerzhinsky’s return more palatable beyond hard-core Stalinists, subsequent developments showed their efforts were in vain.

Another reason cited by the Prilepin-Prokhanov group was that “the necessary national reconciliation cannot be understood as a revanche by one of the parties.” The implication thus being that the Solovetsky Stone erected in the same square back in 1990 to commemorate millions of victims of political repression needs to be balanced by a statue of their executioner. The Prilepin-Prokhanov associates’ affection for Dzerzhinsky is not unique; today’s siloviki establishment apparently also treats Dzerzhinsky as their glorious forefather.

Diverse Opponents to Dzerzhinsky’s Return

Initiatives bringing Dzerzhinsky back to his pedestal are hardly new. It was not surprising coming from Prokhanov and Prilepin, considering that they are known for their ultra-conservative politics. Each time the idea is raised, it is buried soon thereafter—arguably by Putin, who has not been in favor of radical demonstrations of rising Stalinists. This time was different, however, as the Prilepin-Prokhanov initiative to reinstate Dzerzhinsky was not buried but was followed by a flurry of events that involved prominent public figures. One of them, Ekho Moskvy’s irreplaceable leader, Aleksey Venediktov, claimed that the threat of a siloviki revanche had never been so grave, that the initiative to bring back Dzerzhinsky would be impossible to ignore, and that leaving the square as is, that is without a monumental centerpiece, was not an apparent option. The only way to prevent Dzerzhinsky’s comeback, Venediktov insisted, was to fill the Lubyanka vacancy with somebody else’s statue. But who?

The issue of the Dzerzhinsky statue has remained politically sensitive since 1991, and now it has predictably provoked an intense public debate in the media and on social networks. Alternative figures for a new Lubyanka statue have been promptly proposed, some from recent and others from old Russian history. A former minister of culture, Mikhail Shvydkoi, suggested the candidacy of Yuri Andropov, a long-term KGB chairman and a short-term Secretary General of the CPSU. Konstantin Malofeev, a businessman and prominent figure on the nationalist and religious fundamentalist front, nominated 15th-century Tsar Ivan III. Some proposed Alexander Nevsky, the 13th-century prince canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church. The Church itself explicitly criticized the idea of Dzerzhinsky’s return and also mentioned Nevsky as a possible candidate. Nevsky is well recognizable from school history courses. He is best known for his defeat of German crusaders and, therefore, fits well with today’s anti-western political environment.

Major Interference by the Moscow Mayor’s Office

Within days and without explanation, the mayor’s office single-handedly reduced the number of Dzerzhinsky “competitors” to just Nevsky, which conveniently coincided with this historical figure’s 800-year anniversary this year and planned celebrations. With inexplicable haste, the Moscow city authorities called an electronic popular vote to choose between Dzerzhinsky and Nevsky. Keeping the square empty—which would reaffirm, as it were, the symbol of the people’s 1991 victory over the Communist state—was thus declared as not an option. The authorities hinted (in a leak to the BBC) that they would prefer that Nevsky win the contest. Since manipulating public voting is common practice in Russia, Dzerzhinsky’s defeat seemed to be predetermined. The voting was supposed to have been open until March 5.

In a new twist, however, barely two days after the vote had started, Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin announced that the vote would be terminated. The count of the votes submitted so far, he informed, was only slightly in favor of Nevsky, leading the mayor to remark that such a split was “not good. Monuments in our streets and squares should unite society, not divide it.” But the return of Dzerzhinsky’s statue was well known to be a divisive issue. The whole chain of events raised questions. Why such a rush to call and then stop the vote? Were the Prilepin-Prokhanov group acting fully on their own, or are they connected to an actual “siloviki revanche”?

The Political Aspect

The drama suggests that in this case, as in so many others, what we are facing is the visible part of an otherwise hidden political clash between groups in and close to the establishment. One theory voiced by Dmitry Travin is that Dzerzhinsky’s return was originally Prilepin’s idea. The “tough and ugly” stance of Prilepin’s newly established party “Za Pravdu,” Travin says, is intended to attract those “who dream of a strong hand and are getting disappointed in the aging Putin.” Sobyanin then interfered (on his own or, maybe, with the Kremlin’s support) and effectively stopped Prilepin’s initiative. Sobyanin thus defeated Prilepin. End of the story.

This theory does not explain, however, whether Prilepin’s Kremlin patrons, who had given his party the go-ahead, were informed about his initiative in advance and what they think about his defeat. Travin portrays Sobyanin as a winner, but the Moscow mayor’s feverish moves—calling a vote, then promptly calling it off—makes him look anything but self-confident, rather, a bit ridiculous.

A more popular theory is that the whole Dzerzhinsky controversy was meant as a way to divert attention from Alexey Navalny, who had effectively undermined the Kremlin’s agenda: for over one month, the news has been dominated by his return from Germany, his arrest followed by mass protests and unprecedented police brutality, and his two trials. Even Putin’s state-of-the-nation address was postponed—apparently until Navalny has been securely silenced.

If diverting attention from Navalny was indeed the actual goal of the current Dzerzhinsky episode, then the Kremlin should be the main force behind it. (Some observers suggested in private that several other recent events, including Sergey Lavrov’s warning that Russia might break off its relations with the European Union, were also specially generated as a diversion). Indeed, the Dzerzhinsky controversy was a convenient diversion as it generated a heated public debate, and there was no longer a need for it after Navalny was transferred to a provincial penitentiary on February 26. Sobyanin called off the vote just a few hours after Navalny’s transfer on the same day. In this theory, Sobyanin does not look like his “own man” but like somebody taking orders from a superior, telling him when to call a vote and when to call it off.

