Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, observers of Russian politics have anticipated a tipping point in Russian mass political behavior. To maintain its military campaign, the Russian regime demands large-scale mass compliance with policies related to the “special military operation.” A prevailing question is: How long will Russian citizens tolerate the human costs of the war and the level of political repression required to sustain the Kremlin’s version of events? After two years, a tipping point away from support for the regime or its policy in Ukraine has not arrived.

Indicators of public opinion, tracked regularly over the past two years, show that perspectives about the war are stable and a majority of the population consistently accepts the Kremlin’s justification for it. Insights from the scholarship of opinion formation in authoritarian regimes, combined with reliable indicators about Russian mass behavior, can help explain this stability. Critics of the regime remain a visible and vocal minority in the population. Those who display public support are a combination of genuine supporters and skeptics.

The two groups are distinguished by their trust in pro-regime media: whereas genuine supporters generally trust these media, the smaller group of skeptics are more inclined to question these pro-regime sources. While repression has limited some private skeptics from becoming public critics, elite-enabling participatory channels that limit public and private supporters from becoming private skeptics have likely played a significant role in stabilizing the Russian regime.

Contextualizing Public Opinion and Tipping Points in Authoritarian Regimes

Political regimes are often considered to be in a stable equilibrium if the population generally complies voluntarily with the demands placed on it by those in political power. When mass compliance is no longer easily achieved, the regime is destabilized and could be at a tipping point toward a new equilibrium. In the case of contemporary Russia, a tipping point away from the stable equilibrium of the Putin regime because of popular dissatisfaction with the war in Ukraine could result in either a shift in war policy or the public turning away from the regime more broadly. To search for potential tipping points, we need to look more closely at trends in mass attitudes and behaviors.

As I noted in a Russia.Post blog post, scholarly findings on opinion formation in non-democratic contexts can provide valuable insights into Russian mass behavior. Barbara Geddes and John Zaller’s 1989 study of the sources of popular support in authoritarian regimes found that when the government has near control over the flow of political communications, exposure to elite discourse tends to induce mass support for the values embedded in it. As the Levada Center’s Denis Volkov recently commented, for two-thirds of Russians, television remains the primary source of information.Moreover, 51 percent of Russians consider state-owned television channels trustworthy, while 20 percent believe state information agencies are trustworthy. These are the primary conveyers of pro-regime propaganda in general and pro-regime interpretations of the war in particular.

Geddes and Zaller also contend that support for the policies advanced by an authoritarian regime is strongest among people who are both heavily exposed to government-controlled communications and lack a context to help them challenge pro-regime messages. Demonstrating this dynamic at work in Russia, Anton Shirikov finds that Russians supportive of Putin “are highly susceptible to propaganda messages and are put off by critical stories from independent media.”

Timur Kuran’s (1995) concept of preference falsification, or “the act of misrepresenting one’s wants under perceived social pressure,” encourages observers to distinguish between individuals’ publicly expressed preferences and their private preferences, which are always hidden. Balancing the social pressure to outwardly express public opinions that differ from one’s private opinions engages different “political thresholds” where a person is likely to switch from one public preference to another. When political thresholds are crossed by a sizable enough segment of the population to disrupt a regime’s stable equilibrium, the regime could be at a tipping point.

Preference falsification exists in all regime types and the true degree of such falsification is unknown. Consequently, small events can produce meaningful shifts that bring a population closer to or move it further away from a tipping point, as individuals consider whether the costs of expressing their private opinions publicly have changed. Multiple events that have taken place over the past two years could have opened the door for a shift to a tipping point in Russia: mass emigration, the partial mobilization, Prigozhin’s rebellion, Boris Nadezhdin’s anti-war presidential bid, Aleksei Navalny’s death, and the recent presidential election. Yet while each of these events may have fostered some shifts in policy preferences, none created the space for a meaningful political opening.

Preference Falsification and Shifting Political Thresholds

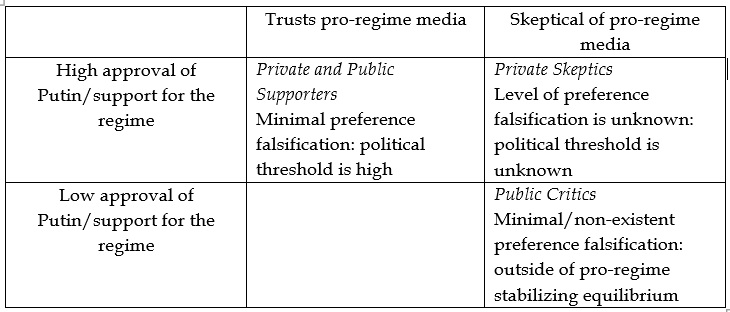

Table 1 outlines a typology of equilibria and political thresholds of support for the Russian regime. The horizontal axis comprises individuals’ level of reliance on pro-regime media. The vertical axis relates to support for the current regime. The cross-section of these two axes produces three distinct categories.

