(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) One of the catchphrases employed by U.S. and Russian officials during negotiations, “strategic stability,” is presented by them as a key shared objective that could form the basis for a constructive dialogue between the two adversaries. A clear-cut and globally attractive concept at the end of the Cold War, strategic stability has been marred and heavily depleted of meaning by conflicting interpretations over the three subsequent decades. Most recently, the failure of Moscow and Washington to renew commitment to a consensual understanding of strategic stability was caused by their concerns with the stability and behavior of domestic political regimes—their own and those of potential nuclear proliferator states. While the contradictions surrounding strategic stability as a subject of U.S.-Russian negotiations remain virtually intractable, the commitment of the sides to continuing such negotiations may indicate the lack of immediate plans for brinkmanship in their mutual relations.

Stability as Security

The idea of strategic stability emerged in the 1980s as the international community came to realize that a nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union would not just be impossible to win but would also put the survival of the whole of humankind in jeopardy. As the Cold War was coming to an end, the two nuclear superpowers were looking for ways to provide mutual reassurance and prove to other countries that they did not need to worry anymore about being held hostage to an outbreak of hostilities between Washington and Moscow. A key part of that effort was declaring the commitment of both sides to what they called “strategic stability.”

The initial purpose of the concept was to provide an authoritative description of the conditions under which the threat of a major globally destructive conflict between the two nuclear superpowers would be reduced. In their June 1990 Joint Statement on Future Negotiations on Nuclear and Space Arms and Further Enhancing Strategic Stability, the sides defined strategic stability essentially as the lack of incentives to conduct a nuclear strike. They promised to seek agreements that would “improve survivability, remove incentives for a nuclear first strike and implement an appropriate relationship between strategic offenses and defenses.”

While at the time there existed several alternative concepts of strategic stability, the one that Moscow and Washington put forward as they were gearing up for START I and II negotiations met the basic criteria of clarity and rigor. Such definition did not commit the sides to avoid all conflict under any circumstances. It did, however, imply that in peacetime, the sides will do what it takes to reduce the risk of nuclear weapons being used in a conflict between them, thus making the world much more secure. The absence of incentives for a first nuclear strike was a particularly useful definition of the desired state of relations between Russia and the United States because it provided very clear guidance for arms control. Having thus committed to arms control in good faith, the sides had the moral right to ask that “other States should also make their contribution toward the attainment of [strategic stability], in particular in the field of nonproliferation of nuclear weapons.”

Evolution of the Term

Unfortunately, the simple, brilliant definition of strategic stability soon fell out of grace. As a consequence, arms control negotiations based on the rationale of reducing incentives to conduct a first strike collapsed. Signed in January 1993, the START II treaty, which would have banned multiple warheads on ballistic missiles, thereby reducing the likelihood of a surprise nuclear strike, never came into force.

Over the subsequent three decades, three groups of arguments against the sustainability of the classic definition of strategic stability were put forward by one or both main stakeholders:

- The emergence of advanced non-nuclear weapon systems and means of statecraft (high-precision conventional and space weapons, information warfare, assisted regime change, etc.) could help attain the strategic goal of defeating and subjugating the enemy on par with nuclear weapons. Admittedly, this requires including those systems and methods under the rubric of strategic stability.

- New geopolitical contradictions among major nuclear-armed states supposedly put those who subscribe to the classic definition of strategic stability at a disadvantage (that is, to refrain from nuclear brinkmanship).

- The emergence and self-assertion of new nuclear-armed powers make a bilateral U.S.-Russian definition of strategic stability outdated and useless.

Those arguments were used to justify the dumping of the original consensual, clear-cut, and politically effective definition of strategic stability. Three decades after it was adopted, the two nuclear superpowers only proved capable of agreeing, at their June 2021 summit, on a declaration to the effect that a nuclear war “must not be fought.” Such a declaration differed from the seminal 1990 view of strategic stability in that the signatories of the former refused to rule out the possibility of one or both of them being “left with no other choice under the circumstances” but to employ nuclear weapons. The declaration stopped short not only of asserting the no first use (NFU) principle (to which the United States reportedly came close in the early years of the first Obama administration) but also of any concrete action, apart from continued negotiations, that the sides promise to undertake in order to reduce the likelihood of a nuclear war.

