Did the full-scale invasion of Ukraine upend protest mobilization in Russia? When and where did Russians take to the streets to express support and opposition to the war? And did protest over issues unrelated to the invasion, such as the economy and the environment, previously on the rise, come to a halt after February 2022? Drawing on protest-event data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) and additional coding, this memo describes Russian protests in the twelve months following the Ukraine invasion.[1] New protest-event data bring greater clarity and evidence to ongoing discussions about the public’s support for the invasion, the consequences of escalating repression, and Russians’ evolving concerns.

As the evidence suggests, anti-war protests were widespread in the hours and days that followed Ukraine’s full-scale invasion. Pro-war protests, orchestrated by the authorities and even systemic opposition parties such as the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, followed the eruption of anti-war demonstrations. The authorities’ response to anti-war protests was more violent than their response to previous waves of protest in Russia’s post-Soviet history. Approximately 9 out of 10 protests organized to express opposition to the war were met with arrests and police brutality. At the same time, other types of protests did not come to a halt after February 2022. Russians continued to take to the streets to advance local, environmental, and other socio-economic demands. The authorities’ more tolerant response to these protests contrasts sharply with their response to anti-war demonstrations.

Pro-War Protests Followed the Eruption of Anti-War Mobilization

The ACLED project represents a valuable source of information about protests in Russia. It provides rich information on individual protest actions and complements projects on the repression of protest and civil society more broadly. To collect information on protests in Russia, ACLED relies on a range of sources, including international and local Russian media, media projects, political parties, and civil society organizations, such as OVD.Info, Activatica, Meduza, and TV Rain. ACLED provides information on the location, size, and type of protests, whether peaceful or violent, and extensive descriptions of each protest action. Drawing on these descriptions, we labeled each protest as expressing political, socio-economic, or other types of grievances. We also coded whether protests taking place across 2022-23 expressed support for or opposition to the invasion and its consequences.

It is important to note that while the dataset includes several “symbolic” protests, such as “silent protests” or acts such as flower-laying ceremonies that resulted in arrests, it does not cover other symbolic acts of resistance, such as painting graffiti or distributing anti-war leaflets. As the costs of protest participation increased in recent months in Russia, street protests gave way to more subtle and symbolic acts of resistance.

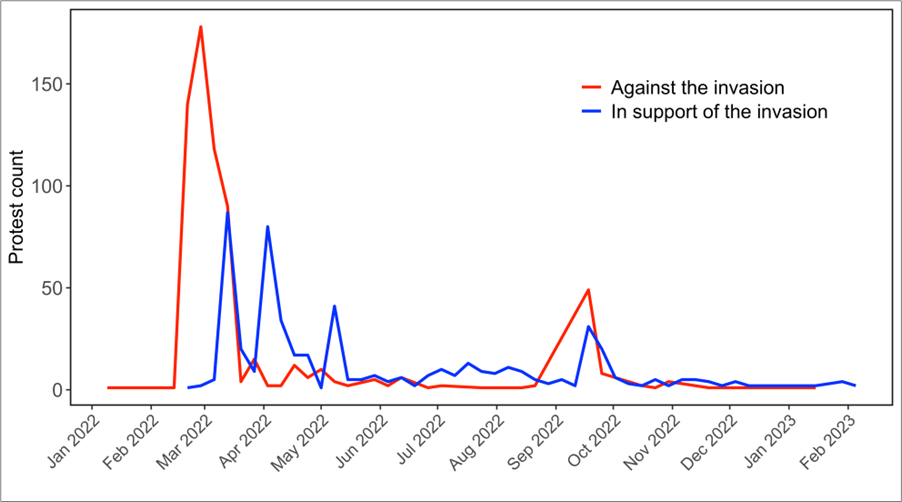

With this caveat in mind, for the period between January 2022 to mid-February 2023, we counted just over 1,200 protest events related to the invasion. These protests correspond to approximately 73 percent of all protests taking place in Russia during this period. Five-hundred-thirty-six protests were organized to express support for the ongoing invasion, and 675 to express opposition. Other protests were linked to the invasion but did not necessarily express support or opposition to the war. Such protests include actions organized by draftees who demonstrated against wage arrears and mothers of soldiers sent to fight in Ukraine who took to the streets to ask for information about their loved ones.