Table 1. Typology of Equilibria and Political Thresholds of Support for Russian Regime

Private and public supporters endorse the Russian regime and generally trust pro-regime media. This category of individuals tends to engage in minimal preference falsification. The political threshold for them to change their public opinion of the regime to disapproval is high. Public critics have low levels of support for the regime and are skeptical of pro-regime media. This group has minimal or non-existent preference falsification. They have come to accept the social, economic, and material sanctions of public criticism.

Private skeptics display a high public opinion of the regime but are skeptical of pro-regime media. They are generally indistinguishable from private and public supporters. Some likely engage in minimal preference falsification and can flow back-and-forth with private and public supporters. For others, the degree of preference falsification may be extensive, to the point that they are approaching the political threshold for becoming public critics. Still others may be continually uncertain as to what their political threshold is. They may be more susceptible to cross over into expressing disapproval of the regime or its policies based on information that comes to them via direct, personal events and private discourse.

Ultimately, a tipping point away from the pro-Putin equilibrium will only be reached when enough individuals cross the political threshold that public critics become a visible plurality of the population. As part of this process, private skeptics must first become a growing segment of the population. Skepticism of elite discourse delivered by pro-regime media must increase and the strength of alternate values must deepen, such that private skeptics ultimately cross the political threshold to become public critics. Since the true size of the category of private skeptics is unknown, at any point in time, public and private supporters and private skeptics could be crossing the political threshold between these two different positions, quietly destabilizing the regime. A closer look at trends in existing public opinion data, together with indicators of mass public behavior, provides a rough estimate of the size and stability of these three groups in contemporary Russia.

Identifying Public Critics, Private Skeptics, and Regime Supporters

Public critics are easily identifiable from a range of indicators and likely comprise about 20-25 percent of the population. As Denis Volkov has suggested, a stable 20 percent of the population is vocally critical of the war and this number has not moved dramatically in recent months. Similar percentages of respondents expressed negative emotions following the death of Aleksei Navalny: 26 percent of respondents to a Levada Center poll reported feeling anger, shock, sadness or bewilderment about it. Responses to Navalny’s death correspond to presidential approval ratings: 53 percent of respondents who disapproved of the president’s performance expressed negative feelings about the death. Levada further reports that those who did not approve of the president were overrepresented among the small percentage of those who approved of Navalny’s actions.

Kremlin propaganda appears to have been effective in limiting Navalny’s impact on shifting the political threshold of private skeptics. Levada Center polling shows that by the middle of 2021, the percentage of the population that claimed to know nothing about Navalny started an upward climb, while the share of those who approved of his work declined substantially. In sum, public critics are a minority, and while their “Noon Against Putin” act of defiance held on the last day of Russia’s presidential election on March 17 was symbolically important, the 96 arrests across 27 cities do not reflect private skeptics crossing the threshold into public criticism.

Differentiating private and public supporters from private skeptics is more challenging, since preference falsification renders these two groups largely indistinguishable on indicators of public opinion. After two years of war, Putin’s approval rating remains high, at 85 percent in April 2024, a figure virtually unmoved since October 2023. Scholars using sophisticated analytical techniques—such as the placebo tests employed by Timothy Frye, Scott Gehlbach, Kyle Marquardt, and Ora John Reuter—point to a general consistency in the trendline of Putin’s approval, including an uptick in Putin’s popularity after the invasion. Drawing on Levada Center monitoring, as of February 2024, among those who rely primarily on television for their information, 82 percent believed the “special military operation” was proceeding successfully, a view shared by 76 percent of those who approve of Putin.

Additionally, if we examine indicators of concern about socio-economic problems (inflation, unemployment, poverty, etc.), the trend line shows that worry over these issues began to decline prior to the February 2022 invasion and has continued apace. These tendencies suggest that private and public supporters comprise a larger segment of the population than private skeptics. Data from both the Russian Election Study and Levada’s March 2024 monitoring, however, suggest that Russians could be wearying of the war, creating space for a rise in private skeptics.

