(PONARS Policy Memo) In a 1987 speech in Murmansk, Mikhail Gorbachev famously called for the Arctic to become a “zone of peace.” Since the end of the Cold War, Arctic states largely succeeded in insulating the Far North from tensions in great power relations. However, the crisis between Russia and the West since the onset of the conflict in Ukraine in 2014 threatens to disturb the Arctic peace at a time when cooperation is all the more urgent due to growing challenges to the region from climate change.

Among Arctic states and in northern Europe more generally, fear of Russian aggression has overtaken earlier concerns about a race for Arctic resources. Despite eye-catching stunts in recent years like the annual landings since 2014 of Russian paratroopers on the ice near the North Pole, the increasing concern about Russian intentions has little to do with Russian territorial claims in the Arctic; rather, the overlap between Arctic and Baltic military deployments by Russia and NATO alike threatens to conflate Arctic and Baltic security concerns. But the spillover of security problems on NATO’s peripheries to the Arctic will do little to resolve the region’s real issues, which are primarily environmental threats and human security, particularly to indigenous communities. What is needed in the Arctic is a confidence-building mechanism that will ensure that out-of-area issues do not erode two decades of cooperative interactions. NATO also needs to articulate a clear position on Arctic security so as to avoid carrying over tensions with Russia in the Baltics to the Arctic.

Russia’s Arctic Ambitions

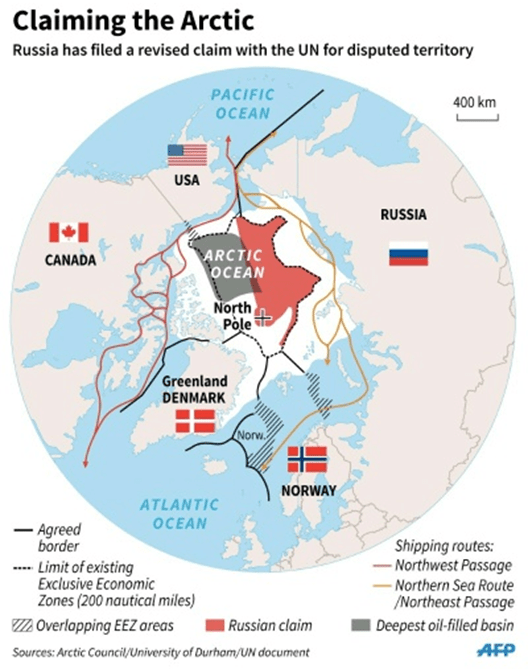

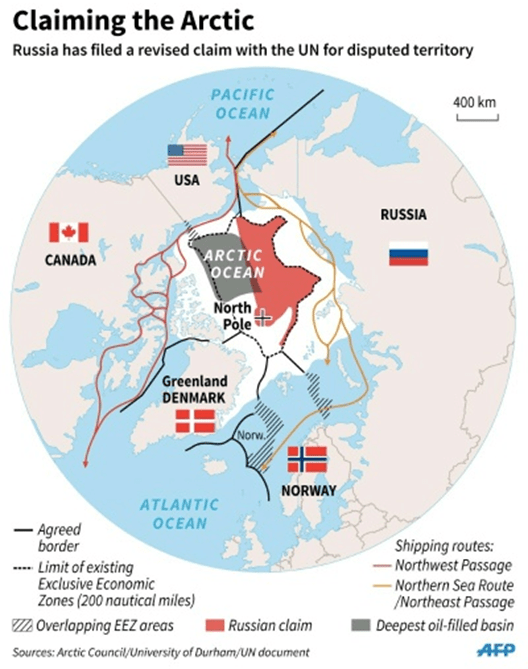

There is no question that Russia considers the development of the Arctic as a strategic priority. Russian President Vladimir Putin stated in 2014 that the Arctic represents “a concentration of practically all aspects of national security—military, political, economic, technological, environmental, and that of resources.” Russia is the largest polar state, with an Arctic coastline of more than 4,000 miles. Much of Russia’s energy and mineral wealth lies untapped in its Arctic regions. The acceleration of climate change has opened the possibility of commercial shipping along the Northern Sea Route, over which Russia claims sovereignty. After a Russian submarine crew dramatically planted a flag on the Arctic seabed in 2007, doubts first arose about Russia’s intentions in the region. More recently, in February 2016, the Russian government revised its claim to the United Nations to 1.2 million square kilometers of the Arctic seabed, including the shelf beneath the North Pole.[1]

In the past decade, Russia has issued a series of strategy documents about the Arctic and explained how the region fits in its military and maritime doctrines. In recent years, Russia also has been highlighting its Arctic ambitions by establishing a new Arctic Command, building up its Arctic forces, developing new bases in the region, reopening Soviet era installations, conducting military exercises, and engaging in frequent submarine patrols in the region.

