Image credit/license

The Republic of Georgia will hold highly consequential elections on October 26. This is the first parliamentary election conducted under a fully proportional electoral system, the first since Georgia was granted EU candidate status, and the first since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. It also marks twelve years since the governing party, Georgian Dream, first claimed a majority in the parliament. The party has steadily introduced reforms that could bias the election results in its favor. The election outcomes and the extent to which they are contested by opposition supporters will help determine Georgia’s foreign policy, as Georgian Dream attempts to chart a more pro-Russian path without undermining the country’s aspirations for full EU membership.

All of this takes place during a period that the interim report of the OSCE election observation mission describes as “entrenched political polarization.” This memo presents the results of a survey experiment conducted in late August (approximately two months before the election), aimed at understanding polarization in Georgia, Georgians’ attitudes toward election integrity, and the likelihood of post-election protest. The results show that: 1) most Georgians remain largely unpolarized, 2) the degree to which respondents are polarized appears largely uncorrelated with age, gender, education, or economic status, and 3) there are clear signs that supporters of Georgian Dream are more polarized than supporters of the opposition. This pattern is likely to lead to a self-perpetuating cycle of polarization and election malfeasance. Policymakers may wish to seek ways to interrupt this cycle, where opportunities for institutional reforms arise from potential cooperation between the Georgian government and the EU and United States.

Polarization and Democratic Backsliding

Concerns about polarization have been echoed by other observers. The 2024 Nations in Transit report on Georgia, produced by Freedom House, opens by stating that “Political polarization and party-led radicalization continued to shape Georgian politics.” Additionally, a delegation from the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe noted that “polarization of the political landscape has reached unprecedented levels” in Georgia ahead of the election.

Scholars have regularly highlighted polarization as a threat to democracy and democratization and have identified multiple forms that polarization may take. In ideologically polarized societies, factions’ policy positions are clear and situated far apart in the issue space. When societies experience this phenomenon, which may be especially harmful to democracy, members of society’s main groups come to view each other as dangerous—to the in-group, the constitutional order, or both. In particular, deeper polarization may incline citizens to tolerate undemocratic behavior by their leaders, to avoid having the opposing side take control of the government (Svolik 2019, Graham and Svolik 2020, Aarslew 2022, Kingzette et al 2021). This creates incentives for incumbents to take actions that undermine free and fair elections. More recently, drawing largely on the US experience, polarization centered around political leaders has been posited as a possible factor in deepening social polarization.

Survey Results: Political polarization in Georgia

The survey obtained responses from 1,037 Georgians, who were asked a variety of questions to estimate the degree of different types of polarization. To capture left-right ideology, respondents were asked whether the government should take more responsibility for people’s welfare or if individuals should. To measure affective polarization, respondents were asked how warmly they feel toward ordinary supporters of Georgian Dream and the UNM. Lastly, to assess leader affective polarization, respondents were asked to rate the current prime minister (from Georgian Dream) and the current leader of the UNM. For the latter to measures, I subtracted respondent’s evaluation of the UNM from their evaluation of Georgian Dream. Higher scores thus indicate more pro-government polarization, while larger negative scores indicate more pro-opposition polarization.