Below, Figure 1 shows the weekly count of protests staged to oppose (red line) and support (blue line) the invasion. Some anti-war protests took place before February 24, with demonstrators opposing the “possible large-scale war with Ukraine.” Anti-war protests spiked dramatically immediately after the military invasion on February 24, 2022, and declined abruptly in mid-March. Legislation that punished individuals for “spreading fake information” about the Russian military and its operations, passed in early March, made it increasingly dangerous to voice opposition. The invasion also accelerated the departure of social movement activists who had the capacity to coordinate large-scale protests, a process already underway since early 2021. Between March and April 2022, the number of anti-war protests declined ten-fold. In July and August, only four protests were organized to express opposition to the war across Russia. In September 2022, the announcement of partial mobilization also coincided with a modest increase in anti-war protest actions.

Pro-war protest, orchestrated by the authorities, civil society groups close to the Kremlin, and Russia’s “loyal” opposition, grew in the spring of 2022, largely as a response to widespread anti-war protests. For example, in February, just a single protest expressed support for the invasion. Contrast this to the 225 protests expressing opposition. Even in March, anti-war protests outnumbered pro-war events at a ratio of approximately 3 to 1. And, as the number of anti-war protests increased in September of 2022, so did the number of pro-war actions. Several of the pro-war protests taking place this time expressed support for the illegal annexation referendums in Russian-occupied Ukraine.

Figure 1: Weekly Count of Protests Against and In Support of the Invasion of Ukraine, January 2022-February 2023

Protest Repression Escalated in the Aftermath of the Invasion

Anti-war protesters taking to the streets during this period faced arrests and police brutality. It is estimated that the police responded with violence, beatings, and arrests to a staggering 92 and 98 percent of anti-war protests taking place in February and March 2022, respectively. In September 2022, arrests were made in 90 percent of anti-war protests. According to data from OVD-Info, around 19,589 individuals were arrested for expressing anti-war positions in the twelve months that followed the invasion of Ukraine. Between February–March 2022 alone, the authorities arrested 15,351 individuals.

Pro-war demonstrators enjoyed the support of the state and of the police. Across all 536 protests organized to express support for the war, just a single demonstrator was arrested. On March 18, 2022, the police in Orenburg arrested a minor who attempted to join a protest in support of the invasion with “Other Russia” stickers on him.

Anti- and Pro-War Protests Took Different Forms Across Russia

Protest actions against and in support of the invasion took different forms. After the violent crackdown on mass demonstrations in the first weeks following the invasion, anti-war demonstrators staged single-person pickets and engaged in other symbolic actions, such as flower-laying ceremonies. For the most part, such acts of defiance remained invisible to national audiences. Yet, as Guzel Yusupova reminds us, even smaller-scale protest and other acts of defiance were meaningful for individuals who engaged in them and for targeted communities.[2]

Anti-war demonstrations were led by citizen groups, particularly women and students, journalists, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning human rights center Memorial, and the opposition party Yabloko. The “Feminist Anti-War Resistance” movement, created in response to the invasion, led several of the protests occurring during this period. Many of these included symbolic actions, such as laying flowers at war monuments. According to commentators, Russian anti-war protests had a “feminine” face due to the increasing numbers of women protestors.

Anti-war protests occurred predominantly in Moscow and St. Petersburg but also in Sverdlovsk, Krasnodar, Novosibirsk, Nizhny Novgorod, and Tatarstan. Approximately 15 percent of all anti-war protests during this period took place in Russia’s ethnic republics. One reason could be that ethnic republics, over-represented in Russian forces fighting in Ukraine, were disproportionately affected by Putin’s partial mobilization. To express their opposition to the draft, women in Dagestan, Grozny, and Makhachkala repeatedly gathered outside military recruitment centers. Other citizens in the North Caucasus decided to express their opposition to the draft by closing down roads. These protests remained uncoordinated and were unable to build momentum. However, anti-war mobilization in the ethnic republics emphasizes the importance of better understanding the origins and consequences of protest mobilization across Russia and the attitudes of people in Russia’s regions most affected by war casualties and the draft.[3]

Pro-war demonstrators, organized by local authorities, war veterans, and other pro-regime civil society organizations, such as the Young Army Cadets National Movement, took the form of larger concerts and demonstrations, motor rallies, and gatherings. Such actions, covered extensively by local and federal media, aimed to portray a country that was rallying around the president and the war. As a recent V-Dem Institute working paper shows, the image of widespread support for the Russian president helps maintain his popularity. Perceptions that support for the invasion is widespread in society could also contribute to Russians’ support of the war.

