(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) While standard national security interests deal with defending territorial integrity, sovereign authority of government, and economic stability, they can extend beyond this narrow range as leaders choose which issues rise to the level of security threats. Russia’s new National Security Strategy (NSS), published in July 2021, emphasizes the protection of Russian culture, spiritual-moral values, and history as a matter of national interest and security. While the 2015 NSS also included culture, this recent iteration goes further in depicting the extent of threats Russian culture and values face and in recommending the next steps to take. The 2021 NSS groups the United States and its allies together with transnational corporations and terrorists as entities that “actively attack” traditional Russian values. It then proposes a state order on scientific and cultural production designed to preserve Russian values and history with a means of “ensuring quality control.”

This securitization of culture, characterizing it as a national interest under threat from outside forces and internal fifth columns, fits into a broader strategy of nation-building and regime support. By constructing a Russian national identity and narrative that places himself as the nation’s natural champion and protector, President Vladimir Putin hopes to gain legitimacy while shutting out the opposition as enemies of the nation. These dynamics play out in a variety of ways as policies are interpreted and implemented by governmental, semi-governmental, and civil society actors, most recently in contention over theater repertoires. How these interactions unfold and which actors gain control over nation-building messaging impact the usefulness of nation-building as a means of ensuring regime durability.

Nation-Building, Securitizing Culture, and Regime Legitimacy

In autocratic nation-building, regimes aim to construct a version of the nation that maintains the current power structure. This is done through careful selection of symbols and historical narratives that both resonate with enough of the population and can be adopted by those in power. It also requires limiting divergent ideas of what the nation is through the use of administrative resources. In Russia’s case, Putin has engaged in this activity since coming to power, but with increased attention following his return to the presidency in 2012. While his nation-building actions and policies have at times been ambiguous, this flexibility enables the regime to tweak the national narrative and its partnership with different civil society forces as necessitated by the political, economic, and cultural climate of the moment.

Nation-building tactics are varied, but all aim to identify the boundaries of inclusion in the nation, national values and history, and national heroes and enemies. They range from instituting new and manipulating old holidays to deciding which monuments to erect or replace and to exerting control over cultural institutions that can disseminate and reinforce the state-approved national narrative. In these examples, administrative resources include the power to declare or undeclare national holidays, the power to grant or not grant permits for the use of public space in celebrations, ownership of public land and resources for monument construction, and selective application of laws against offending believers to shut down operas.

Once the national boundaries are established, the next stage is securitizing that national culture. Jardar Østbø and Viatcheslav Morozov have each illustrated how the securitization of Russian values and identity has enhanced the Kremlin’s ability to ward off calls for human rights and justify a wide range of foreign and domestic policies as necessary for protecting the nation from Western meddling. When the nation is under threat, support increases for those viewed as doing the protecting and decreases for those painted as enemies. With outsized control over traditional media and participation in nation-building actions over the years, Putin can more easily insert himself as the protector and father of the nation. Having worked to construct a new post- Soviet Russian national identity and then portraying that nation as under threat, Putin and his network of clients can benefit from “rally around the flag” effects even outside periods of active conflict. The rallying effect cannot work, however, without first sewing a flag that is meaningful to a sizeable segment of society and attaching that flag to yourself.

Despite sitting at the top of Russia’s power pyramid, Putin has not been able to dictate what the Russian nation is on his own. Nation-building necessitates involving other actors across state agencies, levels of government, and from civil society. In this competition for power over identity construction and protection, flareups among principles and agents, and among groups with divergent conceptions of Russian identity, are inevitable. The more frequent the misalignment of messages and aims, the less useful nation-building becomes as a legitimacy-building strategy. Once Putin released the new National Security Strategy, those working in the government or in cultural organizations impacted by the contents of the strategy had to determine what the new directives meant for their action.

