Defying months of unprovoked, brutal, deeply traumatizing Russian military invasion, the Ukrainian society has not only mobilized for defense but has struck back with surging support for its popularly elected president and for democratic values and institutions. It has also struck back with overwhelming confidence in military victory, understood as pushing the Russian forces out of all or most of the currently occupied territories, as well as with readiness to fight over a long haul. Moreover, this rallying for democracy combined with resilience hardened by war losses is precisely at the heart of Ukrainians’ resolve to win, overriding social divides, fear of privation, and Russian media influence.

We draw these conclusions from a statistical analysis of a new panel survey of Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences Institute of Sociology (UNASIS), with funding from the Program on New Approaches to Research on Security in Eurasia (PONARS Eurasia) and fieldwork carried out by the reputable independent Ukrainian polling agency Rating Group. The survey included interviews this July with 475 respondents from among 1,800 people UNASIS polled in November 2021. This pool of repeat respondents turned out to be broadly representative of the population in territories now under Ukraine’s government control, based on key traits such as age, gender, language use, and region. Understandably, due to intense warfighting and Russian occupation, the 2022 survey included very few respondents currently residing in the Donetsk, Luhansk, and Kherson regions (oblasts) and respondents who fled the country.

Horrors of War

The surveys document the devastating impact of Russia’s massive onslaught on the lives of ordinary Ukrainians.

- Close to 70 percent of respondents in July 2022 reported at least one form of war loss—losing homes or businesses, having to flee, getting wounded, or having friends or family killed, wounded, go missing, or displaced. This is a more than threefold increase on November 2021 among the same individuals. At that time, the reported losses resulted from the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine over the Donbas region that had been ongoing since 2014.

- The number of respondents who reported having family members fighting in the war or directly assisting fighters jumped from 5 to 33 percent, and nearly 84 percent said they personally knew at least one person at the front.

- The analysis of respondents’ location at survey time in 2021 and 2022 shows that 18.5 percent had moved to a different region within Ukraine. Our data does not capture the mass exodus of refugees going to neighboring countries in the first weeks of the war and the mass return home after Ukraine’s forces pushed the Russian army out of the northern parts of northeastern Ukraine. But it does capture the movement of people from the east to the center and from west to east, the latter possibly related to assisting the war effort as well as to providing humanitarian assistance or helping with cleanup and rebuilding in the liberated areas.

- The share of respondents—the same people in 2021 and 2022—reporting recurrent tension or anxiety rose from 26.5 to 43 percent; nervousness when being alone from 10 to 33.5 percent; and war-related nightmares from 4 to 34 percent. Forty-four percent of respondents in 2022 expressed fear of state collapse, and 45 percent—fear of going hungry, an increase from 24 and 34.5 percent, respectively, in 2021.

Democratic Fightback

Facing death, destruction, dislocation, trauma, and uncertainty daily on a mass scale, Ukrainians rallied for democracy. One of the authors’ relatives in Kyiv explained with passion: “Look whom we fight. The monster tyranny. Of course, we mobilize for freedom.” This is not just an individual opinion but a prevalent public mood.

- The number of respondents telling us that democracy is very important to them and that it is the best form of government increased by wide margins. And Ukrainians expressed their support for democracy with greater clarity, as evidenced by significant reductions in hard-to-say or doesn’t-matter responses (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Importance of Democracy

- Ukrainians also rallied for their institutions—and not just for the armed forces as would be natural at wartime in any society. We record a sea change among Ukrainians with surging levels of trust in institutions such as the media, the parliament (Rada), and the police (see Figure 2), entities clearly not held in high public esteem before Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Figure 2. Public Trust in Ukraine’s Institutions

- This surge in trust is also part of the mounting sense that Ukraine rightfully belongs to the core alliance of democracies: support for joining the European Union rose among the 475 repeat respondents from 53 percent in December 2021 to about 84 percent in July 2022. Similarly, support for joining NATO rose from 48 to 70 percent. Notably, we observe a stronger level of support in Ukraine since the full-scale war broke out for joining an international organization prioritizing shared political and social norms and relying strongly on “soft power” than for a primarily military alliance, which happens to be the only entity that wields military capabilities superior to Russia’s.