The Communist Party Was at the Forefront of Pro-War Protests

Following the invasion, public space for political activism shrank. Faced with escalating repression, many activists and social movements with the ability to coordinate protests moved abroad. The Communist Party was one of the few forces that remained in the country with the ability to coordinate nationwide protests. Its stance toward the war was, therefore, critical.

Loyal to its identity as a “systemic” opposition force, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation offered its full support to the invasion of Ukraine and led pro-war protests across the country. According to estimates, Russia’s Communist party staged about a quarter of all pro-war protests occurring during February 2022-2023.

Yet, as the 2022 Russian regional elections neared, the need for the Communists to distinguish themselves from United Russia, Putin’s party of power, grew. Perhaps in an attempt to appear actually to be in opposition, by late spring 2022, the Communists began to stage protests that simultaneously expressed both support for the invasion of Ukraine and criticism of the government’s social and economic policy.

The Invasion Did Not Halt Non-Political Protests

Protests related to the invasion of Ukraine accounted for approximately three-quarters of all demonstrations taking place during January 2022-February 2023. At the same time, according to ACLED, Russians continued to take to the streets to express discontent with local infrastructure or public services such as education and healthcare and poor economic conditions, as well as to advance pro-environmental causes.

Approximately a third of all protests unrelated to the war involved environmental causes, opposition to the construction of buildings in green areas, and dissatisfaction with official decisions to cut down forests or construct landfills near residential areas. Socio-economic protests comprised approximately a quarter of protests not linked to the invasion. These included protest actions against wage arrears, utility cuts, poor working conditions, and events that advocated for increasing student stipends and salaries. Protests against the demolition of historical buildings also continued in the period that followed Ukraine’s invasion.

The authorities’ response to protests not linked to the war was relatively tolerant. Approximately 1 in 5 social, political, environmental, and cultural protests were met with arrests, and only 1 in 10 protests that advanced economic grievances faced repression. The state’s response to these protests contrasts sharply with its response to anti-war protests. Differentiation in the authorities’ violent response to protests echoes evidence from earlier waves of protest. Indeed, several considerations may explain the fact that the authorities are more tolerant of some protests. For example, permitting certain protests could allow the authorities to better identify social grievances and monitor the performance of regional authorities. It may also allow them to signal that as long as Russians shy away from joining anti-war protests, they should be less concerned about repression.

Conclusion

Following the invasion of Ukraine, the Russian authorities moved swiftly to criminalize anti-war protests. “The Russian authorities met early antiwar actions with repressive force and severe legal repercussions for participants,” Sasha de Vogel affirms. The crackdown on civil society meant that mass resistance to the war failed to materialize. Yet, in the context of escalating repressions, activists continued to use adaptive tactics and express opposition to the war. While unsuccessful at shaping Russians’ views of the war, or government policy, women’s anti-war activism and growing mobilization in the ethnic republics could have long-lasting consequences, emboldening demonstrators and targeted communities. The interplay between growing dissent and escalating repression could help shape the future of Russian politics. The need to document and better understand Russian street protests, including symbolic acts of resistance, has never been greater.

[1] ACLED was created at the University of Sussex in 2005 and is currently a non-profit organization based in Wisconsin.

[2] See: Guzel Yusupova, “Silence Matters: Self-Censorship and War in Russia,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 824, January 2023.

[3] See: Kyle L. Marquardt, “Ethnic Variation in Support for Putin and the Invasion of Ukraine,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 823, January 2023.

Katerina Tertytchnaya is Associate Professor of Comparative Politics in the Department of Political Science at University College London. This work draws on the ESRC-funded project Nonviolent Repression in Electoral Autocracies.