PONARS Eurasia Task Force: Russia in a Changing Climate

As the climate emergency escalates, we have seen an accompanying growth in research on climate change in the social sciences. Russia is the largest country on the planet and a key producer of fossil fuels, yet minimally represented in this expanding research. Much remains to be done to understand both the processes and politics of responses to a changing climate in a country so central to planetary health. The effects of Russia’s war against Ukraine, Western sanctions, and the resulting uncertainty in international efforts to address climate change also require deeper understanding.

The aim of the PONARS Task Force on Russia in a Changing Climate is to address this lack of evidence-based research by convening a group of scholars with expertise in different aspects of politics and policy in Russia. The group will work to encourage the production of both basic research and policy-oriented contributions by offering a forum for discussion, coordination, collaboration, and dissemination. Collective contributions, as well as individual and small group products, will be promoted. The Task Force will also seek to support research by networking scholars of Russia with each other and with climate experts and by assisting scholars in identifying and accessing sources of funding for research related to Russia in a Changing Climate.

Members

Task Force Reports

Russia in a Changing Climate, Wires Climate Change

By Debrah Javeline, Robert Orttung, Graeme Robertson, Richard Arnold, Andrew Barnes, Laura A. Henry, Edward Holland, Mariya Omelicheva, Peter Rutland, Edward Schatz, Caress Schenk, Andrei Semenov, Valerie Sperling, Lisa McIntosh Sundstrom, Mikhail Troitskiy, Judyth Twigg, and Susanne Wengle

December 2023

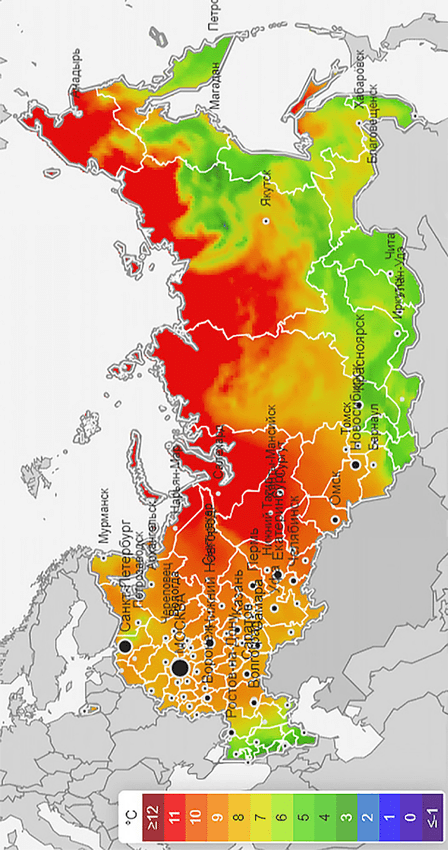

Climate change will shape the future of Russia, and vice versa, regardless of who rules in the Kremlin. The world’s largest country is warming faster than Earth as a whole, occupies more than half the Arctic Ocean coastline, and is waging a carbon-intensive war while increasingly isolated from the international community and its efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Officially, the Russian government argues that, as a major exporter of hydrocarbons, Russia benefits from maintaining global reliance on fossil fuels and from climate change itself, because warming may increase the extent and quality of its arable land, open a new year-round Arctic sea route, and make its harsh climate more livable. Drawing on the collective expertise of a large group of Russia-focused social scientists and a comprehensive literature review, we challenge this narrative. We find that Russia suffers from a variety of impacts due to climate change and is poorly prepared to adapt to these impacts. The literature review reveals that the fates of Russia’s hydrocarbon-dependent economy, centralized political system, and climate-impacted population are intertwined and that research is needed on this evolving interrelationship, as global temperatures rise and the international economy decarbonizes in response.

