Image credit/license

On October 22-24, 2024, Russian President Vladimir Putin hosted the latest BRICS summit in Kazan. Notably, it was the first gathering of the heads of state and government following last year’s expansion. As per the decision at last year’s summit, held in August in Johannesburg, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates officially became BRICS members on January 1, 2024. Although Argentina, under the new leadership elected in December 2023, declined the invitation to join, and Saudi Arabia chose to delay the confirmation of its accession, the near-doubling of BRICS members marked a notable international development. Against this backdrop, Russia seems to have emerged from its diplomatic isolation triggered by the Ukraine war. These optics, however, need to be contextualized.

High Diplomacy and Great Power Status

Special attention was bound to be given to promoting the Kazan summit as the high point of Russia’s BRICS chairmanship. Moscow sought to use it as a stage to showcase that it is, supposedly, fully back in the diplomatic limelight. Finding itself isolated diplomatically following its 2022 attack on Ukraine, the Kremlin proceeded to compensate for this by intensifying contacts and cooperation with non-Western great powers like China and India, other rising nations in Africa and the Middle East, and traditional allies in the post-Soviet region and by promoting non-Western fora like BRICS.

However, as I show below, notwithstanding the presence of a considerable number of foreign dignitaries in Kazan, it is premature to speak of a Russian diplomatic resurgence. A closer look at the guest list shows that they are mostly the nations that maintained significant contact with Russia—for strategic, pragmatic, or opportunistic reasons, or a combination of them—even after the West pressed to isolate and punish Moscow. Moreover, some came to Kazan not for Russia but rather to confirm their interest in joining BRICS and forge relations with its other members.

Russia’s emphasis on “high diplomacy,” which typically refers to state-to-state negotiations carried out by seasoned state representatives and top government officials, is central to its self-perception as a great power (for more on Russian diplomacy, see Charles E. Ziegler’s chapter in the 2018 edition of The Routledge Handbook of Russian Foreign Policy). Putin has actively practiced and visibly enjoyed summitry diplomacy with other world leaders, especially heads of powerful states. He seeks to validate his image abroad, assert Russia’s status as a great power, and cater to specific domestic audiences. Participation in such high diplomacy with the leaders of the world’s strongest and rapidly growing nations is linked to the question of status. Studies have shown that diplomatic contacts, summitry, and high-level state visits—among other traditional criteria, such as military power and a seat on the UN Security Council—are reliable indicators of a high-status perception of a given state (see “Status Considerations in International Politics and the Rise of Regional Powers” by Thomas J. Volgy, Renato Corbetta, J. Patrick Rhamey, Jr. , Ryan G. Baird, and Keith A. Grant, as well as “Status and World Order” by Deborah W. Larson, T.V. Paul, and W.C. Wohlforth in the 2014 edition of Status in World Politics).

Russian leaders have attached particular symbolic value to invitations to partake in exclusive gatherings of the world’s leading states, for instance, when Russia was first included in the G7 (which became the G8) in the mid-1990s. Conversely, when such invitations have been withdrawn—as was the case in 2014 following Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea—Russia has felt snubbed, despite downplaying the issue. It has sought to offset this by emphasizing the G20 and reengaging with regional non-Western blocs like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and associations like BRICS, among others. In 2014, the BRICS states took a common stance and opposed efforts by some Western governments (e.g., Australia) to exclude Putin from the G20 meetings. In addition, since the first conflict in Ukraine in 2014, Russia has increased bilateral interaction with successful emerging great powers like China to compensate for the downgraded relations with the West and Western efforts to isolate Russia.

Following the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russia experienced an even more dramatic hit to its status. At the United Nations, Moscow proved powerless to limit the damage from several rounds of General Assembly votes in 2022 that censured it for its military operations in Ukraine, a worsening humanitarian situation there, and its illegal annexation of Ukrainian territory, with nearly three-quarters of UN member states supporting these resolutions. Without providing any evidence, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov later accused Western powers, mainly the United States, of blackmailing many non-Western delegations in New York to vote for these resolutions.

In addition, Putin’s summitry with foreign leaders dwindled. In 2022, the Russian leader received far fewer foreign dignitaries—excluding Russia’s closest allies from the former USSR, along with a few foreign dignitaries who were trying to mediate between Moscow and Kyiv, like Naftali Bennett, the former Israeli prime minister—compared to before the pandemic. Indeed, except for former Soviet republics like Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, and Tajikistan, which are closely aligned and rely on good ties with Russia, and Moscow’s close international partners like China, a considerable number of others states, including those in the Global South that opted out of the Western sanctions regime, hesitated to continue regular interaction with Russia at the highest levels.

