(PONARS Eurasia Commentary) For over two centuries, experts, politicians, and famous writers such as Nikolai Gogol and Fyodor Dostoevsky have observed the Europe-Russia-China triangle and confronted the infamous Russian policy dilemma: To the East or to the West? Toward Europe or Asia? The predicament endures, but it has sharp new relevance in a new global context due to the economic clout of China. Gone is the perception that Russia is a bridge between East and West. Rather, primarily, it has become a significant commerce and business partner to both. Old and new geopolitical challenges continue to cloud Russian relations with the West, providing strategic opportunities for Moscow to engage more closely with Beijing, even if the Russian nation remains categorically European in its identity.

Nine Key Trends Denoting Rivalry and Friendship

A number of long-term tendencies frame the global context for Moscow.

The First trend is the unprecedented strengthening of China in modern history and its rapidly growing and clearly articulated ambitions for leadership in Asia, the Pacific, and the global economic and geopolitical hierarchy.

Second, it is precisely with the strengthening of China that the refocusing of the global strategy of the West, primarily the United States, is connected—across President Barack Obama’s “Pivot to East Asia, ” President Donald Trump’s “decoupling,” and President Joe Biden’s ”deliberative” approach. In fact, the “Chinese factor” underlies and increasingly determines a significant part of the trade, economic, institutional, legal, and technological initiatives and actions by the United States and the West in all regions of the world, from the Arctic to southern Africa. Equally, the non-participation of China with its huge military potential in arms control treaties was the reason/pretext for the dismantling of most of the basic treaties in this area on the initiative of the United States.

Third is a consolidation of the West, a strengthening of transatlantic ties, and a rapprochement between the EU and the United States on forming a common strategy toward China. This is primarily due to the emphasis of the new Biden administration on strengthening relations with European allies.

Fourth, the COVID-19 pandemic played a significant role in Europe’s reassessment of relations with Beijing, highlighting a whole chain of vulnerabilities in the socio-economic and political structure and in the foreign and economic policy of the West. The danger of over-dependence on the import of critical products in the health sector has clearly manifested itself. Mask and vaccine diplomacy exacerbated distrust.

Fifth, already in 2020, China’s trade, economic and political relations with Western partners began to show trends generated or accelerated by the global epidemiological shock. The pandemic turned a remote or semi-remote type of social and business interactions into normative ones. And, accordingly, it placed the widest range of production of products and services in new places in the scale of national and global development priorities, generating new needs and standards. The localization and renationalization of production chains that began earlier have an additional motivation related to ensuring security.

Sixth, to the greatest extent, securitization has affected the high-tech sector. No matter how long the pandemic lasts, fierce competition in this area will become a stable factor and a key indicator of the global economy and trade.

Seventh, equally, the pandemic will only spur the topic of climate and ecology that has come to the fore. Despite the statements made by the United States, the EU, and China about their intentions to cooperate on the environment, progress may be slow. The best motivator is the restrictions imposed by the EU, which plans for an accelerated transition to a green economy in Europe. The introduction of a carbon tax makes it doubtful that the EU will omit serious contradictions with China on these matters.

The Eighth long-term trend is the ideological themes of democracy and human rights. Suffice it to say, it was rather traumatic for the West in 2020 when authoritarian China fought the pandemic with better results.

Finally, ninth, the most recent, important factor in Western-Chinese relations is Afghanistan. After the withdrawal of U.S. and Western forces, China’s role in the region is significantly increasing, especially in view of, firstly, the uncertainty of development in Afghanistan itself, and secondly, the complexity of problems and contradictions between the countries in the region (namely Pakistan, India, and Iran). China seeks to be more involved in the economic sphere as well as security. Some experts have been suggesting that China is seeking to take control of the extraction of the country’s rare metals and resources, many of which, for example, are critically important for the production of microchips. Countering this idea is that China already has a large share of rare earth elements within its borders.