Theaters, Ministries, and Civil Society

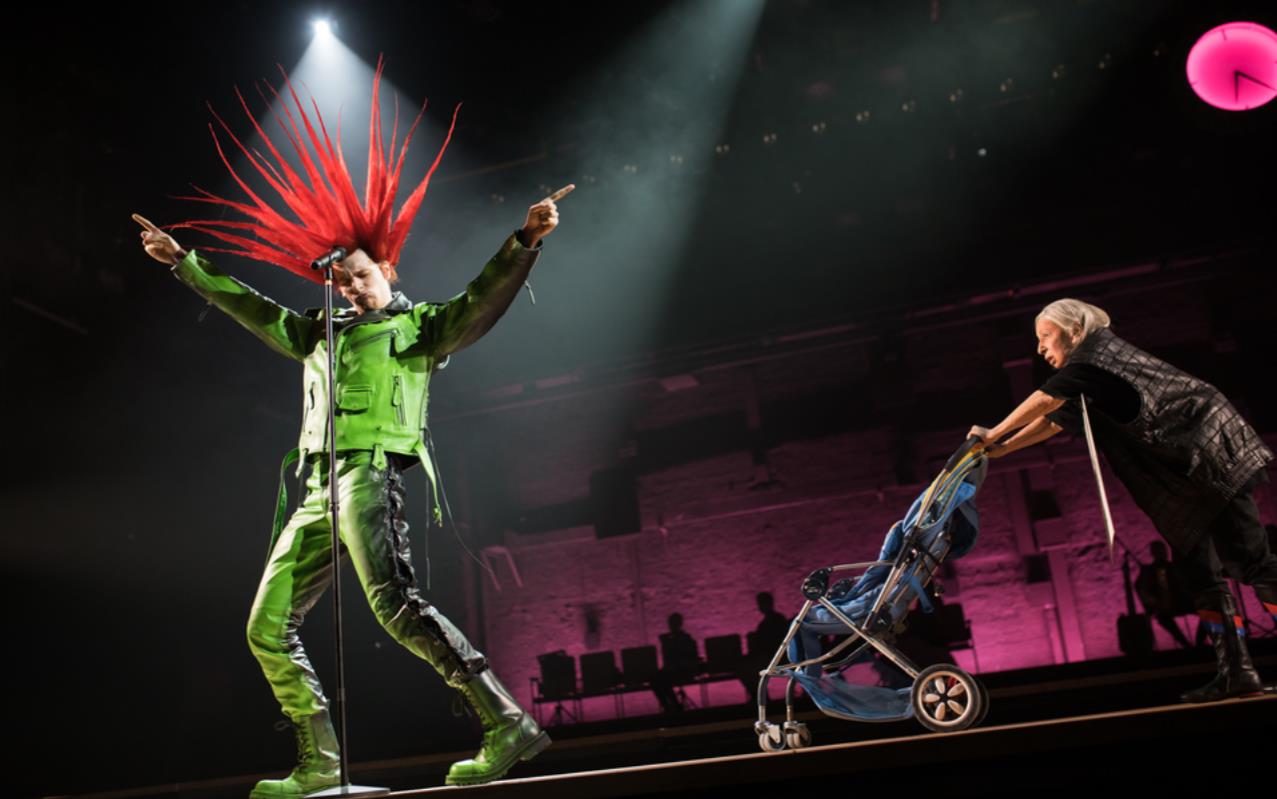

The latest competition for cultural control and understanding of the new National Security Strategy began with controversy involving the play “First Bread” at Moscow’s Sovremennik Theater in July 2021. Actors involved in these negotiations over what cultural productions should be permitted include civil society actors, semi-governmental organizations, and governmental organizations.

Complaints against the play originated from veterans’ organizations, including Officers of Russia and Veterans of Russia, that accused the production of offending veterans, inciting interethnic hatred, and promoting “propaganda of same-sex love,” among other accusations. Because Putin signed a law in April 2021 increasing criminal liability for offending veterans and rehabilitating Nazism, these are serious charges. Opposition to the play also came from SERB, a pro-Kremlin Russian nationalist organization known for disruptive and usually unpunished actions, members of which left funeral wreaths outside of the theater intended to disrupt the performance. These monitors of culture for improper content came from civil society, calling for enforcement of laws pertaining to culture and identity as they see fit.

