When designing an opinion survey on immigration attitudes in Russia that a reputable Levada Analytical Center carried out in 2005, I included a measure of extreme xenophobia used in Eurobarometer surveys. In a Russia-wide multistage random sample, 680 respondents were asked if they agreed or disagreed with the statement: “All migrants—legal and illegal–-and their children should be deported to where they came from.” Close to 43 percent of them agreed—more than double the EU average at the time. In the summer of 2013, another reputable polling agency, ROMIR, asked the same question to 1,000 similarly sampled respondents across Russia. About 47 percent of them again agreed.[1]

This memo offers a preliminary systematic investigation of this persistence of extreme xenophobia in Russia in the last decade through the prism of individual-level perceptions. The 2013 ROMIR survey—resulting from the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) project on “New Russian Nationalism” in which this author participates[2]—asked many of the same questions that were asked in the 2005 Levada survey covering significant hypothetical correlates of anti-migrant hostility in mainstream political and social research. The emphasis was on group threat (security and economic competition), intergroup bias, social contact, and the immigration security dilemma. First, I examined if and how public views on these issues changed from 2005 to 2013.[3] Second, I ran statistical tests on how these views were related to support for wholesale deportation of migrants in 2005 and in 2013. The resulting analysis offers insights on how to think about continuity and change in xenophobic attitudes in Russia and elsewhere. In particular, persistent social isolation of migrants and uncertainty about state strength are likely to sustain xenophobia even as economic circumstances improve and intergroup bias weakens.

Group Threat: “Essentialization” of Security

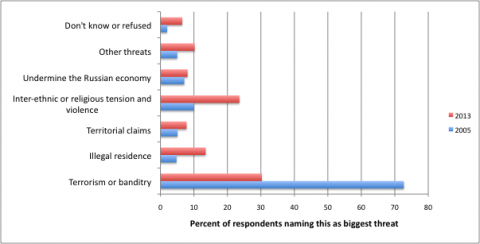

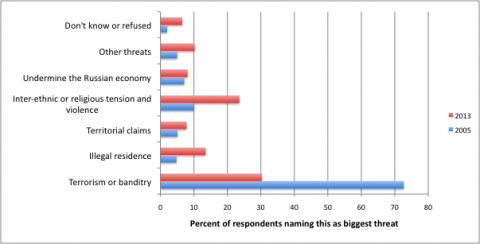

The number of respondents who saw migration as a threat to Russia’s security was about the same in 2005 and 2013–most likely 85 percent based on indirect survey measures.[4] However, opinions on the nature of the threat changed significantly. While fear that migration may give rise to terrorism plummeted, fear that migration may give rise to illegal settlement and ethnic and religious conflicts spiked (Figure 1) .[5] This probably reflects the changes in Russia’s social and political context over the last decade or so. On the one hand, as the separatist wars in Chechnya drifted into the past and as the casualty count in the ongoing anti-government insurgency in the North Caucasus subsided after 2011, terrorism and banditry became less plausible threats. On the other hand, violent conflicts pitting native Slavs against ethnically non-Slavic migrants persisted and some erupted in mass horrific events, such as Kondopoga in 2006 and the Manezh Square riots in late 2011. The pogroms in Moscow’s suburb of Biryulyevo in the fall of 2013 suggest that the social tensions underlying the earlier instances of mass violence remained substantial at the time of the ROMIR survey. In this environment, threats to stability and security are easily viewed as threats associated with essential group identities, such as ethnicity and religion.

Group Threat: Weaker Grounds for Economic Competition

Respondents’ household incomes significantly improved and unemployment declined from 2005 to 2013, thus weakening the staple correlates of economic threat. The median incomes reported per household member increased from 3,000 rubles in the 2005 Levada survey to about 12,500 Rubles in the 2013 ROMIR survey. Moreover, in 2005 respondents were also asked how much money per household member it would take for them to live comfortably (“have a normal life”). For the Russian Federation, the median was 8,000 Rubles. This suggests that by 2013 most respondents achieved household income levels they desired in 2005—with a substantial cushion for inflation. The number of respondents saying they were unemployed due to lack of work—making them likely to blame their job loss on migrants—declined from 5.4 to 2.3 percent. While within the combined sampling error in absolute percentage-point terms, this decline is more than twofold in relative terms and is consistent with the general economic improvement.[6] The number of respondents who picked “undermining Russia’s economy” as the greatest threat associated with migration remained low—with 7 percent in 2005 and 8 percent in 2013. Perceived vulnerability to job competition with migrants slightly declined, although not enough to exceed the combined sample error. About 72 percent of respondents in 2005 and 68 percent in 2013 still supported restrictions on hiring migrants.