Russia will have to navigate the multi-faceted rivalry—geographic, economic, political, and ideological—between the West and China for the foreseeable future, not to mention its own frictions with the West. At the same time, the EU is of special importance for Moscow due to at least several principal circumstances.

Moscow noted how the Trump administration demonstrated how Washington could easily neglect the interests of its closest allies. The current deep political split in the United States allows for the possibility of a Republican victory in the next presidential election, and therefore, a potential revision of U.S. policy toward the EU. The China factor keeps the continent highly relevant for Washington. Nevertheless, serious problems in the U.S.-EU relationship may arise in connection with differences in the climate and environmental agenda, the implementation of which will be hindered by the American oil lobby (and probably more so if the Republican party makes gains). In any case, despite the tightening of the EU’s position toward China and its rapprochement with the United States, it is focused on its member states with their own, more narrow, trade, economic, and political interests.

Another circumstance is that both the trade and economic agenda and the security agenda of Russia and Europe in relations with China have more points of contact and common concerns than the Russian and U.S. positions. Moreover, the global context has changed, but not the geography: Greater Europe and Greater Eurasia remain relevant geo-economic and geopolitical concepts. Also, Russia, with all of its known deviations from the classical democratic models of development, sees itself a part of the Judeo-Christian world in civilizational and historical terms—a European country with established centuries-old cultural ties and traditions to European identity.

Numbers, Interdependent Trade, Viewpoints

In the new, emerging global context, perhaps data can help answer the classic Russian “East or West” question. Although China occupies first place in Russian foreign trade in goods by a large margin in the country-by-country rating, the EU, as a whole, is Russia’s largest trade partner. Even in the 2020 pandemic year, the EU accounted for 36 percent of Russia’s foreign trade and China for 18 percent. However, over 2010-2020, Russia’s trade with the EU declined, while its trade with China grew dynamically.

The specific weights of the EU and China in Russia’s foreign trade turnover are rapidly converging, especially in imports. Thus, the EU share in Russian exports of goods decreased by 1.3 times to 40 percent, and imports by 1.2 times to 36 percent. On the contrary, China’s shares increased by 2.9 times to 15 percent and 1.4 times to 24 percent. Moreover, in trade with the EU, Russia has a significant positive balance, but with China, as a rule, a negative one.

The commodity structure of trade is also converging and not in favor of Russia. Both in the EU and now in China, it exports mainly goods of a low degree of processing and added value and imports high-margin technological products that form the potential for economic growth. Russian exports to the EU are dominated by fuels and mining products (about 70 percent), agriculture and raw materials (about 5 percent), chemicals (more than 4 percent), and exports to China, respectively, more than 60 percent, about 8 percent, and 3 percent. Russian imports from the EU are headed by machinery and transport equipment (about 50 percent), chemicals (more than 21 percent), and agriculture and raw materials (about 9 percent), as well as from China (50 percent, 11 percent, and about 4 percent, respectively).

Russian-Chinese trade interdependence is increasing in areas that do not meet the requirements of sustainable, innovative growth for the Russian economy. This trend may become almost irreversible in the mid-term if Russia does not radically improve political and economic relations with the EU, especially in the innovation and technological sphere. Nonetheless, the EU is the largest investor in Russia. In 2019, the volume of EU foreign direct investment (FDI) in Russia amounted to $349 billion. The volume of Russian FDI into the EU is about $152 billion, while into China, it is only about $ 13 billion. China’s interest here is clearly less than the EU and, unlike trade, is not growing. The fact that Russia is the fifth largest trade partner for the EU, representing almost 5 percent of the EU’s total trade in goods with the world in 2020, also speaks for itself. Russia is in 11th place in China’s foreign trade, and the EU is second after the ASEAN countries, but ahead of the United States.

