(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) With or without Russian intervention, Ukraine was going to face a difficult road after the Euromaidan revolution. Strikingly, much of the current Western economic aid and advice seems no different from admonitions before the war or, indeed, during the last two decades. Advisers appear to believe that today’s era of “extraordinary politics” will produce different results than the one of the early 1990s. But while the government has moved further and faster on some macroeconomic policies than might have been expected—aided by forces beyond its control—the longer-term changes that are more important to most Ukrainians are far less amenable to the cudgel of “political will.” Additional steps forward will require a better understanding of how other countries have mitigated the destructiveness of corruption and oligarchic activity.

The History and (Slight) Evolution of IMF Loan Packages and Requirements

After the end of the Soviet Union, Ukrainian growth was sluggish at best, and the federal budget was in chronic deficit. More frustrating to the general population, oligarchs dominated both economics and politics, and corruption seemed ubiquitous.

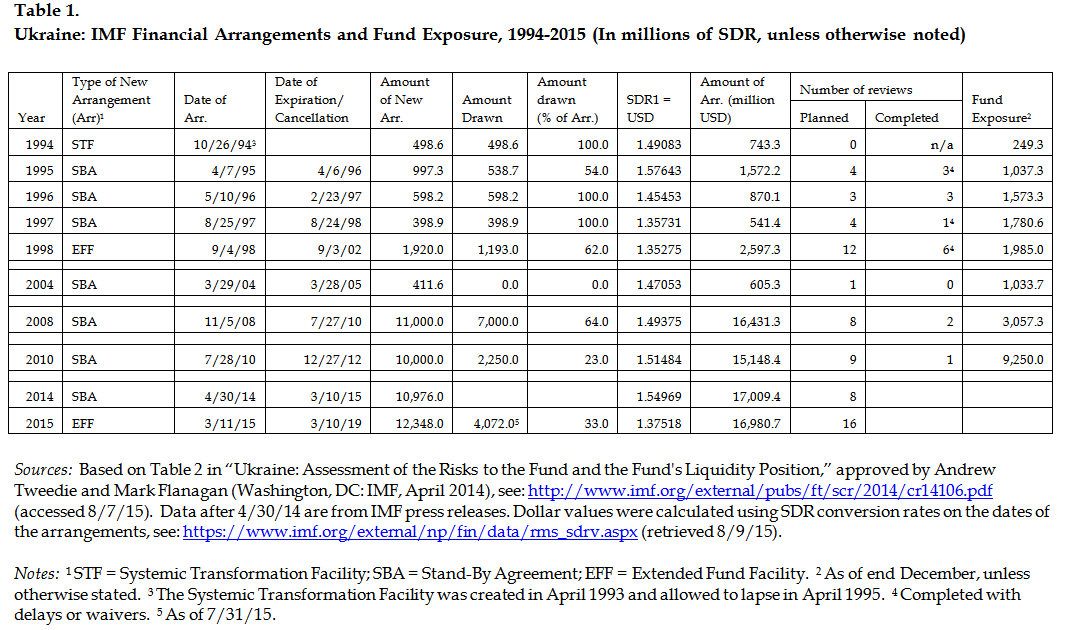

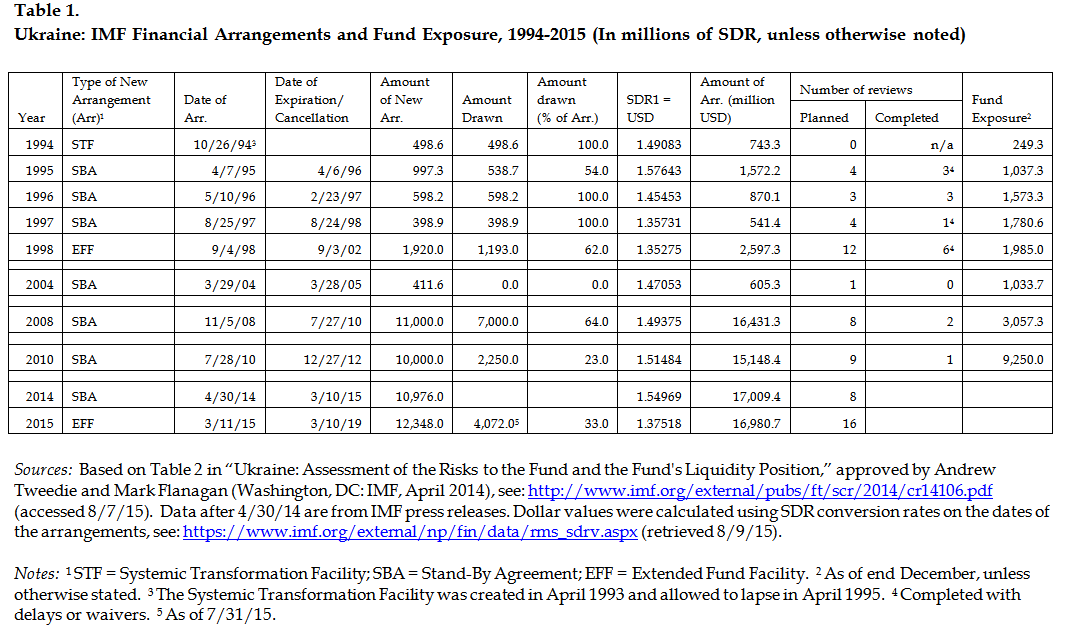

The conflict in eastern Ukraine exacerbated these problems, but the war also brought renewed emphasis on Western economic aid and advice. Ukraine signed deals with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2014 and 2015. These agreements, however, were hardly the first of their kind. Ukraine joined the IMF in 1992 and signed agreements annually from 1994 to 1998, and then again in 2004, 2008, and 2010. For the first decade and a half, the agreements were relatively small; most were under a billion dollars, one was $1.5 billion, and the 1998 agreement was for $2.5 billion to be disbursed over three years. The global financial crisis of 2008 radically changed the stakes of the game, and the Fund agreed to an arrangement of almost $16.5 billion. The agreements of 2010, 2014, and 2015 have been of a similar size, though of different durations (see Table 1). A consistent theme of these deals has been disappointment on the part of the IMF. Each new arrangement includes praise for the government’s renewed commitment to the policy requirements attached to the loans, but the polite language of failure is also usually present. For example:

- “delays and slippages in policy implementation occurred during the second half of 1995”

- “domestic consensus could not be reached on several key elements of the [1996] program”

- “overall performance under the [1997] program was less than aimed for”

- “[There have been] difficulties in implementing key structural reforms [in the 1998-2001 program]”

- “the [2008] program eventually went off track as policies weakened and reforms stalled in the run up to the Presidential elections”

(Source: www.imf.org)

In addition to the rhetoric of disillusionment, the IMF was often unable to complete all its planned reviews of the programs. About half the time it did not disburse all the promised funds, withholding them for lack of compliance.

Throughout this period, the conditions attached to the loans have remained remarkably stable. While the emphasis varied, requirements could always be placed under the three headings of liberalization, stabilization, and structural reform. Liberalization meant free prices, more open trade, and a unified, free-floating exchange rate, with the exchange rate receiving the most consistent emphasis. Stabilization meant lower inflation and a more stable exchange rate, each being achieved by tightening fiscal and monetary policy; regardless of the size of the deficit or the money supply at the time, the plan recommended reducing them. Each agreement also included mollifying language about protection of the “most vulnerable,” although details were often sparse and focused on ascertaining whether the supposedly vulnerable were actually vulnerable.