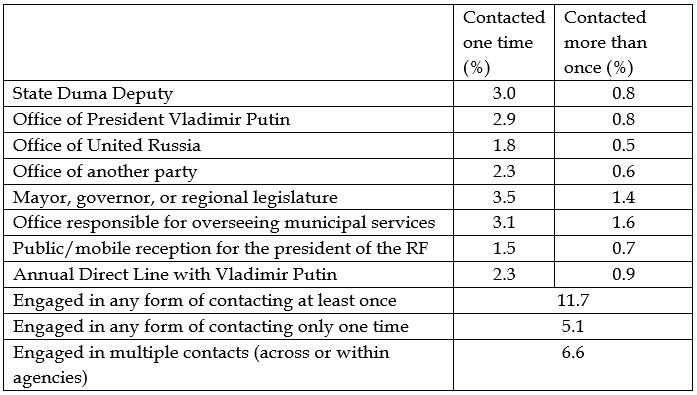

Both private and public supporters and private skeptics have continued to provide feedback about their policy concerns through accepted, conventional participatory channels. Russians’ longstanding preference for expressing their criticisms, requests, and concerns by appealing directly to political elites is a form of elite-enabling political participation that has stabilized the Russian regime by providing governing elites with key feedback to address localized policy concerns and preempt their eruption into the broader political arena. A series of questions I was able to include on the Russian Election Study following the Fall 2021 Duma elections (Table 2) showed that more than 11 percent of Russian citizens have contacted a public official at some point, and more than 6 percent have contacted a public official more than once. As Table 2 reveals, citizens contact a broad range of offices at the local, regional, and national level. For comparison, other questions included in the same survey revealed that only 4.8 percent of respondents had engaged in any campaign-related activities prior to the Duma election. Russians are more likely to appeal to public officials than to use electoral or protest channels to express their concerns.

Table 2. Russian Contacting of Public Officials (2021)

N = 2,953 to 2,959 depending on the question

Source: Compiled by the author on the basis of data from the Russian Election Study.

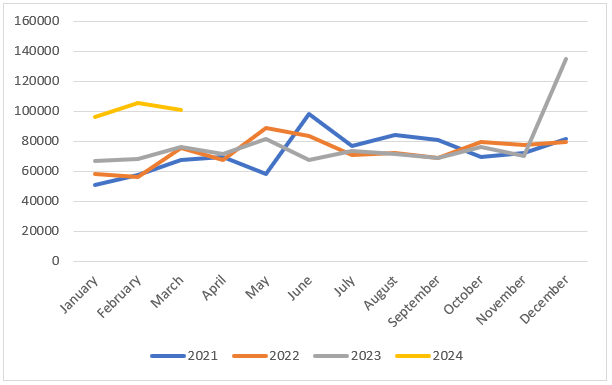

Aggregate data on citizen appeals suggest that Russians are using this mechanism to express concerns about the war. Sasha de Vogel’s analysis of the content of appeals to the Russian Presidential Administration in the year after the full-scale invasion found that by the winter of 2022, almost half of all appeals concerned foreign policy, the military, and Russia’s role in international conflicts. At the conclusion of 2023, the volume of appeals received by the presidential administration had increased substantially over 2022. The Kremlin’s report on appeals attributes the increase to correspondence concerning “defense, security, and legality.” As Figure 1 demonstrates, the number of appeals received by the Presidential Administration jumped considerably in December 2023 and remained high in the first three months of 2024 compared to recent years.

Figure 1. Appeals to the Presidential Administration

Source: Compiled by the author on the basis of data from http://letters.kremlin.ru/digests/.

To the extent that public and private supporters are critical of war-related policy, they are likely expressing these views by contacting public officials, with corresponding policy adjustments being made to keep this group from crossing the political threshold into becoming private skeptics or public critics. Overall, the ranks of the private skeptics have decreased in the past two years due to a combination of successful propaganda, emigration, and responsiveness to citizen feedback.

Conclusion

More than two years after Russia’s full-scale invasion, the Russian regime has remained highly stable by maintaining mass compliance with regime commands. If the regime can ensure that public critics do not become a plurality of the population, a tipping point away from current regime policies is unlikely to be reached. Successful propaganda has maintained a core group of public and private supporters. While repression has limited some private skeptics from becoming public critics, elite-enabling participatory channels that limit public and private supporters from becoming private skeptics have also likely played a significant stabilizing role. The group to which observers must be most attentive are the private skeptics, whose ranks may increase if war-weariness grows.

Danielle N. Lussier is an associate professor of political science at Grinnell College. She is the author of Constraining Elites in Russia and Indonesia: Political Participation and Regime Survival (Cambridge University Press, 2016).