According to experts, Russia’s dependence on machinery and technological equipment imports from China and the EU is high and will increase. The fierce competition between the West and China, especially, for example, in connection with the upcoming 5G technologies, lets Russia develop a strategy that allows for preserving sovereignty as well as freedom of choice (of equipment). Excessive technological dependence on China is assessed by Russian experts as a negative scenario, even while Russia’s national strategy for technological development has not yet been sufficiently developed. For Russia, the importance of developing trade and economic relations with both Europe (EU) and Asia (China) is enormous, although not equal.

What do contemporary Russian society and elites think about the East-West orientation? According to polls conducted by the Levada Center in 2019-2021, Russians have a positive attitude toward the EU, though it is gradually decreasing. In January 2021, 45 percent of Russian respondents had a positive attitude toward the EU, and 37 percent a negative one. Young Russians aged 18-24 years had the best attitudes toward the EU (62 percent positive), while negative respondents were in the 55 year-old-and-older bracket (36 percent positive, 43 percent negative). The attitude of Russians toward China in January 2021 was 75 percent positive and only 10 percent negative (the indicators are approximately the same for all age groups). Russians’ attitudes toward China improved dramatically in 2014 against the background of the conflict between Russia and the West over Ukraine, from 55 percent to 77 percent positive.

At the same time, the polls note a change in Russians’ views, self–perception, and self-identification over the past 11 years. During this time, Russians have been “moving away” from Europe. If in 2008, 52 percent of respondents considered Russia a “European country,” in 2019, only 37 percent did. Further, the share of those who consider Russia a “non-European” country also increased to 55 percent from 36 percent. Levada Center experts noted last year that citizens became less concerned with Western sanctions and the isolation of Russia. They continue to see Russia as a country with a “special path,” although for young people, Europe is an important reference point for opportunities and well-being. For the business and political elite of the country, it may be enough to say that Russia’s upper-middle and wealthy classes keep their savings and invest in Europe.

Conclusion: Competition and Camaraderie

Instability and threats across the south of Russia—in the Afghanistan region, Transcaucasia, and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)—are likely to increase. In MENA, climate shifts threaten water wars and famine. In most cases, Russia and the EU are in the same boat concerning the threat of terrorist acts, uncontrolled migration, and spread of COVID-19 and its variants. U.S. and NATO limitations in settling crises across this “arc of instability” can strengthen cooperation between Russia and the EU. The EU, particularly the Franco-German tandem, will remain pragmatic cooperation partners for Russia in the foreseeable future. Russia’s relations with the EU are finding a new (low) plateau, as seen by the approval of Nord Stream-2.

On a bilateral basis and within the framework of the SCO, China has long been Russia’s partner in ensuring security in Central Asia and in northeast Asia. However, Moscow is clearly aware that Beijing is guided by its own interests and goals, including geo-economic ones, which do not always coincide with Russian goals, although they rarely conflict with them. Russia’s relations with China are defined as a strategic partnership. The Kremlin, though, is in no hurry to raise it to the level of an alliance. China states that there is no need for an alliance at the official level. Both sides do not want to take on excessive obligations or additional restrictions. A sovereign independent foreign policy remains the cornerstone of the philosophy of both regimes, which draws them together.

Irina Kobrinskaya is Head of the Center for Situation Analysis, and Boris Frumkin is a Leading Research Fellow, at the Primakov National Research Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO) at the Russian Academy of Sciences.

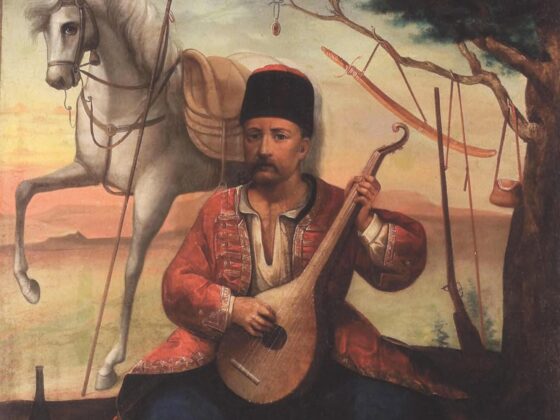

Image credit