(PONARS Policy Memo) Soon after assuming the presidency in 2012, Vladimir Putin launched a series of political and economic reforms intended to strengthen the hand of the central government over Russia’s regions, consolidate presidential executive control over parliament, and restore the state’s solvency. While these various moves earned a great deal of scholarly and journalistic attention, the simultaneous initiative to consolidate society behind a patriotic ideal was less noticed.

In fact, the Kremlin has invested heavily in patriotic education as a unifying idea, beginning with the program “Patriotic Education of the Citizens of the Russian Federation for 2001-2005,” followed by subsequent revisions. These replicate aspects of Soviet-era military patriotism, emphasize service, defense of the motherland, and sacrifice for the state.

When examined from the perspective of ordinary Russian citizens, however, popular understandings of patriotism bear at most a superficial resemblance to state doctrine. Russians understand “being a patriot” in terms of loyalty to the government, but they understand “patriotism” as intensely personal and even opposed to politics. This observation suggests that “preference falsification” (when people misrepresent their privately held views in public settings) is potentially widespread, and that it occurs specifically in the gap between “patriotism” as Russians’ private understanding and “being a patriot” as a socially appropriate and expected expression of loyalty.

The regime’s attempts to cultivate popular legitimacy through patriotic appeals has the potential to exacerbate the gap between public and private, particularly since the Kremlin’s brand of patriotism virtually eliminates ideological space for individualist, pro-regime movements and parties. In the long run, the intensification of patriotic appeals may become a source of friction between regime and citizenry, undercutting the legitimacy of the leadership.

State-Sponsored Patriotism

Starting in the mid-2000s, the state invested in military-patriotic entertainment, particularly film and broadcast media, and sponsored academic conferences on patriotic themes. In primary and secondary education, Soviet history was rehabilitated with particular emphasis on World War II (called the Great Patriotic War in Russia), the modernizing achievements of the Soviet state under Brezhnev, and the USSR’s role and status as a world power. The government also promoted the creation of patriotic organizations at the local and regional levels.