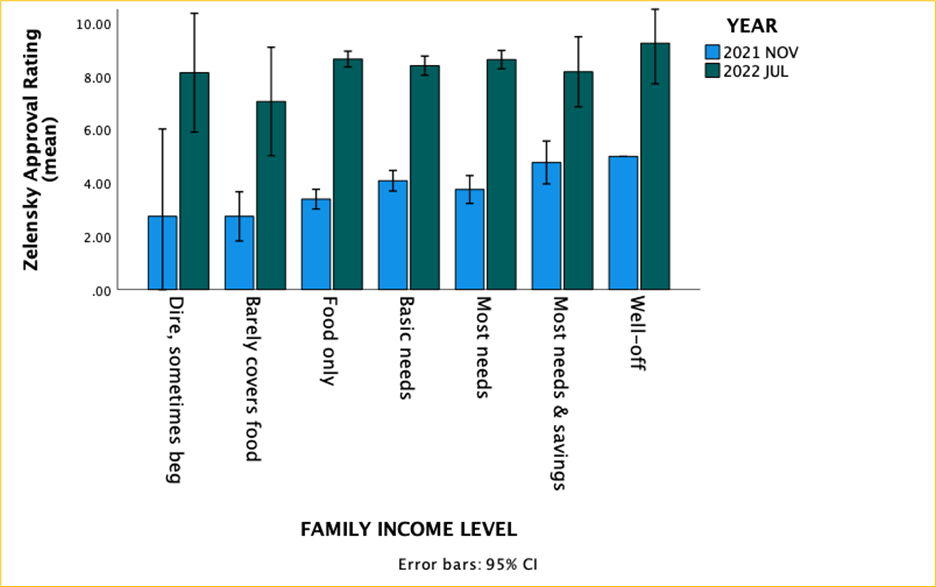

- These trends are intrinsically related to the massive surge of approval for President Volodymyr Zelensky. His arrival in office in 2019 with 73 percent of the vote marked Ukraine’s fifth peaceful transfer of chief executive authority through elections internationally certified as competitive and fundamentally free. (Political scientists view one such transfer as a hallmark of a successful democratic transition). He also became the first Ukrainian president who came to office by carrying all provinces of Ukraine except one, effectively erasing the three-decades-long east-west political split. And Zelensky’s response to President Joe Biden’s offer to flee to safety in February 2022 (“I don’t need a ride, I need ammunition”) amounted to an affirmation of his commitment to the nation and the right to govern on behalf of its people.

- Mistrust of the president, typical of Ukraine’s midterm trends, gave way to trust. The same respondents who, in December 2021, on average, rated Zelensky’s job performance as 3.8 (poor) on a 1-to-10 scale now rated him at 8.9, with 50 percent rating him at 10 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Zelensky’s Performance

The democratic rally cut across the region, age, language, income, education, media sources, and perceived causes of the 2014 Donbas war. Moreover, key groups that were significantly less likely to support democratic values and institutions and Zelensky before Russia’s full-scale invasion now supported them at about the same rate as others. Concerning democracy importance, those were respondents who said they got most news from the Russian media and those who believed local separatists were Ukraine’s principal enemy in the 2014 Donbas war. Concerning trust in the media and parliament (Rada), those were respondents in lower income and education brackets and residents of Western Ukraine. Concerning Zelensky’s approval, those were respondents who lived in the south and the west, respondents with lower incomes, and respondents over 55 years old.

It was also Ukrainians with lower income and education levels and middle-aged respondents, as well as respondents speaking mostly Russian at home and residents of Ukraine’s south and east who used to express significantly lower support than others for NATO and EU membership in 2021 but now expressed it about as strongly as others. Figure 4 illustrates these patterns.

Figure 4. Democratic Rallying Transcends Social Divides

Unity In Freedom

The July 2022 survey showed how this convergence of democracy and leadership has been part and parcel of the growing sense of shared national belonging. When asked how they first and foremost identified themselves, 82 percent said “as citizens of Ukraine” (as opposed to residents of their village, town, city, region, or of the former Soviet Union)—an increase from 63 percent in November 2021 among the same people. And based on UNASIS data going back to 2000, this sense is unlikely to dissipate easily. Regardless of Ukraine’s trials and tribulations, it persisted upward after similar (and smaller) increases in 2004 and 2013-2014, despite temporary dips (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Self-Identification