Divisive passions have never been to the Kremlin’s liking, but the Dzerzhinsky controversy was a cost the Kremlin was willing to pay for diverting attention away from Navalny. Wrapping up the Dzerzhinsky debate turned out to be relatively easy: by closing the e-poll. But on other occasions, ideological passions, it turns out, are harder to pacify.

The Ideological Aspect

Whatever the hidden political underpinning of the current “Dzerzhinsky outbreak,” there is a genuine ideological aspect to it: some commentators have described the clash between Dzerzhinsky and Nevsky as a standoff between Stalinists and Orthodox Christians. Unlike such ideological groups, the general public may not care too much about historical memory issues, butwhen an ideological question is asked, public opinion appears to be split. The Dzerzhinsky discord is just one example.

In her study of Russia’s contemporary “ideological market,” Marlene Laruelle describes a broad range of highly vocal and active conservative “ideological entrepreneurs,” such as Stalinists and Soviet-style imperialists, religious fundamentalists, and monarchists. All of them may be described as conservative by virtue of sharing anti-liberal and anti-Western attitudes, but there are serious ideological divisions among them; they are often at loggerheads with each other and are not necessarily loyal to the Kremlin. While the Kremlin treats liberals as enemies, conservative entrepreneurs are seen as allies, at least against the West and domestic westernizers. Some of these entrepreneurs are difficult allies; they occasionally make trouble and are not easy to tame or dismiss.

As far back as 1999, Putin wrote in his “Millenium Manifesto” about the ideological divisions tearing Russian society apart and emphasized the need for reconciliation. He repeatedly returned to this topic in the following years. Even as late as 2012, he was talking about a “civil war” ongoing in the consciousness of many people.Early on, the Kremlin used to deal with ideological cleavages by marginalizing the divisive issues and keeping the official ideological lines intentionally blurred and uncertain. Apart from the glorification of victory in the Great Patriotic War, the Kremlin has hardly come up with a consistent narrative on any historical event, whether medieval, modern, or Soviet.

Putin himself sought to present Russian history as a mystical continuum, without breaks or ruptures. “Russia did not begin in 1917 or 1991,” he memorably said, “we have a common, continuous history spanning over one thousand years.” Since 2012, the state has deeply engaged in symbolic and historical politics. This change of policy has emboldened various ideological entrepreneurs who had, theretofore, kept a reasonably low profile; since then, their ideological clashes have repeatedly unfolded in plain sight.

One may recall an episode in which a Russian film about tsar Nicholas II’s well-known love affair infuriated religious fundamentalists who worship the last Russian monarch; when their demand to ban the film was turned down, they resorted to acts of violence and arson. An attempt to erect a Reconciliation statue that would commemorate the end of the Russian Civil War between “Reds” and “Whites” had to be abandoned after a group of “Red” sympathizers vehemently opposed that initiative. A couple of years ago, a scandal broke out during the construction of a gigantic Orthodox cathedral commissioned by the Ministry of Defense as a “main cathedral of the Armed Forces.” The Russian Orthodox Church authorities raised protests against the mosaics depicting Stalin that adorned the cathedral’s interior and demanded that they be removed. An Internet resource Russkaia Liniya (Russian Line), which describes itself as an “Orthodox news agency,” but characterized by observers as a mouthpiece of Stalinists, voiced an angry response to the official Church’s protest. Eventually, the Church prevailed, and the scandalous frescos were scraped off. These are but a couple out of many similar examples.

The conflict around the Dzerzhinsky statue has been hushed down, but the ideological and political causes behind it persist, and the issue of Dzerzhinsky’s return may reappear. On March 1, the Federation Council speaker Valentina Matvienko referred to the 1991 toppling of the Dzerzhinsky statue as an act of “vandalism” and suggested that the vote about a monument in Lubyanka be held again.

Conclusion

In 2014, Putin’s move to make Crimea Russian rallied the nation together. The “Crimean consensus” held for a few years but has now faded away. Society is no longer united. Pollsters have been pointing out that rifts are broadening. The Kremlin’s stepped-up engagement in the ideological and symbolic sphere is failing to bring the nation back together or to consolidate the regime’s legitimacy. The deep-seated divisions of active “ideological entrepreneurs,” as exemplified by the example of the Dzerzhinsky discord, prevents the Kremlin from formulating a definitive ideological line, let alone hammering it upon an ever-increasingly heterogeneous society.

The Russian people are not overly passionate about symbols. The only definitive and consensual narrative is that of the Great Patriotic war that has gradually evolved as a kind of “original myth.” Despite continuous government programs of patriotic education, post-Communist national holidays are not universally recognized. The state-sponsored organizations’ “monumental fever” resulted in hundreds of new statues of historical figures, but Russia still does not have consensual national heroes. In a 2017 Moscow poll, almost 40 percent had no idea about who deserves to be memorialized in stone. Even more telling for the future is that in a recent poll of 6,000 schoolchildren asking them to name their heroes, about a quarter of children could not think of a single heroic figure. A majority named their parents or grandparents, followed by movie and cartoon characters, and only a precious few named Russian historical figures.

Maria Lipman is an affiliate of the Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies (IERES) and the Program on New Approaches to Research and Security in Eurasia (PONARS Eurasia) at George Washington University.

Image credits: A. Васильев; Wikipedia (license)