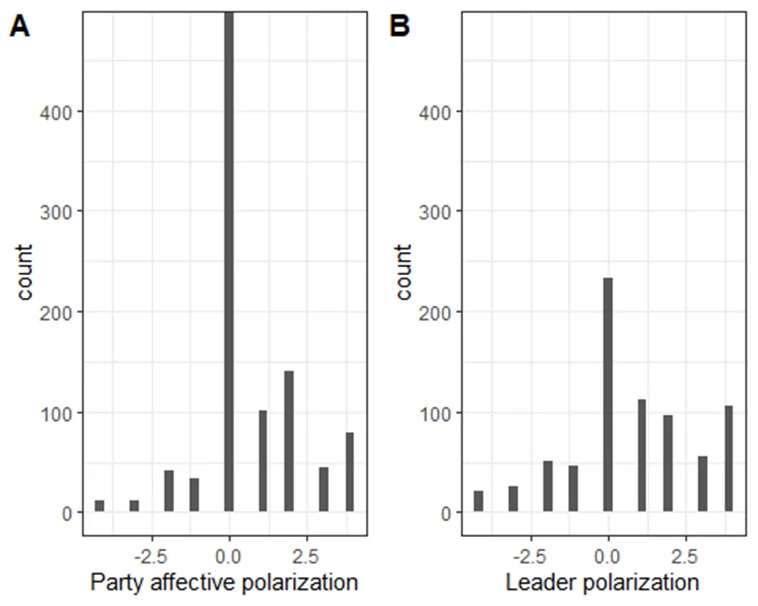

In general, it appears that the modal citizen in the survey is not strongly polarized on any dimension. Figure 1 shows the plurality of respondents rates the parties (Panel A) and their leaders (Panel B) equally, resulting in a score of 0. In both panels, polarization appears to tilt primarily in favor of the ruling party. The minor differences in the two distributions are attributed to the relative lack of name recognition for the UNM leader, Tinatin Bokuchava—approximately 250 respondents had no opinion of her.

Figure 1: Distribution of attitudes toward ordinary supporters (panel A) and leaders (panel B) of UNM and Georgian Dream. Negative numbers indicate greater polarization toward UNM, positive toward Georgian Dream

Figure 1 suggests that Georgian Dream supporters exhibit more polarized attitudes than others and breaking out the results by partisan ID bears this intuition out. The plurality of respondents did not identify with any political party. Out of 1037 respondents, 258 claimed that Georgian Dream was closest to them politically. 150 named an opposition party, while 434 claimed no party.[1] Disaggregating the polarization responses by partisan identification reveals the following patterns.

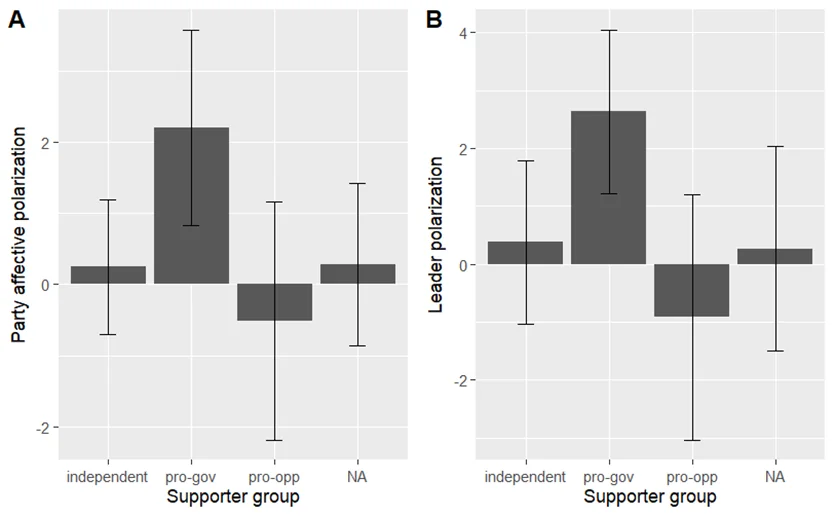

Figure 2 shows the average level of party and leader polarization across four groups: those who identified as supporters of Georgian Dream and the UNM, declared independents, and those who declined to answer. As the figure illustrates, Georgian Dream supporters are far more polarized than other groups; that is, they view their party and leader more positively and the UNM more negatively than do others. This effect is slightly more pronounced for evaluations of the leader compared to the parties.