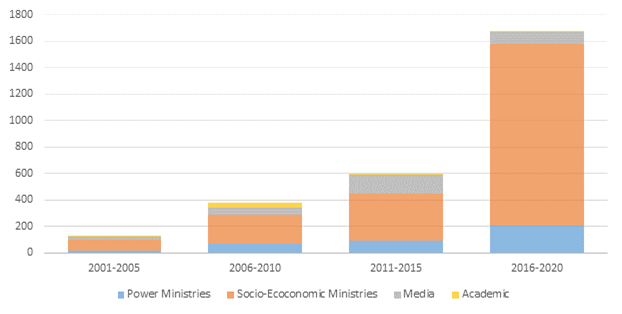

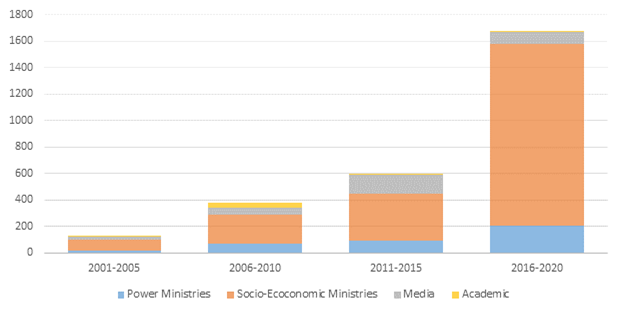

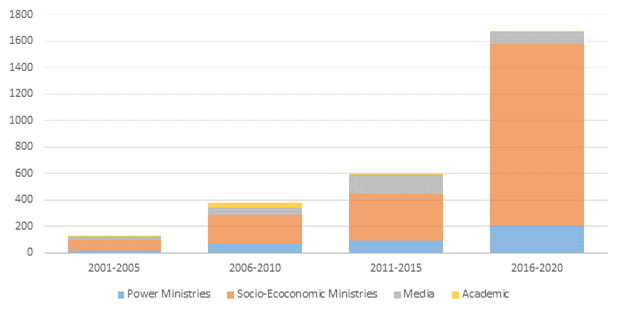

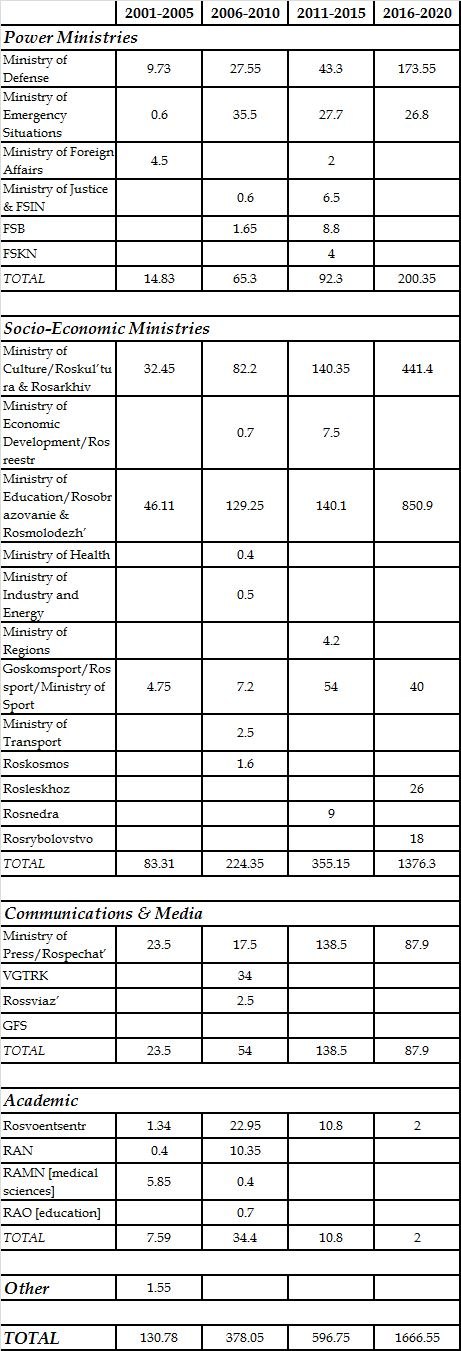

The bulk of funding for the state patriotic programs was allocated for the power ministries in its initial incarnations—particularly for the Justice Ministry for elaborating its legislative strategy—but over time came to focus on the Education and Culture Ministries (see Figure 1). Through its various programs, the patriotic programs attracted various sectors of business and society to participate and become invested in the promotion of patriotism. On the regional level, governors also competed for the center’s resources in promoting their own patriotic events and competitions.

The one-two punch of the Sochi Olympics and the annexation of Crimea in 2014 proved a critical juncture in the development of patriotism as state doctrine. For many Russians, the 1980 Moscow Olympics remain a source of pride, alongside other iconic moments such as Yuri Gagarin’s flight into space. The Sochi Olympics reclaimed that memory, stylistically establishing today’s regime on equal footing with the USSR while making a statement comparable to China’s in the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Russian citizens marveled at the national team’s record-breaking harvest of medals (though this was later brought into question by revelations of a state-sponsored performance-enhancing drug scheme).

The Sochi Olympics were soon overshadowed by Russia’s annexation of Crimea on March 18, 2014. In domestic politics, this achieved record levels of support for the government, disruption of the nationalist opposition, and the chilling of dissent. At the same time, Russia became increasingly isolated in international politics. Russia’s allies failed to support the annexation. The imposition of Western sanctions on Russia’s elite was met by Putin’s “counter-sanctions” in the form of a boycott of European agricultural imports and the official adoption of import substitution.

By 2016, patriotism became the only game in town. As Russia’s economy faltered and relations worsened with the West, the Kremlin doubled down on patriotism as a unifying force that would see it through troubled times. The budget for patriotic programs increased nearly three-fold (see Figure 1 and Table 1). In a widely reported meeting with small business leaders on February 3, 2016, Putin declared:

“We do not and cannot have any other unifying idea but patriotism… [Our national idea] is not ideologized, it is not connected with the activities of any political party or social strata. …we have to talk about it constantly, at all levels.”

Political innovators continue to find new ways to adapt patriotic themes to movements and organizations. In one extreme case, pro-business environmentalists recently called for “ecological patriotism to form the basis for a new national idea” and suggested the Kremlin apply import substitution to groups like the World Wildlife Foundation and Greenpeace.