Even Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who had held one-on-one summits with Putin annually (except for 2020, because of the pandemic), neither invited Putin to India nor visited Moscow before July 2024. The two did meet on the sidelines of the September 2022 SCO summit in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, but an expected subsequent bilateral summit never materialized. Unconfirmed reports suggested that Modi sought to distance himself from Putin over the latter’s nuclear threats around Ukraine, although Indian government sources denied this speculation. In what some regarded as a desperate attempt to dispel the impression of his isolation and underscore uninterrupted ties with emerging great powers like India, Putin met with the visiting Indian foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, in December 2023 (note that Putin rarely receives foreign ministers).

Faced with such unprecedented international isolation, starting in mid-2022, Moscow reached out to non-Western states that did not follow Western-led efforts to isolate it. Especially in Africa, it tried to rekindle old ties with some states, including South Africa, Algeria, and Egypt, and made overtures to others like Mali, Uganda, and Sudan, where it provides mercenaries and weapons. It staged a second Russia-Africa Summit in July 2023. Nineteen heads of state and government attended, yet this was only half the almost 40 African leaders who had come to the inaugural summit in 2019; many participants in 2023 opted to send lower-level representatives instead. While Moscow was quick to accuse the West of pressuring African states not to participate in the summit, the reality is that they were still wary of being seen as freely interacting with Russia because of its stained reputation.

The 2024 BRICS Summit: Russia’s Diplomatic Rebound?

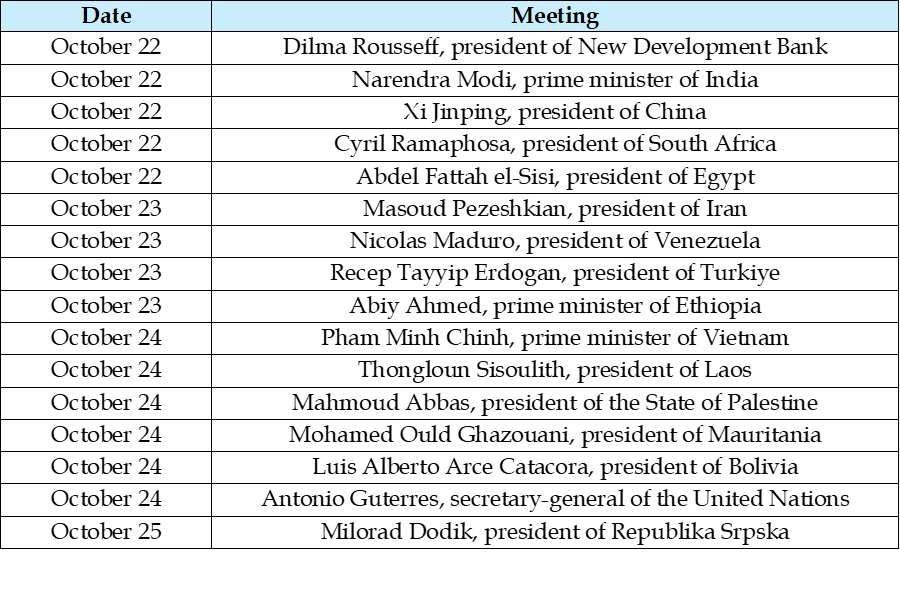

In the buildup to the Kazan summit, Russian Foreign Ministry officials hinted that the West and Ukraine were supposedly attempting to undermine the gathering, presumably by swaying state and international organization officials from attending. On October 24, following two days of meetings, Putin stated that delegations from 35 states and six international organizations participated in the summit, declaring it a “great success.” He met with numerous leaders, including UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres (see Table 1). In attendance was also UAE President Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, who met with Putin a day before the summit, and the leaders from Central Asian states and other former Soviet republics like Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Belarus, none of whom had individual meetings with Putin in Kazan (mostly because they regularly speak with him, for instance, at the annual CIS heads of state and government meeting in October). A notable absentee was Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, whose country is said to still be mulling over an official invitation to join BRICS.

Table 1. Putin’s meetings with foreign dignitaries in Kazan, October 22-25, 2024

Source: Kremlin.ru

In total, 24 heads of state and government attended the summit. While the symbolism of Russia hosting this many foreign leaders as it is embroiled in an illegal invasion of a neighboring state is significant, the fact is that Russia has been very close to, or at least has had good working relations with, most of these countries. Putin had developed personal connections with several of his guests in Kazan long before the summit: When the West pushed for sanctions and the isolation of Russia after the invasion of Ukraine, many of these leaders made the decision not to sever ties with Putin. They met with him openly at multilateral, regional fora or bilaterally, or both, and held regular phone conversations with him. Some states, like China and India, have, for strategic reasons, even elevated economic contacts with Russia (Beijing and New Dheli are now the main buyers of Russia’s discounted oil).