Figure 2: Distribution of polarized attitudes by supporter group

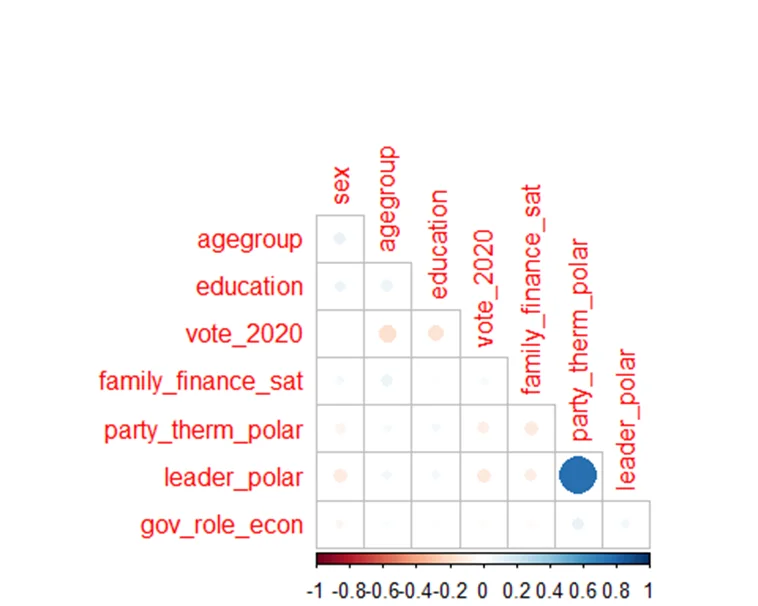

Figure 3: Correlations between demographic factors and polarized attitudes

Demographic factors are only weakly correlated with polarization of any sort. Figure 3 graphically presents the correlations between several demographic variables and three indicators of polarization. The circles in each cell in the figure represent the correlation between two variables; larger circles with darker shading indicate a stronger correlation. As the figure shows, correlations are quite weak across all factors (except, of course, between party-based and leader-based polarization).

Taken together, the survey results suggest that Georgian Dream has been successful in cultivating a positive image for itself and its leadership, while amplifying negative attitudes toward the UNM. Government supporters feel much more positively about their own group, and more negatively about UNM supporters than the reverse. Table 1 reports these averages; the rightmost column shows that government supporters are more than four times as polarized as opposition supporters, by this measure. This reflects, in part, the considerable fragmentation of the opposition (broadly understood). The 150 respondents who claimed to support a party other than Georgian Dream were split across sixteen other parties, including the UNM.

| Supporter group | Avg. approval of GD supporters | Avg. approval of UNM supporters | Difference |