Recommended Reading

The UNFCCC: Climates for NGO Mediation in China and Russia (Oxford Academic, 2021)

By Laura A. Henry and Lisa McIntosh Sundstrom | Russian NGOs and Chinese CSOs working to address climate change have exhibited different levels of participation as observer organizations at the annual UNFCCC COP meetings. In recent years, participation by Chinese CSOs has grown dramatically, while that of Russian NGOs has stagnated. This chapter investigates and explains that variation and what it tells us about challenges for NGO mediation. It highlights the distinct qualities of state-society relations in Russia (more confrontational) and China (more co-optational), even though both regimes are authoritarian, and differences in policymaking context given the Chinese government’s active interest in climate policy and the Russian government’s more limited efforts. These factors paradoxically allow NGOs in China’s one-party state more opportunities to engage with the UNFCCC and influence the domestic climate policy agenda; despite Russia’s “competitive authoritarian” regime with multiparty elections, NGOs there face a largely hostile and exclusionary context for climate policy.

Climate change in Northern Russia through the prism of public perception (Springer, 2018)

By Oleg Anisimov and Robert Orttung | This article fills a major hole in the Western literature on climate change perceptions by reporting detailed data from Russia. While Northern Russia demonstrates high rates of climate change, regional adaptation policies are yet to be established. Complicating the problem, how the Russian public perceives climate change remains poorly known. This study synthesizes data from observations, modeling, and sociological surveys, and gives insight into the public perceptions of current and projected future changes in climate. Results indicate that, similar to what is found in the Western context, unusual weather patterns and single extreme events have a deeper impact than long-term climate change on public perceptions. The majority of the population considers climate and environmental changes locally, does not associate them with global drivers, and is not prepared to act on them. Accordingly, even the best designed climate policies cannot be implemented in Northern Russia, because there is no public demand for them. To address this situation, climate scientists should work to educate members of the public about basic scientific concepts so that they begin to demand better climate policies.

By Debra Javeline | Few, if any, political scientists currently study climate change adaptation or are even aware that there is a large and growing interdisciplinary field of study devoted not just to mitigating greenhouse gas emissions but to reducing our vulnerability to the now-inevitable impacts of climate change. The lack of political science expertise and research represents an obstacle for adapting to climate change, because adaptation is fundamentally political. Technical advances in adaptations for infrastructure, agriculture, public health, coastal protection, conservation, and other fields all depend on political variables for their implementation and effectiveness. For example, adaptation raises questions about political economy (adaptation costs money), political theory (adaptation involves questions of social justice), comparative politics (some countries more aggressively pursue adaptation), urban politics (some cities more aggressively pursue adaptation), regime type (democracies and authoritarian regimes may differently pursue adaptation), federalism (different levels of government may be involved), and several other fields of study including political conflict, international development, bureaucracy, migration, media, political parties, elections, civil society, and public opinion. I review the field of climate change adaptation and then explore the tremendous contributions that political scientists could make to adaptation research.

By Laura A. Henry and Lisa McIntosh Sundstrom | This article accounts for the gap between Russia’s weak initial implementation of the Kyoto Protocol and its more active engagement in climate policy during the Medvedev presidency. We examine the intersection of climate policy and broader efforts to modernise Russia’s economy, drawing attention to synergies between domestic and international politics. We argue that international factors alone do not explain the change in climate policy as they have remained relatively constant. Instead, greater attention toward climate policy results from efforts to introduce new technologies and increase energy efficiency, spurred by the recent financial crisis and a shift in domestic policy priorities associated with the Medvedev presidency.

By Graeme B. Robertson | Since the end of the Cold War, more and more countries feature political regimes that are neither liberal democracies nor closed authoritarian systems. Most research on these hybrid regimes focuses on how elites manipulate elections to stay in office, but in places as diverse as Bolivia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Serbia, Thailand, Ukraine and Venezuela, protest in the streets has been at least as important as elections in bringing about political change. The Politics of Protest in Hybrid Regimes builds on previously unpublished data and extensive fieldwork in Russia to show how one high-profile hybrid regime manages political competition in the workplace and in the streets. More generally, the book develops a theory of how the nature of organizations in society, state strategies for mobilizing supporters, and elite competition shape political protest in hybrid regimes.