It is also important to keep in mind that while arms control is an effort contributing to strategic stability—including by helping to avoid arms races, a form of instability—the simple 1990 definition of strategic stability did not pre-determine any arms control policies or agreements. It only required that the relevant parties commit to measures—technical and political—that would reduce the incentive to use nuclear weapons first. It means that the classic notion of strategic stability—and the corresponding political commitment to observing it—can hardly be refuted on the grounds of the evolution of technology and the ensuing challenges for arms control. Neither is parity in any type of armaments between the United States and Russia a sine qua non for strategic stability: promising not to engage in nuclear brinkmanship is a noble goal from all perspectives, so preserving the balance of power is a lame excuse for allowing any stakeholders to compromise such a goal.

The justifications for refuting the classic definition of strategic stability and removing it from the basis of arms control negotiations are disingenuous—at least from the perspective of non-nuclear armed states and the global community which has been interested in minimizing the risks of purposeful nuclear detonations. For example, why not keep aiming to reduce the risk of the first use of nuclear weapons, even if nuclear-armed states (aside from China and India) are unwilling formally to commit to NFU? If states cannot rule out the possibility of going to war with another state, why not promise that they will do their best to only use conventional weapons—in line with the classic concept of strategic stability? What is new about the current geopolitical differences and those that existed when the classic definition of strategic stability was in vogue? Finally, what is the problem with extrapolating the bilateral concept of strategic stability to a multilateral setting in which nothing prevents as many nuclear-weapon states as possible from nuclear brinkmanship as the utmost threat to the survival of humankind?

Ever since the sides began to question the original concept of strategic stability, a paradox became evident. While continuing to declare commitment to strategic stability, the sides eagerly engaged in what would be considered destabilizing activities under almost any definition of strategic stability. Such activities included developing new weapons, exploring and testing new conflict domains, or ruthlessly competing for allies. In so doing, the sides kept demanding that the concept of strategic stability be revised to accommodate the purportedly new realities. Such desired revision would commonly imply broadening the scope of strategic stability by factoring in new weapons (that have just been intentionally developed and deployed), strategies, tactics, and even geopolitical balances of power. Eventually, that rendered the originally neat concept of strategic stability barely meaningful and resulted in its dilution beyond credibility for almost any audience, including the two nuclear superpowers themselves.

Tinkering with the classic understanding of strategic stability has not helped to assuage the fears of those actors that feel hostage to nuclear standoffs among major powers. The evolution of the concept kicked nuclear arms control negotiations off course and undermined faith among benign international actors in the commitment of nuclear superpowers to the global survival of humankind—the core inspirational slogan of the late 1980s. Strategic stability may have turned into a figure of speech at best and a smokescreen at worst, designed to embellish the actual approach of the two nuclear superpowers to the possibility of resorting to nuclear weapons in a conflict.

Regime Concerns as Drivers of Change

Is there a way to summarize the cause of the most recent trend towards the unfortunate dilution of the concept of strategic stability—an originally powerful and reassuring imperative? In the 1990s, the U.S.-Russian consensus around strategic stability began to erode because of diverging perspectives on the role of missile defenses. Eventually, Washington refuted Moscow’s concerns with the negative impact of strategic missile defense on strategic stability. Those concerns did not look disingenuous given the explicit requirement for an “appropriate relationship between strategic offenses and defenses” stipulated in the 1990 Statement. The difference in perspectives on missile defense was a negotiable issue had the sides agreed to look for a solution in good faith.

However, the next two decades—and especially the 2010s—saw a swift and definitive departure by Russia and the United States from the original concept of strategic stability understood as avoidance of nuclear saber-rattling. Such a trend was caused by fears related to the workings of domestic political regimes.

Russian policymakers thought that adhering to the original definition of strategic stability would deny Russia a powerful equalizer in relations with the West. Focusing strategic stability only on refraining from nuclear strikes was thought of as an attempt to “declaw the Russian bear.” The Kremlin was concerned with the stability of Russia’s political institutions and regime in general, which was believed to be under assault in multiple domains, including direct attempts at regime change orchestrated by the United States and some of its allies. Not unreasonably, nuclear weapons and brinkmanship were considered to be an important deterrent against destabilizing the political regime. Raising the issue of external guarantees of domestic regime security as an indispensable aspect of strategic stability was a major step on the way towards hollowing out the concept.