For Liberty, Through Death, We Stand

Despite facing an enemy that has occupied 20 percent of Ukraine’s territory and that presses on with its manyfold advantages in military capabilities, population, GDP, and natural resources, about 80 percent of respondents in our July 2022 survey reported being fully confident and another 18 percent mostly confident in Ukraine’s victory. The latter is widely understood as pushing Russian forces out of all or most of the currently occupied territories. Survey data show this faith is intrinsically linked to the tidal wave of rallying for democracy in defiance of Russia’s massive invasion. Our statistical analysis controlling for multiple indicators finds that:

- Ukrainians’ confidence in victory transcends distinctions by age, gender, language, income and education levels, region of residence, stress (anxiety), and expectations of the war duration. Notably, based on our July 2022 poll, most Ukrainians are ready for a long war, with 40 percent expecting it to last from six to twelve months and another 23 percent—for more than a year.

- Complete faith in victory is more likely not only among respondents highly approving of Zelensky’s performance and fully trusting the army but also among those fully supporting Ukraine’s EU membership and considering democracy to be very important to them personally. Only two factors undermined this faith: getting most of one’s news from Russia and anticipation of severe privation, particularly going hungry. However, while statistically significant, these impacts are substantively small and mostly translate into a larger number of respondents who say they believe in victory mostly rather than fully (as opposed to losing faith in victory). For example, about 90 percent of respondents said most of their news comes from Russia and still believes in Ukraine’s war victory (with two-thirds of those saying they believe in it fully).

- Our findings point to the “iron triangle” of resolve formed through persistent and mutually reinforcing democracy support, trust in the army, and desire to join the Euro-Atlantic community. The heat map (see Table 1) shows these indicators have also remained strongly interrelated from 2021 and 2022, forming core aspirations of the Ukrainian people. And Table 1 also indicates that Zelensky’s popularity surged in 2022 as it came to be strongly linked with all these aspirations, something that was not the case in 2021.

- Experience with adversity matters, too. A lot of it has to do with Ukraine living through a Russia-induced war over Donbas since 2014 that claimed over 14,000 lives by early 2022. Respondents who reported war loss in 2022 had a stronger belief in victory, all else being equal. And that is interesting because those same respondents were no more or less likely to trust the army, approve of Zelensky’s performance, or want Ukraine to join the EU (see Table 1). However, they have retained their support for joining NATO and now feel that democracy is important to them (something the same respondents didn’t feel as much in 2021). Given how war shocks clarify priorities, they are likely telling us what most Ukrainians want above all at the end of the day: military power enough to push Russia out and thus safeguard their freedom.

Table 1. Associations Among Significant Drivers of Ukrainian Confidence in Victory

Implications for U.S. Policy and International Security

Ukrainians’ democratic resilience is strong and deep. Our surveys indicate that Ukrainians’ faith in victory is not related to how they view the effectiveness of international military, economic, diplomatic, and humanitarian assistance. They understand it is their country and nation to defend, and nobody will do their job for them. At the same time, we clearly see how acutely Ukrainians feel the need to enhance their military capabilities and how strongly they associate them with a chance to build a peaceful democratic future and join the core Western alliances.

In fact, 74 percent of respondents in July 2022 indicated they wanted to see more military assistance and 50 percent more economic assistance from other countries to prevail in the war against Russia. With that, our findings clearly indicate that the United States and other international military aid will not only help Ukraine defend its territory and save lives but will also sustain Ukraine’s democratic aspirations. The best support for democracy in Ukraine is military assistance of the kind that would help Kyiv, in the nearest possible term, achieve the same kind of successes in the south and east of Ukraine as it achieved in the north earlier this year.

Successfully supporting Ukrainians will send big messages globally. Most importantly, it will show that the United States and its allies genuinely stand for democratic nations’ sovereignty, deflating what one might call the Kuwait syndrome argument (i.e., that Washington would only help nations against external aggression when its energy security is threatened). This is important not only on moral and reputational grounds. It would directly bear on the future strategic calculus of any expansionist autocrat contemplating the use of military force, the most notable issue being Taiwan. Also, supporting Ukraine’s democracy in defiance of Russia will boost the power of expectations for the better among democracy supporters worldwide facing overwhelming odds. And that would inspire them to counter grim global trends of the past decade toward authoritarianism and erosion of democratic institutions—trends that threaten the proliferation of autocracies and the return to the dark ways of the past in world politics.

Mikhail Alexseev is Professor of Political Science at San Diego State University.

Serhii Dembitskyi is Senior Research Fellow in the Institute of Sociology at the National Academy of Sciecnes of Ukraine.