Some Western observers warn of Russia’s quest for supremacy in the Arctic and urge the U.S. government to close the “icebreaker gap.” Although it is true that Russia has a ten to one advantage in this area—about forty operational icebreakers compared to four for the United States—it also has a much more extensive Arctic coastline to service. Moreover, as a result of oil and gas development in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug where 90 percent of Russia’s energy resources are located, the population there has grown to 530,000 in 2016, despite population decline elsewhere in the Russian Arctic. By comparison, there are just 27,827 people in Alaska’s Northern Economic Region. Despite Russian superior icebreaker capability, other experts point to the inadequate infrastructure in the Russian Arctic and constraints on access to needed financing given the low price of oil and economic sanctions. This has raised questions about the purpose of Russia’s Arctic ambitions.

Is Russia’s Arctic policy today more about symbolism than substance?[2] Valery Konyshev and Alexander Sergunin contend that Russia’s Arctic policy today is much different from the Cold War era of global confrontation and is focused instead on demonstrating Russian status as a great power, protecting its economic interests in the Far North, and safeguarding what is claimed as the Russian exclusive economic zone. Nonetheless, they acknowledge that Russian policy is both assertive in promoting sovereignty claims, inward-looking in acknowledging that Russia’s Arctic role will depend on the resolution of domestic economic problems, and seeking soft power through international cooperation.

How is NATO in the Equation?

Although the July 2016 NATO summit did not mention the Arctic specifically, the final communiqué spoke of “an arc of instability along NATO’s periphery and beyond” and noted that:

“Russia’s aggressive actions, including provocative military activities in the periphery of NATO territory, and its demonstrated willingness to attain political goals by the threat and use of force, are a source of regional instability, fundamentally challenge the Alliance, have damaged Euro-Atlantic security, and threaten our long-standing goal of a Europe whole, free, and at peace.”

Five out of seven members of the Arctic Council, the primary governance forum for the region—the United States, Canada, Iceland, Denmark, and Norway—are also NATO members. Finland and Sweden, members of the Arctic Council but not of NATO, have increased their level of cooperation with the Alliance in response to provocative Russian military exercises near their territory since 2014 and have been reexamining their security posture, including their relationship with NATO.

Before the Russian intervention in Ukraine, NATO was opposed to building up military capabilities in the Arctic and encouraged regional cooperation. In the current political climate, however, the perception of an increased Russian threat to the region provides a rationale for enhancing military preparedness in the High North. In March 2016, the Arctic Ice Exercise (ICEX) led by the U.S. Navy with the participation of British, Canadian, and Norwegian forces served to reassure NATO allies, particularly in the Baltics. While the exercise was scheduled prior to the Russian takeover of Crimea, and the Navy denied it was planned with Russia in mind, maneuvers included a simulated torpedo firing against a simulated Akula class Russian sub.

Russian analysts contend that their country’s naval and air forces in the Arctic are inferior to NATO forces and claim that Russia has actually scaled back its Arctic military presence compared to the Soviet era. A classic security dilemma appears to be unfolding, in that Russia interprets the actions the United States and NATO have taken to enhance their own security in the Arctic as threatening, leading to an expansion of military capabilities, which make the United States and its allies even more alarmed. Even prior to the conflict in Ukraine, Russian officials criticized what they viewed as NATO’s militarization of the Artic. The appointment of Dmitry Rogozin, Russia’s former representative to the NATO-Russia Council and a critic of the organization, to head the Russian Presidential Commission on the Arctic established in 2015, only serves to further blur the boundaries between Russia’s relations with NATO and its Arctic security concerns.

Post-Cold War Scientific Cooperation in the Arctic

Meanwhile, far from international scrutiny, US-Russia scientific cooperation in the Arctic continues to move forward. In the final years of the Cold War period, a desire for scientific collaboration and environmental protection in the Arctic led to initiatives which culminated in the creation of the Arctic Council in 1996. The intergovernmental forum’s founding agreement, the Ottawa Declaration, specifically omits security issues from the Arctic Council’s purview in an effort to focus on environmental, scientific, and economic cooperation priorities. U.S. and Russian scientists have been cooperating in this area both within the framework of the Arctic Council and outside it for many years and continue to do so despite political tensions. Joint efforts include:

· Preventing unregulated fishing in the high seas through expert meetings that the United States hopes will culminate in a binding treaty.

· Environmental monitoring at the Tiksi International Hydrometeorological Observatory in Russia’s Sakha Republic, a joint effort by the United States, Russia, and Finland.