“Patriotic Education of the Citizens of the Russian Federation” State Programs

Program 2001-2005

Program 2006-2010

Program 2011-2015

http://gospatriotprogramma.ru/the-program-of-the-russian-pvgrf-for-the-years-2011-2015/index.php

Program 2016-2020 (draft)

http://gospatriotprogramma.ru/programma%202016-2020/proekt/proekt.php

Program 2016-2020 (final)

http://government.ru/media/files/8qqYUwwzHUxzVkH1jsKAErrx2dE4q0ws.pdf

According to the 2016-2020 (draft) program, patriotism is defined as:

“The foundational orientation of citizens’ social behavior, expressing a higher purpose in life and individuals’ activities, showing duty and responsibility before society, forming an understanding of the priority of societal interests above individuals, including self-sacrifice, [and] disregarding danger to one’s life and health in the defense of the Fatherland’s interests.”

According to the 2016-2020 (final) program, the essential goals are:

“Creating conditions for raising citizens’ accountability for the fate of the country, raising the level of societal consolidation for resolving tasks related to the provision of national security and stable development of the Russian Federation, strengthening citizens’ sense of co-participation (soprichastnost’) in the great history and culture of Russia, [and] educating citizens who love their motherland and family [and] have an active position in life.”

Patriotism in Citizens’ Daily Lives

Patriotism is now an unavoidable feature of Russian politics, but what does it mean for ordinary citizens in their daily lives? To understand this, I conducted in-depth interviews with 65 respondents in two Russian cities, Perm and Tyumen, in 2014-2015, and commissioned a series of focus groups on the same subject in Perm. If the interviews were useful for investigating the everyday actions and routines (or practices) associated with patriotism, the focus groups illustrated how social dynamics affect the meanings attached to patriotic practices.

In one-on-one interviews, respondents generally expressed an understanding of patriotism that differs significantly from the version advanced by the state. For most Russians, patriotism is intensely personal and idealistic. Among the various meanings and practices associated with patriotism, it most commonly involves a close attachment to the “little motherland” (usually one’s home town or region), raising one’s children properly, doing one’s job, not causing trouble for others, living clean, improving one’s surroundings, consuming Russian products, and choosing not to leave Russia even if one has the means and opportunity.

Two crucial observations emerge from the interviews. First, when patriotism is “authentic,” it is connected with love (for the motherland) or emotion. It is opposed to politics and profit, which concern interest and ambition rather than love and sacrifice. This means that patriotic activities enforced or exploited by politicians and business are perceived as artificial, cynical, and even harmful. The one exception to this is the May 9 celebration of Victory Day, though even here, the holiday’s significance largely stems from familial memories of sacrifice and loss. Otherwise, the activation of patriotism “from above” by the state or media, patriotic performances, or patriotic opposition to political enemies is derisively referred to as “hoorah patriotism.”

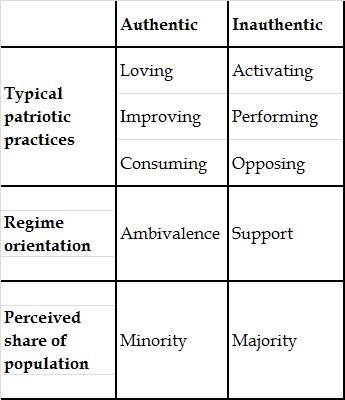

Second, almost all interview respondents assumed their own understanding of patriotism differed from that of their fellow citizens at the same time that they assumed most people were “true” patriots—ironically, “true” in the sense of conforming to the state’s version of patriotism that many viewed as inauthentic. In fact, when asked what it means to be a patriot in Russia today, respondents often grew visibly uncomfortable and sought to clarify whether I was interested in their own opinion or how it is “for everyone.” The interviews revealed an important distinction between “patriotism” and “being a patriot”: “patriotism” is an individual and authentic ideal, while “being a patriot” concerns loyalty and conformity. “Patriotism” is apolitical and therefore ambivalent about the current regime, while “patriots” unambiguously support the Kremlin. And crucially, individuals assume they are alone in their understanding of patriotism, while they perceive the majority of Russians to be patriots in ways portrayed by the government and media (for summary, see Table 2).