Intergroup Bias: Softer on Ethnicity, Harder on Religion

One of the most striking changes from 2005 to 2013 was the rise in number of respondents who said ethnicity does not matter when it comes to marriage—from about 13 to 23.5 percent. In 2013 respondents showed less opposition to their family members marrying migrants who are Chechens, Armenians, Azerbaijanis, and Kazakhs. [7] At least as pronounced was the increase in number of respondents who agreed fully or in part that Islam is a threat to Russian culture and stability—from 43 percent in 2005 to 62 percent in 2013.[8] Self-identification as a Russian Orthodox believer also increased significantly—from 65 percent in 2005 to 78 percent in 2013. Accounting for most of this increase was the drop in number of respondents who said they did not consider themselves religious believers—from 26.5 percent in 2005 to 17 percent in 2013.[9] This means a significant hardening of Russia’s traditional religious in-group identity. These trends pull in different directions—the first one would reduce xenophobia, the second would enhance it.

Social Contact: Russia No “Melting Pot”

The most significant change (from 4 percent in 2005 to 16 percent in 2013) was the rise in number of respondents who said they had business contacts with migrants (other than shopping) during which they got acquainted. However, the number of respondents saying they had migrants as friends, acquaintances, or coworkers declined from 47 percent in 2005 to 36 percent in 2013. Despite receiving millions of migrants since 1991, the number of Russians who reported having migrants as neighbors stayed the same from 2005 to 2013 (about 13 percent of respondents in both surveys). This means the prospect for diminishing anti-migrant hostility through habit and interpersonal contact have remained limited in Russia over the last decade.

The Security Dilemma: State Less Weak, But Not Stronger

Only 15 percent of respondents in 2005 and 13 percent in 2013 agreed that ethnic diversity—which increases most rapidly as a result of migration—makes Russia a stronger state. Notably, the number of respondents who believed ethnic diversity weakened Russia declined from 42 to 25 percent. However, the difference translated only into more respondents saying diversity both strengthens and weakens Russia—i.e., it raised ambivalence about migration impacts. One implication of this reluctance to see ethnic diversity as a source of state strength was evident in the unchanged level of public support for giving preference to ethnic Russians when filling top government posts. About 77 percent of respondents in both 2005 and 2013 surveys agreed with that idea—a form of blatant ethnic job discrimination that Russia’s constitution prohibits.

Media Use

Despite the difference in question wording, one observes a major shift from television to the Internet as a news source among Russians. In 2005, nearly 87 percent of respondents said they got most of their news about migration or migrants from Russia’s top three and Kremlin-controlled television networks (ORT, RTR, and NTV). Only 0.5 percent said they got that kind of news from the Internet (including the web, e-mail, and chat rooms). In 2013, however, 21 percent of respondents said they got most information about current affairs from the Internet. Television remained the biggest news source, but its share dropped to 68 percent. While the 2013 question concerned all news, it is most likely that this shift also affected how most Russians got their news about migration. The effects of this change remain uncertain. Most academic studies have focused on the Internet as a medium for ethnic and religious hate, while some have found that Internet use may promote tolerance.

Statistical Tests: Continuity vs. Change

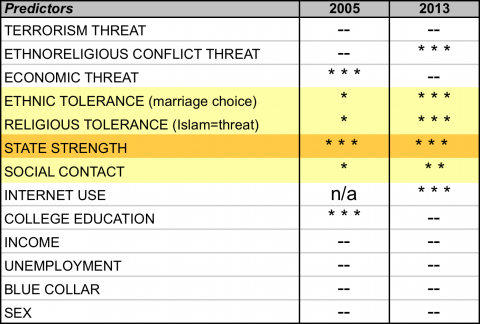

To estimate how each of these views and various factors (income, education, occupation, and gender of respondents) related to anti-migrant hostility in 2005 vs. 2013 while all other views were held constant, I ran a hierarchical ordinary least-squares regression with the survey data. The dependent variable (outcome) was support for wholesale deportation of migrants and their children. The findings are summarized in simplified form in Table 1, based on their degree of statistical significance (i.e., the probability that factors are related to support for deportation by something other than chance).

Uncertainty about the strength of government authority (i.e., fear of anarchy)—a fundamental and unique premise of the immigration security dilemma theory—was the most significant and consistent predictor of extreme anti-migrant hostility. Specifically, fear that ethnic diversity—as a direct and visible outcome of migration—weakens Russia was related more significantly than any other view to support for wholesale deportation of migrants both in 2005 and 2013. In 2005, 44.5 percent of those who believed ethnic diversity weakened Russia supported deportation, whereas only 28.4 percent of those who believed ethnic diversity strengthened Russia supported deportation. In 2013, 50.3 percent of those who believed ethnic diversity weakened Russia supported deportation, whereas only 34.3 percent of those who believed ethnic diversity strengthened Russia supported deportation. Given the large sample size, these differences are highly significant statistically (less than 0.1 percent probability that they occurred by chance alone in both surveys). No other relationship was significant at this level. The significance of group identification—ethnic and religious—is conceptually related to the same concern about anarchy, as is the perceived threat of ethnic or religious conflicts. Their significance, however, fluctuated over time and increased from 2005 to 2013. At the same time, concerns about economic competition declined and were no longer a significant predictor of anti-migrant hostility in the 2013 survey.