· Collaboration with Russia’s Northeast Science Station in Chersky in the Sakha Republic, which regularly hosts foreign scientists and student exchanges through the Polaris Project, an initiative launched by the Woods Hole Research Center in the United States in 2008.

· Joint oceanographic research through the Distributed Biological Observatory, a joint effort by the United States, Russia, China, Japan, South Korea, and Canada to pool data from measurements obtained near the Bering Strait.

· Joint U.S.-Russian efforts to track fish life in the Chukchi Sea through the Russian-American Long-Term Census of the Arctic.

One week after the July 2016 NATO summit in Warsaw highlighted East-West tensions, the Arctic Council Scientific Task force succeeded in reaching a binding agreement on scientific cooperation—only the third binding treaty ever reached by the Arctic Council since its formation in 1996—that will be signed at the next ministerial meeting of the Arctic Council, in Fairbanks, Alaska in May 2017. The United States, Russia, and Sweden co-chair the Scientific Task Force of the Arctic Council, created in March 2013 to enhance scientific cooperation among Arctic states.

Despite these achievements, U.S.-Russian tensions over the conflict in Ukraine have been felt as far away as the Arctic. Funding for some joint Arctic programs was cancelled after the Russian takeover of Crimea. For example, the State Department refused to fund a US-Russia conference on natural disasters scheduled to take place in Alaska in 2014. Russian representatives were denied visas to two experts meetings in Canada in 2014 to set up an Arctic Coast Guard forum. Moreover, Putin’s restrictions on the activities of U.S. foundations and NGOs in Russia have complicated cooperative efforts between international and Russian NGOs. In 2015, however, Russia was one of the eight Arctic countries participating in the 2015 founding meeting of the Arctic Coast Guard Forum and Russia continues to cooperate with U.S. (and Norwegian) coast guards.

Avoiding Arctic Security Dilemmas

Recognizing the potential for security dilemmas to increase, U.S. officials involved in Arctic affairs have sought to insulate the region from current tensions in US-Russia relations. In testimony to Congress in November 2015, Admiral Robert J. Papp, then the U.S. Special Representative for the Arctic, urged policymakers to put current tensions with Russia in a broader context and called attention to the longer record of cooperation between the United States and other countries with Russia in the Arctic. A 2015 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office noted that the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) saw a low level of threat in the Arctic and found regional states largely willing to cooperate. Consequently, the DOD saw its role as largely supportive of the missions of other agencies, such as the Coast Guard’s role in Search and Rescue. In fact, the 2013 DOD Arctic strategy specifically warned against a militarization of disputes over fishing rights or sovereignty issues in the Arctic, lest it lead to arms races and undermine regional cooperation. Nonetheless, recent US-Russia tensions in the Arctic have provided support for an expansion of U.S. Arctic capabilities, including the commissioning of a new nuclear icebreaker and upgrading the U.S. Navy aircraft hangar at the Keflavik base in Iceland, as well as justifying a reprieve for expected cuts in the only cold weather brigade in the U.S. Army.

Because the Arctic Council is prohibited from discussing international security issues, this task has fallen to European security institutions, such as the Arctic Security Forces Roundtable (co-hosted by the United States and Norway) and the Northern Chiefs of Defense conference. However, the latter has not met for three years due to Russian actions in Ukraine and Russia has not been attending the former. Some analysts have called for a formal NATO role in the Artic and the development of a NATO Arctic strategy, but this will only generate NATO-Russian Arctic tensions instead of addressing the region’s concerns. What is needed instead is an Arctic framework for discussing security issues and regional confidence-building initiatives.

Other experts have suggested broadening the focus of the Arctic Council to accommodate such discussions. A new organization could also be created with a broader-based membership, including observer states that would be non-NATO states. This could be modeled on the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), which brings together ASEAN states plus interested great powers and other states outside the region. Although Russia participates in the ARF, it is unlikely to support a new broader framework for the discussion of Arctic issues. For example, Russian officials have been cool to expanding the ranks of observer states in the Arctic Council, putting the European Union’s bid on hold.

Confidence-building measures also could be elaborated multilaterally or bilaterally and address issues such as advance notification of military deployments or restrictions on military movements in particular areas. In a 2016 report for the Russian International Affairs Council, for example, MGIMO Professor Andrei Zagorski called for Track II discussions on Arctic security issues to improve transparency at a time when most military-to-military dialogues have been suspended between the United States and Russia.

Elizabeth Wishnick is Professor of Political Science and Law at Montclair State University and Senior Research Scholar at the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University.

[PDF]

[1] See: Sergei Medvedev, “The Kremlin’s Arctic Plans: More Gutted than Grand,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 430, June 2016.

[2] See: Marlene Laruelle, Russia’s Arctic Strategies and the Future of the Far North (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe), 2014.