| Independent | 3.00 | 2.72 | 0.28 |

| Pro-gov | 4.28 | 2.09 | 2.19 |

| Pro-opp | 2.55 | 3.07 | -0.51 |

Table 1: Party affective polarization by supporter group

Implications For the Election and Beyond

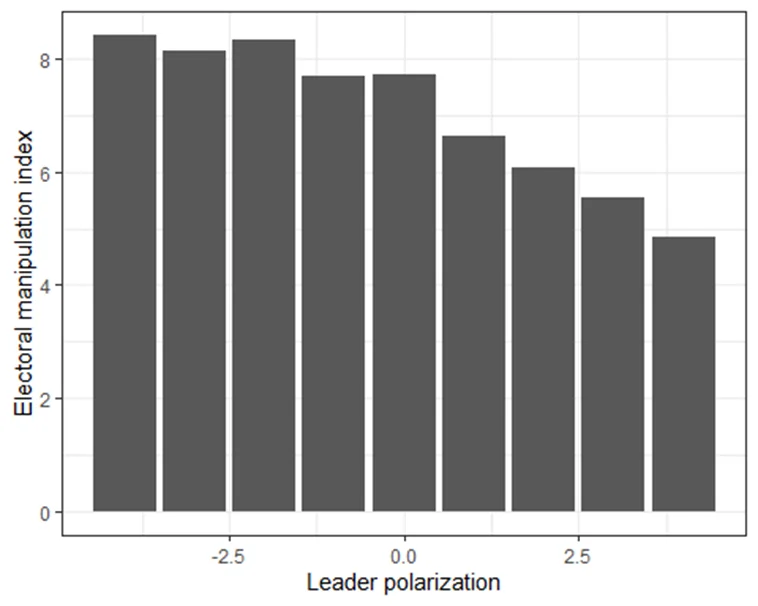

How might these findings influence expectations for the 2024 parliamentary election and the future? First, it is important to note that attitudes toward election integrity are strongly correlated with leader (and party) polarization. In the survey, respondents were asked to evaluate the integrity of Georgian elections on three dimensions: votes being counted fairly, the Central Election Commission behaving fairly, and parties competing fairly for votes. Figure 4 shows the average value for the sum of these three variables across various levels of leader-based polarization. Higher values indicate respondents believe elections are more unfair across these dimensions. As the figure illustrates, those who are more polarized toward the opposition have a very dim view of election integrity in Georgia, an attitude which is shared by the modal respondent with a polarization score of 0. By contrast, the more polarized respondents are toward Georgian Dream, the more confident they are that elections in Georgia are fair.

Figure 4: Leader polarization and subjective belief in election manipulation

To investigate how polarization may influence the election and the post-election period, this survey experiment randomly assigned respondents one of three treatments. In each case, respondents were asked to imagine that Georgian Dream wins a majority in the October election. In the control condition, respondents were told that independent media and analysts considered the election to be free and fair (the ‘clean election’ condition). In a second condition, respondents were informed that independent analysts believed that laws passed by Georgian Dream made it more difficult for the opposition to campaign for votes (the ‘biased laws’ condition). Finally, a third group of respondents were told that independent analysts found evidence of widespread ballot stuffing and falsification (the ‘election fraud’ condition).

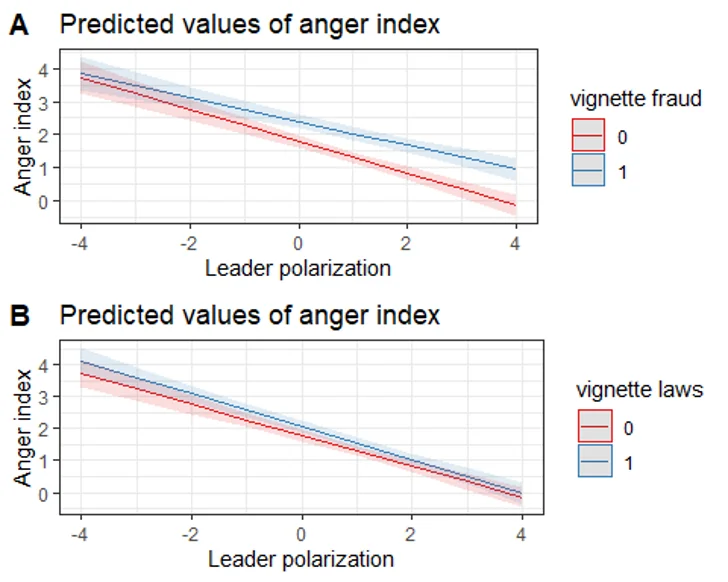

After hearing the vignette, respondents were asked several questions about how they might react to such a scenario. In particular, they were asked to rate their emotional reactions across several emotions (anger, fear, happiness, etc.). Here, I focus on respondents’ anger, as feelings of anger can be strong motivators for engaging in politics generally and protest specifically (Valentino et al 2011, Van Zomeren et al 2012, van Stekelenburg and Klandermans 2013). Statistical analysis indicates that respondents’ degree of polarization influences how they respond to the different treatment conditions, on average. Figure 4 visually presents these results.

Panel A compares respondents in the ‘election fraud’ condition to those in the ‘clean election’ condition; Panel B compares those in the clean condition to those in the ‘biased laws’ condition. The two lines indicate the relationship between leader polarization (on the x-axis) and respondents’ reported anger about the election, for each treatment group. As would be expected, the more polarized respondents are in favor of the UNM, the angrier they are likely to be; they are less likely to be angry about the election when they are polarized in favor of Georgian Dream. However, two additional and important patterns also emerge.