“Structural reforms” was a broad category that shifted more than the others from plan to plan. In the early years, privatization was emphasized, but that faded by the end of the 1990s. Several of the plans referred to increased budgetary transparency and oversight, as well as improved tax administration. Another frequent focus was improving the “business climate,” which usually meant deregulation, sometimes along with demonopolization. The structural reforms that received the greatest emphasis in the most recent agreements were banking reform (including recapitalization and improved banking supervision), restructuring of the energy sector (especially improved transparency at Naftogaz and increased domestic prices for natural gas), and anti-corruption efforts. In all the plans, structural reforms were listed last and addressed more cursorily than fiscal and monetary policies.

The Political Context of Economic Reform in Today’s Ukraine

Is there any reason to expect that the same program that could never be implemented in the past will be implemented now? The IMF’s newfound sense of optimism relies on changes since February 2014 in Ukraine’s political context, in particular, popular support among the population and “political will” among politicians. The idea is that we have entered a new, more auspicious, period of “extraordinary politics” in which formerly impossible legislative and administrative feats can be achieved.

Popular support in the majority of the country that Kyiv can effectively govern is indeed likely to be stronger than in the past. The rally-round-the-flag effect produced by the war can be expected to buy the government considerable leeway in carrying out new policies, and the energy that produced the Euromaidan revolution can certainly be seen as “pro-reform.”

It is crucial, however, to recognize the “reforms” the population is likely to support are of a particular type. Broadly speaking, Ukrainians want government officials to be less corrupt, oligarchs to be less powerful, Naftogaz to be more transparent, courts to be more honest, and rank-and-file citizens to be better off. People did not stand on the Maidan clamoring for higher natural gas prices, lower pensions, and higher interest rates. It is possible they will swallow some austerity policies in the near term, but their main interest is in making the system fairer (as they understand the term).

It is likewise possible that politicians’ “political will” is significantly greater now than before the war (and if the population’s resistance is reduced, it may not take as much gumption to force them to tolerate reduced subsidies and higher taxes). At the very least, parliament is not as divided as it was before over the question of whether to try and join the European or Russian sphere. Here too, however, we should not overemphasize the change. Politicians in any setting are actors with multiple interests. Their desire for reelection, their need to provide favors to economic supporters, and sometimes their willingness to engage in corruption can all divert them from pursuing policies that can cause pain among any of their constituencies. And the Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk's government may be on the verge of collapse, although the likelihood of a strongly anti-IMF government replacing it seems low.