The civil society boundary blurs in the case of Officers of Russia as some government officials are members of it, and its main activities include “patriotic education and legal education of the population [and] strengthening the rule of law and defense of the country of the peoples of the Russian Federation.” While not officially connected to the government, the organization views its role as supporting government functions. This pressure from below did ultimately have an effect. Russia’s Investigative Committee initiated a probe into the production, and the theater edited the script to remove some of the words seen as offensive.

In the wake of this controversy and with the language of the new National Security Strategy, Mikhail Lermontov, Chairman of the Public Council of Russia’s Ministry of Culture, proposed a new method of keeping theater content in line with official values and culture. He told RIA Novosti that the Public Council will “hold public hearings… on the issue of theater repertoires in terms of compliance with the ‘national security strategy’ recently approved by (Russian President Vladimir) Putin, which has a large section on the preservation of spiritual-moral and patriotic values, all of which is spelled out concretely.”

The Public Council, comprised of 36 figures considered representative of the cultural elites, is designed to link civil society and government. Its tasks include providing expertise to the Ministry of Culture, bringing matters of public interest to the Ministry’s attention, and informing the public of and holding discussions about the Ministry’s actions. In proposing these hearings, the Public Council took it upon itself to start implementing some of the National Security Strategy’s recommendations for protecting national culture and values.

Despite the announcement, Lermontov did not coordinate this plan with the Ministry of Culture to which his Public Council is attached in advance. Olga Lyubimova, the Minister of Culture, commented that the Council did not discuss this proposal with the Ministry and that the Ministry does not have the right to interfere in cultural activities. She stated, “censorship in our country is unacceptable in accordance with the Constitution. At the same time, if in the sphere of culture there are violations of the current legislation, then the competent authorities have the right to give them an appropriate assessment.” In this clarification, Lyubimova distinguished between censorship and legitimate enforcement of laws pertaining to cultural content. She intimates that what Lermontov proposed was censorship while leaving room for the Investigative Committee or the Ministry to undertake similar action if prompted by “violations.”

Actions that appear too close to outright censorship risk disrupting the narrative that threats to the nation are from outside forces rather than from those in power. The Public Council’s proposal of public hearings over theaters’ repertoires challenges the notion that cultural production is only subject to government oversight in limited cases when it violates a law. If the Ministry of Culture were to have firm control over the interpretation and implementation of government policy, the Public Council would serve as more of a one-way channel from the Ministry to the public. This case shows there is some space for independent action and two-way exchanges. Though there are benefits of providing a limited group of cultural elites access to power, such as enhancing the Ministry’s legitimacy and obtaining information on public opinion, it comes with the risk that they will overstep their limits.

In this case, the new NSS and previous laws related to protecting historical memory, veterans, and believers are being interpreted and enforced differently by various actors. It can be useful to the government when some of this enforcement is outsourced to pro-Kremlin civil society organizations. When it is veterans organizations calling for an investigation, accusations of censorship hold less weight. At the same time, there is a danger of overzealous enforcement, such as that proposed by Lermontov and the Public Council, and of oppositional groups using that to challenge the sincerity of the government’s claims of acting in the Russian nation’s interest.

Conclusion

In the past year, the Kremlin has escalated its overt repression to control the opposition. The attempted assassination and imprisonment of Alexei Navalny, increased use of police violence and arrests at protests, and new election laws designed to bar more opposition figures from running indicate that more repressive strategies are coming to the fore at this moment. Some of this overt repression has entered the cultural realm as well, as evidenced by the firing of director Kirill Serebrennikov from the Gogol Center and his conviction on likely trumped-up embezzlement charges. In talking to Meduza, Liya Akhedzhakova, the actress in “First Bread,” whose monologue upset veterans, said, “I don’t know whether [the production] will be back in October or not. I might be sitting in a jail cell then.” The recent examples of investigations, firings, and convictions are making clearer the boundaries of permissible cultural production. Permissible is that which fits in and promotes the official narrative of traditional Russian culture, values, and history. The risk from the Putin regime’s perspective is that the closer the government or pro-Kremlin organizations get to outright censorship and control over culture, the less effective nation-building and securitization of culture are for regime legitimacy.

Katie Stewart is Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations at Knox College.

PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 736

Image credit (Sovremennik)