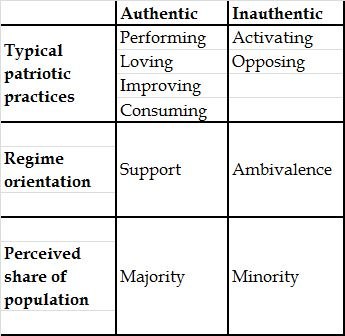

When placed in focus groups, the social impact of “being a patriot” became especially clear in the relationship between politics, patriotism, and authenticity (see Table 3). The kinds of activities considered authentically patriotic include performances, especially those in which fellow citizens are likely to participate—particularly the Victory Day-linked “Immortal Regiment March” phenomenon of recent years. While attempts to activate patriotic sentiment “from above” or to direct patriotic opposition were considered inauthentic, it was not so much the fact that they were imposed as they were focused on the wrong targets. In this sense, “activated patriotism” was still viewed as legitimate and expected in focus groups even if it was misguided. In addition, a cardinal break between interviews and focus groups was observed in terms of regime orientation. Patriotism was expressed in terms of outright support for the government, while ambivalence was described as artificial (and even lazy). Likewise, perceptions of the distribution of majority and minority attitudes reversed in comparison to the interviews.

The Degrading of Relations between Citizens and the State

Taken together, the interviews and focus groups suggest that Russian citizens have distinctive understandings of patriotism that differ significantly from the state’s version as articulated in state patriotic programs. Yet in a social environment, those private differences are subordinated to the public necessities of “being a patriot” or signaling one’s loyalty. Political scientists call this phenomenon “preference falsification” and have demonstrated how such a gap between individually-held and publicly-expressed beliefs tends to maintain the status quo until a change in conditions makes it possible for individuals to openly express their preferences for change, often in a dramatic cascade. One significant consequence of preference falsification in this context is that the state’s information about actual preferences in society degrades over time. To put it bluntly, Russians will confirm that they are patriots as long as they are asked by the state. Hence, despite the clearly individualist aspects of patriotism felt by interview respondents, there is no room for individualism in the state’s version of patriotism. Indeed, there are no pro-regime individualist alternatives available in the mainstream of Russian politics (see Table 4).

Another consequence of preference falsification is likely to be a widening of the gap between individual and public preferences. As the government’s investment in patriotism increases almost unabated, the bureaucratization of patriotism in Russia will attract additional players in business and politics that further dilute its content. Moreover, the increased competition along with diminished state budget resources means that increasingly strict performance indicators are likely to be enforced. Indeed, one already sees a clear shift over time in the goals of state programs: if in 2001 it involved broad notions of changing political culture, the 2016 program designates quantitative targets for the creation of patriotic organizations and popular attendance of mass events. As the bureaucratic politics of “being a patriot” increasingly becomes a public political enterprise, it can only move further from citizens’ understandings of authentic patriotism at the same time that citizens continue openly to express routine support.

Conclusion

The Kremlin’s pursuit of legitimacy by cultivating patriotism is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it benefits from the social dynamics that relate patriotism to loyalty and produce public expressions of regime support despite individual or private dissent. As long as individual Russians assume that most other Russians are patriots, there are few incentives to press for individualist political alternatives or even to challenge regime narratives. In this sense, Russia’s nation of patriots is as an “imagined community” that is continually flagged and reinforced through state institutions and media. On the other hand, the government’s massive investment in patriotism risks a long-term crisis of legitimacy. Individuals may continue to openly accept the regime while holding their grievances close to the vest. As witnessed multiple times in the course of regime upheavals in Eastern Europe and the former USSR since 1989, legitimacy crumbles when those grievances erupt into the open. For many Russians, the government’s version of patriotism barely resembles their own and many perceive it as distressingly close to nationalism. Those concerns may increase over time, particularly as they remain hidden from view. As long as the government’s policy is to maintain and advance public expressions of patriotism while alienating the opposition—and especially the individualist, pro-regime sentiments already present in society—it potentially increases the scale of grievances as well as the scale of future potential crises.

J. Paul Goode is a Senior Lecturer in Russian Politics at the University of Bath.

[PDF]

Figure 1. Budget for State Programs for Patriotic Education, 2001-2020

(millions of rubles)

Table 1. Budget for State Patriotic Programs (millions of rubles)

Table 2. Patriotism and Authenticity in Interviews

Table 3. Patriotism and Authenticity in Focus Groups

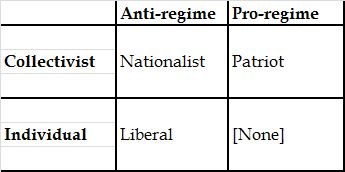

Table 4. Russia’s Ideological Landscape