Having friends among migrants was also significant in both surveys—and it was unrelated to perceived effects of ethnic diversity on state strength. Contact in general, however, was not a significant correlate of support for deportation. Respondents who said they used the Internet (37 percent of the 2013 sample) were significantly less likely to agree with deporting all migrants from Russia. Out of 692 respondents who answered the question on deportation, only 39.5 percent of the Internet users supported deportation, whereas 54.4 percent of the non-users supported deportation. This suggests that the pool of those who are influenced by hate messages online was marginal in the sample. Rather, the finding may imply that more educated respondents—who are more likely to use the Internet—were less hostile to migrants.

Conclusion: Strength in Kindness

At first glance, the principal findings are counterintuitive. After all, since 2005 the Russian government substantially increased spending on the military, the police, emergency relief, and other security-related agencies (collectively known as siloviki). Top government appointments and allocation of state resources have also favored siloviki. Massive military and police deployments in the North Caucasus have constrained radical Islamist insurgents. The number of terrorist attacks and fighting casualties declined. A small, fast, and victorious war against Georgia in 2008 strengthened Russia’s military presence in the Caucasus and improved Moscow’s control over its once restive Southern borders. Large-scale energy and infrastructure projects reasserted the Kremlin’s authority in East Siberia and the Russian Far East, with the 2012 APEC Summit in Vladivostok marking Russia’s new rise in Asia. Salaries continued to be paid, individual incomes rose, and unemployment fell. Government economic policy minimized the impacts on Russia of the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. The Russian government also showed strength by cracking down on illegal migration. The Federal Migration Service was put under the control of the MVD (police) and fines for employing undocumented migrants were raised significantly. Patrols and sweeps have been carried out with increasing numbers of siloviki forces and resulted in a growing number of arrests, detentions, and deportations of migrants.

Given these developments, one would expect uncertainty about state strength and its impact on xenophobia to decline. Yet, this has not happened. The survey data suggests why this may be the case. The Russian state has gotten stronger, but not kinder. It has failed to integrate migrants into Russia’s society. Fewer respondents in 2013 reported having migrants as friends or acquaintances compared to 2005. Significantly, more respondents now fear ethnic clashes—a large number of which result from failure to integrate migrants and from massive security sweeps of markets and hostels. The policies undertaken to make Russians more secure have probably made them less secure. Migrants are expected to adapt or assimilate into Russian society, whereas society is not expected to become more inclusive or diverse. Russians who believe ethnic diversity would make their country stronger remain a marginal minority.

This implies that to be perceived as strong, a state needs not only to provide guns and butter in abundance, but also to become more relaxed and accepting of the increasing ethnic and religious diversity that ultimately results from the liberalization of global market forces. This means that anti-migrant exclusionism is a dangerous policy for Russia. It is tempting to score quick and easy political points by playing up to widespread xenophobic views. A wiser strategy for the state would be to adapt to the market forces. Fighting them, as the surveys tell us, will erode Russia’s domestic security and stability.

Figure 1. Greatest threats associated with migration, 2005 and 2013.

Table 1. Regression of support for deportation of all migrants and their children from Russia on select predictors.

Note: Asterisks mark level of statistical significance: *** means less than 0.1% probability that the relationship occurred by chance alone; ** — no more than 1% probability of chance; and * — no more than 5% probability of chance. The more asterisks, the more plausible a relationship. Based on N=680 (2005 Levada survey) and N=1,000 (2013 ROMIR survey).

[View PDF]

[1] To make the comparison over time substantively meaningful these numbers throughout the memo exclude the missing data (respondents who refused to answer or said “don’t know”—about 8 percent in 2005 and 9 percent in 2013 on this particular question). In both years, about half of those who agreed said they agreed fully with the statement on deportation.

[3] Significant means the difference in response frequencies to a question in the 2005 and 2013 surveys must exceed the combined random sampling error of the two surveys, approximately 7 percent.

[4] Counting “don’t knows” in both surveys, those who identified “damage to nature” as the primary threat in 2013 and the average of the number of respondents in 2005 who said Armenians, Chechens, Azeris, and the Chinese migrants posed no threat to Russia’s security.

[5] The excluded missing data was about 2 percent of the sample in 2005 and 6.5 percent in 2013.

[6] At the very least, this shows that economic improvements did not result in increased unemployment which could have offset gains in median individual income levels.

[7] The only exception was acceptance of Chinese migrants as marriage partners, which remained at the same level. In both surveys, about 90 percent of respondents were ethnic Russians.

[8] The excluded missing data was 19.2 percent in 2005 and 8.6 percent in 2013. This difference means that respondents who held back their views in 2005 were more likely to consider Islam a threat and more willing to express these opinions in 2013. However, this explains only about half of the increase of the hostile perception of Islam.

[9] The excluded missing data was 2.7 percent in 2005 and 6.1 percent in 2013. For 2013, the number of non-believers includes those who said they were not believers (14.2 percent) and atheists (2.8 percent).