First, outright fraud appears to be a much riskier strategy for the incumbent to pursue than relying on legal forms of manipulation. Panel A in Figure 4 shows that individuals who are not already highly polarized toward the opposition express significantly higher levels of anger in the fraud condition than in the clean election condition. Notably, this is true of the largest swath of respondents—the unpolarized citizens who report no difference in their feelings toward the prime minister and the leader of the UNM. It is also true that respondents who are polarized toward Georgian Dream report much higher levels of anger in the fraud condition than in the scenario where their party won cleanly. One way to put this: a respondent in the fraud condition with a zero-polarization score is about as angry (on average) as a respondent in the clean election condition who is moderately polarized in favor of the opposition—a sizable shift. Employing illegal election fraud, consequently, runs the risk of fracturing the pro-Georgian Dream coalition and increasing the likelihood that unaligned citizens will mobilize with the opposition.

By contrast, Panel B shows there is no such effect for biased laws. Across all levels of polarization, those in the biased laws condition report levels of anger that are no higher than those in the clean condition. This suggests that the marginal risk of employing these tools in the election is quite low. Taken together, these results suggest that—despite efforts to politicize the election administration in recent months—fraud and falsification are likely to be sporadic, with the ruling party relying on its other (legal) advantages to prevail.

Finally, and most importantly, the results suggest there may well be some post-election mobilization by opposition supporters regardless of the integrity of the election. As Figure 4 shows, respondents who are highly polarized toward the opposition report elevated levels of anger when asked to imagine a Georgian Dream victory—whether that victory is clean or manipulated. This is similar in concept, though of course not in the details, to the large protest against certifying the 2020 presidential election in the United States. The US is, of course, a highly polarized country; it is the only country in the comparative study by Reiljan et al (2024) where leader polarization exceeded party polarization, as it does (modestly) in this survey of Georgia.

Figure 5: Effect of fraud and biased laws on respondent anger, by level of polarization

These results highlight ongoing risks to democracy in Georgia should polarization continue to deepen. Beyond the known incentive for more polarized voters to support undemocratic actions by in-group leaders, the pattern observed in Figure 4 makes further legal erosion of election integrity more likely. If incumbents expect their opponents to be equally angry (and prone to collective action) whether they hold a clean or biased election, the electoral benefits of bias may outweigh the risk of protest. In other words, by fostering a tendency for each faction to resist even legitimate electoral victories by the other, polarization deepens the incumbent’s incentives to engage in manipulation.

It is in this context that Georgian Dream has approved measures that 1) make it more difficult to organize sustained protest, and 2) tilt the electoral playing field. In October 2023, parliament approved a law restricting the use of tents and other structures in protest encampments, with violations punishable by up to 15 days in jail. Despite significant protests, the parliament approved a ‘foreign agents’ law in May 2024; the law requires that organizations receiving more than 20% of their income from a ‘foreign power’ register with the Ministry of Justice and provide ongoing financial disclosures. The Venice Commission of the Council of Europe found that the law’s “restrictions to the rights to freedom of expression, freedom of association and privacy are incompatible with” the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Additionally, Georgian Dream has moved to increase political control over the Central Election Commission, placing nominations under the control of the prime minister and requiring approval by a bare majority in parliament (rather than a cooperation-inducing supermajority).

These efforts are likely to continue in a self-perpetuating cycle. As the ruling party entrenches its legal advantages, opposition supporters are likely to become more polarized. As polarization deepens, post-election protest will become more likely regardless of the fairness of elections. This, in turn, will drive further efforts to reduce electoral fairness. Finally, to the extent that Georgian Dream is able to insulate itself from electoral pressures, it may be more successful in pursuing a pro-Russian and Euroskeptic foreign policy, despite the unpopularity of those positions among the public. Policymakers may wish to consider the ways in which international cooperation, such as the EU accession process, can be utilized to interrupt this cycle.

[1] The remaining 104 respondents declined to answer.

Dr. Harvey is an assistant professor at Oklahoma State University. He studies non-democratic politics, with a particular focus on electoral manipulation in authoritarian and hybrid regimes.

Image credit/license