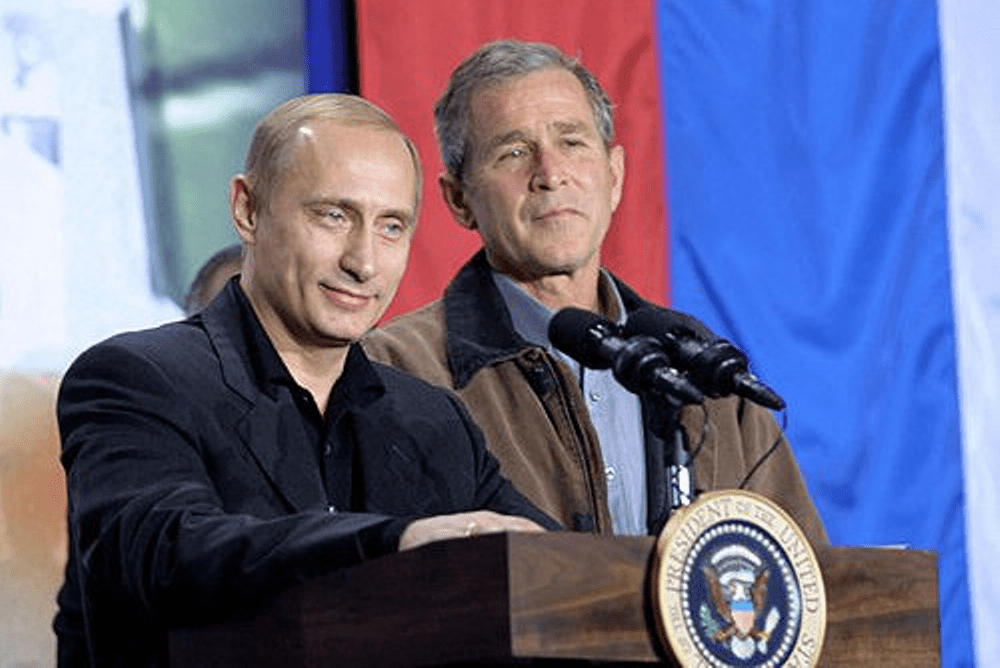

Before too long, the United States also began having second thoughts about the imperative to elevate the threshold for using nuclear weapons. The main reason for their divergence from the classic understanding of strategic stability was concern with the irrationality of authoritarian or theocratic regimes in possession of or in the quest for weapons of mass destruction. In the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR)—the first such document being published in its entirety—Washington reserved the right to use nuclear weapons against such regimes that did not comply with the letter of the Nonproliferation Treaty. The underlying rationale apparently was that if anything could deter those states and regimes from using or threatening the use of nuclear weapons, it would be the likelihood of themselves coming under a nuclear attack—in pre-emption or retaliation. Everything short of such scenarios was not enough to stop them from resorting to doomsday weapons when push came to shove, according to the thinking of at least two recent U.S. (Republican) administrations—the ones of George W. Bush and Donald Trump.

The 2018 NPR also issued a thinly veiled warning to Russia that was thought by American nuclear strategists to be lowering the nuclear threshold and harboring plans for a limited nuclear strike as part of a “escalate to de-escalate” tactic. Under the Trump administration, the United States deployed a low-yield warhead on submarine-based ballistic missiles. This measure was blasted by influential arms control experts as conducive to further lowering the nuclear threshold and being in direct opposition to the seminal 1990 meaning of strategic stability.

Conclusion

If there is a silver lining to this story of the rise and fall of strategic stability, it would be that the concept continues to serve as a litmus test for great power intentions with dangerous global implications. While the sides are no longer committed to pursuing strategic stability, defined as the lack of incentive to conduct the first nuclear strike, they at the very least continue to express interest in discussing strategic stability—whatever its new meaning may be. So long as the sides continue to call for such a discussion, even in the absence of hope for hammering out a new consensual definition, they still signal their basic trust in the lack of mutual plans for a surprise destructive attack. While the end-of-Cold-War imperative of strategic stability has been significantly downgraded in search for a new security equation involving the United States and Russia, the term as such remains relevant and is waiting for a new generation of visionaries to fill it with new credible substance.

Mikhail Troitskiy is Associate Professor and Dean of the School of Government and International Affairs at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO) and IMARES Program Professor at the European University at St. Petersburg. This policy memo is adopted from the author’s article, “What strategic stability? How to fix the concept for US-Russia relations,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, October 21, 2021. The views presented are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of any organization.

PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 723