For instance, China’s President Xi Jinping met with Putin at the September 2022 SCO summit, visited him in Moscow in March 2023, had a meeting with him in Beijing during the October 2023 Belt and Road Forum, and hosted him for an official two-day state visit in May 2024. While Modi appeared cautious in openly promoting India’s historically friendly relations with Russia in 2022-2023, he nonetheless met with Putin on the sidelines of the SCO summit in September 2022 before paying a highly publicized (and criticized by some) state visit to Moscow in July 2024.

Other leaders, like Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, have frequently met and spoken with Putin over the years on various issues of interest to both countries, including the situation in Syria and Libya and bilateral trade deals. In response to the Ukraine war, Erdogan condemned Moscow’s actions but did not follow other NATO member states in imposing economic sanctions or isolating Russia. He met Putin four times in 2022 alone. He has sought to boost Turkiye’s diplomatic status by mediating between Kyiv and Moscow, in particular, facilitating the initiative to transport grain and foodstuffs from Ukraine’s Black Sea ports.

For his part, UN Secretary-General Guterres was in Moscow as early as April 2022 on a working trip to speak with Putin about the situation in Ukraine. While Ukraine criticized him for attending the BRICS summit in Kazan, the trip was not to pay homage to the Russian leader. According to the official UN news website (although, notably, not the official Kremlin site), Guterres reiterated to Putin that his country’s military operations in Ukraine violated international law and that the solution had to be a “just peace in line with the UN Charter, international law, and General Assembly resolutions.” Moreover, Guterres’ visit to Kazan was consistent with his previous presence at BRICS summits (e.g., the 2023 Johannesburg summit) and the recognition by the UN of the global importance of BRICS, as evidenced by the interest of many states in joining and cooperating with it.

Conclusion: Kazan Summit Delivers Limited Diplomatic Gains for the Kremlin

Overall, the presence of these and other leaders in Kazan hardly comes as a surprise and does not signal a marked improvement in Russia’s diplomatic posture. If anything, as a status-seeking great power, Russia should be expected to engage in high-level diplomatic activity and summitry. Meanwhile, it has been on a damage-control mission since it invaded Ukraine and was diplomatically sidestepped by many states.

The reality is that, more than two and a half years into the Ukraine war, Putin is restricted in his travel abroad by an arrest warrant issued for him by the International Criminal Court in March 2023. While Russia does not recognize the court’s jurisdiction, some of its BRICS partners do, and are obliged to arrest him. Putin had to skip the 2023 BRICS summit in South Africa because of this issue and has announced that he will miss another G20 meeting—scheduled for November 2024 in Brazil (he did not travel to the G20 meeting in Indonesia in 2022)—supposedly so as not to undermine and disrupt “the routine work of this forum.”

This highlights Russia’s inability to fully compensate for its lost membership in Western-led fora with non-Western ones and effectively maintain its previous high diplomatic visibility. Despite his repeated claims about the declining influence and importance of the “collective West,” Putin does not deny its relevance or even his desire to mend the broken ties. When asked at the Kazan summit whether he missed engaging with his Western counterparts, he replied that Russia had never refused contact and dialogue or ruled out a restoration of relations with the West.

What the presence of so many delegations in Kazan underscores is the growing global allure of BRICS, with outsiders showing continued interest in cooperating with its members, not just Russia. Other states that were represented at the summit sought to affirm their already-expressed interest in joining the association in the near future. Their interest—Turkiye is but one example—is driven by the opportunity to solidify ties with global economic superpower China and a rapidly growing India and attract more investment from them. While Russia as a host played its part in providing an agreeable venue for the multilateral meetings, the heralding of the recent BRICS summit as Russia’s return to the grand diplomatic stage is premature and misses the many challenges that Moscow still faces to restore the status it enjoyed before February 24, 2022.

[1] Dr. Janko Šćepanović is an assistant professor of international politics at the Shanghai Academy of Global Governance and Area Studies (SAGGAS) of the Shanghai International Studies University. His research focuses on international relations theory, especially the role of status, as well as the empirical study of Russia’s foreign policy in the post-Soviet region, the Middle East, and Southeast Europe and regional institution-building in the post-Soviet region.Image credit/license