Meanwhile, the forces that mitigate against implementing the IMF’s conditions are significant. Chief among them is the Donbas conflict, which has powerful fiscal and monetary implications. Paying for the war directly counters efforts to reduce the budget deficit, while collecting taxes in Crimea and the Donbas is either difficult or impossible. On the monetary side, government spending, economic decline, and political uncertainty all undermine the hryvnia. The formal ceasefire mitigates some of these problems, but low-level conflict continues, and the threat of renewed open hostilities remains.

Even without the war, the Ukrainian government would face enormous challenges to its ability to govern and therefore to pursue new political and economic policies. Crucially, the level of oligarchic influence in Ukraine, economically and politically, remains enormous. No government before the Euromaidan was able to bring them under control, despite several efforts over the past two decades. Furthermore, deep divisions within the population—between east and west, industrial and agricultural sectors, liberals and nationalists—would need to be addressed with or without the conflict.

However, the conflict has tempered some of the country’s differences, both because Crimea and the easternmost regions have effectively been cut out of Kyiv politics for now and because the remaining population has been forced to look west for support. But those conflicts will return if Kyiv is able to restore control over its breakaway regions. More immediately, the liberal-nationalist split is real, and while the parliamentary elections showed weak support for the nationalist side, militia groups on the right that played a role in the success of the Euromaidan continue to contribute to the war effort and came into direct conflict with government forces earlier this year. These factors hamper Kyiv’s ability to govern its own territory and to pass and implement policies that challenge vested interests in society.

An Interim Scorecard: Precarious Progress toward a Limited Goal

In this extraordinarily difficult set of circumstances, Ukraine has seen some surprising successes on the reforms’ own terms. Inflation declined rapidly in the second quarter of 2015; according to the Economic Intelligence Unit (EIU Europe), the monthly inflation rate was about 14 percent in April, two percent in May, zero percent in June, and negative one percent in July. Similarly, the hryvnia reached its nadir against the U.S. dollar in late April (at over 30 to the dollar) and has since fluctuated in the neighborhood of 20-22 to the dollar. Supporting these outcomes was a large hike in interest rates, which reached 30 percent in March 2015. At the same time, the decline of GDP slowed dramatically: the economy shrank more than five percent in the first quarter of 2015 but only 0.9 percent in the second. These surprising developments prompted IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde in a July 2015 press briefing to describe the situation as “incredibly encouraging…notwithstanding the very difficult security and military situation [in the east].” The IMF downgraded its 2015 growth expectations in October, but it repeated that “the exchange rate has been broadly stable, hryvnia deposits are rising, and inflation is receding.” It predicted two percent growth for 2016.

In addition to these quantitative successes on macroeconomic issues, the government has reported progress on the types of structural changes in which the population is most interested. Oligarchs Dmytro Firtash and Ihor Kolomoisky have both been challenged, with the United States trying (but failing) to extradite Firtash from Austria and the Ukrainian government weakening Kolomoisky’s influence at UkrTransNafta, despite the his dispatching armed men to the company’s headquarters.

Concurrently, the government began to purge and replace the ranks of the police force, with new recruits trained with the assistance of the United States and Canada in an effort to create a new organization without the taint of past corruption. An additional strategy—which has not gone without criticism—has been to bring in (former) citizens of other countries to lead important agencies or regions, including U.S.-born Natalie Jaresko to head the Ministry of Finance, Lithuanian Aivaras Abromavicius as Minister of Economy and Trade, and both Georgian Mikheil Saakashvili and Russian Maria Gaidar to provide leadership in the Odessa region. Among the greatest successes of this policy was Jaresko’s major restructuring of the country’s external public debt in August 2015, reducing the principal and lengthening the repayment schedule.

At the same time, enormous problems remain. In terms of macroeconomic numbers, the country continues to live under a sword of Damocles. As of the start of December 2015, the government still had not submitted a 2016 budget that met IMF goals of “further reduc[ing] the budget deficit and the public debt to saver levels.” External private debt remains high, and mortgages denominated in foreign currency threaten to either swamp Ukrainian homeowners or pit Ukraine against private international banks. The hryvnia, inflation, and the budget are all susceptible to shocks related to the war. Russia still controls levers that affect Ukraine’s economy, including a $3 billion Eurobond and a recent decision to suspend free trade with Ukraine from January 2016. Reports of corruption scandals still permeate the media, and a study released by Transparency International in August 2015 shows many citizens do not believe corruption has diminished since the Euromaidan. Furthermore, oligarchs remain, and the arrests and prosecutions that have occurred may be more about settling political scores than creating a level playing field in the economic realm.

From the perspective of the IMF, the Ukrainian government has achieved more than might reasonably have been expected over the past year and a half. Celebrations, however, should be tempered for two main reasons. First, the macroeconomic achievements are precarious and have been possible partly because of fortuitous external conditions, especially low world energy and commodity prices, rather than the actions of the government. Second, the deeper challenges of changing how Ukraine’s political economy functions are far more difficult to overcome. The history of economic development does not provide clear instructions for eliminating corruption and oligarchic influence. At best, it shows countries that have incorporated such phenomena into a system that also provides significant benefits to the rest of society. Ukraine’s evolution over the next several years may provide another window on that process.

Andrew Barnes is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Political Science at Kent State University.

[PDF]